Does the news simply exist, or is it constructed? For a long time many have believed that it existed, and all journalists needed were well-trained eyes to convey it to the public. To do this, techniques for how to describe and structure information were developed. Following these techniques, journalists could obtain similar results; indeed, for a long time press agencies and newspapers did not sign their stories because it did not matter who had written them. What mattered was the method used to do so. That era was ruled by the five W’s, a premade formula in the shape of an upside-down pyramid, and by rigid professional dogmas, such as the ban on subjectivity and the journalist’s perspective.

How does this focus limit knowledge of what really happens? Let’s take an example. In 2003, Spain experienced an unusual heat wave. One of its effects was a series of cases of senior citizens who, alone in their houses, died of dehydration or conditions worsened by the suffocating heat. Their bodies remained in their homes for several days until the smell of decomposition alerted their neighbors to the situation.

Using the traditional approach, the press presented the story in more or less the following way: “A senior citizen died of natural causes in his apartment last Saturday, possibly due to the high temperatures. Three days went by before, alarmed by the odor in the building, the neighbors discovered the body.” This version includes what happened, when it happened, how it happened, why it happened, where it happened, and to whom it happened. Yet it emphasizes the extraordinary—death—and ignores the “ordinary”—life.

If journalists had approached this information from another perspective, they would have revealed something different: For the unfortunate people (the dead seniors) it was much worse to live in solitude, without any vital connections, than to die in solitude. This was missing in the press accounts, however. Why?

Let’s imagine the following scenario: We are in an editing room and we receive a call from someone saying that the body of a senior citizen has been found in their building. What do we do? We send a reporter and a photographer to cover the story. Now imagine that another person calls and, when we pick up, we hear: “I am 80 years old, I feel lonely, I can barely breathe in this heat and I don’t have anyone to turn to.” Would we write a story about that person? Would we turn it into news? Or, more likely, would we give the caller the phone number of a social services agency and forget about it?

We return to the original question: Does news exist or is it constructed? This is not a mere epistemological question; it has major social effects. When stories about the deaths of senior citizens appeared, the Madrid city government sought a solution. What was that solution? Give every senior citizen who lived alone a beeper. As soon as the person began to feel unwell, he or she pressed a button on the beeper and an emergency operation to prevent him or her from dying alone was unleashed. Until then, however, the elderly man or woman was left alone.

In this case, it is worth asking whether journalism informed people about the core of the problem and helped them come up with a better solution. I believe the answer is no, not because we lacked desire or concern, but because we work with cognitive tools that are no longer useful.

Learning to Use New Tools

What new tools might give journalists better ways to approach coverage of current events? First, journalists would need tools to help them place current news in a historical context and let the protagonists’ voices be heard. This does not mean only conveying information (an elderly person dies due to the heat …) but rather telling a story (how the elderly who live alone feel, what their daily routines are like, what, if any, connections they have to life). The consequence— the solitary death—is not as important as what led up to it.

Neither can journalists exclude subjectivity when telling the story of the main players, the neighbors, the family, and the people who design social policy. In dealing with a topic like this one, the bare information says little or nothing. It is necessary to find out how the community assimilates, understands, accepts or rejects the process of making senior citizens into involuntary hermits. Furthermore, since the journalist might feel affected by an issue such as this one, why not also train him or her to communicate on the basis of what he or she perceives and feels?

Creating a space for this type of training in journalism is the idea that gave rise to the Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Periodismo Narrativo (Center for Advanced Studies in Narrative Journalism), which I now direct. Its main aim is to show journalists that the news doesn’t only exist but should be constructed.

During the two decades I was working in the leading media before opening the center, some colleagues and I detected a desire on the part of journalists to learn a new way of narrating their news coverage. The challenge was how to design an innovative, useful and sustainable approach. Above all, we wanted to provide a nonelitist space to which journalists from big cities and small towns could have access. We need good journalism in urban areas but also in distant provinces and regions, where highly concentrated power or quasi-feudal systems prevent the development of a vibrant civil life.

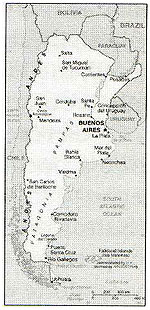

For these reasons, we designed an online alternative for Spanish-speaking journalists who work in large media and have access to training options, but also for journalists working for smaller media who often cannot afford to travel and pay for a course far from where they live. We developed a digital educational platform. This makes sense since interest in the work of this center has spread across a vast geographical area, from Mexico, and even into the United States, to the south of Argentina. And let’s not forget about Spain.

In online education it is essential to foster a sense of educational community. To do this, we make great use of the workshop format. Each journalist reads the text of the others and, in a specially designed chat room, discusses the strengths and weakness of each work during a weekly meeting. The professor also develops a personal relationship with each student via e-mail and, in addition, uploads scanned reading material to discuss in the next meeting.

