Whitney Dow and Marco Williams directed and produced “Two Towns of Jasper,” a film broadcast this year as part of the P.O.V. series on the Public Broadcasting Service. In the article that follows, Dow and Williams create a dialogue of questions and answers to explain how and why they divided their reporting along racial lines to document a racial hate crime in the small Texas town of Jasper. In the opening section—as they speak of themselves in the third person—they describe how their project began.

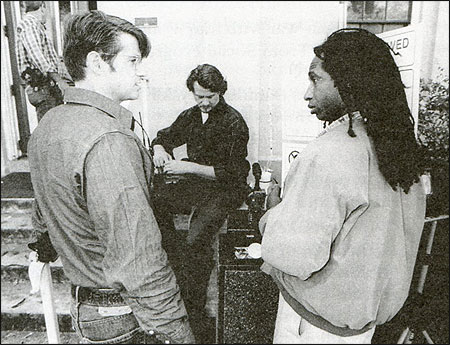

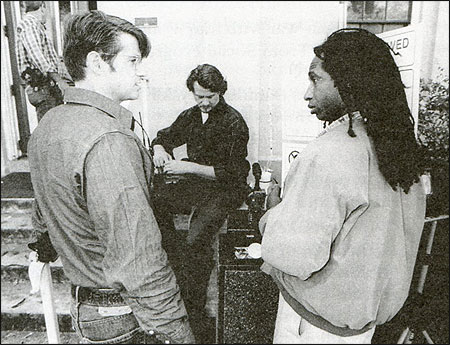

Codirectors Whitney Dow (left) and Marco Williams (right) outside the Jasper, Texas county courthouse. Photo by Danny Bright.

How It Began

On June 7, 1998, perhaps the most vicious, racially motivated murder since the 1955 lynching of Emmett Till occurred in Jasper, Texas. In the early hours of the morning, James Byrd, Jr., an African American, was beaten, then chained to the back of a pick-up truck and dragged for three miles until his body disintegrated and his head was decapitated by a roadside culvert. Three white men from Jasper—John William King, Lawrence Russell Brewer, and Shawn Allen Berry—were arrested for kidnap and murder.

In the days following the murder, Whitney Dow called Marco Williams, his friend of over 20 years. As the two spoke about the murder, they both expressed dismay, shock and outrage at the crime. However, Marco (who is black) did not share Whitney’s (who is white) surprise that so brutal an act, one motivated by race, could occur in the last half of the last decade of the 20th century. Over the course of the next three months, race continued to serve as a catalyst in their discussions, and Whitney and Marco decided to create a documentary on the events in Jasper and the subsequent trials of the three men accused of killing Byrd.

With the perception divide being a recurrent theme in their talks, they concluded that the best and, in fact, the only logical way to document the town where James Byrd was murdered, was by using segregated crews. Subsequently, Marco spent a year in Jasper with a black crew talking with and filming only black people, while Whitney spent that same year with white people and a white crew. The resulting film is “Two Towns of Jasper.”

To tap into their experiences and what they learned, Marco and Whitney pose and respond to questions they’ve been asked—and questions they asked themselves—about the difficulty and benefits of using this approach in the coverage of stories about race.

Discussing the Shawn Allen Berry murder trial over breakfast at the Belle-Jim Hotel, Jasper, Texas. Photo by Danny Bright.

The Technique

Can a white reporter cover stories in black communities and arrive at “the truth” and vice versa?

Whitney Dow: Can journalists work effectively across race? Absolutely, but I now believe that blacks and whites will necessarily file fundamentally different stories when they cover racially charged events. During the research phase of this project, I spent some time in Jasper immediately following the murder of Byrd interviewing both white and black residents. At the time, I got what I thought were some valuable interviews with some of the black residents. Later, when we began filming the project in earnest and Marco spent time filming some of these same black residents, something startling was revealed: Many of the people I’d interviewed deliberately misled me about their identity, occupation, place of residence, etc. Although blacks were willing to talk to me about the murder and the problems that existed in their community, they were unwilling to reveal anything that might put themselves at risk. This called into question the value of the interviews I had done and revealed the baseline of distrust that colors almost all interaction across race.

