[This article originally appeared in the Summer 1981 issue of Nieman Reports.]

The most distressing aspect of the whole “Jimmy’s World” scandal has been the reaction of a number of editors that it could have happened to any newspaper. If this false story could get through the safety nets of any large number of newspapers, then the newspapers have been involved in much worse laxity than I had imagined. I hope this is not true.

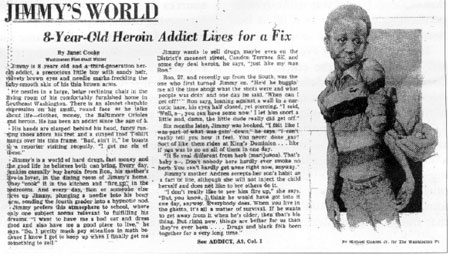

In the first place, I believe that most editors are too cautious to permit a reporter, particularly a young, totally inexperienced and untested reporter, to write this kind of story where there was no way to corroborate any aspect of the fanciful yarn about the eight-year-old heroin addict. A large number of editors would properly balk at publishing such a story from an experienced and tested reporter unless the material from the anonymous source was only one aspect of a story that could be otherwise documented and attributed to specific credible sources.

Janet Cooke’s Jimmy story used one device that should have caused questioning immediately. Public officials were quoted on the general drug problem in the District of Columbia to give an authoritative base to the story, but their statements had no specific comment on an eight-year-old heroin addict. This meant the story was devoid of any specific corroboration of the Jimmy incident.

The fiction of Janet Cooke is the natural and inevitable consequence of one of the myths of Watergate—that a Deep Throat source was such corroboration, was in fact a credible and sound “second source.” Woodward moved smoothly from Deep Throat to second, third and fourth hand hearsay in “The Final Days,” and then to the questionable use of 227 anonymous Supreme Court clerks and others as his authority in “The Brethren.”

Even if there was a Deep Throat (and I believe it is only sensible to be skeptical until he is named), that mysterious figure did not represent a sound corroboration. It is said that he did not purport to tell Bob Woodward anything that Woodward did not know already from some credible source. Deep Throat, according to what we have been told, simply volunteered that he would listen to what Bob Woodward told him and give Woodward some indication as to whether he was “right” or “wrong” or “hot” or “cold” on the facts.

Any rookie cop would be fired for any reliance upon the techniques that Woodward says he used to get the second source (Deep Throat) that he was required to produce to meet Executive Editor Ben Bradlee’s standard. Police rarely tell an informant witness what they know, but test his credibility constantly by insisting that he relate what took place with the kind of physical detail that can be established by other evidence.

The great contribution that Woodward and Carl Bernstein made to the Watergate story was their tireless checking of records and interviewing and reinterviewing of dozens of witnesses to spot contradictions and to obtain elaborations to bring the role of the Nixon White House into focus. That was fine reporting, and they were energetic and imaginative in the manner in which they did it. However, the injection of Deep Throat was without independent value except as it filled Ben Bradlee’s demand for a second source. The resignation of President Richard M. Nixon and the conviction of dozens of Watergate defendants is irrelevant to any discussion of the value of the Deep Throat source.

Washington Post reporters could just as well have developed a “third source,” a “fourth source,” and more by repeating the Watergate developments to other persons until such time as they found others who would assure them that the facts as recited were “about right.” With four, five or more so-called “sources” developed in this manner there would still be no true independent corroboration.

If Woodward and Bernstein or any of their editors truly believed that Deep Throat was an independent and credible second source, it says a great deal about the superficiality of their own analysis and the lack of discrimination between firm corroboration and what can well be a contrived “second source.”

It is well to remember that one good solid source, a direct witness with no axe to grind and with a record of high credibility, is better than two, three, four, or five sources who are relating second- or third-hand hearsay. The source who does not volunteer new information without prompting may be one of the horde of people in and out of government who like to pretend that they know more than they do to build their own reputation or simply want to be accommodating to a newsman who is seeking assurance that he is on the right track.

Any type of “two-source” or “three-source” rule is nonsense unless there is a sound standard for weighing the credibility of the source. It is also necessary that the editors establish uniform policy for administering and enforcing the “source” standards in a way that genuinely weighs the evidence and is not a mere seeking of a minimal justification for printing a sensational story from a questionable source.

All effective investigative reporters rely to some degree upon confidential sources that must remain anonymous for varying times, depending upon the nature of the threat to the source’s life or livelihood. However, every really experienced investigative reporter knows that few informants are totally reliable even though they may believe they are telling the reporter the full truth.

Frequently these informants will expand on what they know from direct conversations and observations because they believe it is probably true—and they know it is what the reporter wants to hear. A witness who is totally reliable on one subject may be deceptive and misleading where his own interests or those of family members are involved or where he has reason to dislike the person involved in the alleged mismanagement or corruption.

Any really experienced investigative reporter knows that many public officials who are quite reliable when speaking on the record will peddle a large amount of malicious misinformation when talking on a confidential basis. The investigative reporter must constantly be on guard against being used by clever informants who may make unjustified accusations against those whom the informants wish to damage.

The only real protection a reporter can give a good informant is to avoid mentioning his existence in a story and to have every paragraph fully supported by documents or independent witnesses or both. In such cases, the information taken from the confidential source is used only as leads to public records, other documents, and direct witnesses who can be quoted to establish the soundness of the informant’s allegations. While this is not always possible, it is well to keep in mind that every mention made of an anonymous source is waving a red flag in the face of lawyers for defendants or other critics. On this point, it is well to remember that even the broadest shield laws that have been enacted in some states are of little value when balanced against the Sixth Amendment rights of a defendant to have access to all of the witnesses and documents that may be of use in his defense. Myron Farber learned that sad lesson, and all of the financial resources and clout of The New York Times couldn’t save him from jail.

While I am not ruling out the possibility that there are occasions when it might be essential to quote an anonymous source in a controversial news story, it should be done sparingly. It must not be done impetuously, but must be done with careful consideration of all questions of ethics and news policy.

In pointing to the need for uniformly sound standards in the corroboration of news sources, it is not necessary to accept or reject the arguments that “Jimmy’s World” got through because The Washington Post editors and the Pulitzer Committee had undefined “pressures” to demonstrate some symbolism. Adoption and enforcement of sound operational standards for all reporters—male or female, black or white, liberal or conservative—is possible. While only a few publishers, editors, or reporters have taken the time to think their policies through completely, a sense of fairness combined with caution has served as an effective check on many newspapers. This is not enough.

The burden of proof should be upon the reporters and editors to explore thoughtfully all of the pros and cons of ethics, news policy, and general public policy. While errors can creep into any newspaper, there should be a genuine interest in making a full correction of those errors at the earliest point possible. From this standpoint the “Jimmy’s World” story was a continuing fraud that ignored the challenges with a Watergate-like attitude that called for drawing the wagons in a circle to defend against the critics. This precluded any real internal investigation. That attitude continued through the arrogant submission of the story for the Pulitzer award and the proud reprinting of the story in a full-page promotional advertisement on April 14, 1981.

The continuing fraud of a “Jimmy’s World” story would not escape the editors of any responsible newspaper who are interested in sound reporting and are not seeking bare justification for publishing a colorful yarn. There are times when sticking by a reporter and a story takes courage, but there are other times when it is foolhardy. Mature judgment in weighing corroboration for informants is the difference.

Clark R. Mollenhoff, Nieman Fellow 1950, is Professor of Journalism at Washington and Lee University. His latest book is “Investigative Reporting—From Courthouse to White House.”