Of the educational techniques that we use, there are three that we uphold firmly because they are essential to the success of the workshops.

While indispensable, this honesty can be surprising since writing as a paid journalist tends to be a space of scant contact with peers. It is common to talk to colleagues about things like the weather, kids, relationships, vacation spots, but not so much about work techniques that each person uses or how he perceives the other’s techniques. For obvious reasons, our workshops are carried out in a less competitive climate than that of a newsroom and, as a result, it is easier to encourage sharing.

Although the journalists who participate in our courses share the Spanish language, they have very different backgrounds. In one course, “The Informative Story,” for example, the online group of students includes Sara, a journalist from Barcelona, Spain who writes in both Catalan and Spanish; Adrián, who works for the newspaper “Río Negro,” published in the city of General Roca, Patagonia, Argentina; Augustin, a Mexican reporter for the Spanish-language newspaper “La Opinión” in Los Angeles, and Norberto, an Internet journalist from Panama City.

Differences Enhance the Learning Experience

What do they have in common? What separates them? Clearly, a shared language and a certain common historical background connect them. Yet some work in countries with high Gross Domestic Products and advanced political structures, whereas others are immersed in precarious institutional and economic realities. Some live in large cities (Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Madrid), while others work in small towns (Coronel Dorrego, Argentina and Ica, Peru).

These differences have not presented problems. We always assumed gaps would exist, and we have used them to positive ends. At the beginning of each workshop, we clarify that, in discussing the works, participants keep in mind the text itself but also its context. We ask this because there are topics, vocabulary and ways of narrating that might be too experimental in a given place and would keep people away rather than draw them in. When dealing with sources and research, journalists from the more developed regions and the large cities are more accustomed to demanding information and to invoking, if possible, the judicial system to protect their investigations. In smaller places, because people often know each other, the search for information is bound up in personal ties and complicities that can hinder fully uncovering the facts.

Differences between Latin America and Spain are also important. In the Americas, there is a more recent history of heated struggles for freedom of expression in newer democracies. (Indeed, some Latin American governments and “friendly” media sometimes try to stop the trend towards democracy.) In Spain, there is a sense of a stable democracy that allows for a free press. Being too comfortable, however, can sometimes generate a press that is little inclined to read between the lines or to investigate, and this can lead to a discourse overly reliant on official sources.

In our workshops, diversity is enriching. And we believe one strength of our approach is not encapsulating the journalist in an excessively homogenous setting, but rather placing him in one abundant in intellectual challenges. This approach varies, of course, when we are commissioned by a given news organization to do a workshop, but even then we try to deal with provocative situations.

All of the activities we engage in, including those we custom design for news groups and schools, place emphasis on narrative and defend the idea that even though facts might be objective, reality is a highly subjective web of those facts. Whether journalists feel comfortable in this role or not (and whether this role contradicts long-held theories of information gathering or not), they are the ones who give life to this reality. The journalist explains it, shows the evident and hidden links, roots those links in a history, and puts together the puzzle of a changing world to which we are often only mere witnesses.

This is where our obsession as educators lies—in encouraging a journalism that fosters a society in which fewer people look from the sidelines without understanding what is happening.

What Can This Accomplish?

Do we believe our work has real effects? Are media today—in an era when training is more highly valued than before—more independent? Do they cover reality more fully? Do they provide better information? I fear that the answers to these questions are complex and covered with a glint of skepticism.

If journalists ask for and often get training, why is the level of the media still unsatisfying?

We cannot give a thorough response to that question here, but we can offer a few clues. One of them is that the training offered, at least in our case, is for working journalists. Can these journalists make it alone in an environment that is sometimes adverse and that does not always appreciate their contributions? Perhaps, in the case of some journalists, there are media where other, not strictly informational, interests are at stake (corporate, commercial, ideological interests, for example). And we might also speak of difficult work situations, such as when, after years of working as a contributor, a person is finally promoted to staff writer and, wanting to keep this position, does not rock the boat.

These examples offer clues that might open up another query: Is training journalists enough? Or do we also have to address other social actors? Train politicians, for example, and remind them how important a challenging press is to preserving the system that they represent. Or alert media executives to the fact that privileging trivial information is like fireworks: They shine brightly but burn out quickly and leave us in the dark. Wouldn’t it also be worthwhile to consider improving the educational system and, starting at school, fortify a critical public?

In sum, in training journalists, they become capable of writing better stories and discerning what’s important more easily. It is a first step, and it is not a minor one. But perhaps a broader, more societal approach is necessary to foster a journalism that, above all, defends the idea of the mature, well-informed citizen who is close to the facts but also understands their causes.

