It took a terrorist attack for Google to enter the news business.

On September 11, 2001, after hijackers crashed two commercial jets into the World Trade Center as well as a third plane into the Pentagon and another into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, Internet users turned to the search engine for information. Again and again, they typed in terms like “New York Twin Towers,” but found nothing about what had happened that morning. Google’s Web crawlers hadn’t indexed “Twin Towers” since the month before, which meant every result that Google returned was, given the context, totally and painfully irrelevant.

Google quickly set up a special page for “News and information about attacks in U.S.,” with links to the websites of about four dozen newspapers and news networks, along with links to relief funds, resources, and phone numbers for airlines and hospitals. A link to this makeshift news page stayed there for weeks, just below the search bar on Google’s minimalist homepage. Within a year, Google had incorporated a news filter into its search algorithm so that timely headlines appeared atop a list of search results for relevant keywords.

A new era of personalized news products began, in earnest, as a reaction to horrific global news.

Today, a Google search for news runs through the same algorithmic filtration system as any other Google search: A person’s individual search history, geographic location, and other demographic information affects what Google shows you. Exactly how your search results differ from any other person’s is a mystery, however. Not even the computer scientists who developed the algorithm could precisely reverse engineer it, given the fact that the same result can be achieved through numerous paths, and that ranking factors—deciding which results show up first—are constantly changing, as are the algorithms themselves.

We now get our news in real time, on-demand, tailored to our interests, across multiple platforms, without knowing just how much is actually personalized. It was technology companies like Google and Facebook, not traditional newsrooms, that made it so. But news organizations are increasingly betting that offering personalized content can help them draw audiences to their sites—and keep them coming back.

A new era of personalized news products began, in earnest, as a reaction to horrific global news

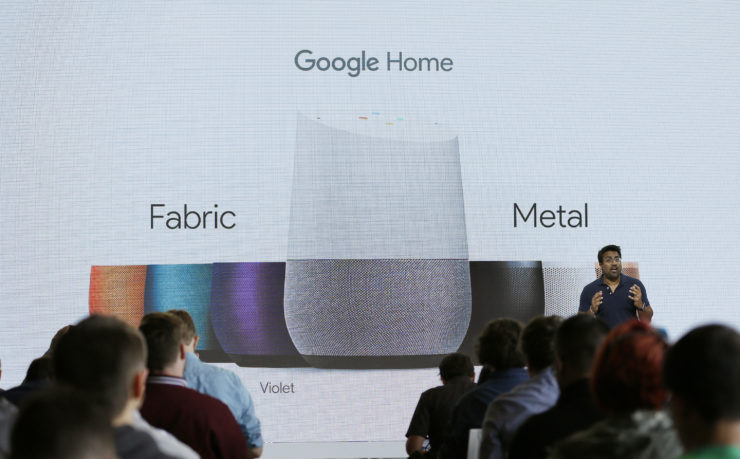

Personalization extends beyond how and where news organizations meet their readers. Already, smartphone users can subscribe to push notifications for the specific coverage areas that interest them. On Facebook, users can decide—to some extent—which organizations’ stories they would like to appear in their news feeds. At the same time, devices and platforms that use machine-learning to get to know their users will increasingly play a role in shaping ultra-personalized news products. Meanwhile, voice-activated artificially intelligent devices, such as Google Home and Amazon Echo, are poised to redefine the relationship between news consumers and the news.

While news personalization can help people manage information overload by making individuals’ news diets unique, it also threatens to incite filter bubbles and, in turn, bias. This “creates a bit of an echo chamber,” says Judith Donath, author of “The Social Machine: Designs for Living Online” and a researcher affiliated with Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. “You get news that is designed to be palatable to you. It feeds into people’s appetite of expecting the news to be entertaining … [and] the desire to have news that’s reinforcing your beliefs, as opposed to teaching you about what’s happening in the world and helping you predict the future better.”

As data-tracking becomes more sophisticated, voice recognition software advances, and tech companies leverage personalization for profit, personalization will only become more acute. This is potentially alarming given the growth of websites—news-oriented and otherwise—inhabiting the political extremes, which on Facebook are easy to mistake for valid sources of news. When users can customize their news, and customize to these political and social extremes, civic discourse can suffer. “What’s important is how people use the news to have a discussion,” says Donath. “You may have friends or colleagues, and you read the same things in common. You may decide different things about it. Then you debate with those people. If you’re not even seeing the same news story, it leaves you with a much narrower set of people with whom you share that common ground. You’re losing the common ground of news.”

