The Signal and the Noise

One tweeter boasted of a "game-changing victory" for crowdsourcing in the early hours of the Boston area manhunt. But what began as a low-grade fever on social media spiked with the wrongful naming of a bombing suspect. All the while, Nieman Visiting Fellow Hong Qu was testing his new tool Keepr as a screen for credibility and posting early results on Nieman Reports as the story unfolded. Qu and journalist Seth Mnookin, who tweeted live from the manhunt, write about how smartphones and their unprecedented power to publish require new journalistic tools and practices, while other Nieman Fellows consider the intersection of social media and journalism in the aftermath of the attac

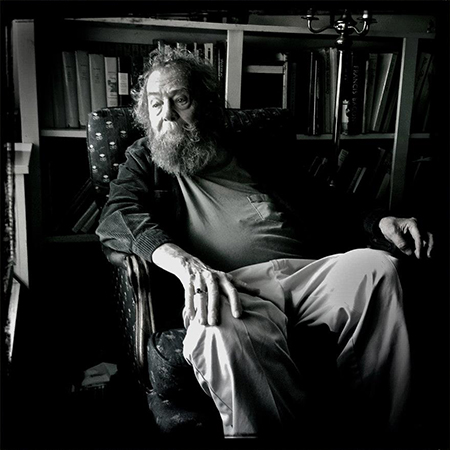

Donald Hall. Photo by Finbarr O'Reilly

Donald Hall, former U.S. poet laureate, has lived at Eagle Pond Farm, with its white clapboard farmhouse and weathered barn, in Wilmot, New Hampshire, since 1975. Hall grew up in the Connecticut suburbs but spent his summers at the farm haying, milking and doing other chores with his grandfather. I got to know Don in 1978 after moving to New Hampshire, when I read “String Too Short To Be Saved,” his memoir of his summers here. The rural life has long been his muse. I started inviting Don to visit the paper I edited, the Concord (N.H.) Monitor, to talk to staff about poetry and place and journalism. Don has written poetry, essays, criticism, plays, short stories, a novel. You name it, he’s done it, including journalism. He’s written for Sports Illustrated, the Ford Times, Yankee Magazine, and many, many others. I now come up here about once a month, and Don and I go over to a place we call Blackwater Bill’s to eat hot dogs. Don likes his hot dogs with the spicy mustard, and relish, and onions. We sat down at Eagle Pond to talk about Don’s work and the writer’s craft. Edited excerpts follow.—Mike Pride, NF ’85

An edited version of this interview appeared in print. Video of their conversation is also available.

MIKE PRIDE: Why don't we talk a little bit about your newspaper reading habit since we do have some newspaper people in our audience? Do you still read the paper regularly?

DONALD HALL: Yeah, I read two newspapers almost all my life. The New Haven Register and the New Haven General Courier. The Courier was the morning paper, the small poor one. The Register was the big one. I moved here and there. I moved to Ann Arbor where I was a teacher at the University of Michigan. I read The Ann Arbor News which was not very good. I added The Detroit Free Press to it, so I read two papers a day. Then I came up here, and it is The Concord Monitor, which is the local paper which you may know rather well, and The Boston Globe. My Grandpere got The Boston Post. Was that a Democratic paper?

I don't know.

He was the only Democrat in New Hampshire, so I thought the Post must be Democratic. There we would hear the results of the Red Sox two days after it happened. [laughs] It would arrive at the post office, The Boston Post. I came back, and it was The Globe and The Monitor. I should say I read The Economist also. The Economist is a Time Magazine that happens to be good. I have a friend in Venezuela. I read about Chavez when he dies but not much anymore. It has diminished like all papers. There's a part of me that doesn't seem like the rest of me that wants to know what's happening everywhere. The Economist fills me in on the rest of the universe. I get the local and simple local news from my newspapers.

You don't use the Internet at all?

I don't have a computer. I'm probably the last person on Route 4 not to have a computer. I know one other guy in New Hampshire that doesn't have one. I'm terrible with my hands, with gadgets, with remembering what to do. I've more or less mastered the ability to change channels on a television, but it takes a lot of intellectual concentration. I'm not high minded or principled, I think, to refuse one, whatever word processors and so on. I welcomed one for my assistant to use.

