Blair Kamin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic for the Chicago Tribune, is used to generating controversy with his reviews. Yet the Donald Trump outburst that followed Kamin’s critique of the enormous sign the developer put on his Chicago skyscraper last year beat all the rest, earning the critic a mention on Jon Stewart’s “Daily Show.”

Responding to concerns that the field of architecture criticism is losing influence in the digital age, Kamin explored the state of his profession in a talk at the Society of Architectural Historians conference in Chicago this past spring. Edited excerpts follow:

Critics write the first draft of architectural history, but historians get the last word. Still, I would argue that, in some respects, your job is easier than mine.

After all, the architects and real estate developers I write about are still alive and can react to negative reviews with icy glances, or by hanging up the phone, or, if they happen to be Donald Trump, by mounting Twitter attacks that call me “third-rate,” “a loser,” and claim that I was fired from my job when, in fact, I was on a Nieman fellowship at Harvard. Most of your subjects, on the other hand, are dead. Maybe that’s why I’d really like to trade places with you. Dead architects can’t talk back.

In response to Paul Goldberger’s announcement three years ago that he was leaving The New Yorker, came these apocalyptic stories: “The Architect Critic Is Dead”…. “The Death of Criticism”—a message delivered, no less, by the distinguished critic Witold Rybczynski. This trope about the death of criticism has been proclaimed so often and with such self-righteous certainty that it must, like all conventional wisdom, be subject to rigorous scrutiny.

I suggest we start with Saul Steinberg’s famous New Yorker cover lampooning the parochialism of Manhattan's cosmopolitan classes. In journalism, such pronouncements belong under the pejorative heading: “two facts and a deadline make a trend.” The New Yorker doesn’t have an architecture critic! The New York Times architecture critic rarely writes about architecture! New York is getting short shrift on architecture coverage. Therefore, everywhere else, the architecture critic is dead. This is, plainly, nonsense.

Far more important than this myopic focus on New York is a much broader shift: The rapidly changing media ecosystem. Newspapers—and, by extension, architecture critics—used to have a virtual monopoly on the urban design debate. No more. Not in the age of aggregators, bloggers, tweeters, and snarky real estate websites.

The comment box and social media mean that everybody’s a critic—or, at least, everybody has a digital soapbox from which to shout their opinion. Here I am, on my old blog, delivering my message that architect Bertrand Goldberg’s Prentice Women’s Hospital in Chicago is “boldly sculptural” and “brilliantly engineered”—in short, a landmark worth saving. And here are readers engaged in vigorous dissent: “If the preservationists want to keep the building intact, then they can buy it,” writes one. Another rebuts me with that famous Yiddish put-down: “landmark, schmandmark.”

Clearly, the days of the critic’s hegemony are done. And even some journalists, like those at The Guardian, are celebrating the shift. Their philosophy of “open journalism” proposes that instead of dictating the news to readers, newspapers should ask their readers what they should be writing about.

Not surprisingly, some critics vehemently disagree. As Goldberger says, “crowdsourcing is not the express train to wisdom.” Yet as I know from years of blogging and tweeting, there is often wisdom in the crowd. The people who live in a neighborhood or work in a building often know more about it than the lazy critic who makes only a cursory inspection.

Architecture critics used to have a virtual monopoly on the urban design debate. No more

My take on all this is that architecture criticism is not dead. Those proclaiming criticism’s death are mistaking the dynamic, tumultuous process of creative disruption for permanent dissolution. They fail to recognize that the circumstances of our time offer promise as well as peril.

I would like to address these challenges in an argument with four parts. It will take us back more than 50 years to the birth of modern architecture criticism; review criticism’s fundamental purposes and foundations of authority; discuss four approaches to criticism, and suggest how criticism can be revitalized in the digital age.