Information-filtering algorithms, whether those of tech giants or news organizations, are the foundation of personalization efforts. But journalists and technologists approach this info-filtering environment in fundamentally different ways. News organizations share information that is true and hopefully engaging. Technology companies like Google and Facebook enable the sharing of information that is engaging and hopefully true. Emerging technologies will only exacerbate the existing problems with algorithmically promoted junk information.

Still, algorithms have a place in responsible journalism. “An algorithm actually is the modern editorial tool,” says Tamar Charney, managing editor of NPR One, the organization’s customizable mobile listening app. A handcrafted hub for audio content from both local and national programs as well as podcasts from sources other than NPR, NPR One employs an algorithm to help populate users’ streams with content that is likely to interest them. But Charney assures there’s still a human hand involved: “The whole editorial vision of NPR One was to take the best of what humans do and take the best of what algorithms do and marry them together.”

In an “Inside NPR” blog post about the editorial ethics driving NPR One’s personalization (co-written by Charney, chief digital officer Thomas Hjelm, and senior VP of news and editorial director Michael Oreskes), the so-called “secret sauce” behind the app is “an editorially responsible algorithm.” Metrics track listener behavior so that, over time, the app can offer content catered to individual preferences. Charney declined to describe exactly what data the NPR One app collects—“We’re a little proprietary,” she says—but she gave some examples of how the algorithm personalizes NPR content.

For instance, NPR One knows when you stop listening, which in the future can help producers decide how to keep listeners interested. It can also tell which listeners heard a story that later had a correction appended to it, and deliver that correction to the top of those listeners’ queues. In at least one case, when a correction was significant, NPR One’s algorithm determined who had heard the original segment. NPR then emailed the correction to that list of users.

NPR One can apply that same principle to multi-part stories. If a listener misses the first or second part of a story, the app will be sure to offer the missing part to that listener, something those who listen to NPR on the radio often might miss. “Nobody thinks that’s what personalization algorithms are for,” Charney says. “But we can counter both the filter bubble and we can counter false narratives this way.”

Important news stories—both local and national—are presented to all users, with no options for personalization; the app will always provide the lead story of the day and other important stories selected by editors. So while NPR One enables listeners to choose the “non-essential” stories that are more particular to one’s interests—music reviews, for example, or stories about sports or interviews with artists—and decide on the level of depth they hear on certain topics, dialing up or down the frequency of updates, human editors still ultimately decide what you need to hear.

“You may not be interested in Syria. We’ll tell you if this big thing happened and you need to know about it, but we’ll spare you from the incremental news,” Charney says. “The ability to skim across some stories and to dive into other stories, that may be the power of personalization.”

We now get our news in real time, on-demand, tailored to our interests, across multiple platforms

The skimming and diving Charney describes sounds almost exactly like how Apple and Google approach their distributed-content platforms. With Apple News, users can decide which outlets and topics they are most interested in seeing, with Siri offering suggestions as the algorithm gets better at understanding your preferences. Siri now has help from Safari. The personal assistant can now detect browser history and suggest news items based on what someone’s been looking at—for example, if someone is searching Safari for Reykjavík-related travel information, they will then see Iceland-related news on Apple News. But the For You view of Apple News isn’t 100 percent customizable, as it still spotlights top stories of the day, and trending stories that are popular with other users, alongside those curated just for you.

Similarly, with Google’s latest update to Google News, readers can scan fixed headlines, customize sidebars on the page to their core interests and location—and, of course, search. The latest redesign of Google News makes it look newsier than ever, and adds to many of the personalization features Google first introduced in 2010. There’s also a place where you can pre-program your own interests into the algorithm.

Google says this isn’t an attempt to supplant news organizations, nor is it inspired by them. The design is rather an embodiment of Google’s original ethos, product manager for Google News Anand Paka says: “Just due to the deluge of information, users do want ways to control information overload. In other words, why should I read the news that I don’t care about?”

That is a question news organizations continue to grapple with. If reactions to The New York Times’s efforts to tailor news consumption to individual subscribers are any indication, some people do want all the news that’s fit to print—and aren’t sold on the idea of news personalization.

The Times has recently introduced, or plans to do so later this year, a number of customization features on its homepage involving the placement of various newsletters and editorial features—like California Today, the Morning Briefing, and The Daily podcast—that depend on whether a person has signed up for those services as well as readers being able to choose prioritized placement of preferred topics or writers. Soon, the biggest news headlines may still dominate the top of the homepage, but much of the surrounding content will be customized to cater to individuals’ interests and habits.

