Before the coronavirus pandemic gripped the world, people in Milwaukee had another unprecedented preoccupation: the 2020 Democratic National Convention.

The four-day event—still slated to take place here, though postponed from July to August because of the health crisis — had promised to bring tens of thousands of visitors, economic impact, and a hot white spotlight to this city. That meant new restaurants, public art projects, and hotels rushed to completion, and Airbnbs outfitted for imminent demand.

Not so many weeks ago, before Mayor Tom Barrett held briefings about the health crisis, he loved to talk about how there would be more journalists here during the DNC than in the history of Milwaukee before then.

We wanted to cut through the noise and get to a meaningful and focused exploration of democracy and citizenship

It was that kind of heightened anticipation—and also the deep political polarization that exists in our battleground state — that motivated me and artist-photographer Kevin J. Miyazaki to start working on a project called “This is Milwaukee” about a year ago. We wanted to consider what Milwaukee, one of the most racially and economically segregated cities in the U.S., might contribute to the national conversation at a historic moment for our community.

Our core question was designed to inspire people—our subjects, our audience, and ourselves—to reflect on democracy in a deeply personal way. Among the four questions we pose to all of our subjects is this:

“What is democracy, for you?”

We wanted to cut through the noise, the horse-race journalism, and the firehose of breaking political news out of Washington, and get to a meaningful and focused exploration of democracy and citizenship.

Over the course of many months, Miyazaki and I identified more than 300 people who embody the notion of citizenship, people who contribute to the public life of the city, in ways that might be high-profile or nearly invisible. We narrowed that list to about 100 people to include in the project, including pastors, schoolchildren, philanthropists, teachers, refugee advocates, journalists, restaurant owners, community gardeners, kind neighbors, caregivers and others. We don’t ask people their party affiliation, but we’ve taken pains to ensure as many Milwaukeeans as possible will see and hear something of themselves in our nonpartisan work. That’s meant including people across various forms of difference, including political difference.

Miyazaki makes a black-and-white portrait of each subject, and I conduct an audio interview, asking four questions. In addition to the question about democracy itself, I ask:

“To what extent are you optimistic about the future of the country?”

“What are the qualities you care about in political leaders?”

“What are Milwaukee’s most pressing issues today?”

Before the pandemic hit, some of the interviews took place in Miyazaki’s studio, but many were done in people’s homes or places of business, where we sought out small, quiet rooms where I could get good audio. Miyazaki fashioned a homemade photo booth from PVC pipe, a piece of black velvet and a light. The whole kit can be set up in about five minutes.

The interviews have been intense and, at times, surprisingly tender.

Howard Leu, a marketing strategist and the very first subject selected for “This is Milwaukee,” came to the U.S. when he was 5 years old, settling with his family in a small town in Alabama with about 15 Asian residents. His father opened a Chinese restaurant there and died before he could truly enjoy the fruits of his labor. This was the context for how Leu, who had just sworn the oath to become an U.S. citizen, answered our question about democracy.

Kevin J. Miyazaki

“In my own identity, I often thought about where should I live and where should I pursue my dreams,” Leu said, haltingly. “I think about my father, and I think about [how] this was his dream, and for me to fulfill his dream of becoming American … I think that is democracy for me.”