At the same time, I cannot imagine I could have gained the same level of trust of the white community and, more specifically, of the family members of the accused killers, if I had an African American on my production team. The whites were so focused on their desire to present a positive image of race relations to the media that many times during the initial phase of a relationship with a documentary subject I felt as though I was being subjected to a P.R. blitz. It took time for the white residents to let down their guard and begin to speak honestly about their feelings. Having a black person there would have been a constant reminder to keep themselves in check.

Marco Williams: Why are we intimidated, if not outright afraid, of the idea of utilizing racially specific reporters to cover a racially specific type of story and to help uncover the “truth”? In most newsrooms, specialization of reporting is practiced daily: sports reporters cover sports, business reporters business, fashion reporters fashion. Such assignments are rarely questioned. But when a racially motivated murder occurs, some challenge the idea of reporting or documenting this story with “specialists” or, as others contend, it exacerbates the problem. In covering a news event or telling a story, “truth” often seems determined by who is privileged to narrate the coverage, choose the angle, identify the protagonists, and determine the questions to be asked. These decisions are not random or in any way “natural” choices. Each reporter, each documentary filmmaker, each witness brings to the situation a set of biases and perceptions that arise out of who they are and what has been their personal, cultural and social history. If the “truth” of a story could be defined before reporting or documenting is done, then who defines the “truth” becomes critical to understanding the events and putting them into a larger context.

Perhaps, therefore, it is foolhardy to pursue the “truth.” Instead, our goal can be understanding. But there is a difference between explaining and sharing an experience. Sharing relies on having a common ground of experience and understanding, which is often not the case for black and white people in America. (Think O.J. Simpson verdict.) This is why Whitney and I determined that the best way to arrive at a truthful understanding of Jasper, and by extension America, was to use segregated film crews. This would give people the space to speak freely—out of their experience and understanding—and then allow us to bring these voices and viewpoints together to tell the events through black and white lenses.

In the case of race, where division often lurks, arriving at “truth” is more likely to happen when we embrace our differences through the embrace of our commonalities.

Huff Creek Road, where James Byrd, Jr., was murdered. Photo by Steven Miller.

The Edit

Was it hard to knit our two perspectives into one film?

Whitney: The difficulty of weaving Marco’s and my footage into a single narrative was not that the white and black residents of Jasper saw things differently—it was that they saw and experienced entirely different things. Events important to the white community were often not even on the black community’s radar screen, and vice versa. An example of this was discussion of James Byrd’s character. For the whites, their understanding of the murder was inexorably tied to their perception of James Byrd, the man. Many whites felt that the fact that Byrd was unemployed and had many past run-ins with the law either mitigated the gravity of the crime or somehow implicated Byrd in his own death. They felt he should be “judged by the way he lived not the way he died” and were uncomfortable with any positive coverage he got in the media.

For blacks, how James Byrd lived his life was entirely irrelevant. He was killed because of his race and so, in effect, they were James Byrd. After putting together a scene in which whites discussed Byrd’s background, I expected Marco to have footage that would speak to the same subject. In fact, he had no one discussing Byrd’s character because it was not an issue in the black community. This scenario was repeated again and again. What we discovered was that much of the time the scenes we created explicated specific periods of time, rather than specific events.

Marco: In the making of “Two Towns of Jasper,” Whitney and I effectively shot two different movies. In editing, we had to figure out how to make one. This demanded a relinquishing of absolute power and a movement toward shared power. In the framework of collaborative decision-making, is this possible? In the context of race, is this possible?

Who defines the context of a given scene or the order of the story is an assertion of power. No decision is simply an aesthetic choice. Who speaks first or last in a given sequence is of subtle if not overt significance. Struggles about this power played themselves out repeatedly in the editing room. The sequence about the school board’s decision to temporarily eliminate Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday as a school holiday provides a potent illumination of both the nature of the fabric of the town and of the impact that race had on the decision-making in the editing room. Just trying to arrive at an order that satisfied a sense of narrative, let alone a sense of theme and content, was problematic. Black and white residents saw the decision to remove the holiday very differently. So did Whitney and I.

