Our editors come to work three afternoons each week after six hours of school. They arrive at our downtown office from all over Boston, especially from economically disadvantaged parts, places where there isn’t a lot of political capital. They read writing sent in from across the United States and around the world by young women whose lives are like and unlike theirs. They come to learn and be supported by writing mentors. They also come to move words and images onto the pages of our magazine to portray the experiences, feelings and opinions of female teenage writers.

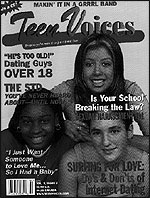

Each earns a small monthly stipend for her role in creating the national, quarterly young women’s magazine, Teen Voices, and the bimonthly Teen Voices Online. Empowering teenagers to write for an audience of other young women, Teen Voices has, for 11 years, worked hard to bring the concept of people’s journalism—media in which people speak for themselves—to the people.

As senior editor of this process, it is my job to train and guide both mentors and teen editors. I work with them on not only the journalism techniques they’ll need to use, but also on the politics behind the language and images, so that various perspectives are spoken to and included within the pages of Teen Voices. This involves, for example, trying to make sure the Love Poems section does not solely include poems on heterosexual love. (Not many teens feel safe exploring or expressing their sexuality.) And I make sure our volunteer artists from across the country do not illustrate solely based on a stereotypical idea of beauty.

Teen Voices is a magazine that strives to truly include and represent all of its readers’ experiences as well as to critically examine America’s oppressive myths. But this goal is not easily attained through attending a couple of workshops or mentoring sessions. Constant questioning and challenging of ideas and assumptions goes on among teen editors and their mentors (mostly volunteer journalists or students like myself). Not all of the teens who join our magazine believe totally in or understand fully our mission of addressing social and economic justice. Many think their voices are enough, even when they are not challenging society’s myths. Often, as a result, many are left feeling disillusioned with their positions at Teen Voices.

“But what about my voice?” is a question that often comes up during meetings I have with teen editors and their mentors after they have received their drafts with lots of edits from me and the magazine’s editor in chief. Many of them are not exposed to critical thinking in school or at home, so when we pose editorial questions they are often received negatively. The editing process is hard for adults; imagine the impact it has on a 14-year-old girl who exposed her personal angst in what she considered to be her best writing. To deal with this, we have begun a workshop called “The Editorial Process,” in which I act out my role and one of our writing mentors leads the discussion on the relationship between writers and editor while I edit an article in front of the group. This has helped, but sometimes our discussions go deeper than any workshop exercise can help.

Just as white faces are not allowed to adorn every page of Teen Voices, academic jargon and local slang do not get into the editorials of Teen Voices without being properly vetted for their alienating tendencies. And editors’ personal experiences are not to outshine the experiences of others. In striving to be as inclusive as possible, an editor for Teen Voices must constantly think about how to help each reader feel as though she matters and that she is not alone in her experiences.

“You are more than just a pretty face,” is our magazine’s slogan, and it goes to the heart of what we firmly believe and know resonates with many young women: They are more than make-up, clothes, boyfriend seekers, and gossip tellers. Certainly, their lives and circumstances are more varied than the usual images of upper-middle-class, suburban whiteness that appear in most teen movies and advertisements. What happens in the lives of many young women involves issues that are often at the heart of our nation’s political debates. To these teens, the personal is political, even if politicians often forget to refer to them in their examples of American life.

The challenge for us—as editors of this unique teen magazine—is that we work at a distance from those whose lives we might influence through what we publish. Our mission is to empower young women to achieve social and economic justice, so it is not surprising that the young women we do work with directly are teens who have grown up in underprivileged neighborhoods and have had few or no resources for upward mobility. Most of them come from urban, low-income, often single-mother families. They are mostly teens of color and often first-generation American citizens. Their experiences range from their fathers being deported to their countries of origin to losing their mothers to cancer, to being shipped from foster home to foster home, to becoming pregnant and being physically abused by their boyfriends. Many are also constantly pressured by family members to work at McDonald’s rather than work alongside the extraordinary women at Teen Voices.

These are young women whose efforts are often overlooked at school because they don’t measure up to middle-class standards. Unable to excel in school or even meet teachers’ expectations, many of them fall farther and farther behind. At Teen Voices, they are encouraged and supported in their efforts to communicate their feelings and experiences. Here, they are empowered with the resources (mentoring sessions and Friday journalism workshops) to inform their peers across the divides of class, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, and educational exposure.