Daniel Ulanovsky Sack, a 1996 Nieman Fellow, worked for the newspaper Clarín and was the executive editor of the magazine Latido. He directs the Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Periodismo Narrativo in Buenos Aires, Argentina (www.periodismonarrativo. com).

How does this focus limit knowledge of what really happens? Let’s take an example. In 2003, Spain experienced an unusual heat wave. One of its effects was a series of cases of senior citizens who, alone in their houses, died of dehydration or conditions worsened by the suffocating heat. Their bodies remained in their homes for several days until the smell of decomposition alerted their neighbors to the situation.

Using the traditional approach, the press presented the story in more or less the following way: “A senior citizen died of natural causes in his apartment last Saturday, possibly due to the high temperatures. Three days went by before, alarmed by the odor in the building, the neighbors discovered the body.” This version includes what happened, when it happened, how it happened, why it happened, where it happened, and to whom it happened. Yet it emphasizes the extraordinary—death—and ignores the “ordinary”—life.

If journalists had approached this information from another perspective, they would have revealed something different: For the unfortunate people (the dead seniors) it was much worse to live in solitude, without any vital connections, than to die in solitude. This was missing in the press accounts, however. Why?

Let’s imagine the following scenario: We are in an editing room and we receive a call from someone saying that the body of a senior citizen has been found in their building. What do we do? We send a reporter and a photographer to cover the story. Now imagine that another person calls and, when we pick up, we hear: “I am 80 years old, I feel lonely, I can barely breathe in this heat and I don’t have anyone to turn to.” Would we write a story about that person? Would we turn it into news? Or, more likely, would we give the caller the phone number of a social services agency and forget about it?

We return to the original question: Does news exist or is it constructed? This is not a mere epistemological question; it has major social effects. When stories about the deaths of senior citizens appeared, the Madrid city government sought a solution. What was that solution? Give every senior citizen who lived alone a beeper. As soon as the person began to feel unwell, he or she pressed a button on the beeper and an emergency operation to prevent him or her from dying alone was unleashed. Until then, however, the elderly man or woman was left alone.

In this case, it is worth asking whether journalism informed people about the core of the problem and helped them come up with a better solution. I believe the answer is no, not because we lacked desire or concern, but because we work with cognitive tools that are no longer useful.

Learning to Use New Tools

What new tools might give journalists better ways to approach coverage of current events? First, journalists would need tools to help them place current news in a historical context and let the protagonists’ voices be heard. This does not mean only conveying information (an elderly person dies due to the heat …) but rather telling a story (how the elderly who live alone feel, what their daily routines are like, what, if any, connections they have to life). The consequence— the solitary death—is not as important as what led up to it.

Neither can journalists exclude subjectivity when telling the story of the main players, the neighbors, the family, and the people who design social policy. In dealing with a topic like this one, the bare information says little or nothing. It is necessary to find out how the community assimilates, understands, accepts or rejects the process of making senior citizens into involuntary hermits. Furthermore, since the journalist might feel affected by an issue such as this one, why not also train him or her to communicate on the basis of what he or she perceives and feels?

Creating a space for this type of training in journalism is the idea that gave rise to the Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Periodismo Narrativo (Center for Advanced Studies in Narrative Journalism), which I now direct. Its main aim is to show journalists that the news doesn’t only exist but should be constructed.

During the two decades I was working in the leading media before opening the center, some colleagues and I detected a desire on the part of journalists to learn a new way of narrating their news coverage. The challenge was how to design an innovative, useful and sustainable approach. Above all, we wanted to provide a nonelitist space to which journalists from big cities and small towns could have access. We need good journalism in urban areas but also in distant provinces and regions, where highly concentrated power or quasi-feudal systems prevent the development of a vibrant civil life.

For these reasons, we designed an online alternative for Spanish-speaking journalists who work in large media and have access to training options, but also for journalists working for smaller media who often cannot afford to travel and pay for a course far from where they live. We developed a digital educational platform. This makes sense since interest in the work of this center has spread across a vast geographical area, from Mexico, and even into the United States, to the south of Argentina. And let’s not forget about Spain.

In online education it is essential to foster a sense of educational community. To do this, we make great use of the workshop format. Each journalist reads the text of the others and, in a specially designed chat room, discusses the strengths and weakness of each work during a weekly meeting. The professor also develops a personal relationship with each student via e-mail and, in addition, uploads scanned reading material to discuss in the next meeting.

Of the educational techniques that we use, there are three that we uphold firmly because they are essential to the success of the workshops.

- Write an article each week using a specific guideline.

- Read the work of participants and be prepared to comment on it.

- Exhibit great honesty in the critiques.

