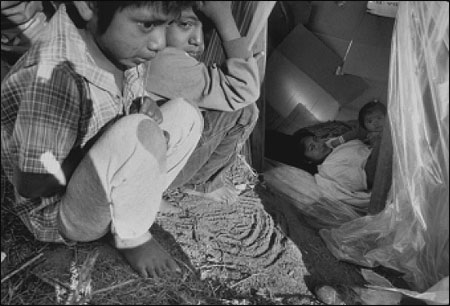

An undocumented family of strawberry pickers from southern Mexico hiding in a makeshift hole in Southern California after a day’s work in the fields. Photo by Liliana Nieto del Rio.

“I cover immigration.” That has been my mantra for much of the past two decades. It sounds self-explanatory, as if to say, “I cover City Hall,” or “I cover the White House.” But, in important ways, documenting the immigration story is a singular experience compared to other, more traditional beats. The immigration beat more than makes up in substance what it lacks in newsroom cachet.

For one thing, the immigration story has a freeform quality that can be liberating. It generally lacks the daily grind of press conferences, canned statements, hyped developments, and other pseudo-news that tend to clutter the existences of even the best reporters. Of course, there are breaking stories that absolutely need to be covered—a surge of migrant rafts appears off the Florida Keys; a border patrolman shoots a Texas goat herder; inmates revolt at an immigration lockup. But chasing such episodes comes with the nittygritty of any beat.

As a rule, though, few if any editors will even know the name of the area Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) chief, for instance. (All will inevitably be able to identify the mayor, police chief, sheriff, etc., and might even have strong opinions about these ostensible newsmakers.) This pervasive knowledge gap about immigration can be a plus: It allows resourceful reporters the space to follow their instincts, almost always the best route to creative, unpredictable journalism.

The point here is reportorial freedom, coin of the realm of distinct journalism. The best editors—those not hung up on “managing” enterprising and passionate reporters mischaracterized as “high maintenance”—know that the most compelling stories emerge from journalists prowling around out in the world, far from desks and memos and meetings. Some dead ends are inevitable.

Would-be immigrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border at night with the San Diego, California city lights in the background. Photo by Liliana Nieto del Rio.

The Immigration Beat

The fact is, virtually no one—certainly few editors—has a fully formed vision of what the immigration beat is supposed to entail. Immigration policy and law can be so complex as to stump experienced trial lawyers. And yet this seeming paradox: Millions closely follow the twists of the immigration debate, many turning to the ethnic press for developments that fall below the radar screen of the mainstream media. The immigration beat may seem pretty far down on the newsroom hierarchy, but a lot of people care. Nuanced coverage is appreciated.

Why is there so much unfamiliarity among journalists about immigration? Generational and cultural factors have a lot to do with it. The reemergence of large-scale immigration in this country is a relatively recent phenomenon, one the press didn’t start attempting to come to terms with seriously until the mid-1980’s or early 1990’s. By that time, a lot of the people who are today’s newsroom veterans had already formed their core journalistic agendas. Many of us were products of the civil rights era and tended to view the nation’s racial/ethnic make-up through a whiteblack lens. Immigration questions seemed peripheral, as well as being hopelessly convoluted, full of inconsistencies, maddening subtleties, and shades of meaning.

This is changing now, especially among younger journalists. It’s heartening to see how many new reporters are enthused about mining the field for stories—though some must negotiate around editors who suspect they are too sympathetic to the immigrant plight. Many of these younger reporters came of age in the new America, a place that did indeed grow more ethnically “diverse” (pardon the buzzword) in the past two decades or so. Quite a few (like myself) are the children of immigrants, or immigrants themselves. A personal immigrant experience—the lingering sense of exile, loss and apartness that can persist for generations—is something that marks you for life, for better or worse.

But the immigration beat’s fundamental allure isn’t a question of reportorial freedom or newsroom positioning. Lots of financial and other beats rely on insider’s knowledge; nearly every topic can be approached in a nonconventional manner. Rather, the great beauty is the range of coverage possible under the immigration umbrella—and the sense that one is documenting a great social transformation.

