Do national reporters covering the presidential campaign and local reporters assigned to congressional races approach their work with the same journalistic values and assumptions? Are their reporting techniques similar? Which approach serves their readers better? Three members of the department of communication at Stanford University attempted to learn answers to these questions. Shanto Iyengar, the Chandler professor in communication, teaches courses on mass media and political campaigns. William F. Woo, former editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, teaches in the graduate journalism program. Jennifer McGrady is a doctoral student and research assistant in the department’s political communication laboratory and at the Center for Deliberative Democracy. The following article, composed by the three of them, explains what they learned in surveying newspaper reporters and editors about their political coverage.

By the middle of January, the 2004 campaign horserace was in full swing. In just a few days, the Iowa caucuses would select the nation’s first presidential delegates. In less than two weeks, New Hampshire would hold the first presidential primary. On February 3rd, seven more states would hold their primaries. Never had so many votes been cast so early, and never had they been so important in selecting a party’s presidential candidate.

While poll results are the most obvious manifestations of horserace coverage, the term also can include stories about the candidates’ strategies and fundraising, predictions of who will and will not turn out to vote, and other “nonsubstantive” topics that do not bring to citizens the information they need to make informed voting decisions. On the other hand, stories linking vital policy issues to candidates’ positions, competence and experience, as well as articles taking readers beyond the daily polling or the insider’s analysis of the campaign, provide the kind of substance voters need.

Horserace journalism has long been criticized—by those who practice it and by academic observers and even news consumers—but there is no denying its appeal on a number of levels. Such reporting produces fresh stories whenever a new poll is released, and it is cheap and easy to do. The “scientific method” of political polling also makes such coverage relatively immune to criticisms of bias. Moreover, by conducting polls, news companies offer powerful incentives for this horserace approach. During the 2004 political campaigns, CNN collaborated with Time to conduct polls; NBC News linked up with The Wall Street Journal; The New York Times with CBS News, and The Washington Post with ABC News. Journalists might grumble about the fixation on polls, but results from them are showcased by the nation’s most prestigious news outlets.

As the caucus and primary voting began, the polls were in alignment. The Democratic frontrunner was former Vermont Governor Howard Dean. CNN-Time and CBS-The New York Times placed Senator John Kerry, who would emerge as the candidate, fourth.

Examining the Coverage

We decided to take a close look at the techniques of election reporting as they would play out during the rest of the campaign. We brought to this task our varied perspectives of a political scientist, newspaper editor, and campaign researcher. We believed that in comparing techniques, assumptions and approaches of presidential campaign journalists with those of local reporters assigned to congressional races we might unearth some important differences. Among the questions we wanted to consider were the following:

RELATED ARTICLE

"Winning By Just Losing Less Badly; Edwards Visits Lima to Nibble at GOP"

- Stephen Koff In all, 101 reporters and editors representing 37 papers from every region of the country shared their thoughts and practices with us in an online survey. (To recruit these participants, we contacted managing or executive editors and asked for permission to approach the reporters and section editors responsible for election coverage. We invited 161 journalists to participate in our survey, of whom 101 agreed—a response rate of 63 percent.) Correspondents from major national newspapers agreed to discuss their coverage of the presidential race; for congressional races we reached out to local and regional newspapers whose circulation areas included districts where races were considered competitive. (National reporters received a slightly different version of our questionnaire than did local reporters; editors from both national and local papers received an identical third version.)

To compare what journalists said to what they did, we examined—through LexisNexis searches and by subscription—a selection of national and regional newspapers on a daily basis for the two weeks leading up to Election Day, November 2, 2004. The smallest of the papers had a circulation of 12,704, the largest more than two million. Because many of the editors and reporters were too busy to complete a lengthy questionnaire while the campaigns were in progress, the survey went out on November 10th.

We have divided our findings into two categories.

This second category of findings surfaced when we noticed that in many instances the coverage we read reflected neither the news values nor production processes that the journalists reported following. For example, on a scale of one (focused entirely on horserace coverage) to five (focused entirely on issues), journalists rated their coverage at 3.4 on average saying, in effect, that issue-oriented stories outnumbered horserace ones. In fact, we found that almost 50 percent of all stories were essentially horserace coverage or dwelled in nonsubstantive information, while less than 20 percent dealt with substantive matters.