The Times’ algorithm, drawing from data like geolocation, will make many of these choices for people. A person reading the news from, say, India might see news relevant to the Indian subcontinent in a more prominent place online than a person reading from New York City. The site already features a “Recommended for You” box, listing articles that you haven’t yet read, also including those suggestions in emails to some subscribers.

Then-public editor Liz Spayd discussed the changes in a March column, noting that she’d heard from several readers unhappy with the newspaper’s efforts to offer a more unique reader experience, and to document and share subscribers’ activity with them. “I pay for a subscription for a reason: the judgment and experience of the editors and writers that make this paper great. Don’t try to be Facebook … Be The New York Times and do it right,” commented one reader.

“Don’t try to be Facebook” was a common refrain among the commenters. The social network has had its fair share of issues with news curation in its attempts to become “the best personalized newspaper in the world,” as CEO Mark Zuckerberg put it back in 2013. To say nothing of the fake news that proliferates on users’ news feeds, the “trending topics” section had a very rough few months in 2016. First, news “curators” were accused of bias for burying conservative news stories; then, Facebook laid off the entire editorial staff responsible for writing descriptions of items appearing in the section, with some disastrous results, such as when a made-up story—claiming Megyn Kelly was fired from Fox News for being a supporter of Hillary Clinton—showed up at the top of the “trending” list. The story appeared on the blog USPostman.com, a website registered to an address in Macedonia, known for its robust network of information scammers, PolitiFact reported at the time. In January of this year, Facebook gave up on personalized trending topics altogether, filtering topics by users’ geographic regions rather than interests.

Even more troubling than Facebook’s trending topics woes was the revelation in September that the social network had sold upwards of 3,000 ads—totaling at least $100,000—to a Russian firm connected to the spread of pro-Kremlin propaganda and fake news. The firm, posing as Americans in a myriad of groups and pages, sought to target U.S. voters during the presidential campaign and, while most of the ads didn’t specifically reference the election or any candidates, they “appeared to focus on amplifying divisive social and political messages across the ideological spectrum,” wrote Alex Stamos, Facebook’s chief security officer, in a blog post. The fact that the topics of the ads were so wide-ranging—varying from immigration and gun rights to the LGBT community and Black Lives Matter—is suggestive of how damaging personalization can be and how it isn’t confined to any particular party line. Soon after, Twitter announced it had found and suspended at least 200 accounts linked to Russian operatives, many of whom were identified as the same ad buyers active on Facebook.

Meanwhile, in May, Google briefly tested a personalized search filter that would dip into its trove of data about users with personal Google and Gmail accounts and include results exclusively from their emails, photos, calendar items, and other personal data related to their query. The “personal” tab was supposedly “just an experiment,” a Google spokesperson said, and the option was temporarily removed, but seems to have rolled back out for many users as of August.

Now, Google, in seeking to settle a class-action lawsuit alleging that scanning emails to offer targeted ads amounts to illegal wiretapping, is promising that for the next three years it won’t use the content of its users emails to serve up targeted ads in Gmail. The move, which will go into effect at an unspecified date, doesn’t mean users won’t see ads, however. Google will continue to collect data from users’ search histories, YouTube and Chrome browsing habits, and other activity.

“The ability to skim across some stories and to dive into other stories, that may be the power of personalization.”

—Tamar Charney, managing editor of NPR One

The fear that personalization will encourage filter bubbles by narrowing the selection of stories is a valid one, especially considering that the average internet user or news consumer might not even be aware of such efforts. Elia Powers, an assistant professor of journalism and news media at Towson University in Maryland, studied the awareness of news personalization among students after he noticed those in his own classes didn’t seem to realize the extent to which Facebook and Google customized users’ results. “My sense is that they didn’t really understand… the role that people that were curating the algorithms [had], how influential that was. And they also didn’t understand that they could play a pretty active role on Facebook in telling Facebook what kinds of news they want them to show and how to prioritize [content] on Google,” he says.

The results of Powers’ study, which was published in Digital Journalism in February, showed that the majority of students had no idea that algorithms were filtering the news content they saw on Facebook and Google. When asked if Facebook shows every news item, posted by organizations or people, in a users’ newsfeed, only 24 percent of those surveyed were aware that Facebook prioritizes certain posts and hides others. Similarly, only a quarter of respondents said Google search results would be different for two different people entering the same search terms at the same time.

