Gadhafi was a rogue force on the world stage, denying Libya’s terrorist activities and dismissive of his country’s role in the ghastly Pan Am bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland that killed 270 in 1988. “Something of the past,” he said, bored. The year was 2000 and what really interested him was the emerging power of the internet and how he might use it to reach a U.S. audience.

Gadhafi grinned. “I hope that I will find a forum to talk to the Americans so that I can brainwash them for their own interests.” Before parting, we were asked if we would grant him a direct pipeline to the readers of our newspaper, the Chicago Tribune, through regular postings on our website.

We would not. But it turns out Gadhafi, who in 2011 would meet a vengeful end at the hands of fellow Libyans, was merely anticipating a new era in political communication: easy, unchecked access to American eyes and ears, the tedium of interviews with fact-checking journalists overcome.

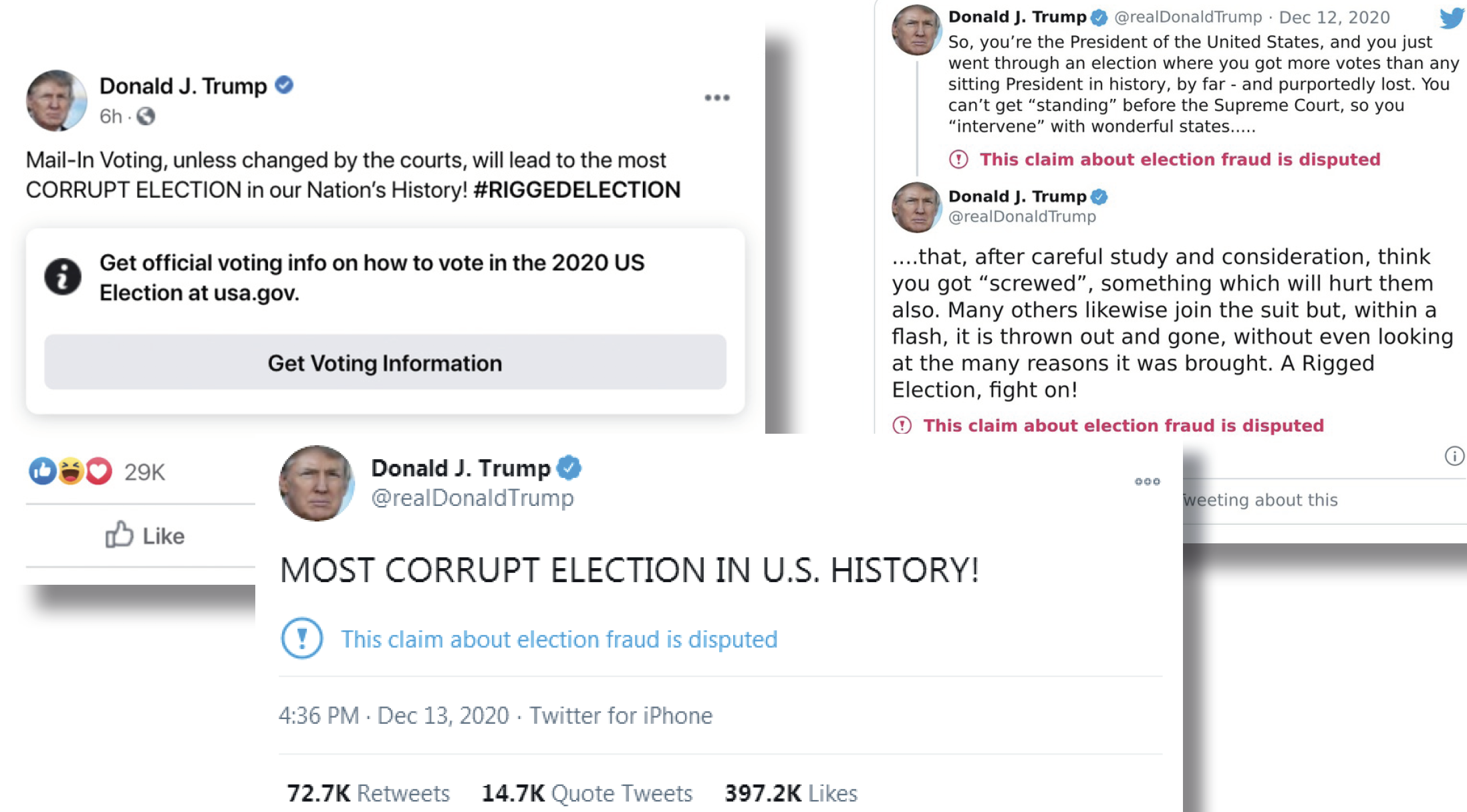

Whatever brainwashing forum he imagined in the U.S., we have likely overperformed. Complicit social media and cable news forces helped Donald Trump ascend to the presidency through near-frictionless use of their platforms. In turn, his prolific use of them has created one of the most deceitful records in American political history, inconclusively footnoted as disputed.