With issues, too, more than 80 percent of the journalists rated the economy as one of the three most important issues to cover. In fact, it was the leading one journalists cited. Yet stories about the economy amounted to less than 10 percent of all of the issue-focused campaign coverage we found. Terrorism, on the other hand, was named as one of the most important issues by only 48 percent of the journalists, but made up 17 percent of issue-focused stories.

Comparing Local with National Coverage

We also discovered that local journalists and newspapers covered congressional races in significantly different ways than national journalists did the presidential race. Though we had less congressional coverage to compare—since during our two-week examination we found an average of 50.6 stories per newspaper about the presidential race and only 6.3 stories about a specific race for Congress—local political reporting tended to be more substantive. The papers we analyzed for the presidential race had a significantly higher proportion (about 50 percent) of horserace stories than did those we examined for congressional races (about 25 percent). Likewise, coverage of the congressional races included a higher proportion of substantive stories—about policy issues and candidate competence—than did the presidential coverage. Stories about congressional races tended to also include more quotes from candidates than did stories about the presidential race. Articles dealing with congressional races were more descriptive, emphasizing what happened during the course of the campaign day, than those from presidential reporters, which concentrated more on analysis or interpreting the meaning of events.

In their survey responses, those who covered congressional races reported different news values than those tracking the presidential race. Both rated candidate debates, interviews with candidates, and interviews with pundits as having the highest news values. However, presidential reporters rated campaign TV commercials as having substantially higher news value than did congressional reporters. And congressional reporters rated campaign press releases more highly on this scale than did presidential reporters.

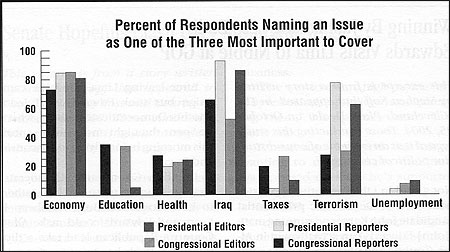

We also asked the journalists which three issues they considered more important to cover. While both congressional and presidential reporters rated the economy as important in approximately equal proportion, on Iraq they differed substantially, with 92.3 percent of presidential reporters and 65.4 percent of congressional reporters rating it an important issue in the context of their reporting. With terrorism, 76.9 percent of presidential journalists rated it important, while just 26.9 percent of congressional journalists did.

These foreign policy differences are not surprising since terrorism and Iraq were primary issues in the presidential campaign. Education and—perhaps more surprisingly—tax policy and the environment, were named as important by a higher proportion of congressional than presidential reporters.

The Intersection of Coverage

We also tried to learn whether congressional journalists felt national political reporting affected their coverage. What most influenced them was the topical focus of the national coverage (the emphasis on horserace vs. issues), as well as decisions on what issues to cover or ignore and stylistic aspects of the coverage. National reporters and editors (especially the latter) also indicated that they were influenced by the coverage of other national media, a finding we attribute to the near-instant access journalists had via Web sites and Weblogs to stories appearing throughout the country.

One clear message we received was that national journalists consider themselves a cut above their local counterparts in two respects: They believe their adherence to journalistic standards is higher, as is their expertise in coverage of national issues. This emerged as we asked all of the respondents in our survey whether national news organizations that “regularly cover presidential elections produce reports that are consistently superior to those of local or regional papers that provide occasional coverage of national politics.” We went on to ask those who agreed with this statement about the basis of their perceived superiority.

Interpreting the Findings

What can we learn from these results, as we look at these many responses that provide a tantalizing hint of the significantly opposing ways in which national and local journalists regard their work? One can assert that local papers provide a different kind of election coverage to their readers than do the national press. This is evidenced especially in the topics that are covered—with proportionally more substantive and fewer nonsubstantive stories found in coverage of congressional races. Local readers received coverage that was often more solidly grounded in reporting, offering descriptions of what happened and letting readers hear directly from the candidates. Unlike their national counterparts, local political reporters seem not to function as a Greek chorus providing context and meaning to the action on stage. Hence readers had more opportunities to draw their own conclusions as to the significance of campaign developments.

What we did not expect to find when we set out on this project was what we began to think of as a culture of confusion in the production of America’s political coverage. As we described earlier, there were significant differences between what the journalists thought (or said) they produced and what was actually published. Strikingly, reporters and editors significantly overestimated the substantive content of their stories.

