A decade ago, as a photojournalist with The Boston Globe, I embarked on a worldwide journey to document environmental destruction. What I learned along the way is why environmental issues can be so difficult to cover and why it is essential to connect the human experience to what we see happening around us.

News coverage of environmental issues can be difficult, in part, because those who are affected—whether the effect is economic or environmental—routinely exaggerate their claims. Non-governmental organization advocates pull “facts” in one direction; big business tugs them in another, and sometimes neither leaves the cushy offices in the northwest section of Washington, D.C. Truth resides in a place somewhere in between. But this truth can be impossible for anyone to gauge. The power of photography is to go beyond statistics and offer humanity.

I listened to what scientists observed was happening, but I kept my camera’s eye fixed on the haunting faces of children. At times, I allowed my eye to wander and bear witness to the conditions of adults, as well. Their expressions and circumstances bespoke the consequences of the environmental tragedies in ways that any retelling of the experts’ verbal arguments never could.

China pollution:

The air in China is among the world’s worst, having six times the World Health Organization standard for suspended pollutants. There’s a saying in China: “From the sparrows in the sky to the intestines of pigs, everything is black.” Near mines in Taiyuan, roads are black with spillage of overloaded trucks. Children with sooty faces dodge traffic and scoop bucketfuls of coal to heat their homes. When it rains, rivers form that look as black as ink. —S.G.

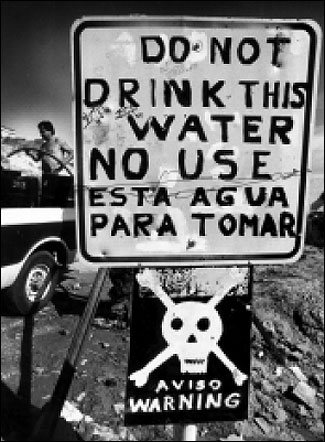

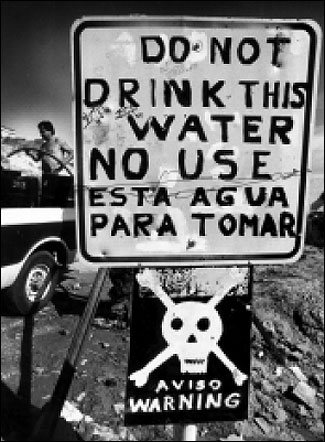

South Texas water:

The United States creates a bounty of agricultural wealth. But the migrant workers who harvest this food are routinely subjected to dangerous pesticides and abusive bosses who don’t even provide basic sanitary facilities in the fields. In the colonias of South Texas, there is no running water. Migrants must boil water for drinking. —S.G.

Brazilian rain forest:

When I visited the Brazilian rain forest after the Earth Summit, I felt no rain and saw no forest. What I witnessed was the epicenter of hell. To children there, who were sentenced to a life of making charcoal, the word “sting” held far more meaning than the man, Sting, who was fighting to save the rain forest, did. Families live in company-made makeshift huts set back from the burning edge and appear like ghosts as the wind shifts. —S.G.

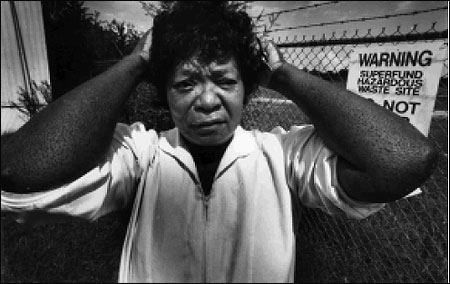

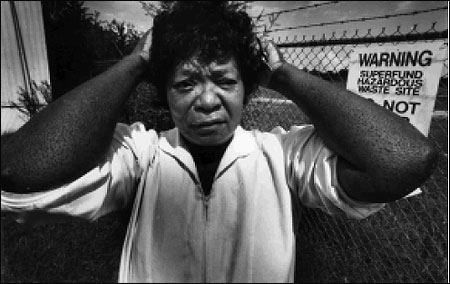

Mississippi rash:

Virgie Peavy’s body became covered with rashes after she ate collard greens picked from her backyard in Columbia, Mississippi. Her yard adjoins the former site of Reichhold Chemical Inc., which produced a substance used in wood preservation. In 1977 an explosion occurred at the Reichhold Chemicals Inc. facility, and area residents said they were allowed to return to their homes while the fire still burned. A decade later, this was declared a Superfund site and 3,900 barrels of hazardous waste were unearthed.