Who should speak about this incident? What should this decision reveal about individual characters? About the town? We debated, too, whether the sequence or its placement detoured from the linear narrative of three murder trials. But where our debate lingered the longest was in deciding whose words (whose image) should end this section of the film.

Should it end with the radio reporter Mike Lout? He tells us that the holiday isn’t important to him because he never had to sit in the back of the bus; he tells us, with a nervous laugh, that whites won’t ever do that to black people again. Or should it end with the minister Ray Lewis? Ray tells us that “they” must have thought that “we” weren’t going to say or do anything, as we didn’t in the past; he also expresses some disconcertedness by the questioning of how the school board could consider doing this with all that had been going on.

Ending with Mike provides an articulation of the holiday’s lack of significance to whites, as well as an unambiguous feeling of guilt. Ending with Ray provides an illumination of the state of black power in the town, the ability or inability to say or to do something. And his words reveal the fissure between black and white. Is Martin Luther King, Jr. day a black holiday or an American holiday? Either ending has validity, but in a film as tightly woven as “Two Towns of Jasper,” what is said last is likely to be what viewers remember.

The recognition that power is embedded in the storytelling played out repeatedly in the editing room. In a film that struggles to make vivid the differing perceptions of blacks and whites, what the audience retains is crucial.

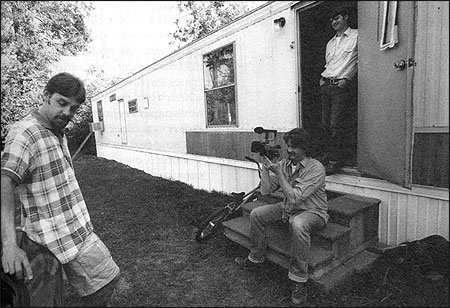

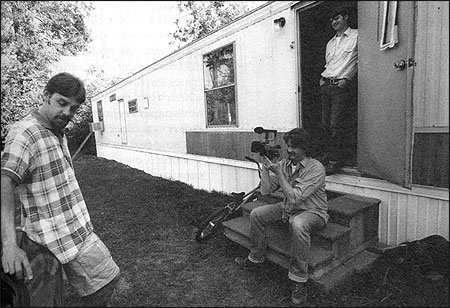

Trent Smith (left), Director of Photography Steven Miller, and Whitney Dow (right) at Smith’s home in Jasper. Photo by Danny Bright.

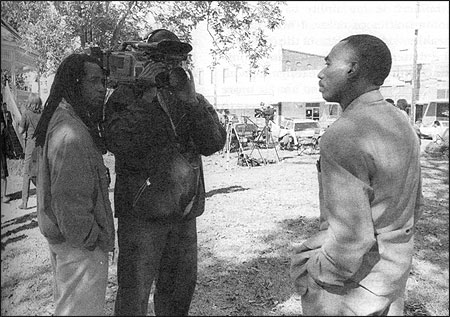

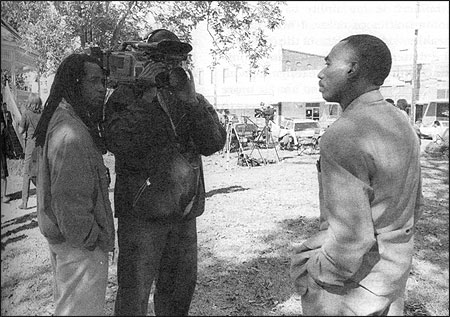

Marco Williams (left) and Director of Photography Jonathan Weaver with Rev. Ray Lewis (right) in Jasper. Photo by Danny Bright.

Our Differences

Were there times when our two viewpoints were irreconcilable?

