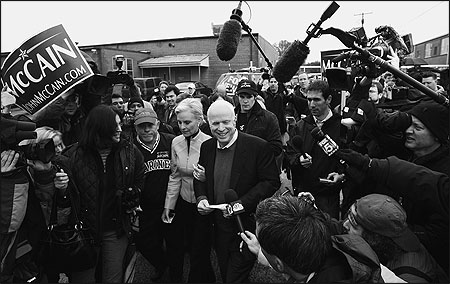

Senator John McCain, accompanied by his wife, Cindy, leaves West Ashley Middle School after an appearance at the polling station on the day of South Carolina’s Republican presidential primary. January 2008. Photo by Alan Hawes/The Post and Courier.

We are now in the midst of, I think it is safe to say, the most covered election in the history of civilization. On the surface of it, this is an objectively good thing. We haven't picked a new President for nearly a decade, and naturally there's an abundance of issues voters need to be informed about. And excellent campaign coverage has been produced: From the very beginning of this interminable primary contest, there have been subtle and edifying explorations of candidates' policy positions and histories — as well as views of voters and the situations they face — in newspapers, magazines and on the Web. (Sorry cable news, no plaudits for you.)

But. But. There's also been a whole lot of trivinalia — superficiality, posturing and posing from media persona (e.g. well-paid pundits telling us how the working class people think) and obsessive blundering down rabbit holes of inanity. Ask people inside of the industry and out what they think of the campaign coverage, and most will tell you it sucks. Why?

There are a number of reasons, but the first is that the entire approach to covering campaigns is hopelessly flawed and puts reporters in positions in which they can't help but produce frivolity. Typically, news organizations assign a reporter to cover a certain candidate, and that reporter spends all day, every day, following the candidate around, going from photo-op to speech to photo-op, and hoping to squeeze in some face-time in between. (Newspapers' and broadcast stations' tough financial times — with cutbacks in the newsroom and bureaus — mean fewer such long-term arrangements in this election cycle, but the pattern of one reporter, one candidate still tends to hold true.) I first got an inkling of this in 2004 when working as an organizer in Madison, Wisconsin during the final days of the Kerry campaign. I went to a big Kerry rally and saw the haggard press corps straggle in after him and sit with their laptops listening to a stump speech that by that point they must have heard more than 100 times.

When reporters are put in that position, what do they do? After sitting through endless, mind-numbing hours listening to the candidate spew the same safe twaddle, any one of them is going to inevitably snoop around for new "angles." John Kerry has a butler! There are lots of kids on the trail! Al Gore sighed during the debate! All this shallow fumbling is just a natural outgrowth of the need to break up the sheer monotony of the campaign.

Press Psychology

The psychology of the political press is pivotal here. Reporting at campaign events is exciting and invigorating but also terrifying. I've done it now a number of times at conventions and such, and in the past I was pretty much alone the entire time. I didn't know any other reporters, so I kept to myself and tried to navigate the tangle of schedules, parking lots, hotels and event venues. It's daunting, and the whole time you think: "Am I missing something? What's going on? Oh man, I should go interview that guy in the parka with the 15 buttons on his hat." You fear getting lost, missing some important piece of news, or making an ass out of yourself when you have to muster up that little burst of confidence it takes to walk up to a stranger and start asking them questions.

Of course, it's amazing work. But as I realized for the first time this campaign season, such a feeling of essential terror isn't just the byproduct of inexperience. It never goes away. That's the epistemic conundrum of political reporting: Ultimately what goes on in an election happens inside a black box called the voter's head and, as a political reporter, you have a remarkably crude set of tools to try and peer in there. And so veteran reporters are just as panicked about getting lost or missing something, just as confused about whom to talk to. And this is why reporters move in packs. It's like the first week of freshman orientation, when you hopped around to parties in groups of three dozen because no one wanted to miss something or knew where anything was. As one reporter that I know and respect said to me the morning after the New Hampshire primary, "Well, I got it wrong, but at least we all got it wrong."

Then there's always the fact that when you go to one of these campaign events as a reporter, there's part of you that's aware that you don't really belong there. You're an outsider, standing on the edges, observing the people who are there doing the actual stuff of politics: listening to a candidate, cheering, participating. So reporters run with that distance: they crack wise, they kibbitz in the back, they play up their detachment. That leads to coverage that is often weirdly condescending and removed from the experience of politics.

