This article is based on the author's book, "Democracy's Detectives: The Economics of Investigative Journalism," being published in October 2016 by Harvard University Press.

The path to The Washington Post’s 1999 Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation into shootings by D.C. police started with something that wasn’t there. A Post database specialist noticed that a FBI homicide report provided no data on justifiable homicides by police.

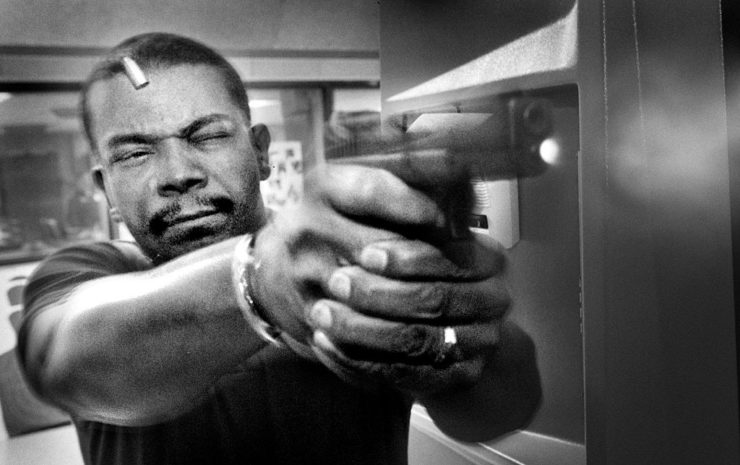

Reporters went after the data, producing a five-part “Deadly Force” series that precipitated major changes in the D.C. police department that saved lives. It also earned the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. The Post’s reporting revealed that D.C. police shot and killed more individuals per resident than police officers in other large U.S. cities, and that a surge in shootings by police coincided with the hiring of many new officers and the introduction of the Glock 9mm in the D.C. police force. My cost-benefit analysis of this project shows that the results of reporting do not come cheaply to news organizations but deliver tremendous value to society.

In the absence of a single, accurate, and authoritative source for police shootings, The Washington Post assembled the data using many documents, including court records, use-of-force reports, and financial settlements. The reporting group, known internally as “Teamcop,” worked on the series for approximately eight months. At least nine people contributed to the series, including three reporters, two editors, several researchers, a database specialist, and a computer-assisted reporting expert. Guided by the Post’s pay scale, I estimate that the series cost the paper $487,000 (in 2013 dollars, which I used in all my calculations) to report.

Policy changes were swift. D.C. police Chief Charles Ramsey tightened policies on when officers could fire at unarmed people in automobiles, increased use-of-force training for officers by 100,000 training hours, and improved the tracking of information on police shootings. The drop in fatalities was similarly quick. In 1998, D.C. police shot 32 people, resulting in 12 deaths. In 1999, the year following the Post series, shootings dropped to 11, with four fatalities. The next year fatal shootings by police dropped to one.

If the first year of the new police policy resulted in eight deaths averted, how can you value this? To value small decreases in risks spread across populations, economists look at what you must pay workers to accept higher risks of death in their jobs. In federal rulemakings, regulators assign a figure of $9.2 million to a “statistical life saved,” which is the monetary value of the reduction in risk across the D.C. population of being shot by police.

Eight statistical lives saved, at $9.2 million per statistical life, amounts to $73.6 million, a figure that leaves out many other benefits of fewer police killings, such as reduced medical and emotional costs. The police spent some $4.195 million on additional use-of-force training, which leaves $69.4 million in net policy benefits. Divide that by the story’s cost of reporting ($487,000), and the bargain for society becomes clear: For each dollar the Post invested in reporting, society gained over $140 in net policy benefits in the first year.

There is no market mechanism that transforms impacts such as the value of lives saved by accountability journalism into equivalent subscription or advertising revenue. Yet assessing the impact of journalism is an important task in these days of cash-strapped newsrooms. While accountability reporting can cost media outlets thousands of dollars, it generates millions in net benefits to society by changing public policy. When “Deadly Force” won a Pulitzer, Post executive editor Leonard Downie Jr. noted it was “a classic case of journalism that matters. Its thorough, air-tight reporting, powerful writing and compelling presentation alerted our readers to an important human rights problem in their own city.” The problem then, which remains today, is how to fund similarly expensive stories whose reporting costs are concentrated on news organizations yet whose benefits are widely distributed across society. The greater availability of data may make accountability reporting itself more accountable, as interested observers can follow the causal chain that links new reporting to new policies and outcomes.

The path to The Washington Post’s 1999 Pulitzer Prize-winning investigation into shootings by D.C. police started with something that wasn’t there. A Post database specialist noticed that a FBI homicide report provided no data on justifiable homicides by police.

Reporters went after the data, producing a five-part “Deadly Force” series that precipitated major changes in the D.C. police department that saved lives. It also earned the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. The Post’s reporting revealed that D.C. police shot and killed more individuals per resident than police officers in other large U.S. cities, and that a surge in shootings by police coincided with the hiring of many new officers and the introduction of the Glock 9mm in the D.C. police force. My cost-benefit analysis of this project shows that the results of reporting do not come cheaply to news organizations but deliver tremendous value to society.

In the absence of a single, accurate, and authoritative source for police shootings, The Washington Post assembled the data using many documents, including court records, use-of-force reports, and financial settlements. The reporting group, known internally as “Teamcop,” worked on the series for approximately eight months. At least nine people contributed to the series, including three reporters, two editors, several researchers, a database specialist, and a computer-assisted reporting expert. Guided by the Post’s pay scale, I estimate that the series cost the paper $487,000 (in 2013 dollars, which I used in all my calculations) to report.

Policy changes were swift. D.C. police Chief Charles Ramsey tightened policies on when officers could fire at unarmed people in automobiles, increased use-of-force training for officers by 100,000 training hours, and improved the tracking of information on police shootings. The drop in fatalities was similarly quick. In 1998, D.C. police shot 32 people, resulting in 12 deaths. In 1999, the year following the Post series, shootings dropped to 11, with four fatalities. The next year fatal shootings by police dropped to one.

If the first year of the new police policy resulted in eight deaths averted, how can you value this? To value small decreases in risks spread across populations, economists look at what you must pay workers to accept higher risks of death in their jobs. In federal rulemakings, regulators assign a figure of $9.2 million to a “statistical life saved,” which is the monetary value of the reduction in risk across the D.C. population of being shot by police.

Eight statistical lives saved, at $9.2 million per statistical life, amounts to $73.6 million, a figure that leaves out many other benefits of fewer police killings, such as reduced medical and emotional costs. The police spent some $4.195 million on additional use-of-force training, which leaves $69.4 million in net policy benefits. Divide that by the story’s cost of reporting ($487,000), and the bargain for society becomes clear: For each dollar the Post invested in reporting, society gained over $140 in net policy benefits in the first year.

There is no market mechanism that transforms impacts such as the value of lives saved by accountability journalism into equivalent subscription or advertising revenue. Yet assessing the impact of journalism is an important task in these days of cash-strapped newsrooms. While accountability reporting can cost media outlets thousands of dollars, it generates millions in net benefits to society by changing public policy. When “Deadly Force” won a Pulitzer, Post executive editor Leonard Downie Jr. noted it was “a classic case of journalism that matters. Its thorough, air-tight reporting, powerful writing and compelling presentation alerted our readers to an important human rights problem in their own city.” The problem then, which remains today, is how to fund similarly expensive stories whose reporting costs are concentrated on news organizations yet whose benefits are widely distributed across society. The greater availability of data may make accountability reporting itself more accountable, as interested observers can follow the causal chain that links new reporting to new policies and outcomes.