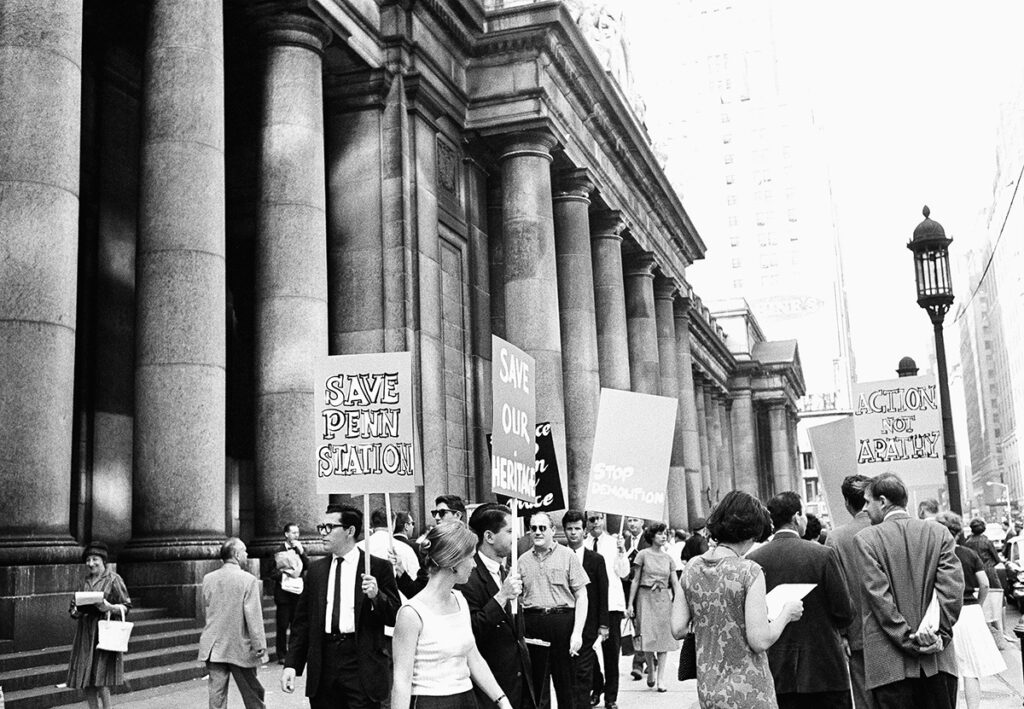

Let's begin with the death of a landmark and the birth of modern architecture criticism. Specifically, let us begin at the blocks of Manhattan, bounded by 7th and 8th avenues, 31st and 33rd streets. You know what happened here from 1963 to 1966: The old Pennsylvania Station, a civic monument of Roman grandeur was replaced by a hopelessly banal office building, a mediocre sports arena, and the most confusing and claustrophobic train station in America.

Pennsylvania Station's exterior was lined with 35-foot-tall columns of pink granite that evoked the majesty of Bernini’s colonnades in St. Peter’s Square. Sculptures of eagles perched over the main portal, suggesting that the builder of the station, the Pennsylvania Railroad, had conquered this new territory in the manner of the Roman emperors of centuries past.

Inside, the visitor experienced a processional sequence of narthex, nave, and crossing that made Pennsylvania Station a virtual temple of transportation. The soaring space of the general waiting room was modeled on the Roman Baths of Caracalla.

The grandeur of the vast iron and glass concourse led Thomas Wolfe to observe that Pennsylvania Station’s immensity was “large enough to hold the sound of time.”

This grandeur must have seemed as permanent as the Pantheon. Yet it lasted just 53 years. By the early 1960s, the Pennsylvania Railroad, desperate for cash, ignored the pleas of protestors like the architect Philip Johnson. The proud eagles came down and a new station went up, leading to the architectural historian Vincent Scully’s immortal observation: Once, “one entered the city like a god. One scuttles in now like a rat.”

Among the other eloquent voices decrying the demolition of Pennsylvania Station was Ada Louise Huxtable, who that very year had been appointed the first full-time architecture critic of The New York Times. Her weapon was her typewriter.

Playing on the notion that America had become an affluent society, she wrote on May 5, 1963: “It’s time we stopped talking about our affluent society. We are an impoverished society. It is a poor society indeed that can’t pay for these amenities; that has no money for anything except expressways to rush people out of our dull and deteriorating cities.”

