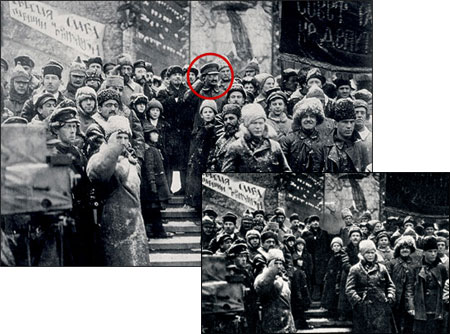

Journalists know quite well that pictures can and do lie and that photographs have been manipulated for a long time. The Soviets under Stalin were masters of this, removing political figures from images as they fell out of favor. Leon Trotsky and others would disappear from photos, erased from the historical record as their political fortunes fell.

More recently, the Fox public relations department handed out a photo of the "American Idol" judges and host which it later admitted was a composite.

Another image, sent to us by one of our photographers from a funeral in Northern Ireland some years ago, had a pixilated man in the background who had been rendered unrecognizable at the request of the activists controlling the funeral.

These are the kinds of manipulations that are fairly easy to spot. Naturally, we don't distribute them.

In recent years, however, things have gotten more complicated. News production is changing rapidly—from fewer resources in newsrooms to the use of user-generated content. Technologies to manipulate images are becoming ever more sophisticated. There are now cameras that can make the people in the pictures look skinnier, and in the latest versions of Adobe Photoshop there is the ability to make some manipulation virtually undetectable.

In this environment, the challenges for major news organizations are considerable. At The Associated Press (AP), we transmit about 3,000 images every 24 hours to subscribers around the world. That's a little over one million images a year.

In this 24-hour news cycle, timely delivery is essential. Yet if even one of the images we distribute is found to be false or deliberately misleading, our credibility and reputation are on the line.

Creating an Ethics Code

One wake-up call came in 2004 when one of our regular photographers sold us an image of flooding in China. We didn't notice anything wrong with the dramatic picture.

Shortly after, we got a message from a reader in Finland suggesting that something was amiss with the photo. We contacted the photographer and, under questioning, he admitted that he had raised the water level from people's knees to their waists for effect. We immediately terminated our relationship with him.

Over the years we have unfortunately had occasion to dismiss other photographers at the AP for manipulating imagery—and the same has happened at other news agencies and media organizations.

The question remains: what can we do about this phenomenon in photojournalism, and particularly what can we at the AP do about it?

One of the important steps to take in this new media ecology is to formulate a policy about what can and cannot be done to imagery. AP's ethics code is quite clear:

AP pictures must always tell the truth. We do not alter or digitally manipulate the content of a photograph in any way. … No element should be digitally added or subtracted from any photograph. The faces or identities of individuals must not be obscured by Photoshop or any other editing tool. Minor adjustments in Photoshop are acceptable. These include cropping, dodging and burning, conversion into grayscale, and normal toning and color adjustments that should be limited to those minimally necessary for clear and accurate reproduction …

Even these statements need to be supported by training and guidance, as words alone cannot address every possible nuance in tonality, shading and other variables.

We currently have more than 350 staff photographers and photo editors at the AP, and in the past few years we have invested substantially in a global training program designed to teach photographers and editors the best practices for using Photoshop. We have provided clear guidance on how to accurately handle images and what to do when in doubt.

The process changes somewhat when the material submitted comes from a member of the public or a citizen journalist. I first became aware of the potential of user-generated content after the London transit bombings in 2005. Explosions destroyed three subway cars and, later, a bus, killing 52 people and wounding over 700. Photographers and camera crews were limited to above-ground exit stations. The only visual entry point to the heart of the story deep underground came from cell phone photos taken by passengers evacuating through underground tunnels.

Seeing such an image on the BBC website, we contacted the person who'd taken the photo. A price was negotiated for the rights to that image and we distributed it. The next day it was widely used on front pages and across the Internet. At the time, some veteran editors, citing poor quality, dismissed the very notion out of hand. I argued that some image was better than none—and we started a sustained effort at the AP to obtain strong citizen content where and when it was needed.

Murky Origins

But the authenticity of a user-generated image isn't always as clear as it was in the London bombings, when we had access to the person who could verify ownership of the images, give us original data files, and sign an agreement.

Recently in the Middle East, for example, we've repeatedly seen events where access has been difficult or impossible for professional journalists. Local groups have been keen to share images but tracking down who actually produced a certain photo or video is extremely difficult. These images often are posted on activist websites or Facebook pages where media organizations are invited to use the material at no charge. But how do we know these images have not been manipulated or that those purporting to have permission to distribute them really do?

Like other news organizations, we try to verify as best we can that the images portray what they claim to portray. We look for elements that can support authenticity: Does the weather report say that it was sunny at the location that day? Do the shadows fall the right way considering the source of light? Is clothing consistent with what people wear in that region?

If we cannot communicate with the videographer or photographer, we will add a disclaimer that says the AP "is unable to independently verify the authenticity, content, location or date of this handout photo/video."

We also frequently work with Hany Farid, a forensic computer scientist at Dartmouth College who has developed software that can often detect photo manipulation. But it takes time to check for a variety of possible alterations and the technology, still in its infancy, cannot yet detect every skillful manipulation, such as the one that raised the floodwaters in the picture from China.

Another limitation is that full analysis of a picture often requires a large original image file. The small, low-resolution photographs distributed across social media can make it nearly impossible to detect manipulation.

All that said, I think such manipulation-detection software will become more sophisticated and useful in the future. This technology, along with robust training and clear guidelines about what is acceptable, will enable media organizations to hold the line against willful image manipulation, thus maintaining their credibility and reputation as purveyors of the truth.

Santiago Lyon, a 2004 Nieman Fellow, is a vice president and director of photography at The Associated Press.