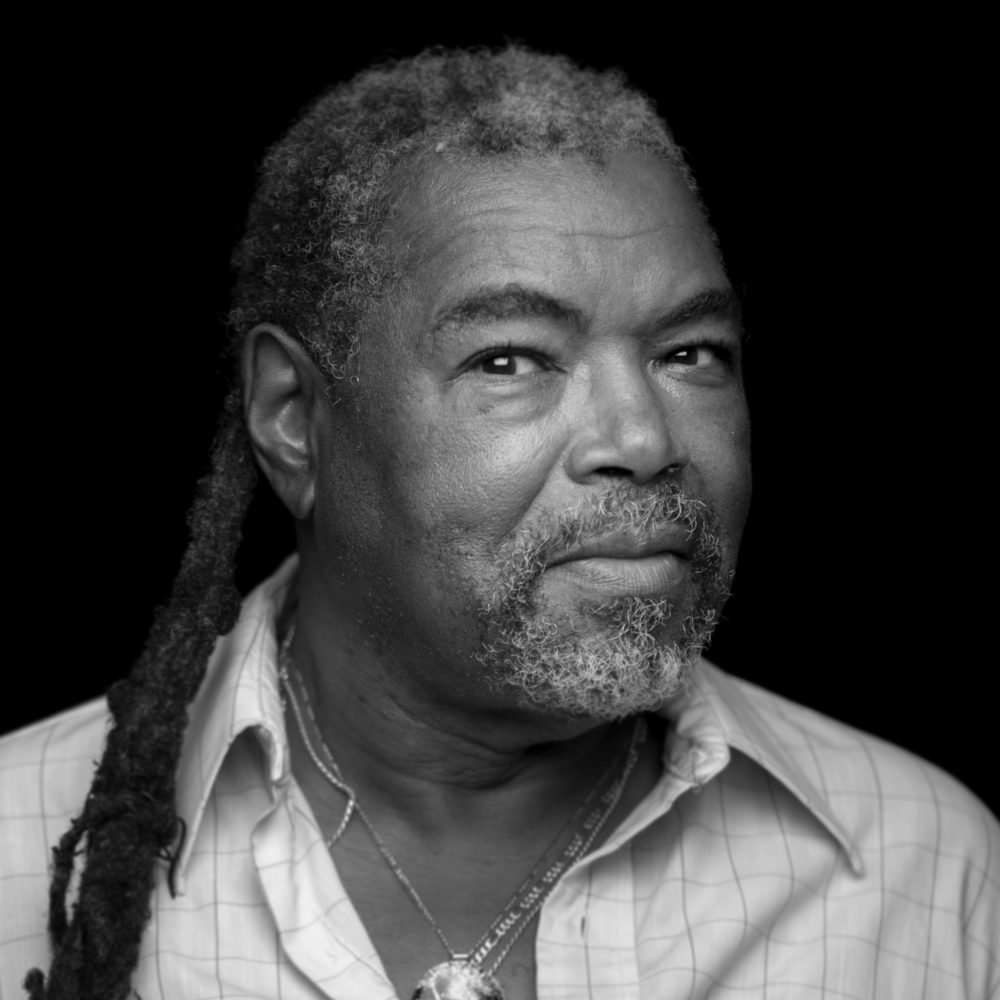

The day we visited Willie Weaver-Bey at his home in the Metcalfe Park neighborhood on Milwaukee’s north side, his garage had just been broken into and his lawnmower stolen. He assumed neighborhood kids had taken it. It’s the kind of thing that happens on his block, he told us. Part of doing good for his neighbors, especially young people, involves radical empathy and forgiveness, he said.

“I get real emotional about seeing people suffer because there’s no reason for suffering in a country that’s supposed to be the home of the brave and the land of the free,” said Weaver-Bey, an artist, veteran, and community leader who first picked up his paint brushes while spending 40 years in a federal prison on drug charges. “We’re supposed to be the greatest country in the world and yet we don’t act like it. We’ve got so many have-nots, because the haves are so greedy.”

Indeed, many of our subjects spoke about democracy in terms of its fragility. Dominique Samari, who co-founded P3 Development Group, which helps organizations build environments of equity and inclusion, wondered aloud about this: “Has there been a thin veneer over this entire thing for as long as I know and it’s just now starting to crack? Has it ever been what I thought it was? Has this idea of democracy ever existed in the way that we thought it did, or have we just now gotten to the point where we’re starting to see through the cracks?”

One of our earliest goals was to reclaim space online, where people were overwhelmed and politically manipulated even before Covid-19. Now that so many of us are huddled together online, finding connection but also confusion and stress, we hope our project might be an antidote to—or at least a respite from—the web’s worst, anti-democratic tendencies.

As the worldwide Covid-19 crisis took hold, we wondered if we shouldn’t set our project aside. Would people really want to talk about democracy while worrying about a deadly virus? Would the nearly 100 interviews we had gathered, which we had planned to unfurl in the weeks leading up to the DNC, sound ancient, from some faraway, pre-Covid era?

By mid-March, about 10 days before Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers issued his safer-at-home order, as most Americans were still adjusting to a rapidly altering reality, we noticed something. Our interviews started running long. That meant our subjects, many of whom hold wildly divergent political beliefs, sometimes met as appointments spilled into each other. An LGBTQ-interested philanthropist bumped elbows with a pro-life activist. People shared worries and hand sanitizer at a kitchen counter in Miyazaki’s studio.

And people had a lot to say.

“You and I are sitting here on a day in which it feels that America is being canceled,” said Charlie Sykes, a longtime conservative talk radio host in Milwaukee who founded The Bulwark news network in 2018 and is an NBC/MSNBC contributor. “What we are facing now is a crisis of citizenship because ultimately all of the problems we have come back to—are Americans willing to be responsible for their role in a democracy?”