This, of course, has implications beyond the classroom, says Powers: “People as news consumers need to be aware of what decisions are being made [for them], before they even open their news sites, by algorithms and the people behind them, and also be able to understand how they can counter the effects or maybe even turn off personalization or make tweaks to their feeds or their news sites so they take a more active role in actually seeing what they want to see in their feeds.”

On Google and Facebook, the algorithm that determines what you see is invisible. With voice-activated assistants, the algorithm suddenly has a persona. “We are being trained to have a relationship with the AI,” says Amy Webb, founder of the Future Today Institute and an adjunct professor at New York University Stern School of Business. “This is so much more catastrophically horrible for news organizations than the internet. At least with the internet, I have options. The voice ecosystem is not built that way. It’s being built so I just get the information I need in a pleasing way.”

Webb argues that voice is the next big threat for journalism, but one that presents news organizations with the opportunity to play an even greater role in people’s everyday lives. Soon, we likely will be able to engage with voice-activated assistants such as Siri and Alexa beyond just asking for the day’s news. We’ll be able to interrupt and ask questions—not just in order to put things in context and deepen our understanding of current events, but to personalize them. To ask, “Why should this matter to me?” or even, “What’s the most important news story of today—for me?”

Today, you can ask the Amazon Echo to read you the news—a bit like the way radio broadcasters simply read straight from the newspaper when radio was in its infancy. But technologists, journalists, and scholars believe that in the near future, artificially intelligent voice-activated devices will offer a genuinely interactive and personalized news experience. “Maybe I want to have a conversation with The Atlantic and not USA Today, so I’m willing to pay for that,” Webb says. “This has to do with technology but also organizational management because suddenly there are like 20 different job titles that need to exist that don’t.”

The Echo’s Flash Briefing comes with preloaded default channels—such as NPR, BBC, and the Associated Press—already enabled, but it’s “very much on the consumer to decide” what they want to hear from the Echo, says Amazon spokeswoman Rachel Hass. Any web developer can include a site in the Flash Briefing category the Echo dips into for the news, but being selected as a default outlet by Amazon gives news organizations a huge competitive advantage. Research shows that most people don’t change default settings on their phones, computers, and software—either because they don’t want to, or more likely, they don’t know how to.

Much like a search engine, Amazon isn’t focused on differentiating material from various sources or fact-checking the information the Echo provides. The Echo does, however, read a quick line of attribution during news briefings. “As Alexa reads out your Flash Briefing, she attributes each headline or news piece by saying ‘From NPR’ or ‘From the Daily Show,’” Hass explains. There’s also tremendous incentive for news organizations to play nice with Amazon as a way to get cemented into the device’s default news settings—a relationship that evokes the damaging dependency newsrooms have on Facebook for traffic.

Because Flash Briefings aren’t limited to traditional news outlets, you could conceivably find briefings available from all kinds of sources—including full-fledged newsrooms and individuals. Even former Vice President Joe Biden now delivers daily news briefings, introducing various news articles of his choosing, which are available on Google Home as well as the Echo.

“There are already more than 3,500 Alexa Flash Briefing” skills, the term Amazon uses for the app-like command-driven programs created by developers to use on the Echo. For example, there’s the skill Trump Golf, which offers updates on President Trump’s golf outings whenever prompted by the command, “Alexa, ask Trump Golf for an update.”

“I suspect these devices are the most important thing to emerge since the advent of the iPhone in 2007,” says Kinsey Wilson, former editor for innovation and strategy at The New York Times, “because they open up spaces—principally in the home and in the car—where it allows for a higher, more informal degree of interaction.”

In some ways, voice seems like a natural extension of search. Devices like the Amazon Echo and Google Home will enable people to dip into search engines without having to type. More than that, though, these new devices are meant to be conversational. “It’s not so much asking them a bunch of questions but having a collaborative exploration of some topic,” says Alex Rudnicky, computer science professor at Carnegie Mellon University. “This idea of, ‘Wouldn’t it be really nice if you could call up a friend of yours who is very knowledgeable and just have a conversation with them?’”

The personalization element isn’t just the heightened sense of camaraderie one might feel with a conversational robot versus a stack of broadsheets or a talking head on cable television. Personalization is rooted in the fact that devices like the Echo actively learn about the human user with every new interaction and adjust their behavior accordingly. This is the same personalization technique used by Google and Facebook—slurp up myriad individual data, then tailor services to suit—but it uses devices that are always listening—and therefore always learning.