I was a typist for many years, but not two fingered, one fingered. Well, I could get somebody to type for me. I got an accurate copy. Then when it could be a computer, when I made a new draft, I didn't have to look and see that new mistakes hadn't occurred when my typist copied it over and you could just change it day by day.

If anything I had intensified my desire, my capability, to revise. If I want to change one comma on a page, my assistant with a computer can do it rather quickly I understand.

I know that you have been an incredible letter writer over the years. Now you do use email, kind of second hand email, for a lot of your correspondence.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Well, I came to it because I was driving everybody nuts. I was demanding everybody put names and addresses on envelopes and put in stamps and so on. There were people that didn't want to do the mechanics of it. They were used to emailing everybody. I had a … what's it called that I had?

Fax machine, right?

Yeah. I had a fax machine, and everybody I was faxing turned out to be keeping their fax machine only because of me. That was the quickest I had. Everything has to be quick now. Mostly in New Hampshire, a letter will get there the next day, but nobody wants to use letters. I still write a lot of letters and get away with it. Many people, I think I don't admit that I can get email through my assistant. It's not particularly quick for me, because I see it the day after it gets to her. But that's OK. I've learned to be tolerant.

I do, I worry about the general speeding up of words in the world. I worry about the intelligent young people, students, for whom reading is too slow. All they want is a bit of information. They can get that very easily from Google. Certainly they can get entertainment through games, television, television on the Internet, everything. Everything can be quick and sudden, delayed, or finished quickly.

Someone writing a letter, especially like my mother and my grandmother writing one longhand … my grandmother here had three daughters, and I believe that she wrote them at least a postcard every day. I know my mother wrote her mother about every day.

The post office was three quarters of a mile down the road. Somebody had to go there every day, possibly on a horse. When I was here, I'd go on a bicycle usually and pick it up, because there were always three postcards at least there from the three daughters for their mother.

Kate would sit in a corner of the kitchen in a rocking chair underneath a little cage where she always had a canary who was always called Christopher. She would sit there and read through and pick up her penny postcard or two cent postcard or three cent postcard and write an answer.

I grew up in that house. In my house in Connecticut, both my mother and father wrote letters. The main thing they did was to sit opposite each other quietly, each reading a book. I thought all grownups did that all the time. The life was much slower, of course. This is an 80-year-old man talking now. I'm not saying anything original...

Well, you know, when I was an editor, I would tell my staff to try to write for the newspaper as though they were writing a letter to a intelligent friend. I'm not even sure that if I said that today to a newspaper staff, they would be able to understand the analogy or the comparison.

A letter? What's that? [laughs]

Mike Pride, left, with Donald Hall at Eagle Pond Farm in New Hampshire. Photo by John Soares

You know, for many years, you and I drove together down to the Lippmann House and spoke with the Nieman Fellows. We would tell them beforehand that we were going to tell them what a poet could teach journalists about writing. So I think we ought to talk a little bit about that today. Why don't we start with one of our favorite subjects which is the dead metaphor?

Oh yes.

Let me say first that I remember the first time this came up in a conversation.

So do I. [laughter]

It was with The Monitor staff, and we were sitting in the living room of a friend, actually a colleague, from The Monitor in Concord. You grabbed the newspaper to show people an example of a dead metaphor. You held up that day's editorial, and you pointed out the verb "trigger" and said, "This is a dead metaphor. This is exactly what I mean." It's a word, doesn't have to be a verb, but it's a word that no longer calls up any sort of comparison with the original object. It happens a lot in fast writing. It's a lesson that we tried to teach our journalists to think just a little more about the words they use and to get the dead metaphors out of their work. Would you teach us that lesson?

Absolutely. All winter I read in The Globe and probably in The Monitor about a "blanket of snow." [laughs] Isn't that wonderful? It always annoys me, of course. I hope I'm tolerant. There are words which are used in the headlines because they are short—"Hub fans bid kid adieu." But dead metaphors are something I notice all the time. I criticized trigger because I'm very used to doing it with poems. You can kid yourself so easily. I have written a draft of a poem 50 times, 60 times, and see a gross dead metaphor in it. It's easy enough to do it.