Depending on what happens during recruiting sessions, we are also not always able to work with a diverse group of volunteer mentors. Some of our writing mentors don’t come from urban backgrounds, nor have they experienced domestic violence. But they do come from all parts of the United States, from different ethnic, racial and cultural backgrounds, and are often excellent teachers. They are usually young women college students who are eager to be involved with teens in a way that can bring about meaningful change.

To keep our editorial content meaningful for the young women who cannot physically be part of our editorial process, we ask each other questions. “Will a teenager in Oklahoma feel awkward reading b-cuz?” Or, “Should we include an editor’s note to readers explaining that some agreed to work on this feature even though they don’t believe in homosexuality?” (B-cuz was approved for its phonetic readability, and after a lengthy and personally revealing discussion it was determined that such an editor’s note would take away the power of these women’s words and make it harder for other readers to see their experiences for what they are.)

Hard feelings are often part of our editorial process. Editors sometimes feel that they are not being heard because either I or the editor in chief urged them to move in a different direction. Even though I’ve been doing this for three years, I sometimes feel that I am shattering worldly truths rather than acting as a tough, progressive editor. But then, when I least expect it, an editor will seek me out and tell me she is happy about the decision we made together and proud of the feature. This is my favorite part of the process.

How do we keep doing what we do when Teen Voices doesn’t have any money? We all put in more sweat labor than paid labor to start with. Because of our strict advertising policy of not publishing any ads in Teen Voices that portray young women as desperately seeking make-up and as fashion fanatics, it makes it really hard to compete with other youth media. But our difficulty with advertising doesn’t stop there: Companies that we’d like to advertise in Teen Voices—such as health food stores, big-name computer companies and educational resources—do not regard young women as worthwhile constituents. As a result, we can’t afford to purchase the most up-to-date computers or fast Internet connections. Our office furniture is hand-me-down stuff, and in the winter we don’t have much heat or, in the summer, cool air. We can’t even pay the teen editors minimum wage, though we know their families rely on their monthly stipends.

Somehow we keep doing this day in and day out, loving what we do. And somehow our four-color, glossy magazine, filled with the true writings and illustrations of young women from around the globe, makes its way to the newsstands and into the hands of our dedicated readers.

Celina De León, 22, is senior editor of Teen Voices magazine. She began her stay at Teen Voices three years ago as a volunteer writing mentor, and became senior editor nine months later. She is also a senior at Northeastern University majoring in print journalism with a special concentration in women’s studies. De León is a Presidential Scholar Award recipient. She worked at The Boston Globe for two years as a promotional copywriter.

Each earns a small monthly stipend for her role in creating the national, quarterly young women’s magazine, Teen Voices, and the bimonthly Teen Voices Online. Empowering teenagers to write for an audience of other young women, Teen Voices has, for 11 years, worked hard to bring the concept of people’s journalism—media in which people speak for themselves—to the people.

As senior editor of this process, it is my job to train and guide both mentors and teen editors. I work with them on not only the journalism techniques they’ll need to use, but also on the politics behind the language and images, so that various perspectives are spoken to and included within the pages of Teen Voices. This involves, for example, trying to make sure the Love Poems section does not solely include poems on heterosexual love. (Not many teens feel safe exploring or expressing their sexuality.) And I make sure our volunteer artists from across the country do not illustrate solely based on a stereotypical idea of beauty.

Teen Voices is a magazine that strives to truly include and represent all of its readers’ experiences as well as to critically examine America’s oppressive myths. But this goal is not easily attained through attending a couple of workshops or mentoring sessions. Constant questioning and challenging of ideas and assumptions goes on among teen editors and their mentors (mostly volunteer journalists or students like myself). Not all of the teens who join our magazine believe totally in or understand fully our mission of addressing social and economic justice. Many think their voices are enough, even when they are not challenging society’s myths. Often, as a result, many are left feeling disillusioned with their positions at Teen Voices.

“But what about my voice?” is a question that often comes up during meetings I have with teen editors and their mentors after they have received their drafts with lots of edits from me and the magazine’s editor in chief. Many of them are not exposed to critical thinking in school or at home, so when we pose editorial questions they are often received negatively. The editing process is hard for adults; imagine the impact it has on a 14-year-old girl who exposed her personal angst in what she considered to be her best writing. To deal with this, we have begun a workshop called “The Editorial Process,” in which I act out my role and one of our writing mentors leads the discussion on the relationship between writers and editor while I edit an article in front of the group. This has helped, but sometimes our discussions go deeper than any workshop exercise can help.