Media organizations that want to create conversational news products for voice-activated devices will have to figure out how to produce and package entirely new kinds of stories, perhaps including advanced tagging systems for snippets of those stories, and be sure their methods integrate with the operating systems these devices use. “The existing SEO methods that we have might need to be rethought completely from scratch,” says Trushar Barot, a member of the digital development team at BBC World Service. “There may be new methods that emerge that are native to voice recognition.”

Personalized voice assistants face potential obstacles. Sounding too much like a machine is one problem; sounding too much like a human is another. “It’s very easy for people, psychologically, to start anthropomorphizing the device into a real entity and developing genuine human feelings about it,” says Barot. “Plus, the fact that it’s a device that’s in their home and it’s learning more and more about their lives and potentially becoming much more intelligent about proactively offering you suggestions or ideas. That brings up challenging ethical issues.”

News organizations’ use of voice interfaces raise a host of ethical concerns related to data collection, privacy, and security. We don’t know precisely what data these devices collect about individuals (few people read company privacy policies) but, if smartphones have taught us anything, the rough answer is: Everything they possibly can. And there’s not an easy answer to who, exactly, owns this data, but one thing’s for sure—it’s not (just) you. This data has immense value, not just to those generating, capturing, and analyzing it, but to a wide range of companies, tech giants and otherwise.

So what do newsrooms do with audience data? “There are potentially ways for newsrooms to use that personalization [data] in a useful way,” says the Berkman Klein Center’s Donath. It largely depends “on what you think the mission of the newsroom is. Is it to inform people as well as to possibly to have its own model of what’s important information that people should be aware of? Or is it much more of an entertainment model?” If the latter, that audience data is incredibly valuable for organizations to make sure they’re creating and distributing the type of content people want each day.

In the near future, artificially intelligent voice-activated devices will offer a genuinely interactive and personalized news experience

Amazon is considering offering developers raw transcripts of what people say to the Echo, according to a July report in The Information. Newsrooms will have to grapple with whether it’s ethical to use data from those transcripts as a way to make money, a move that would certainly enrage some privacy-minded consumers. For publishers, that could be an important revenue stream, but it could also creep audiences out and lessen trust, not enhance it.

What happens to a person’s perception of information, for instance, if the same voice some day is reading headlines from both Breitbart and The Washington Post? “What does that do to your level of trust in that content?” Barot asks. Plus, “there is a lot of evidence that people inherently trust or believe content or news or information shared by their friends. So if this is a similar type of dynamic that’s developing, what does that do for newsrooms?”

Loss of a sense of sources is a big issue, according to Donath: “What’s useful is knowing where something comes from. Depending on what your perspective is, it can cause you to believe it more or believe it less. When you see everything in this generic feed, you have no idea if it’s being reported by something right-leaning or left-leaning. In a lot of ways, the entire significance of what you’re reading is missing.”

These concerns certainly aren’t unique to voice technology. There’s reason to worry that personalization will only exacerbate existing trust issues around news organizations given the gaping partisan disparity found in a September 2017 Gallup survey on Americans’ trust in mass media. Though Democrats’ trust and confidence in the media has actually jumped to the highest level it’s been in the past two decades, from 51 percent in 2016 to 72 percent this year, the opposite can be said for Republicans: only 14 percent of Republicans have a great or fair deal of trust in the mass media, which ties with 2016 as a record low in Gallup’s polling history.

Although some newspaper readers might like being greeted by name each time a major news organization sends a daily roundup of stories, news organizations run the risk of sounding inauthentic, the way campaign emails from politicians seem impersonal despite their attempts to the contrary.

According to Powers, news organizations should share with audiences that the content they’re seeing may not be the same as what their neighbor is seeing—and how they can opt out of personalization. “There needs to be more transparency about what data they’re actually collecting, and how people can manually turn [personalization efforts] on or off or affect what they see,” says Powers.

Perhaps most importantly, it’s essential for news organizations to remember that they can’t leave personalization up to algorithms alone; doing so will likely only narrow people’s news consumption rather than expand it, and could lead to the spread of misinformation. “You still need to have an actual human editor looking to make sure that what’s popular isn’t bogus or hurtful,” says Powers.

Personalization should be a way to enhance news decisions made by human editors, professionals committed to quality journalism as a crucial component of an open society. The news-filtering algorithms made by companies that refuse to admit they are even in the media business—let alone in a position to do great harm—aren’t bound to even the most basic journalistic standards. And yet they are the dominant forces filtering the world around us in real time.

With reporting by Eryn Carlson