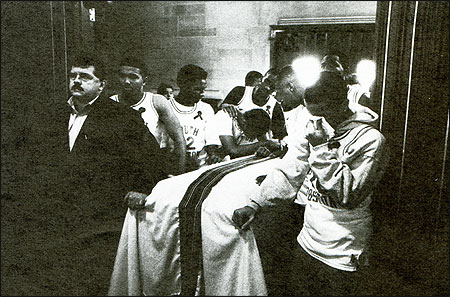

The funeral of a Boston youth. Photo by Stan Grossfeld.

There is little doubt that television coverage contributes to the public hysteria about youth crime. In particular, local television news plays a primary role in shaping what the public believes it knows about juveniles and the justice system. There are several reasons why TV stories about specific crimes—especially involving young suspects—are so ubiquitous. They are cheap to produce, often come camera-ready with gripping images, and are easy to report because they fit easily into a journalistic formula that has at its core human drama.

The increasing visibility of juveniles set in the context of crime lends credence to some people’s view that today’s youth are a new breed of “superpredators”—violent, remorseless and impulsive pre-adults responsible for widespread mayhem. Of course, the clear but unspoken subtext of the superpredator thesis is that a disproportionate number of criminal youth are from racial minority groups. To be sure, minority youth offenders are arrested for violent crimes at rates exceeding their population sizes. But those who analyze the role of TV news—as we do—find that the overwhelming focus on violent crime adds to this distortion because the dominant message is consistent with the widely held public perception that young people of color commit violent crime.

Recently we set out to examine in a novel way the connections between what people see in local newscasts and what they think about juvenile crime. We designed an experiment to assess the impact of the “superpredator news frame” in which the only difference between what groups of viewers saw in a news story involved the race of the alleged youth perpetrator.

Those who were part of this experiment were presented with a 15-minute videotaped local newscast, including commercials. It was described to them as having been selected at random from news programs broadcast that week. The report on crime was inserted into the middle of the newscast, following the first commercial break. The participants—who were found while shopping in a mall in Los Angeles—were assigned at random to one of the following groups:

- Some participants watched a news story—with a “superpredator script”—in which the close-up photo of the alleged murderer showed a young African-American or Hispanic male.

- Other participants watched the same newscast and story, except that the race of the murder suspect was white or Asian.

- A third set of viewers watched the same newscast, but this time the story did not contain any information concerning the racial identify of the accused.

- Finally, a control group did not see a crime story in the newscast.

Prior to watching the various newscasts, each participant filled out a short questionnaire. Information about their social and economic backgrounds, political beliefs, level of interest and involvement in political affairs and customary media habits was gathered. After they viewed the newscasts, a lengthier questionnaire was given, probing in more detail their social and political views. Only then was the method and purpose of the experiment explained to them.

Here’s what we discovered. A mere five-second exposure to a mug shot of African-American and Hispanic youth offenders (in a 15-minute newscast) raises levels of fear among viewers, increases their support for “get-tough” crime policies, and promotes racial stereotyping. However, we also found that these effects vary a great deal by the race of the viewer.

Exposure to the “superpredator news frame” increases fear of crime—measured as concern for random street violence and expectations about victimization—among all viewers.

The increase for white and Asian viewers is about 10 percent. The effect is more pronounced among African-Americans and Hispanics, with a 38 percent rise.

This, by itself, is not a surprising finding. After all, these two groups are most likely to be victimized and violent crime typically involves people from the same racial and ethnic backgrounds. The more pertinent question is how these fears translate into opinions about crime. We measured this by asking an open-ended question about “solutions to the crime problem” on our follow-up survey. Here is what we found.

Exposure to the “superpredator news frame” increases a desire for harsher punitive action among whites and Asians by about 11 percent.

Exposure to the “superpredator news frame” decreases support for this type of solution by 25 percent among African-Americans and Hispanics.

It is interesting that while the “superpredator script” heightens fear among all viewers, this anxiety translates into a demand for harsher and swifter punishment only among whites and Asians. Among African-Americans and Hispanics, these stories remind them of injustice and prejudice.

This finding appears consistent with the historic opposition minority groups have shown toward punitive policies such as the death penalty. Media depictions of “superpredators” remind minority viewers of this fact, while similar news images and stories strengthen the belief among whites and Asians that crime remedies for young offenders need to be harsher, in part as a result of what they’ve seen.

A similar pattern holds for how these stories affect racial stereotyping. Exposure to the image of a minority “superpredator” increases the percentage of whites and Asians who subscribe to negative stereotypes about African- Americans and Hispanics. However, among viewers from these minority groups, the tendency to attribute negative characteristics decreases by 20 percent after viewing these stories.

The “superpredator frame,” therefore, widens the racial divide among members of the viewing public. From our perspective as media analysts, we believe this study suggests why and how the practice of journalism—especially when it comes to reporting youth crime on television—should be revised. Without commenting on intent, it is enough to say that “body-bag” journalism, particularly as it focuses on young people, has a corrosive influence. There are more constructive ways of reporting these stories. Organizations such as The Berkeley Media Studies Group and television stations like KVUE in Austin, Texas have developed alternative approaches that work well in reporting the story of youth crime and reduce the racially polarizing effect that otherwise emerges.

Right now, in the minds of the viewing public, youth crime is as much about race as it is about crime. Many experts believe that efforts to curb youth violence must ultimately deal with the vexing social problems facing young people of color. If this is so, reporters ought to look at developing stories about the nature of these problems and effects they have on community safety. Unless these broader contexts are examined, and the “superpredator script” is revised, then the behavior of the troubled “eight percent” of youth will define an entire nation’s understanding of these issues.

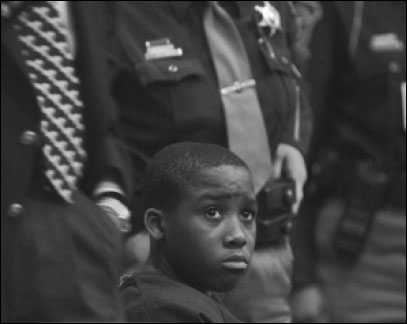

Nathaniel Abraham, 12, is being charged as an adult in a homicide case. He looks around as Sheriff’s deputies move in to re-cuff him during a break in his hearing to determine if the trial charging him as an adult will proceed. Photo by Pauline Lubens/The Detroit Free Press.

Franklin D. Gilliam Jr. is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Shanto Iyengar is Professor in the Department of Communications at Stanford University.