I remember telling a girl over at Cornell one time that I never say "dart" for a person moving quickly because dart is English invented in pubs. A dart is an arrow and using that as a verb … it's like, "I was anchored to the spot" or "I was glued to the spot" means that a ship in a harbor and Elmer's glue are the same thing. Remember that, and maybe it will help you avoid a dead metaphor.

You know, I was just reading the wonderful second volume by Hilary Mantel. Do you remember the title? "Wolf Hall."

Right.

Carrying my usual baggage, and she's a hell of a good writer, novelist, there was, I believe, a "blanket of snow" in one sentence.

We can all do it.

I do it to other poets mostly. Yesterday, I had a letter from a poet whom I had criticized for saying shrouded as a dead metaphor. "The valley was shrouded in mist" or whatever. She wrote me that she did it because the "ou" repeated an "ou" in another word and the d was in another word. I said, "OK, it's still a dead metaphor."

From a practical standpoint, what you're really talking about is helping writers, whatever they happen to be writing, pick the more precise word. Right?

It is precise, because it's not some under the surface, another object. It's looking straightforward. There are people who say that everything in language is originally a metaphor, and I don't understand the thought, but I don't deny it. I remember telling Galloway, "I would rather say 'move quickly' than say 'dart,'" and Galloway said, "Yes, move in the manner of a live person rather than in the manner of a dead person, the quick and the dead." But I forgive myself that one, because I think that the use of the word quick meaning alive as opposed to dead is only used legally as "the quick and the dead."

Quick and the dead, right.

I was amused that he picked that one up so fast. [laughs] With a prose or whatever that is full of dead metaphors, no character can get through. Everything has, as in common in dead metaphors, a veil. Everything has a veil between the utterance of the speaker and the perception of the reader, the listener. Somehow plainness is more intimate than the word "shrouded" the word "blanketed" as we mostly use. A shroud is a shroud, and that's fine. A blanket is a blanket. I can write about it, but don't confuse it with an item which covers. You know? Just don't make it that, which could be shrouded or blanket.

Why don't we talk a little bit about sound? I know that in your poems often sound is a really driving force. I wonder to what extent that you think that is applicable to prose and specifically to prose in news writing, the way you write sentences. Thinking about sound as you write, how do you do that?

I think sound has been for me, and not for everybody, the doorway into poetry, and by sound I particularly mean the repetition of long vowels more than anything else. It's always repetition, and repetition sometimes has a slight difference. It usually dips on A, then you can have one with E. You know? For me, it is a kind of inwardness. In lots of ways I hear...well, I always say that I read not with my eyes and I hear not with my ears with poetry. I hear and see through my mouth, the mouth itself.

Then a reaction to the sounds, it's kind of dreamy and intimate. It opens up, dead metaphor, the ally way to the insides. This I particularly apply to poetry, and I think it is the chief difference. In poetry, we have the line break to organize the rhythm and sometimes to give emphasis.

If there's an an adjective and noun, the noun gets hit harder in the first word of the line. The last word of the line gets emphasis. Not too many people notice that the first word does too. I'm writing prose now rather than poetry, and I'm still listening. A lot of my revision has to do with something sort of obvious.

Mix up long and short sentences. Mix up complex and compound and simple sentences. That's easy. It's easy to say. It is a matter of rhythm of the dance. There is something bodily about the rhythm of a paragraph, and there is a rhythm within a paragraph.

Oh, someone like John McPhee can write four pages without knitting a paragraph because he is so terrific on transitions, but he is quite apt to have a four page paragraph and then a one line paragraph. That could be wonderful. Newspapers can do that too, but most newspaper men do not have time to write 42 drafts of every piece.

The structure of a news story is a kind of form itself. The new news and the background afterwards and so on. I use this, as any frequent newspaper reader must, as a way of skimming. I can read the first part, but I know what happened before so I can listen.