Just as white faces are not allowed to adorn every page of Teen Voices, academic jargon and local slang do not get into the editorials of Teen Voices without being properly vetted for their alienating tendencies. And editors’ personal experiences are not to outshine the experiences of others. In striving to be as inclusive as possible, an editor for Teen Voices must constantly think about how to help each reader feel as though she matters and that she is not alone in her experiences.

“You are more than just a pretty face,” is our magazine’s slogan, and it goes to the heart of what we firmly believe and know resonates with many young women: They are more than make-up, clothes, boyfriend seekers, and gossip tellers. Certainly, their lives and circumstances are more varied than the usual images of upper-middle-class, suburban whiteness that appear in most teen movies and advertisements. What happens in the lives of many young women involves issues that are often at the heart of our nation’s political debates. To these teens, the personal is political, even if politicians often forget to refer to them in their examples of American life.

The challenge for us—as editors of this unique teen magazine—is that we work at a distance from those whose lives we might influence through what we publish. Our mission is to empower young women to achieve social and economic justice, so it is not surprising that the young women we do work with directly are teens who have grown up in underprivileged neighborhoods and have had few or no resources for upward mobility. Most of them come from urban, low-income, often single-mother families. They are mostly teens of color and often first-generation American citizens. Their experiences range from their fathers being deported to their countries of origin to losing their mothers to cancer, to being shipped from foster home to foster home, to becoming pregnant and being physically abused by their boyfriends. Many are also constantly pressured by family members to work at McDonald’s rather than work alongside the extraordinary women at Teen Voices.

These are young women whose efforts are often overlooked at school because they don’t measure up to middle-class standards. Unable to excel in school or even meet teachers’ expectations, many of them fall farther and farther behind. At Teen Voices, they are encouraged and supported in their efforts to communicate their feelings and experiences. Here, they are empowered with the resources (mentoring sessions and Friday journalism workshops) to inform their peers across the divides of class, ethnicity, race, sexual orientation, and educational exposure.

Depending on what happens during recruiting sessions, we are also not always able to work with a diverse group of volunteer mentors. Some of our writing mentors don’t come from urban backgrounds, nor have they experienced domestic violence. But they do come from all parts of the United States, from different ethnic, racial and cultural backgrounds, and are often excellent teachers. They are usually young women college students who are eager to be involved with teens in a way that can bring about meaningful change.

To keep our editorial content meaningful for the young women who cannot physically be part of our editorial process, we ask each other questions. “Will a teenager in Oklahoma feel awkward reading b-cuz?” Or, “Should we include an editor’s note to readers explaining that some agreed to work on this feature even though they don’t believe in homosexuality?” (B-cuz was approved for its phonetic readability, and after a lengthy and personally revealing discussion it was determined that such an editor’s note would take away the power of these women’s words and make it harder for other readers to see their experiences for what they are.)

Hard feelings are often part of our editorial process. Editors sometimes feel that they are not being heard because either I or the editor in chief urged them to move in a different direction. Even though I’ve been doing this for three years, I sometimes feel that I am shattering worldly truths rather than acting as a tough, progressive editor. But then, when I least expect it, an editor will seek me out and tell me she is happy about the decision we made together and proud of the feature. This is my favorite part of the process.

How do we keep doing what we do when Teen Voices doesn’t have any money? We all put in more sweat labor than paid labor to start with. Because of our strict advertising policy of not publishing any ads in Teen Voices that portray young women as desperately seeking make-up and as fashion fanatics, it makes it really hard to compete with other youth media. But our difficulty with advertising doesn’t stop there: Companies that we’d like to advertise in Teen Voices—such as health food stores, big-name computer companies and educational resources—do not regard young women as worthwhile constituents. As a result, we can’t afford to purchase the most up-to-date computers or fast Internet connections. Our office furniture is hand-me-down stuff, and in the winter we don’t have much heat or, in the summer, cool air. We can’t even pay the teen editors minimum wage, though we know their families rely on their monthly stipends.

Somehow we keep doing this day in and day out, loving what we do. And somehow our four-color, glossy magazine, filled with the true writings and illustrations of young women from around the globe, makes its way to the newsstands and into the hands of our dedicated readers.

Celina De León, 22, is senior editor of Teen Voices magazine. She began her stay at Teen Voices three years ago as a volunteer writing mentor, and became senior editor nine months later. She is also a senior at Northeastern University majoring in print journalism with a special concentration in women’s studies. De León is a Presidential Scholar Award recipient. She worked at The Boston Globe for two years as a promotional copywriter.