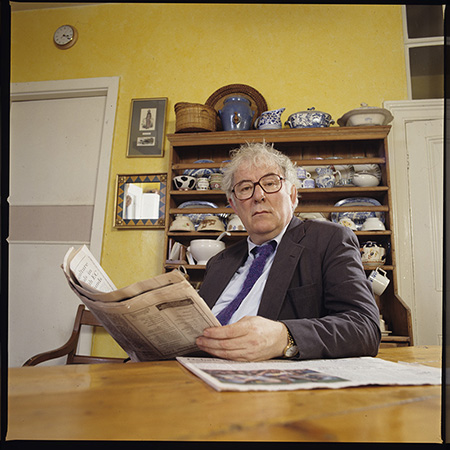

Seamus Heaney at home in Dublin, 1996. Photo by Bobbie Hanvey/Bobbie Hanvey Photographic Archives, John J. Burns Library, Boston College

After his mother died in 1984, Seamus Heaney found solace in “Kaddish,” Allen Ginsberg’s poetic outpouring after his own mother’s death, but he could not follow Ginsberg’s example. If his sense of loss was to enter his poetry, he had to listen for his muse, not direct it.

“I’m afraid of the will and the intention taking away from the subconscious supply,” he said.

Later Heaney started a poem about a tree that had been cut down. When he reached some lines about the empty space the tree had left, he realized he was writing about his mother. His poetry depended on this sense of surprise and power of accident.

Heaney, a Nobel laureate, died on Aug. 30 in Dublin at the age of 74, leaving an empty space himself. All Ireland mourned the stilling of his voice.

Heaney’s death reminded me of the pleasure of listening to him during my Nieman Fellowship at Harvard in 1984-85. A visiting teacher since 1979, he had recently been appointed Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory, and he taught one semester each year. His modern poetry survey was my favorite among the many courses I took during that year.

One night, after a seminar at the Lippmann House, Heaney went out to dinner with my wife and me and Phil and Donna Hilts. Phil was a Nieman classmate. He and I sat next to each other in the front row of Heaney’s poetry class. He had learned somehow that Heaney liked octopus cooked in its own ink and found a Portuguese restaurant in Cambridge that served it. The five of us ate and drank and talked into the night.

The troubles in Northern Ireland were much in the news then. Heaney had earned a reputation as a poet who spoke the truth and championed justice. I had read and liked his early books even though his words and sounds often challenged my ear. The poems were full of beauty, currency and courage.

I first saw Heaney on a bright winter’s morning in class at Harvard Hall. His thick white sideburns extended below his earlobes, and a thatch of fine yellow-gray hair covered his head. His nervous habit of sticking his hands into his tweed jacket had curled and creased the pocket flaps. A brown belt pulled a notch tighter than it once had been held up his black thin-wale corduroy trousers. His tan shoes were scuffed.

Heaney was there to teach, and he worked hard at it. Harvard absorbed him so fully that he wrote almost no poetry while teaching there. “The great pressure of the word ‘Harvard’ makes you feel that you have to be more than yourself,” he said.

In his course, modernity began in 1800 because of William Wordsworth’s promise to upset readers’ expectations by abandoning the conventions of his day in favor of experiment. “We will not enter the poems and feel comfortable within them,” Heaney paraphrased Wordsworth.

He had compassion for the poets he taught and a keen understanding of their work. Each had his or her hour: Gerard Manley Hopkins, Philip Larkin, William Carlos Williams, Elizabeth Bishop, Ted Hughes, Sylvia Plath and more. Heaney devoted two hours to William Butler Yeats, the poet with whom he was most often compared.

About poetry’s source Heaney seemed cautious, as though identifying it might somehow disturb his muse. When he came to the question during his first lecture, he bugged his brown eyes and emitted a guttural sound. Poetry, he said, comes from the impulse to elaborate such speechless moments in sonic terms. It is a mode of shaping intuition or apprehension in a body of language, a transmission, a sensation, in which form, sound and meaning are joined as one.

“When it’s achieved,” he said, “there ’tis—something time-stopping for both poet and reader.”

He found firmer ground in defining how not to be poet. Writing poems is not a matter of coming up with a message, then devising a style, nor is it selling a program through an act of persuasion. Heaney liked Horace’s dictum that poetry should be beautiful and useful but had qualms about the second adjective. “Not the corkscrew and the tin-opener,” he said with a grin, “but what’s inside!”

He was similarly clear about his own vocation. The son of a farmer and cattle dealer, he had announced the aims of his art in “Digging,” a 1966 poem that begins with a startling image: “Between my finger and my thumb / the squat pen rests; snug as a gun.” He admired how his father and grandfather handled a spade, but farming wasn’t for him. “Between my finger and my thumb / the squat pen rests,” he wrote again in the last stanza. “I’ll dig with it.”

After a trip to the United States, it occurred to him that while Ireland lacked the wide-open spaces that nourished the American myth, it did have its bogs. He teased about the difference between “a country with depth but no direction and one with direction but no depth.”

The poem that came from this comparison was “Bogland.” It begins with what Ireland lacks:

We have no prairies

To slice a big sun at evening—

Everywhere the eye concedes to

Encroaching horizon.

And it ends with this picture of the prospects for Irish pioneers:

They’ll never dig coal here,

Only the waterlogged trunks

Of great firs, soft as pulp.

Our pioneers keep striking

Inwards and downwards,

Every layer they strip

Seems camped on before.

The bogholes might be Atlantic seepage.

The wet centre is bottomless.

“I just wanted to take possession of my country,” Heaney said of his early work. And he meant all of Ireland, not just the northern section partitioned off in 1922. In his quest he discovered that poems could tell what happened. They could be “stained glass crying ‘Behold me!’” but they could also be “window glass with a view to what’s outside.” During the most prolific stretches of his career, when the flow was greatest, politics often entered his poems.

By 1985, when I met him, he was already a celebrity in Ireland—“one of theirs,” he said. “You become a representative of what one little place is capable of.” This, of course, meant living up to a reputation, but he understood and accepted this. He had a gift, and he cultivated it.

Heaney was a good-natured man, open and unpretentious, with a zest for life. His surprise in writing poems became his readers’ surprise in reading them. This was magical at times but not magic. The work ethic that made it so applies to any human pursuit: Keep digging.

Mike Pride, NF '85, is editor emeritus of the Concord Monitor. His latest book is "Our War: Days and Events in the Fight for the Union." He blogs at our-war.com