I would say that an editorial writer is sort of freer to be wild and metaphoric than a news writer. The news writer, you know, the Jack Webb thing, "nothing but the facts, ma'am." It has to feel like that, but there can still be adjustment in rhythm and the type of sentence to engage the aspects of the reader which do not have to do only with fact but with some bodily joy and pleasure. That can be done.

Do you test your poems by reading them out loud? Or your prose, do you read your prose out loud?

I have tried that years ago, but it doesn't work for me. I get too distracted by the sound of my own voice. When I'm reading to a bunch of people, I don't listen to my own voice. I try to read my poem off the faces of the people in front of me. I can be saying the poem and saying it using more musical … I'm not acting my poems. I'm singing them if anything. But I can do that while I'm thinking of the next poem I'm going to read too.

Right.

When I was a teacher I always read the poems I was talking about. I realized eventually that I was trying to plant a voice in their head that they could read poems by, a voice that was alert to the music in it and that could help to contribute to that. Some of my old students—of course, by now they're mostly retired, my students—they remember the voice and say that they've kept it. When I'm reading myself prose and poetry, I'm constantly aware of the sound of it, but it's not vocalized because it's not distracting. I hear it. It doesn't seem in my head. It seems I hear it in my throat. [laughs]

So when you say that you hear and see with your mouth, how does that manifest itself? Does your mouth move while you're writing sometimes? How does that …

I'll tell you, if I've read a long time something … Well, like I did Jane, that is complex syntactically, I get very weary in the throat and I realize why, yeah. When I began to be a big reader, everybody would say the same thing, I thought speed was it. I've read a book in just two days today and it was 1,000 pages. Hell, man, you have to learn how to slow down. But if you try to read the Boston Globe that way, you'll just spend the whole day reading one issue. You have to have different degrees of speed and slowness or hearing and feeling in the mouth organs. I said different degrees all the time, different within kinds of prose and so on.

In most newspaper writing, just the obvious, I guess, I hear the editorials more and I know who wrote them sometimes. In the Monitor, I could tell Ralph—

Ralph Jimenez, a regular editorial page writer.

I could not tell you in a million years how I know it's Ralph, I don't think, but I can hear the voice. In a news story, I almost shouldn't hear the voice, it would feel too twisted. I don't know.

There are some writers that I recognize by the way they write the stories, but that's probably because I've been an editor for so long. You recently stopped writing poetry. Would you talk a little bit about why and how that happened?

It happened gradually and I didn't know it was happening. But very few of my poems or a few little parts of them began to feel dense with a kind of excitement of language itself that came by the density of sound and metaphor together. Also unrelated, the poems started to come the way they used to and they used to come in little meteor showers. I would begin three or four poems in two or three days. They'd come to me, I'd be sitting or I'd be driving and I'd pull over to the side of the road and write something down.

Then it might not happen for six months, but I had four or five new poems to work on. Rarely, but occasionally, they would turn out to be the same poem. But they felt different, so that stopped, the meteor showers stopped coming.

I knew a lot about poetry and I had been working in it for years. I pushed, I didn't know how to stop. But I began, gradually, to realize that there was less and less of the old [laughs] like a pitcher with stuff on the fastball that I had when I was younger. Nothing would come out, even like "Kearsarge."

"Kearsarge" is sort of a poem without an idea in it, but with a lot of shape and form and pleasure, I think. I felt it going very gradually. So every now and then, one would resemble the old ones and so on.

But in 2008, I began the last two poems I wrote and I worked on them a couple of years. But I knew, by that point, pretty certainly that this was the end of it. It had gone slowly. I had done it for 60 years, what am I complaining about?

But at the same time, I would publish prose books for 50 years and I began to substitute prose for poetry which is what I do … Oh, when I published a piece in The New Yorker called "Out the Window," I talked about getting old and I talked about not writing poetry anymore.

Of course, The New Yorker published and many people wrote me and said, "It is poetry." OK, it was decorative, it's pretty, that's good metaphors and it's a good sound in it.

If you call something poetry to praise it, that's fine, but it's not a poem, it's something else again. It works by the paragraph, within the paragraph by types of sentences, not so much by moments of assonance and so on. But certainly by rhythm. God, rhythm is utterly important to prose.