Whitney: Our goal of having white and black viewpoints represented in almost every sequence was a major challenge. But our attempt to include a visit to Jasper by the New Black Panther Party during the trial of John William King proved particularly difficult. It was impossible for us to cut a sequence in which neither the whites looked afraid—which they were not—nor the blacks looked weak—which also was not the case. The scene structure we settled on was dissatisfying to each of us, and this entire sequence was cut from the film when we reedited it for broadcast on PBS. This was an exception. Though we initially disagreed on how most scenes should be structured, we managed to find ways of melding our opposing viewpoints. This method of working yielded much more complex and compelling sequences than either of us could have constructed on our own.

Marco: To take on the challenge of questioning race relations, whether within or across the boundaries of race, is not without potential casualty. The scene with the New Black Panther Party offers a good illustration of what can happen when the perception and meaning of an event is not shared. In the festival and the theatrical version of our film, we included the New Black Panther Party. But we omitted them from the television version. Why? The simple answer is that the New Black Panther Party did not fit into the narrative. More complicated are the differing reasons we had for its removal. Whitney saw them as outsiders to the community and therefore not fitting into the framework of our film—the inclusion of residents of Jasper. I judged this scene expendable because although the New Black Panther Party’s entrance into the film is clear, its eventual disappearance is not explained.

However, beneath concerns for the narrative justification there lurks a more profound difference of what the New Black Panther Party represents for Whitney and me and for white and black residents of Jasper. For Whitney (serving as proxy for whites), the New Black Panther Party was seen as a joke, not threatening, and no white resident took them seriously. For me, (a proxy for the blacks), its members represented “manhood,” power and the conflict of confrontation vs. reconciliation that blacks have wrestled with throughout our history in the United States. In the face of such broad differences, compromise or accommodation was required. When the debate could not be reconciled, the exigencies of narrative became the ultimate basis of our decision-making.

James Byrd, Jr.’s sister, Mary Verrett, after Shawn Berry’s testimony. Jasper, Texas, 1999. Photo by Danny Bright.

Lessons Learned

Whitney: It is easy to forget, as a liberal white journalist covering issues of race, that to many people I come in contact with in my reporting I represent a power structure that repeatedly has shown itself to be inherently untrustworthy and, at times, even dangerous to people of color. Although I am still extremely confident in my ability to penetrate communities of color, I now have a healthy skepticism about the quality of the material and information I come away with and am more diligent about checking sources. I also am far more aware of my biases, even as I attempt to be “objective” in my coverage, and I try to use this awareness as a tool to help me become a better storyteller.

Marco: Whitney and I experienced what few experience on the battleground of race in America: We asked questions about race on a daily basis for four-and-a-half years. What I learned in making “Two Towns of Jasper” was how crucial ownership of my reality is to changing the relationship between black and white. When differing viewpoints in a debate have equal footing, then and only then can fruitful understanding be achieved.

It should not disturb us to realize that those who don’t share a history could have different interpretations and understanding of the same event. When James Byrd was murdered, the way in which white (or mainstream) and black newspapers reported the news was as different as black and white. This should not surprise us.

Future events will polarize Americans, and we should be able to accept and embrace that which polarizes us, rather than avoiding or ignoring what divides. Differences need to become part of our discourse. Who interprets an event, who gets to report on stories that shape our collective histories, who has the chance to define the “truth”—all of these decisions are important in shaping our understanding of events and how events are interpreted. Ultimately, how they are reported and recorded is crucial to giving us a basis to think about and perhaps understand how they could have occurred.

Marco Williams is an award-winning documentary and fiction film director. His films include “Two Towns of Jasper,” “In Search of our Fathers,” “From Harlem to Harvard,” and “Without a Pass.” His 1998 film “Making Peace: Rebuilding Our Communities” was part of a four-hour PBS series profiling people working to heal the conditions that create violence in their communities. Whitney Dow directed more than 200 commercial film and commercial projects before he was asked to direct two documentary shorts for the American AIDS Rides in 1997. In 1998, he created Feral Films to pursue documentary filmmaking full-time, and “Two Towns of Jasper” became his first feature documentary.

Codirectors Whitney Dow (left) and Marco Williams (right) outside the Jasper, Texas county courthouse. Photo by Danny Bright.