While indispensable, this honesty can be surprising since writing as a paid journalist tends to be a space of scant contact with peers. It is common to talk to colleagues about things like the weather, kids, relationships, vacation spots, but not so much about work techniques that each person uses or how he perceives the other’s techniques. For obvious reasons, our workshops are carried out in a less competitive climate than that of a newsroom and, as a result, it is easier to encourage sharing.

Although the journalists who participate in our courses share the Spanish language, they have very different backgrounds. In one course, “The Informative Story,” for example, the online group of students includes Sara, a journalist from Barcelona, Spain who writes in both Catalan and Spanish; Adrián, who works for the newspaper “Río Negro,” published in the city of General Roca, Patagonia, Argentina; Augustin, a Mexican reporter for the Spanish-language newspaper “La Opinión” in Los Angeles, and Norberto, an Internet journalist from Panama City.

Differences Enhance the Learning Experience

What do they have in common? What separates them? Clearly, a shared language and a certain common historical background connect them. Yet some work in countries with high Gross Domestic Products and advanced political structures, whereas others are immersed in precarious institutional and economic realities. Some live in large cities (Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Madrid), while others work in small towns (Coronel Dorrego, Argentina and Ica, Peru).

These differences have not presented problems. We always assumed gaps would exist, and we have used them to positive ends. At the beginning of each workshop, we clarify that, in discussing the works, participants keep in mind the text itself but also its context. We ask this because there are topics, vocabulary and ways of narrating that might be too experimental in a given place and would keep people away rather than draw them in. When dealing with sources and research, journalists from the more developed regions and the large cities are more accustomed to demanding information and to invoking, if possible, the judicial system to protect their investigations. In smaller places, because people often know each other, the search for information is bound up in personal ties and complicities that can hinder fully uncovering the facts.

Differences between Latin America and Spain are also important. In the Americas, there is a more recent history of heated struggles for freedom of expression in newer democracies. (Indeed, some Latin American governments and “friendly” media sometimes try to stop the trend towards democracy.) In Spain, there is a sense of a stable democracy that allows for a free press. Being too comfortable, however, can sometimes generate a press that is little inclined to read between the lines or to investigate, and this can lead to a discourse overly reliant on official sources.

In our workshops, diversity is enriching. And we believe one strength of our approach is not encapsulating the journalist in an excessively homogenous setting, but rather placing him in one abundant in intellectual challenges. This approach varies, of course, when we are commissioned by a given news organization to do a workshop, but even then we try to deal with provocative situations.

All of the activities we engage in, including those we custom design for news groups and schools, place emphasis on narrative and defend the idea that even though facts might be objective, reality is a highly subjective web of those facts. Whether journalists feel comfortable in this role or not (and whether this role contradicts long-held theories of information gathering or not), they are the ones who give life to this reality. The journalist explains it, shows the evident and hidden links, roots those links in a history, and puts together the puzzle of a changing world to which we are often only mere witnesses.

This is where our obsession as educators lies—in encouraging a journalism that fosters a society in which fewer people look from the sidelines without understanding what is happening.

What Can This Accomplish?

Do we believe our work has real effects? Are media today—in an era when training is more highly valued than before—more independent? Do they cover reality more fully? Do they provide better information? I fear that the answers to these questions are complex and covered with a glint of skepticism.

If journalists ask for and often get training, why is the level of the media still unsatisfying?

We cannot give a thorough response to that question here, but we can offer a few clues. One of them is that the training offered, at least in our case, is for working journalists. Can these journalists make it alone in an environment that is sometimes adverse and that does not always appreciate their contributions? Perhaps, in the case of some journalists, there are media where other, not strictly informational, interests are at stake (corporate, commercial, ideological interests, for example). And we might also speak of difficult work situations, such as when, after years of working as a contributor, a person is finally promoted to staff writer and, wanting to keep this position, does not rock the boat.

These examples offer clues that might open up another query: Is training journalists enough? Or do we also have to address other social actors? Train politicians, for example, and remind them how important a challenging press is to preserving the system that they represent. Or alert media executives to the fact that privileging trivial information is like fireworks: They shine brightly but burn out quickly and leave us in the dark. Wouldn’t it also be worthwhile to consider improving the educational system and, starting at school, fortify a critical public?

In sum, in training journalists, they become capable of writing better stories and discerning what’s important more easily. It is a first step, and it is not a minor one. But perhaps a broader, more societal approach is necessary to foster a journalism that, above all, defends the idea of the mature, well-informed citizen who is close to the facts but also understands their causes.

Daniel Ulanovsky Sack, a 1996 Nieman Fellow, worked for the newspaper Clarín and was the executive editor of the magazine Latido. He directs the Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Periodismo Narrativo in Buenos Aires, Argentina (www.periodismonarrativo. com).