I read whole books of prose which are intelligent and full of fact and so on and never does the author ever seem interested in writing anything that's beautiful or that's balanced or rhythmic. It's hard for me to finish those books, intelligent and forming as they may be.

But without beautiful writing.

Yeah. When I was young I was writing poems all the time. I would write a book review for The New York Times, and I think I would often write it in three drafts. Well, when I wrote "String Too Short to Be Saved," which was the first book 50 years ago or so, first prose book, it took me quite a while to write the first chapter. Because everything I wrote sounded like an academic lecture or a book review and I had to find another way to write.

I finally did and by the end of the book, I was pretty much writing three drafts. I was quicker then than I am now, but for God's sake, I'm 85 years old, why shouldn't I slow down.

To get an effect as good, it's different, but forgive me if I call them both good. "A String Too Short to Be Saved," something I'm writing now, is likely to take me up to 50 drafts to do it. But I don't complain at all, because I love doing it. I love the writing, but I love the rewriting too. In fact, rewriting is much more fun than writing and that was always true with poems or everything, because the first draft always has so much wrong with it. That's one reason why I admire a good newspaper. I cannot imagine being able to do it steadily, completely and finished. If I had been one, I probably could have learned how to do it, but it's very distant now from the way I've worked.

I want to talk more about the prose that you're writing now and I do think that there are some ways in which the way you do it would be interesting for a journalist to hear. But I also want to go back to something that we talked about a little earlier today and that is—after Jane died, you told me today and I hadn't really thought about this so much before—that instead of trying to not imitate her voice in your own poems, you basically collaborated with the spirit of her writing in producing some of the poems that you wrote after her death. Could you talk a little bit about that?

It was quite conscious too. But I had not so consciously earlier, while she was alive, found myself writing poems which, in retrospect, were deliberately as little like Jane's as possible. This was when Jane kept getting better and better and better. Obviously the situation, two poets living together and writing together and publishing together is inherently competitive and the two of us were very good about keeping it from coming between us. It was conscious, we succeeded really. But in my ways here, I think not competing wasn't writing in a way that we're sort of the opposite of, almost anathema to the way that Jane was.

When she died, maybe the only good feeling I had was that now I didn't have to do that anymore. For the next, what, six or seven years, I didn't write about anything else, pretty much. I wrote about Jane's death and my grief and so on.

Consciously, I chose a word that she might have chosen sometimes. One that she did use, I'm trying to think of an example now … There was her poem "Afternoon at MacDowell": "I believe in the necessities of art, but what prodigy will keep you safe beside me."

I used prodigy or prodigious. In the first poem, I began about a month after she died, I was able to write about her death. I used that poem and another one that was an important, unusual, not commonly used. Even prodigy is not commonly used.

I was free to do it. It just opened up more. I'm not sure that the poems—nobody has said that the poems were trying to imitate Jane or were too much like Jane, but I knew what a difference was. It opened me up and gave me more freedom.

But it also seemed a kind of homage to the poet of "Wonderful Work and "All My Love Eternally." It died on me.

Let's go back to the prose that you've been writing. Talk a little bit about "Out the Window." I know from previous discussions that you felt like something was missing when something happened to you in Washington, D.C. that gave you something that made it such an extraordinary piece of writing.

One of my dogmas, a lot of people's dogma, is that everything has to have a counter motion within it. I wrote about looking out the window, sitting passively watching the snow against the barn, loving the barn and watching it. The home and the snow. Then I went into the other seasons I could see out the window. It was all sort of one tone, a kind of old man's love of where he lived and what in his diminished way he could enjoy without any sense of loss. OK, that was fine. I was almost finished with it at one point, and then this wonderful thing happened. [laughs]

I went to Washington with Linda [his longtime companion], and we went to the various museums. In the National Gallery, we were walking around, and there was a Henry Moore carving. I had written a book about Henry Moore. A guide came out and said, "That's Henry Moore, and there's more of them here and there." Thank you.

