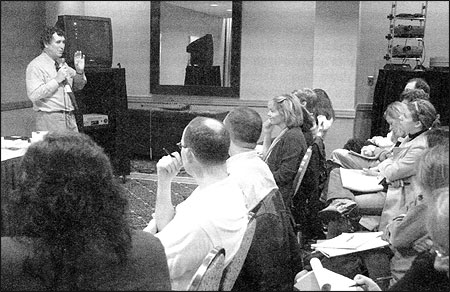

David Fanning talks about finding the story in TV documentary.

Learn the rules and the conventions of your craft so you can break them. That’s how you wing walk. That’s how you take risks. You take risks on the platform of security so you know where you are starting and where you have to land.

You do not pop fully formed from the womb ready to write a Pulitzer-quality piece. You have practiced writing long and hard, all of you, but the harder truth is you have to keep practicing and keep practicing again. You’re never done—that’s both the challenge and the beauty.

Don’t assume that narrative or what we’re talking about here is defined by length. Don’t try to squeeze the dress of narrative over the wrong form. If there’s a lesson to be learned here it’s that narrative does come in one line, one moment in time.

The other thing I want to remind you of is you can’t just say, “I want to do a narrative” and go out and find a story and then wrench a narrative on top of it. It’s like dressing up a pig: Sometimes it doesn’t work. You have to be open to the possibility of stories that come your way, especially if you work in the real world, and you’ve got to do assignments and you’ve got to do what your editors do, and then, when the right story comes along, you have to look for the opportunity to see the narrative in it.

The other lesson is that you have to stretch yourself, and you have to work with muscles that aren’t as natural and comfortable to you. Just know you’re going to have to be uncomfortable for a while.

The other thing you have to remember how to do is to get in close. You have to wipe the brow of the AIDS patient. You have to hold the baby in your arms in the moments before it dies. You have to be willing to immerse yourself in a story so much that, even if you can’t live the story, you can soak it up for a little while.

Writing is personal. It is direct from me to you, one-on-one, and the more massive your circulation, the more massive your publication or audience, the more personal and direct it needs to be. I’m not talking about first person necessarily, or even very often, but I am talking about writing with a reader in mind, writing with the core conscious purpose of communicating very directly from you to a reader what happened, what you experienced, what you felt, what was going on, and what you want them to understand and know.

I can’t write for 500,000 people. I don’t know who they are. I don’t care how many readership surveys you take, I don’t know who 500,000 people are. So when I wrote, I wrote for five. They had names and real lives and faces and their pictures were up on my computer terminal. I had to look at them as I wrote, and they kept me honest when I grew too invested in my sources or too infatuated with my own prose.

Another lesson: Stories are oral. If you want to do narrative, one of the truisms of narrative is that it really is a story that has to be able to be read aloud. People learned language by listening to stories and listening to language. We didn’t grow up reading. We grew up hearing, and eventually we absorbed the written word. When people read, there is an inner oral ear that their mind hears with. And if you are going to tell a true narrative, you’d better be able to tell it orally. So read your things out loud. Have other people read them out loud, and see if they work for you. See if they truly are stories and they have rhythm and pace and cadence and flow and if they move along.

The final lesson from this is you need to take a risk, and what you are risking is yourself. You are the one on the scene, in the interview, at the core heat of the story. And you have to let your readers into that place or you are cheating them for the sake of your own comfort.