I first arrived as a reporter in California at a time when thousands gathered each evening along the canyons and river levee in Tijuana, marching north at dusk like worshipers on a hurried pilgrimage, negotiating brush, swamps and freeways in all weather conditions. The nightly tableau was truly startling. Yet, at that time, we in the press seemed less interested in the long-term consequences. Surely, this level of sustained mass movement of people had farreaching implications beyond the borderlands.

The border led me to thematically linked stories like the sweatshop economy, examining the effects of Washington’s efforts to “reform” immigration law, writing about the stunning Latino political rise in California, analyzing ethnic change across the country, to name a few topics. Then there are all the “foreign” stories associated with immigration, from civil strife in Central America, the Caribbean, and Asia to the ongoing political upheaval in Mexico. Immigration became a kind of prism through which to view a dynamic social and cultural evolution. And September 11, 2001 exposed a whole new constellation of concerns, all orbiting around a central question: How does a country keep potential terrorist infiltrators out of an open society?

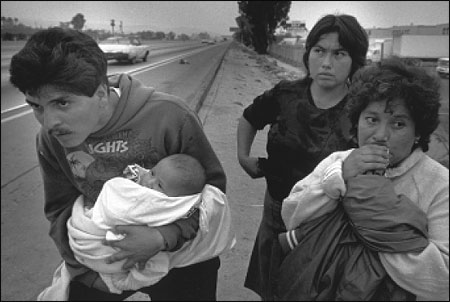

A tired and frightened family keeps watch on U.S. border patrol as they look out for oncoming cars before running across an interstate freeway near San Diego, California. Photo by Liliana Nieto del Rio.

A tired and frightened family keeps watch on U.S. border patrol as they look out for oncoming cars before running across an interstate freeway near San Diego, California. Photo by Liliana Nieto del Rio.Finding the Unpredictable Stories

Of late, the years spent courting sources and grappling with often arcane guidelines have paid off handsomely in the currency of fresh angles and scoops. One caveat about covering immigration: The topic does tend to draw a lot of predictable reporting—focusing, say, on the exploitation of guileless immigrants or, at the other end of the spectrum, unscrupulous newcomers scamming the system. As with any beat, the best stories tend to be found below the surface. The backlash to immigration that lit up the political klieg lights in California during the mid-1990’s snuck up on the press. A lot of us just hadn’t taken notice of how enraged many native-born U.S. residents had become about the seismic shift in the state’s demography. Some journalists dismissed the reaction as merely racist—a vast oversimplification. This was a case in which bleeding-heart, kneejerk reactions and untested preconceptions didn’t help elucidate the real story. As with so much good journalism, covering immigration should force reporters to process viewpoints and arguments alien to their own.

As I write this, I am sitting in Rome, a city that, if you haven’t visited it lately, is a good place to view the immigration story in global context. La dolce vita proceeds apace—and is sweeter than ever for many Italians. But these days cheap immigrant labor helps sustain the good life in the Eternal City. The guys at the car wash are Peruvians, the cleaning staff in the building across the street is Sri Lankan, the nannies pushing strollers tend to be Filipino, the street merchants African, the manual laborers Eastern European, and the hands picking grapes for the national beverage are often young Arabs.

Every Western nation is grappling with some kind of trauma about foreign settlers. Anti-immigrant demagoguery and fears of the spread of Islamic fundamentalism are now news staples in Europe. Mass immigration is one of the defining social issues of our time—and also one of the most misunderstood. The immigration story has legs, especially as economies founder and people look for scapegoats, as we saw in California a few years ago. Immigrants and refugees are not going away. In fact, multitudes are en route at this moment, on foot, aboard ships and aircraft, crammed into vehicles, however they can make the journey. And their impacts are to be measured far beyond the workplace. As someone once said about the Germans, “They wanted workers, but they got people.”

The news business needs more curious recruits with some heart, smarts and energy who grasp the phenomenon for the profound one that it is.

“I cover immigration.” It’s an admission to be proud of as the new millennium marches on.

Patrick J. McDonnell is a staff writer for the Los Angeles Times and a 2000 Nieman Fellow, who says he feels privileged to have been at Harvard during Bill Kovach’s final year at Lippmann House.