An hour or two later, we had lunch, this is the National Gallery. When we came out from lunch, the same guy was there. My legs have no balance, and Linda was pushing me in a wheelchair around the museum. The same guy asked Linda, "Did you like your lunch?" And Linda said, yes. Then he bent down to me in the wheelchair, stuck his finger out, waggled it, and then he got a hideous grin and said, "Did we have a good din din?"

[laughter]

And people said, "Did you pop him?" No! We were just sort of amazed, and walked away without saying anything more. But then, that made me think of … I thought it was very funny, because I was in a wheelchair I obviously had Alzheimer's, and it made me think of little pieces of condescension, and one came from the Monitor. I don't want to hurt anybody's feelings, but somebody wrote a letter. They were being perfectly kind, but they said that I seemed to be a nice old gentleman, [laughs] you know? Nice old gentleman is a phrase you use for somebody who's sort of doddering over in the corner, and you're flattering them, you're praising them. I don't know, I thought about this, but especially the story about the guard gave me the counter motion, "So, you like being old!" [laughs] Or whatever, people who condescend to you so.

I do bring somewhat. A lot of people, I got tons of mail about that essay, and people said it's really poetry, people said a lot of things. But a lot of them talked about the museum guard, and they were sort of indignant, "Why didn't you pop him?" and so on. And I've lost my track...

Terry Gross did an interview on NPR, and she brought up this guy. One person wrote in in an electronic way, several people wrote in and enjoyed it. But one said that I was an egotistical idiot for being mad at this guy because he didn't know I'd written a book about Henry Moore. Somebody else wrote in, and he corrected him too. But it got a lot of attention, that part, and I think it made the essay. I thought it was funny, and there was other kinds of condescension also. And it belonged to...as well as my pleasure of looking out the window and all these...

You had the similar experience when you went to get the National Medal of Art and someone wrote in blog that you looked like a Yeti, right?

Oh, yeah. Yeah. But that was...this was a...

I'm amazed that you're sort of amused reaction to those things. They would make me mad. It did make me mad when I read that.

And Ralph, too. And I remember Ralph's editorial pleased me enormously, the way that he took it. But, no, I didn't get mad. It was all too silly, and there was a blogger from The Post, whose articles are printed, also. She graduated from Harvard 49 years after me. [laughter]

Her job was to be outrageous and stir people up. So she printed a picture of me taken by The Associated Press in which my big beard and my uncombed hair, and I don't know … President Obama is a tall guy. I used to be a lot taller than I am now, but in any case, there I was kind of scrunched up. And it did look a little funny. She printed it and said that she had a contest for a caption to the photograph, and she warned her readers, "This is not a Yeti." I think she said, "This is the poet, Donald Hall." And I don't know how many responses she had, but they went on for page after page after page, and many of the first of them were giving captions, all of which were pretty stupid. It was all about, "Can I see your birth certificate, too," or something like that. Some of them were two or three lines long and hadn't captioned anything.

And then the counter things started to come in, and there were a lot that were really nice and there was an editor at The Weekly Standard—is that it? It's a conservative paper—who wrote a really nice thing and said he'd met me, but you know, it was an attack on the liberal Post too. He didn't make a big thing of it.

But I was extremely flattered that a message had come from Alaska. Sarah Palin had said that the WaPo, which is liberal, had insulted an 83 year old cancer survivor. She didn't know my name, apparently. [laughter] But she didn't need to. But, anyway it went on and on, and at Stanford University, they had a sort of special section of their blog for alumni in which people were defending me or saying I shouldn't be treated so badly. I was a poet, and I was serious. Some said I wasn't quite as good as they liked, but I deserved to be better treated than that. But, no, I did not … I thought it was funny. I didn't take it seriously. I don't think that the woman had anything serious to say. She was just stirring the pot. She was getting answers, doing what they wanted her to do.

So I wrote a piece about actually just about being in Washington, because I went there first when I was 16, and I went to the protest of the Vietnam War. I went there because Jimmy Carter had a party for poets, and then I went there for Obama to put the medal around my head or whatever.