When we tried to determine who is in charge of making decisions about what stories to cover, we learned that on this point, too, there appears to be some confusion, which likely accounts, in part, for the discrepancy between what journalists assert is important and what news actually reaches readers. The editors we surveyed were evenly divided as to whether they or reporters had the most control over stories. But when asked about decision-making of what to cover and how, nearly 80 percent of both local and national reporters said they made the call.

Anyone who has worked in a news organization knows that plans and good intentions can easily go astray. Yet we are troubled by the wide gulf that exists between what journalists told us they covered (or should cover) and what they put in front of readers. Reporters in the field need to make coverage decisions, but the discrepancy between reporters’ and editors’ perceptions of their control points to the need for a more coherent decision-making process. This apparent absence of one cannot possibly benefit readers.

On assessments of the importance of various sources of news, reporters and editors were again often on different pages. For example, editors regarded a local appearance by a candidate as a more important source of news than did reporters.

Interestingly, professional values clashed sometimes with the ability to do good journalism. In response to an open-ended question about why actual coverage diverged from their stated news values, editors reported that efforts to serve readers by providing balance and strict fairness resulted in some campaigns getting too much publicity while others got too little. Editors also affirmed the watchdog function of their news organizations, which often took the form of fact-checking commercials or scrutinizing candidates’ statements. In some cases, these values got in the way of substantive coverage. One editor told us that important issue and policy stories were overshadowed by those examining political commercials. Another said the newsroom was so busy doing ad watches that it could not find time to deal with issue-related stories.

Why This Matters

Are national and local campaign coverage becoming homogenized? If not, what do the differences that surfaced in our project mean for voters?

Inevitably, overlaps in local and national political coverage exist, as they always have. It would be ludicrous to assert that there should be one set of rules or values for local political journalists and another for reporters who cover presidential campaigns. Such dual-track journalism would not help readers. But we think that the following differences between presidential and local coverage that we uncovered in our content analysis are important:

These disparities were reflected in differing patterns of sourcing in presidential vs. congressional coverage.

The results of our study point to a paradox. National campaign coverage is abundant, but predominantly nonsubstantive. More than half of the stories by the national political press focused on the horserace. Local campaign coverage is scarce, but more substantive, with only 25 percent devoted to the horserace.

So the question is: How can national papers be encouraged to apply their impressive resources to the delivery of more substantive coverage? And how can local newspapers stretch their staffs and budgets to do more of what they already are doing well? And for all political journalists, the challenge remains to bring clarity, coherence and consistency to a process—vital for democracy—that seems too often mired in confusion.

By the middle of January, the 2004 campaign horserace was in full swing. In just a few days, the Iowa caucuses would select the nation’s first presidential delegates. In less than two weeks, New Hampshire would hold the first presidential primary. On February 3rd, seven more states would hold their primaries. Never had so many votes been cast so early, and never had they been so important in selecting a party’s presidential candidate.

While poll results are the most obvious manifestations of horserace coverage, the term also can include stories about the candidates’ strategies and fundraising, predictions of who will and will not turn out to vote, and other “nonsubstantive” topics that do not bring to citizens the information they need to make informed voting decisions. On the other hand, stories linking vital policy issues to candidates’ positions, competence and experience, as well as articles taking readers beyond the daily polling or the insider’s analysis of the campaign, provide the kind of substance voters need.

Horserace journalism has long been criticized—by those who practice it and by academic observers and even news consumers—but there is no denying its appeal on a number of levels. Such reporting produces fresh stories whenever a new poll is released, and it is cheap and easy to do. The “scientific method” of political polling also makes such coverage relatively immune to criticisms of bias. Moreover, by conducting polls, news companies offer powerful incentives for this horserace approach. During the 2004 political campaigns, CNN collaborated with Time to conduct polls; NBC News linked up with The Wall Street Journal; The New York Times with CBS News, and The Washington Post with ABC News. Journalists might grumble about the fixation on polls, but results from them are showcased by the nation’s most prestigious news outlets.

As the caucus and primary voting began, the polls were in alignment. The Democratic frontrunner was former Vermont Governor Howard Dean. CNN-Time and CBS-The New York Times placed Senator John Kerry, who would emerge as the candidate, fourth.