How It Began

On June 7, 1998, perhaps the most vicious, racially motivated murder since the 1955 lynching of Emmett Till occurred in Jasper, Texas. In the early hours of the morning, James Byrd, Jr., an African American, was beaten, then chained to the back of a pick-up truck and dragged for three miles until his body disintegrated and his head was decapitated by a roadside culvert. Three white men from Jasper—John William King, Lawrence Russell Brewer, and Shawn Allen Berry—were arrested for kidnap and murder.

In the days following the murder, Whitney Dow called Marco Williams, his friend of over 20 years. As the two spoke about the murder, they both expressed dismay, shock and outrage at the crime. However, Marco (who is black) did not share Whitney’s (who is white) surprise that so brutal an act, one motivated by race, could occur in the last half of the last decade of the 20th century. Over the course of the next three months, race continued to serve as a catalyst in their discussions, and Whitney and Marco decided to create a documentary on the events in Jasper and the subsequent trials of the three men accused of killing Byrd.

With the perception divide being a recurrent theme in their talks, they concluded that the best and, in fact, the only logical way to document the town where James Byrd was murdered, was by using segregated crews. Subsequently, Marco spent a year in Jasper with a black crew talking with and filming only black people, while Whitney spent that same year with white people and a white crew. The resulting film is “Two Towns of Jasper.”

To tap into their experiences and what they learned, Marco and Whitney pose and respond to questions they’ve been asked—and questions they asked themselves—about the difficulty and benefits of using this approach in the coverage of stories about race.

Discussing the Shawn Allen Berry murder trial over breakfast at the Belle-Jim Hotel, Jasper, Texas. Photo by Danny Bright.

The Technique

Can a white reporter cover stories in black communities and arrive at “the truth” and vice versa?

Whitney Dow: Can journalists work effectively across race? Absolutely, but I now believe that blacks and whites will necessarily file fundamentally different stories when they cover racially charged events. During the research phase of this project, I spent some time in Jasper immediately following the murder of Byrd interviewing both white and black residents. At the time, I got what I thought were some valuable interviews with some of the black residents. Later, when we began filming the project in earnest and Marco spent time filming some of these same black residents, something startling was revealed: Many of the people I’d interviewed deliberately misled me about their identity, occupation, place of residence, etc. Although blacks were willing to talk to me about the murder and the problems that existed in their community, they were unwilling to reveal anything that might put themselves at risk. This called into question the value of the interviews I had done and revealed the baseline of distrust that colors almost all interaction across race.

At the same time, I cannot imagine I could have gained the same level of trust of the white community and, more specifically, of the family members of the accused killers, if I had an African American on my production team. The whites were so focused on their desire to present a positive image of race relations to the media that many times during the initial phase of a relationship with a documentary subject I felt as though I was being subjected to a P.R. blitz. It took time for the white residents to let down their guard and begin to speak honestly about their feelings. Having a black person there would have been a constant reminder to keep themselves in check.

Marco Williams: Why are we intimidated, if not outright afraid, of the idea of utilizing racially specific reporters to cover a racially specific type of story and to help uncover the “truth”? In most newsrooms, specialization of reporting is practiced daily: sports reporters cover sports, business reporters business, fashion reporters fashion. Such assignments are rarely questioned. But when a racially motivated murder occurs, some challenge the idea of reporting or documenting this story with “specialists” or, as others contend, it exacerbates the problem. In covering a news event or telling a story, “truth” often seems determined by who is privileged to narrate the coverage, choose the angle, identify the protagonists, and determine the questions to be asked. These decisions are not random or in any way “natural” choices. Each reporter, each documentary filmmaker, each witness brings to the situation a set of biases and perceptions that arise out of who they are and what has been their personal, cultural and social history. If the “truth” of a story could be defined before reporting or documenting is done, then who defines the “truth” becomes critical to understanding the events and putting them into a larger context.

Perhaps, therefore, it is foolhardy to pursue the “truth.” Instead, our goal can be understanding. But there is a difference between explaining and sharing an experience. Sharing relies on having a common ground of experience and understanding, which is often not the case for black and white people in America. (Think O.J. Simpson verdict.) This is why Whitney and I determined that the best way to arrive at a truthful understanding of Jasper, and by extension America, was to use segregated film crews. This would give people the space to speak freely—out of their experience and understanding—and then allow us to bring these voices and viewpoints together to tell the events through black and white lenses.