He gave me something to end with that … yeah, most of it had been if anything, self flattery. I'm an important poet. I got a gold medal. You've got to downplay it, but you are saying that. So here's someone who thinks I look like a total idiot, and I could be daring, and I guess that provided the countermotion. It was right at the end. But it may have helped to, you know, cut down on the mere egotism of some of the rest of it.

Right. Why don't we talk a little more about the essays, the … You have said, I think, today, that you are revising those a great deal more than you did the final chapters of "String Too Short to be Saved" 50 plus years ago. What are you looking for in a revision? What kind of changes are you making as you work through the essays? I'm sure there's some variety of it...

You know, over your lifetime, and I'm sure yours, your prose contains a lot. I know that when I wrote "String Too Short to be Saved," it was soft and luxuriant to remember, and I had room for some images that I remember with pleasure, like "seeing a whole forest of rock maple trees knocked down by one blast of the hurricane, like combed hair." I like that. But later, when I wrote "Seasons at Eagle Pond" many years later, my prose had become much more conscious of itself, and sort of showy, and...I still like it. I probably like "Strings" prose better than that, and now it's hard to characterize it.

I think it takes so much longer, probably, not because if its nature, but because my energy is less, and maybe my imagination needs to go over a set of words many times to get it right. But I don't mind, as I've said before. I like it a lot, and I dream up new things. Some of them are funny.

All of the new essays have age in them. The first one, "Out the Window," is about age. Yeah, there's one about poetry readings, has to do with reading when you get old, and that's all. And at other points, some structures are sort of essay structure, wouldn't be newspaper structure, that I've enjoyed. It's sort of introducing, at the very beginning, something that will turn up at the end, extended, and not in just the same way. It will be sort of put down and picked up later, and I change when I do that.

I realized that I was getting into just being funny, because I'd never written much to be funny before, and I really enjoyed it. I wrote a piece that Playboy published, which was about attitudes toward smoking in the '50s or '60s and now. It just happened that I'm one of those evil people who has continued to smoke, and I'm not telling people they ought to smoke, but I think it was a funny piece in particular, and everybody enjoyed it.

I'm just on one about three beards. I wear a beard now, and most of my adult life, I guess, I've had a beard, but there have been long times, sessions when I haven't. So, I'm just talking about three beards. Is there an idea in the whole piece? Maybe, but I'm not sure. It's anecdote, and it sets off different times, and the era of different times, the '50s, you know, that sort of...

I was in Ann Arbor during the '60s and the protests, which was a way to be at the center of everything, and I enjoyed writing about that. And now, I am writing another essay, from another set of points of view, about getting old.

But I've thought of writing an essay called "Physical Malfitness," which is really about how I've always been a terrible athlete who loves sports, and how I have always sort of fallen down and been clumsy, how whatever chance I had to get out and exercise, I always had some excuse not to. But I don't know. I think I can make it so that it was funny, but maybe I've done enough of that now, or maybe I won't. I don't know. I have a few notes.

Now, these essays, many of them are what you, I think, at one time called "essays in memoir."

Yes.

I'm wondering about the license that the memoir part of it gives you. I know that the book that you recently brought out, called "Christmas at Eagle Pond," was based on a fiction, really. It's a memoir in fiction, almost.

It's all fiction. Yeah.

All fiction.

The people are all real, and it was one of those things that I've had before, where you start writing and you begin to believe it's real. It seems real. The people are distinct, and the way they talk is distinct. But I remember the people, but the actions never took place. But, you know, I knew that it hadn't happened, but in my mind, my head, writing it, almost all of it had, and, you know, it was a pleasant experience that way. In some of these essays, especially the lighter ones that I have done, I have, oh, lied about something. Maybe I've given something the wrong name, or somebody the wrong name. Every time I've done that, I've known it and I've considered it, and I, you know, I haven't thought that I harmed anything, you know, by doing it.

But, this makes no difference at all. After I was divorced in Ann Arbor, I got invited to dinner parties, so I gave dinner parties, and they were … I won't tell you all, but they were fairly comic things. But at the end, I said …

"My guests really liked my dinner parties. There were eight guests. I served eight chilled bottles of Chateau de Campe." I changed the wine to be something much more pretentious, four or five more words longer. And I did serve them wine, but I have no idea what I served them.