I'm convinced that some of the worst features of campaign reporting emanate from the kinds of psychological defenses that reporters erect to deal with their insecurities. That's not meant as an excuse. But I think many critiques of the political press express the belief that what's wrong with coverage stems from the superficiality and venality of those who are practicing it. While that's certainly true in some cases, just as you can't hope to fundamentally reform education by calling for a lot more great teachers, political coverage won't be made better by simply hoping for better reporters. Structural issues that reinforce these tendencies need to be dealt with. (Oh, yes, and fire the hacks.)

To take one example, there's the perennial complaint that media coverage focuses on the horserace and the campaign theater and not on the issues. But I don't really think that's the fault of reporters. First, they have to file constantly on tight deadlines. So even if Obama releases a tax plan one day and that gets written about, it's likely to be a one-day story. What's the next day's story? Well, it's Obama sniping with Clinton or some such. Secondly, consider the imbalance in expertise between a campaign and those who cover it. When a candidate releases a tax plan, it's a product of a team of policy experts, who know the terrain inside and out. But the reporter who has to file on deadline likely doesn't have any expertise on tax policy. So how can this coverage be anything but shallow?

And further, there's the additional problem that the longer reporters spend with a campaign, the more likely they'll develop either a kind of contempt for the candidate and the campaign or a strange version of the Stockholm syndrome. Clearly such was the case during 2000 and 2004, when reporters' dislike for Gore and Kerry was palpable. And while the response may be natural and human, it breeds awful journalism.

Structural Solutions

These structural flaws have solutions, and so I offer some humble recommendations:

- Rotate reporters. There's no reason to simply assign a reporter and have that person stay with a campaign for its duration. It's not like you need "expertise" to cover a campaign or that there's a steep learning curve. It's not a domain of knowledge or a proper beat. A competent reporter can parachute into a campaign and quickly get her bearings. For that reason, a paper such as The New York Times should just send a stringer to follow around candidates and file if something big happens or when news breaks. But reporters shouldn't have to be constantly filing dispatches about the daily minutiae of the trail. And those stringers should be rotated in and out, until perhaps the final leg of the campaign. I think if that were the setup, you wouldn't get stories about Kerry's "butler."

- Go for more features and less daily reporting. In fact, The New York Times has been doing this, though their feature coverage has focused on such burning issues as what Hillary Clinton wrote in letters to a pen pal 35 years ago. But the paper also produced an excellent piece about Giuliani's fraught relationship with New York City's black residents. These kinds of longer-form, nondeadline pieces are fun to read and far more informative than the daily dispatch.

- Assign campaign coverage to beat reporters, and this is key. When Obama released his tax plan, the article about it was authored by Obama beat reporter Jeff Zeleny. He is a perfectly good political reporter, and he's been following Obama since 2003, when he was writing for the Chicago Tribune, but there's no earthly reason to think he's well equipped to report on a tax plan. Meanwhile, the Times happens to have on staff the Pulitzer Prize-winning David Cay Johnston, who is unquestionably the single best tax reporter in the country. Why wouldn't he be assigned to write about Obama's tax plan — even in the first news reporting about it? The same goes for every substantive area of policy. The Washington Post and the Times have reporters who know a lot about environmental policy, health policy, fiscal policy, etc. Why not have them cover those aspects of the campaign?

My final suggestion likely won't be popular and, indeed, it might very well be impossible to implement, but I offer it nonetheless, because I think it's the single most essential way of improving coverage. As a young reporter I remember a wise editor telling me that the easiest way to make an article better was by cutting it by a third: trim the fat. The fundamental problem with campaign coverage is that there is too much of it.

A campaign is ultimately about the future of the nation and, indeed, in the case of our presidential election, the world. But the irony of a campaign season is that the contest itself often draws more attention than the underlying events — war, a housing crisis, recession — which are increasingly relegated to the inside pages. Cut a quarter of all campaign coverage and replace it with coverage of our nation's and the global economy, wars in which our troops are engaged (or one day might be), and the threats to our planet and ourselves. This would take us a long way towards curtailing our worst collective habits and impulses. It likely would not be great for the bottom line, but it sure would be good for the country.

Christopher Hayes, who has reported and written on politics, economics and labor since 2002, is the Washington, D.C. editor of The Nation. He adapted this article from words he wrote in The Nation on January 5, 2008 and from a blog entry entitled "Is Good Campaign Coverage Possible?" that he wrote on September 20, 2007.