And then this, in 1968 after sculptures from Penn Station were discovered in the New Jersey Meadowlands: “Tossed into the Secaucus graveyard are about 25 centuries of classical culture and the standards of style, elegance and grandeur that it gave to the dreams and constructions of Western man. That turns the Jersey wasteland into a pretty classy dump.”

Huxtable was not the first American architecture critic of distinction. She followed a trail blazed by such luminaries as Montgomery Schuyler, the founder of Architectural Record, and Lewis Mumford, the brilliant New Yorker architecture critic.

But Huxtable was different. She wrote for a daily newspaper, not a magazine. And her salvos were launched from the most powerful newspaper platform of all—The New York Times. For decades—first in the Times, then in The Wall Street Journal—Huxtable made architecture matter in a way that it did not before her time. Through her insightful observations, her powerful judgments, her refusal to be blinded by ideology, her insistence on design excellence and her cutting putdowns, she became the yardstick by which all other critics would be measured.

And so, if we architecture critics are doing our jobs well, we deliver judgments with biting wit, like the late Allan Temko’s delicious putdown of San Francisco’s Vaillancourt Fountain. It looked, he said, like something “deposited by a concrete dog with square intestines.”

Goldberger’s rip of the hideous Westin Hotel in Times Square was equally good. It was, he wrote, “a developer’s box in drag … it enthralls in the way a gruesome accident does.”

Equally memorable: Huxtable's shot at Marcel Breuer’s misguided plan to stack a steel-and-glass high-rise atop Grand Central Terminal: “Mr. Breuer has done an excellent job with a dubious undertaking," she wrote, "which is like saying it would be great if it weren’t awful.”

You need courage and conviction to deliver judgments like these. Huxtable developed those qualities as an assistant curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art. Later, she spent a year in Italy as a Fulbright fellow, studying the pioneering concrete structures of Pier Luigi Nervi.

She knew her stuff. She didn’t need anybody to steady her hand. She was thus superbly qualified to call a spade a spade, as when she mocked Philip Johnson’s proposed AT&T Building as a postmodern pastiche that borrowed un-persuasively from such disparate sources as a Chippendale highboy dresser and Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel, stretching that Renaissance masterpiece to massive, almost Fascistic scale.

Huxtable had once worked for Johnson at the Museum of Modern Art, but her integrity obligated her to set that relationship aside. She was judging the architecture, not the architect. Which brings us to the heart of the matter: How critics form their judgments.

When I assess a building, I focus on five areas, which are an adaptation and extension of the trio of criteria articulated by the Roman writer Vitruvius: “firmness, commodity and delight.”

First, quality: Does the design elevate prosaic materials to visual poetry, as does the extraordinary brickwork of Henry Hobson Richardson's Sever Hall at Harvard? Or, like Peter Eisenman’s Aronoff Center for Design and Art at the University of Cincinnati, is the building provocatively designed but poorly constructed? The Cincinnati building drew critical raves when it opened. Yet it was so shoddily constructed that, less than 20 years later, it required a complete façade renovation that cost millions.

Second, utility: Does form follow function or does it follow the architect’s ego? Daniel Libeskind’s jaggedly crystalline addition to the Denver Art Museum may be a striking sculptural form, but good luck to the curators hanging paintings on its tilting walls.

Third, continuity: What does the building give to—or take from—its surroundings? Does it engage its neighbors in a bracing dialogue, like Chicago’s 333 West Wacker, which responds so gracefully to its setting at the meeting of the Chicago River’s two branches? Or is it an autonomous object, like the One Superior Place apartment high-rise in Chicago. One Superior Place is one inferior building—a monotonous hulk that looks like it parachuted in from the old East Berlin.

Fourth, humanity: Does the design fuse art and technology to enrich and ennoble human experience? Does the building have a heartbeat? Does it make your heart beat faster? There is no better example than Louis Sullivan’s masterful Carson Pirie Scott & Co. store, where the honeycomb of terra cotta-cladding and the cast-iron foliate ornament at once celebrate and animate the insert columns and beams of the steel frame.

Fifth, build a bridge between the public and the public realm: I strive to bring home to the reader the broader impact and cultural implications of a given building or urban design. What are the stakes, urban and financial? Why should the reader care?