“The doctor wanted tests. I didn’t have the money,” said Peavy, when I met her in 1991. “Then I got a settlement. I didn’t never read it. I was too greedy. But now I’m sick. I got problems with nerves. It got worse.”

It is not unusual for toxic waste sites to be found in communities of color or in places where poor and lowincome families live. For big business, these communities provide the path of least resistance. Today, the Peavy family lives in the same house in Columbia, but Virgie Peavy is gone. “She got cancer all over her body,” said Roosevelt Peavy, her son. “That settlement she got was small. She never got rid of the rashes, and then she passed away.” —S.G.

Stan Grossfeld is an associate editor and a photographer for The Boston Globe.

News coverage of environmental issues can be difficult, in part, because those who are affected—whether the effect is economic or environmental—routinely exaggerate their claims. Non-governmental organization advocates pull “facts” in one direction; big business tugs them in another, and sometimes neither leaves the cushy offices in the northwest section of Washington, D.C. Truth resides in a place somewhere in between. But this truth can be impossible for anyone to gauge. The power of photography is to go beyond statistics and offer humanity.

I listened to what scientists observed was happening, but I kept my camera’s eye fixed on the haunting faces of children. At times, I allowed my eye to wander and bear witness to the conditions of adults, as well. Their expressions and circumstances bespoke the consequences of the environmental tragedies in ways that any retelling of the experts’ verbal arguments never could.

China pollution:

The air in China is among the world’s worst, having six times the World Health Organization standard for suspended pollutants. There’s a saying in China: “From the sparrows in the sky to the intestines of pigs, everything is black.” Near mines in Taiyuan, roads are black with spillage of overloaded trucks. Children with sooty faces dodge traffic and scoop bucketfuls of coal to heat their homes. When it rains, rivers form that look as black as ink. —S.G.

South Texas water:

The United States creates a bounty of agricultural wealth. But the migrant workers who harvest this food are routinely subjected to dangerous pesticides and abusive bosses who don’t even provide basic sanitary facilities in the fields. In the colonias of South Texas, there is no running water. Migrants must boil water for drinking. —S.G.

Brazilian rain forest:

When I visited the Brazilian rain forest after the Earth Summit, I felt no rain and saw no forest. What I witnessed was the epicenter of hell. To children there, who were sentenced to a life of making charcoal, the word “sting” held far more meaning than the man, Sting, who was fighting to save the rain forest, did. Families live in company-made makeshift huts set back from the burning edge and appear like ghosts as the wind shifts. —S.G.

Mississippi rash:

Virgie Peavy’s body became covered with rashes after she ate collard greens picked from her backyard in Columbia, Mississippi. Her yard adjoins the former site of Reichhold Chemical Inc., which produced a substance used in wood preservation. In 1977 an explosion occurred at the Reichhold Chemicals Inc. facility, and area residents said they were allowed to return to their homes while the fire still burned. A decade later, this was declared a Superfund site and 3,900 barrels of hazardous waste were unearthed.

“The doctor wanted tests. I didn’t have the money,” said Peavy, when I met her in 1991. “Then I got a settlement. I didn’t never read it. I was too greedy. But now I’m sick. I got problems with nerves. It got worse.”

It is not unusual for toxic waste sites to be found in communities of color or in places where poor and lowincome families live. For big business, these communities provide the path of least resistance. Today, the Peavy family lives in the same house in Columbia, but Virgie Peavy is gone. “She got cancer all over her body,” said Roosevelt Peavy, her son. “That settlement she got was small. She never got rid of the rashes, and then she passed away.” —S.G.

Stan Grossfeld is an associate editor and a photographer for The Boston Globe.