Right.

It was so much better to give it a name than it would be to just say one whatever it was. I don't know. So that's why I'm honest now. I've written quite a few books of prose, and except for textbooks I think all of them have been memoirs and poems. At the beginning, my poems had nothing to do with me, almost all of them. As my life has gone on, one thing I've said is I began writing fully clothed and I took off my clothes bit by bit. Now I'm writing naked.

[laughter]

That's a bit of an exaggeration, but it has its truth. In the autobiography, in "String" there is...no, I don't think there's anything in that. No, not even that. Is there anything in it that disapproves? In a way, I wrote about a cousin of mine who lived by himself and worked a lot, but he didn't do anything. I condemned him for not doing anything. I think that was just a young man's ambition. Anyway, everything else in it is positive is what I mean to say. As memoirs have gone on, I have not talked about the most intimate things. I did talk about Jane in prose and to a degree in poetry. It does sort of embarrass me to realize that my entire life I've been writing about myself. [laughs]

Why don't we close with a brief discussion of your writing habits. You're 84 years old. What are your writing habits now? What does it do for you to wake up in the morning and write?

I'll be 85 in September.

September, right.

I've been showing people a picture of me as a child and remarking that until you are 20, you want to look older than you are. From 20 to 80, you want to look younger than you are. After 80, you say, "See how old I am."

[laughter]

When I was younger, until after Jane died, I would wake up at 5:00 or 6:00 and get to work. Now I wake up feeling sluggish, more the way Jane did. It takes me a while to be able to write, but I keep it right beside me. There are two, well three, one almost finished essay and two that I'm working on. I think about either of them. If somebody is driving me up to the doctor I may be thinking about it. You know? Or in the middle of the night, I have still gotten up in the middle of the night and written notes. Most of it is too illegible in the morning to read.

[laughter]

I think they're there all the time, and I can turn to them. Oh, sometimes I'm waiting for somebody to come and they'll be here in 20 minutes. I'll know that, so I don't think I can turn myself wholly over to my work now, but it's 20 minutes. You know, I can write a page and a half and so on. Since I was 12 years old, more firmly since I was 14, having something to do has been writing something. Almost every day of my life, I always try to point … I'm doing a little work on Christmas just so I could say I worked every day, just so I can know that. Jane and I once were sent by the State Department to China and Japan. We were away for seven weeks. During that time I wrote nothing but postcards. Towards the end of it a museum director had a caption to write. His English was fine, but he wanted me to look it over.

It was two sentences, and they were perfect. But I found a way to cut it and make it one sentence. It was a clause. I did this, and I felt happiness stealing over me. I was working. I didn't care what it meant. You know? I understood enough to write it. It didn't come from my heart. It came from my love of language and messing around with it. That's what I do now, today, when I'm working.

A typical one is a sentence that begins with a main clause and then dwindles off in the preposition and sinks down. Mostly you can solve that by simply turning the sentence around, but you can't do it every time because then you'll get into the boring, repeating rhythms, and I found that the dependent clause in one sentence really belongs in the next sentence.

The story continues, but the call vacation, that the clause needs to be moved. I change it, and you know, even when it's the … That happens in the 44th or the 45th draft of the thing I've been talking about. And it pleases me, I've done something.

[laughter]

I've got something straight, and you know, I change individual words, get more precise. One thing that's kind of common is that any verb, adverb combination, can be done better with a more exact verb. You don't have to say poof quickly, but don't say dart. [laughter]

There are probably words you could use before quickly. But yes, I take out adjectives and adjectives, and then maybe that's the earliest thing I do, is take out all kinds. So many times, you know how many times in writing, I qualify. I say, "sometimes I don't remember when," and all you have to say is, "once something happened," or something. You're always cutting, very seldom adding. But sometimes you realize that you left out something important, and you put it in. And you know everything I'm talking about. I'm just doing it slower than you do it.

[laughter]

Well, thank you so much. It's been great to talk this afternoon with my friend, Donald Hall.