I strive to bring home to the reader the broader impact and cultural implications of a given building or urban design

Last year, when Donald Trump plastered his name in glowing 20-foot-high letters that stretch as long as half a football field, it was essential that the debate be framed not as a matter of taste, but as the marring of a public space—the great quartet of 1920s towers around the Michigan Avenue Bridge. That approach got results. While we are stuck with Trump’s badge of dishonor, Chicago now has a riverfront sign district ordinance that will prevent anything like it from happening in the future.

In my view, it's an act of cosmic justice that, under certain light conditions, the “T” in the “Trump” sign disappears and his name reads instead as "rump."

In the introduction to her fine book “Writing about Architecture,” Alexandra Lange articulates four approaches to architecture criticism: formal, experiential, historical, and activist. Even if these distinctions are somewhat artificial (and perhaps outdated), they're worth examining.

Formal Criticism

The first, formal criticism, was best practiced by Huxtable. In this approach, the primary emphasis is on the visual—the building or the object’s form.

In Huxtable’s case, the voice was so authoritative and the prose so sparkling that the conclusions were like thunderbolts hurled by Zeus.

Experiential Criticism

The second type of criticism, experiential criticism, is anything but Olympian in tone. It focuses instead on how the building makes the critic (and, by extension, the reader) feel:

This type of criticism indulges in free-form cultural associations and makes unlikely connections like the one Times critic Herbert Muschamp drew between the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and Marilyn Monroe: “After my first visit to the building, I went back to the hotel to write notes … I took a break to look out the window and saw a woman standing alone outside a bar across the street. She was wearing a long, white dress with matching white pumps, and she carried a pearlescent handbag. Was her date late? Had she been stood up? … I asked myself, Why can’t a building capture a moment like that? Then I realized that the reason I’d had that thought was that I’d just come from such a building. And that the building I’d just come from was the reincarnation of Marilyn Monroe.”

Self-indulgent? Perhaps. But the critic uses the metaphor of Marilyn Monroe to make vivid his judgment that Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim is a curvaceous, exhibitionist, and utterly unique example of American creativity.

Historical Criticism

A third type of criticism, historical criticism, frames the building in the context of the architect’s career and presence on the world stage. A snippet from Goldberger’s review of Norman Foster’s Hearst Tower, which calls the architect "the Mozart of modernism," gives you a taste of that approach.

Activist Criticism

The fourth type of criticism, activist criticism, was originated at the San Francisco Chronicle by Allan Temko, who like Huxtable, began writing as a newspaper critic in 1963. Temko, a brawler in a bow tie, had a remarkable impact on his city, championing such significant shifts as the demolition of the Embarcadero Freeway, which had cut off downtown San Francisco from the bay.

I loved Temko’s pugnacious approach and adopted it as my own when I became the Chicago Tribune’s architecture critic in 1992. Whenever possible, I have tried to stop hideous buildings before it’s too late—and to introduce constructive alternatives and idea into the public debate.

One example of that approach harks back to the destruction of Pennsylvania Station. Just as New York is haunted by that demolition, so Chicago is haunted by the wrecking of Adler & Sullivan’s Chicago Stock Exchange Building. Well, not everyone in Chicago. The alderman of the Chicago City Council—or, the “alder-creatures,” as Mike Royko once called them, care little or nothing about architecture.

In 1996, they quietly stripped 29 buildings and districts, including the Art Deco Carbide & Carbon Building and Mies van der Rohe’s 860-880 Lake Shore Drive apartments of temporary landmark status. That opened the door to the defacement or demolition of these priceless gems.

Raising the specter of the Stock Exchange, I issued a warning: Does anybody get what Chicago is doing to itself? Is the city about to repeat its sad penchant for self-destruction? That critique helped to spark a public debate. Subsequently, Mayor Richard Daley pushed the City Council to grant permanent landmark status to 28 of the 29 endangered buildings and districts.

That was a great victory. But in retrospect, looking back nearly 20 years, I know that it was really two significant victories: Not only were those buildings protected, but the rules of the historic preservation game in Chicago were essentially rewritten.