In the case of race, where division often lurks, arriving at “truth” is more likely to happen when we embrace our differences through the embrace of our commonalities.

Huff Creek Road, where James Byrd, Jr., was murdered. Photo by Steven Miller.

The Edit

Was it hard to knit our two perspectives into one film?

Whitney: The difficulty of weaving Marco’s and my footage into a single narrative was not that the white and black residents of Jasper saw things differently—it was that they saw and experienced entirely different things. Events important to the white community were often not even on the black community’s radar screen, and vice versa. An example of this was discussion of James Byrd’s character. For the whites, their understanding of the murder was inexorably tied to their perception of James Byrd, the man. Many whites felt that the fact that Byrd was unemployed and had many past run-ins with the law either mitigated the gravity of the crime or somehow implicated Byrd in his own death. They felt he should be “judged by the way he lived not the way he died” and were uncomfortable with any positive coverage he got in the media.

For blacks, how James Byrd lived his life was entirely irrelevant. He was killed because of his race and so, in effect, they were James Byrd. After putting together a scene in which whites discussed Byrd’s background, I expected Marco to have footage that would speak to the same subject. In fact, he had no one discussing Byrd’s character because it was not an issue in the black community. This scenario was repeated again and again. What we discovered was that much of the time the scenes we created explicated specific periods of time, rather than specific events.

Marco: In the making of “Two Towns of Jasper,” Whitney and I effectively shot two different movies. In editing, we had to figure out how to make one. This demanded a relinquishing of absolute power and a movement toward shared power. In the framework of collaborative decision-making, is this possible? In the context of race, is this possible?

Who defines the context of a given scene or the order of the story is an assertion of power. No decision is simply an aesthetic choice. Who speaks first or last in a given sequence is of subtle if not overt significance. Struggles about this power played themselves out repeatedly in the editing room. The sequence about the school board’s decision to temporarily eliminate Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday as a school holiday provides a potent illumination of both the nature of the fabric of the town and of the impact that race had on the decision-making in the editing room. Just trying to arrive at an order that satisfied a sense of narrative, let alone a sense of theme and content, was problematic. Black and white residents saw the decision to remove the holiday very differently. So did Whitney and I.

Who should speak about this incident? What should this decision reveal about individual characters? About the town? We debated, too, whether the sequence or its placement detoured from the linear narrative of three murder trials. But where our debate lingered the longest was in deciding whose words (whose image) should end this section of the film.

Should it end with the radio reporter Mike Lout? He tells us that the holiday isn’t important to him because he never had to sit in the back of the bus; he tells us, with a nervous laugh, that whites won’t ever do that to black people again. Or should it end with the minister Ray Lewis? Ray tells us that “they” must have thought that “we” weren’t going to say or do anything, as we didn’t in the past; he also expresses some disconcertedness by the questioning of how the school board could consider doing this with all that had been going on.

Ending with Mike provides an articulation of the holiday’s lack of significance to whites, as well as an unambiguous feeling of guilt. Ending with Ray provides an illumination of the state of black power in the town, the ability or inability to say or to do something. And his words reveal the fissure between black and white. Is Martin Luther King, Jr. day a black holiday or an American holiday? Either ending has validity, but in a film as tightly woven as “Two Towns of Jasper,” what is said last is likely to be what viewers remember.

The recognition that power is embedded in the storytelling played out repeatedly in the editing room. In a film that struggles to make vivid the differing perceptions of blacks and whites, what the audience retains is crucial.

Trent Smith (left), Director of Photography Steven Miller, and Whitney Dow (right) at Smith’s home in Jasper. Photo by Danny Bright.

Marco Williams (left) and Director of Photography Jonathan Weaver with Rev. Ray Lewis (right) in Jasper. Photo by Danny Bright.

Our Differences

Were there times when our two viewpoints were irreconcilable?