Trump: “MOST CORRUPT ELECTION IN U.S. HISTORY!”

Twitter: “This claim about election fraud is disputed”

When it’s working, journalism — the journalism of verification — has traditions and tools that conclusively right the record. “Never deceive the audience,” Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel state plainly in their essential book, “The Elements of Journalism.” Yes, the industry struggled with this during Trump’s winning campaign and early presidency and we have written extensively about those failings, including in this issue. But earlier stenographic habits have been replaced by a new rhetoric.

“Increasingly detached from reality, President Donald Trump stood before a White House lectern and delivered a 46-minute diatribe against the election results that produced a win for Democrat Joe Biden, unspooling one misstatement after another to back his baseless claim that he really won.”

That is the unflinching lede on the AP news account of a December 2 speech about the “rigged” election that Trump gave from the White House (a speech CNN refused to air, calling it a “propaganda video”). It was as revealing about the coverage changes in mainstream media as the following sentence was about social media as a haven for the president’s disinformation campaigns: “Trump called his address, released Wednesday only on social media and delivered in front of no audience, perhaps ‘the most important speech’ of his presidency.” (Italics mine.)

Over @realDonaldTrump, his more than 88 million followers were offered a two-minute version of the speech, which Twitter labeled “disputed.” On his Facebook page, Trump’s 34 million followers could find the full speech, eventually with a flag reminding us that voter fraud was rare and Biden the projected winner. The AP reported that about an hour after it was posted, the video had been shared by more than 60,000 Facebook users and viewed “hundreds of thousands of times.” A week later, it had been shared by more than 345,000 and viewed 14 million times.

Looking at the platforms’ blue rebukes — so quiet aside the president’s thundering demagoguery — I couldn’t help but think that Trump was living Gadhafi’s dream of the idealized political forum.

Emily Bell, a Columbia University journalism professor and leading voice on technology and news, tweeted a photo of the Facebook post before it had been flagged and called for journalism and academic institutions to return any Facebook funds they’ve received “until the company implemented its own policies.” She added, “If you are taking money from Facebook for any purpose aimed at ‘improving the information ecosystem’ and you are not publicly protesting this farcical situation then you are making matters worse.”

When I messaged her to ask what Facebook and Twitter should do, she argued that due to the Georgia Senate races we remained in an election period and the platforms’ own policies to curb election disinformation should be enforced. She advocated suspending Trump’s Twitter account until the inauguration “given the volume of disinfo on it,” and suspending or removing Trump’s Facebook account. “If they make rules around elections then they should apply them — particularly to the more influential actors.”

Meanwhile, documenting the cascading trail of lies has been left to traditional media and their overworked fact checkers. The Washington Post’s Fact Checker project, now a bulging database of presidential deceptions, catalogued 23,035 false or misleading claims made by Trump between his election and September 11. In August alone, as election season was entering the homestretch, the Post tallied an average of more than 50 falsehoods a day. “It’s only gotten worse — so much so that the Fact Checker team cannot keep up,” they conceded. Noting they were weeks behind in updating the collection — the Post fact-checkers weren’t able to check all those August claims and add them to the database until October — they asked for our forbearance: “We maintain this database mostly in our spare time, in addition to our day jobs.”

The bigger toll, of course, is on the nation, eroded with each spurious claim. And having witnessed President Trump’s social media abuses, only the naive could imagine a disciplined Citizen Trump. Both Facebook and Twitter exempted him from certain sanctions because of his political status, sanctions they could enforce when he leaves office (Twitter has explicitly said that it will) — or not if he declares he is running again.

But focusing on whether his accounts will be suspended or banned is ultimately a distraction, the well of social discourse so poisoned and the polluters so many. Maria Ressa — the courageous Filipino journalist who has been targeted and threatened through Facebook mobs linked to President Rodrigo Duterte and who is now being prosecuted for her journalism — reminds us the problem transcends Trump.

“American technology giants created the platforms that enabled manipulation at a mass scale,” she wrote, “structurally designed to undermine democracies by playing to our worst selves.”

If we don’t demand better, we are all accomplices.

Ann Marie Lipinski is the curator of the Nieman Foundation and the former editor of the Chicago Tribune.