For many mornings on my way into the Chicago Tribune newsroom, I passed by an Arthur Miller quote engraved in the lobby: "A good newspaper, I suppose, is a nation talking to itself."

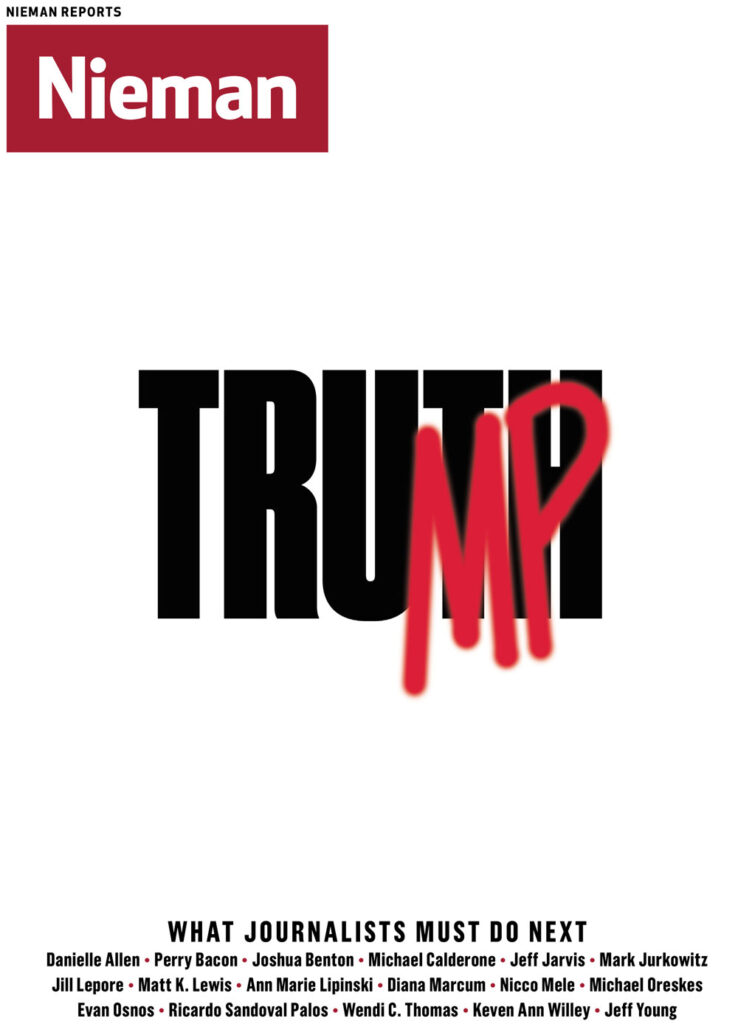

That sentiment, as sturdy as the travertine marble into which it was carved, now seems a comic irony. We are, in all our media, a nation screaming past each other. Miller's genteel aspiration proved an antique this campaign cycle and nothing about our post-election world has corrected for that. President-elect Donald Trump, not satisfied to have won the election, continues his work as social media provoker-in-chief, energizing his followers and baiting a wounded press corps.

The smart essays we have commissioned and collected here reflect on this historic campaign for the White House and point the way forward for journalism. Some of the paths are provocative: Historian and New Yorker writer Jill Lepore, having sounded the alarm bell on polling a year ago, has seen enough and argues it's time to regulate the publication of pre-election polls. One urges journalists to borrow from Trump's success: Harvard political theorist and Washington Post contributor Danielle Allen calls for storytelling that acknowledges our transition from a reading to a watching culture.

The weeks since the election have underscored the urgency for new approaches. As frightening as the proliferation of "fake news" (an oxymoron for the post-truth age) is the specter of some journalists spreading known lies. That's fake news too. After Trump stormed Twitter with bogus claims about millions voting illegally, we woke to this headline leading the CNN homepage: “I won the popular vote.” A tepid qualifier was tucked beneath a photo of the president-elect giving the thumbs up: "Without evidence, Trump claims fraud cost him popular vote." It is painful to see the good work of journalists like Brian Stelter, whose media criticism for CNN was among the most responsible of the election, effectively mocked by his own newsroom.

Prevaricating politicians are not new. What did I.F. Stone say? "All governments lie." Stone mined for stories in government records and archives, didn't care about access, and never pulled a punch to protect it. Journalists jockeying for stories and status at a dissembling White House, rather than out in the agencies and beyond, will be the least effective in covering this administration. What a spectacle to see the biggest names in television news parading into an off-the-record meeting-turned-scolding with Trump two weeks after the election. The New York Times got it right, insisting their meeting with Trump was on-the-record, reported in real time, and followed with a complete transcript.

The lessons of Joseph McCarthy's destructive legacy are also instructive. Nieman Reports and Louis M. Lyons, the legendary curator of the Nieman Foundation, advocated for "interpretative reporting" to overtake the stenography that characterized much coverage of McCarthy. And it was journalist Edward R. Murrow plainly speaking truth to power that helped bring a stop to the Wisconsin senator's reckless accusations of treason.

Still, these waters feel uncharted. "The news media," James Fallows wrote, "are not built for someone like this." The ease with which a tweeted untruth can dominate a news cycle and hijack newsrooms for days is new in presidential politics. It comes at a time when lightning is the only acceptable speed for posting a candidate's utterances, let alone a president's.

But we can apply news judgment in that moment between tweet and retweet rather than serve as accomplices to destructive claims. How different the vote fraud coverage could have been had more journalists seen that the news lay in the fact that the president-elect lied. As Nieman's Lyons once said in the wake of McCarthy, "Who but a newspaperman can show you the record?"

With no evidence that the rhetoric has turned from campaign to presidential, journalism must cope quickly. Soon enough, @realDonaldTrump will be @POTUS.

The majestic Tribune Tower, home to the Chicago Tribune for almost a century, recently was sold and the newsroom will move to make way for new development. Much of the building is landmarked and protected, but not the lobby with the engraved Arthur Miller quote, the fourth-floor newsroom with its inscription of the First Amendment, or this from Flannery O'Connor: “The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.”

Across the street from the Tribune, the barge-shaped building that long housed the Chicago Sun-Times on the banks of the Chicago River was demolished over a decade ago. In journalism's place, a developer built a 98-story skyscraper and affixed his name in stainless steel letters, 20-feet tall: TRUMP.