Whitney: Our goal of having white and black viewpoints represented in almost every sequence was a major challenge. But our attempt to include a visit to Jasper by the New Black Panther Party during the trial of John William King proved particularly difficult. It was impossible for us to cut a sequence in which neither the whites looked afraid—which they were not—nor the blacks looked weak—which also was not the case. The scene structure we settled on was dissatisfying to each of us, and this entire sequence was cut from the film when we reedited it for broadcast on PBS. This was an exception. Though we initially disagreed on how most scenes should be structured, we managed to find ways of melding our opposing viewpoints. This method of working yielded much more complex and compelling sequences than either of us could have constructed on our own.

Marco: To take on the challenge of questioning race relations, whether within or across the boundaries of race, is not without potential casualty. The scene with the New Black Panther Party offers a good illustration of what can happen when the perception and meaning of an event is not shared. In the festival and the theatrical version of our film, we included the New Black Panther Party. But we omitted them from the television version. Why? The simple answer is that the New Black Panther Party did not fit into the narrative. More complicated are the differing reasons we had for its removal. Whitney saw them as outsiders to the community and therefore not fitting into the framework of our film—the inclusion of residents of Jasper. I judged this scene expendable because although the New Black Panther Party’s entrance into the film is clear, its eventual disappearance is not explained.

However, beneath concerns for the narrative justification there lurks a more profound difference of what the New Black Panther Party represents for Whitney and me and for white and black residents of Jasper. For Whitney (serving as proxy for whites), the New Black Panther Party was seen as a joke, not threatening, and no white resident took them seriously. For me, (a proxy for the blacks), its members represented “manhood,” power and the conflict of confrontation vs. reconciliation that blacks have wrestled with throughout our history in the United States. In the face of such broad differences, compromise or accommodation was required. When the debate could not be reconciled, the exigencies of narrative became the ultimate basis of our decision-making.

James Byrd, Jr.’s sister, Mary Verrett, after Shawn Berry’s testimony. Jasper, Texas, 1999. Photo by Danny Bright.

Lessons Learned

Whitney: It is easy to forget, as a liberal white journalist covering issues of race, that to many people I come in contact with in my reporting I represent a power structure that repeatedly has shown itself to be inherently untrustworthy and, at times, even dangerous to people of color. Although I am still extremely confident in my ability to penetrate communities of color, I now have a healthy skepticism about the quality of the material and information I come away with and am more diligent about checking sources. I also am far more aware of my biases, even as I attempt to be “objective” in my coverage, and I try to use this awareness as a tool to help me become a better storyteller.

Marco: Whitney and I experienced what few experience on the battleground of race in America: We asked questions about race on a daily basis for four-and-a-half years. What I learned in making “Two Towns of Jasper” was how crucial ownership of my reality is to changing the relationship between black and white. When differing viewpoints in a debate have equal footing, then and only then can fruitful understanding be achieved.

It should not disturb us to realize that those who don’t share a history could have different interpretations and understanding of the same event. When James Byrd was murdered, the way in which white (or mainstream) and black newspapers reported the news was as different as black and white. This should not surprise us.

Future events will polarize Americans, and we should be able to accept and embrace that which polarizes us, rather than avoiding or ignoring what divides. Differences need to become part of our discourse. Who interprets an event, who gets to report on stories that shape our collective histories, who has the chance to define the “truth”—all of these decisions are important in shaping our understanding of events and how events are interpreted. Ultimately, how they are reported and recorded is crucial to giving us a basis to think about and perhaps understand how they could have occurred.

Marco Williams is an award-winning documentary and fiction film director. His films include “Two Towns of Jasper,” “In Search of our Fathers,” “From Harlem to Harvard,” and “Without a Pass.” His 1998 film “Making Peace: Rebuilding Our Communities” was part of a four-hour PBS series profiling people working to heal the conditions that create violence in their communities. Whitney Dow directed more than 200 commercial film and commercial projects before he was asked to direct two documentary shorts for the American AIDS Rides in 1997. In 1998, he created Feral Films to pursue documentary filmmaking full-time, and “Two Towns of Jasper” became his first feature documentary.