“This is Milwaukee” has been a return to the core values of journalism — deep listening, shoe-leather reporting, and thoughtfulness about how our community is represented

Joey Zocher, who founded a public charter school on Milwaukee’s south side, anticipated in March what is more evident now—that the pandemic exacerbates the kinds of longstanding inequities that exist in Milwaukee. More than half of the known deaths from Covid-19 in Milwaukee County have been among black residents, according to the county medical examiner, while African Americans make up about 28% of the population here.

“This current situation we’re going through with this viral panic attack is a perfect time for people who don’t understand what it’s like living in trauma to just take a snapshot of how they feel right now,” said Zocher, who talked about the privilege of being white and the challenge of being queer in Milwaukee during her interview. “Imagine that’s how most of our students feel day to day, and [it’s] even scarier [for them] because they actually know family members who have been shot randomly, and they actually know violence. They know brutality. Their chances of dying are significantly higher than most people who are in a sheer panic right now.”

Even a 10-year-old girl, with a love of rivers and animals, understood the stakes. She cried when I asked her about democracy, took a moment to gather herself, and insisted on continuing when I told her we could stop the interview.

“I feel like we could make the United States a great country,” said a tearful Mimi Zippel, who is in the fifth grade at Highland Community School and who was nominated to our project by her art teacher for being a good listener and caring about her classmates. “But I also am scared of what could happen, of what they’re doing about illnesses and urgent matters like the coronavirus.”

During those March interviews, we quickly realized that the conversations we were provoking at the start of this project, which felt meaningful in a time of coarse political discourse, felt more urgent. We were witnessing answers to those questions as citizenship plays out in Milwaukee’s response to Covid-19, as the world grows more local and collaborative.

Kevin J. Miyazaki

At the suggestion of Adam Carr, a journalist, historian, and community organizer who is both a subject and adviser to “This is Milwaukee,” we started holding “This is Milwaukee Talking” gatherings via Zoom, featuring three subjects from our project and anyone who wants to listen in. Camille Mays, one of the primary participants in our first conversation, sounded her Nepalese singing bowl, almost by accident, as we waited for that gathering to start. It was an artifact of a recent tragedy in her life, which she shared with the group. After years of working to comfort families and attending funerals for victims of violence, Mays lost her 21-year-old son. He was fatally shot in November. We agreed that we’d start each “This is Milwaukee Talking” get together with Mays and that healing call to attention. The virtual events are informal by design — we make no introductions, for instance — but focused. We revisit questions about citizenship and see what surfaces, a discussion of beloved local businesses, perhaps, or ideas about public space and how people will gather in a post Covid-19 world.

By the time we were officially sheltering in place, many of our plans—including an exhibit at City Hall scheduled for June and the distribution of a newspaper-like publication—were uncertain. The ways we had planned to share our findings and content were largely dependent on public gatherings. One thing we decided we could do, though, is simply amplify the work of the people in our project in the meantime. So, we’re doing some modest, ongoing reporting, checking in with our subjects, and sharing information via our platforms, small as they may be.

When Cree Myles, an Instagrammer who goes by “Black Emily Dickinson,” co-wrote an op-ed for Teen Vogue in the wake of the April 7 primary election, which controversially went forward in spite of the risk of coronavirus exposure, we shared that. We let our Instagram and Facebook followers know, too, that Sister MacCanon Brown’s homeless sanctuary in Milwaukee’s Amani neighborhood, a primary source of food for many, was in need of canned goods and other supplies.

We’ve had to discontinue in-person interviews, but we’ve started experimenting with delivering our audio recorder to people’s doorsteps and then interviewing them via Skype or FaceTime. We may also mail the recorder to subjects, one at a time, to keep the project moving. We’re also adding more people to our ever-growing database of potential subjects, including health care workers and those who worked the polls during the primary election.

“This is Milwaukee” has been a return to the core values of journalism — deep listening, shoe-leather reporting, and thoughtfulness about how our community is represented. It’s a slow, independent, noncommercial, and open-ended project that involves more risk and experimentation than most newsrooms could tolerate these days, especially as regional media struggle to survive, furlough journalists, and focus principally on lifesaving, breaking news.

As proud as I am of my career as a newspaper journalist, this project has been powerful and of use to my community in unexpected ways. The experience has led me to wonder — in this time of media disruption and pandemic — what forms of journalism could be incubated from small, agile experiments like ours.