With Daley’s backing, Cook County began offering property tax breaks for the owners of certified city landmarks. And in the last 20 years, those tax breaks have joined with the emergence of a newfound appreciation for the past, particularly the boutique hotel trend, to have a widespread impact. The exquisite conversion of Daniel Burnham’s Reliance Building into a hotel is just one example.

But let me bring you back to reality: Such victories are rare. You lose more battles than you win, as I found in my unsuccessful fight to halt the defacement of Chicago’s Soldier Field. Here, the City of Chicago and the Chicago Bears crammed a modern seating bowl inside the old stadium’s historic colonnades. It’s Klingon meets Parthenon. And it doesn’t have enough seats to host a Super Bowl. When the federal government stripped the stadium of its National Historic Landmark status in 2004, the action was a mere consolation prize. What this episode demonstrated, quite painfully, is that activist criticism has the power to set the agenda, but it does not have the power to enact that agenda.

So where does that leave us? Alexandra Lange’s articulation of the four types of criticism is valuable insofar as it goes, but it doesn’t go far enough. It's a recapitulation of criticism in the analogue age, not a blueprint for how criticism should respond to the digital age.

What is fundamentally different about the digital age is this: Interactivity. We interact in new ways with public sculptures like the Crown Fountain in Millennium Park. The faces displayed on its towering LED screens even seemed to anticipate the iPhone.

In the past, newspaper columnists often rhapsodized about having a “conversation with the reader.” But now, that conversation is real. And it calls for critics to adapt: While there is still a need for Olympian pronouncements reached on the basis of scholarship and connoisseurship, the reality of the media ecosystem is that those pronouncements won’t be the last word.

Instead, they’ll be the start of an ongoing conversation, a dialogue that engages the public and, ideally, raises their sights and the sights of those who build and regulate our buildings. Can that make a difference? I think so, as seen by the progression of towers commissioned by the developers of that inferior One Superior Place. After taking critical hits, they did a turnabout and became the patrons of Jeanne Gang's sensuous Aqua Tower and her just-announced Wanda Vista Tower, which could bring a new boldness to the renowned Chicago skyline.

Here, then, are three principles that can revitalize criticism in our time:

- Presence beats absence: Critics need to deliver their message on a multitude of platforms—the newspaper, television, radio, and social media. The old days of expecting the reader to come to you are over. The first job of the critic is to engage the reader and to make architecture and urban design issues a part of the daily conversation.

- Participate in, curate, and convene the conversation: The critique is no longer the last word; it starts the conversation. Comments are content, not just add-ons. Help readers navigate the digital jungle and find the best ideas. Use a series to convene a civic debate, as the photographer John Kim and I did with our series, "Designed in Chicago, Made in China."

- Innovate but adhere to first principles: What a critic writes, what impact he or she has on architectural dialogue is more important than how many clicks he gets or how many followers she attracts. While the means of delivering criticism should change in response to new media realities, the essential purposes of criticism—separating the meritorious from the mediocre, monitoring the shapers of our built world, and illuminating architecture’s powerful effect on human experience—must remain unchanged.

Architecture Criticism: A Constructive Art

Whatever form it takes, architecture criticism matters because it pulls back the curtain on the doings and dealings of the often-secretive world of architects, developers, and politicians. It thus democratizes the inescapable art, inviting readers to be more than passive consumers of the buildings that are handed to them. Rather, it urges them to take a leading role in shaping their surroundings.

The foremost practitioners of this art provoke as well as explain. Their insight can prick the conscience of a city or a nation—and, over the long run, set the stage for dramatic change. These critics raise not just our awareness, but our expectations.

Their best work, like Huxtable’s appraisal of the World Trade Center’s twin towers—“the start of a new skyscraper age or the biggest tombstones in the world”—can even seem prophetic.

Whether it is delivered on the printed page or on a mobile phone, architecture criticism matters because the critic serves as a one-man or one-woman Greek chorus: Standing apart from the play, astutely observing the action, telling us what it all means, articulating truths and the inescapable art that others are unable—or unwilling—to confront.

When criticism fulfills that mandate, it remains vibrant, valued, and very much alive.