Examining the Coverage

We decided to take a close look at the techniques of election reporting as they would play out during the rest of the campaign. We brought to this task our varied perspectives of a political scientist, newspaper editor, and campaign researcher. We believed that in comparing techniques, assumptions and approaches of presidential campaign journalists with those of local reporters assigned to congressional races we might unearth some important differences. Among the questions we wanted to consider were the following:

- Was the horserace as compelling a news story in congressional campaign coverage as it seemed to be in a presidential race?

- Were the conventions of presidential reporting migrating down to the local level and affecting that coverage? And if so, how?

- Was the trend toward more analytical and interpretive political coverage taking hold in coverage of more local races?

- In short, was there a growing homogenization of U.S. election news? If so, what were some implications for voters?

RELATED ARTICLE

"Winning By Just Losing Less Badly; Edwards Visits Lima to Nibble at GOP"

- Stephen Koff In all, 101 reporters and editors representing 37 papers from every region of the country shared their thoughts and practices with us in an online survey. (To recruit these participants, we contacted managing or executive editors and asked for permission to approach the reporters and section editors responsible for election coverage. We invited 161 journalists to participate in our survey, of whom 101 agreed—a response rate of 63 percent.) Correspondents from major national newspapers agreed to discuss their coverage of the presidential race; for congressional races we reached out to local and regional newspapers whose circulation areas included districts where races were considered competitive. (National reporters received a slightly different version of our questionnaire than did local reporters; editors from both national and local papers received an identical third version.)

To compare what journalists said to what they did, we examined—through LexisNexis searches and by subscription—a selection of national and regional newspapers on a daily basis for the two weeks leading up to Election Day, November 2, 2004. The smallest of the papers had a circulation of 12,704, the largest more than two million. Because many of the editors and reporters were too busy to complete a lengthy questionnaire while the campaigns were in progress, the survey went out on November 10th.

We have divided our findings into two categories.

- Answers to questions we posed.

- A wholly unexpected picture that emerged of the journalistic environment and processes that govern election coverage.

This second category of findings surfaced when we noticed that in many instances the coverage we read reflected neither the news values nor production processes that the journalists reported following. For example, on a scale of one (focused entirely on horserace coverage) to five (focused entirely on issues), journalists rated their coverage at 3.4 on average saying, in effect, that issue-oriented stories outnumbered horserace ones. In fact, we found that almost 50 percent of all stories were essentially horserace coverage or dwelled in nonsubstantive information, while less than 20 percent dealt with substantive matters.

With issues, too, more than 80 percent of the journalists rated the economy as one of the three most important issues to cover. In fact, it was the leading one journalists cited. Yet stories about the economy amounted to less than 10 percent of all of the issue-focused campaign coverage we found. Terrorism, on the other hand, was named as one of the most important issues by only 48 percent of the journalists, but made up 17 percent of issue-focused stories.

Comparing Local with National Coverage

We also discovered that local journalists and newspapers covered congressional races in significantly different ways than national journalists did the presidential race. Though we had less congressional coverage to compare—since during our two-week examination we found an average of 50.6 stories per newspaper about the presidential race and only 6.3 stories about a specific race for Congress—local political reporting tended to be more substantive. The papers we analyzed for the presidential race had a significantly higher proportion (about 50 percent) of horserace stories than did those we examined for congressional races (about 25 percent). Likewise, coverage of the congressional races included a higher proportion of substantive stories—about policy issues and candidate competence—than did the presidential coverage. Stories about congressional races tended to also include more quotes from candidates than did stories about the presidential race. Articles dealing with congressional races were more descriptive, emphasizing what happened during the course of the campaign day, than those from presidential reporters, which concentrated more on analysis or interpreting the meaning of events.

In their survey responses, those who covered congressional races reported different news values than those tracking the presidential race. Both rated candidate debates, interviews with candidates, and interviews with pundits as having the highest news values. However, presidential reporters rated campaign TV commercials as having substantially higher news value than did congressional reporters. And congressional reporters rated campaign press releases more highly on this scale than did presidential reporters.

We also asked the journalists which three issues they considered more important to cover. While both congressional and presidential reporters rated the economy as important in approximately equal proportion, on Iraq they differed substantially, with 92.3 percent of presidential reporters and 65.4 percent of congressional reporters rating it an important issue in the context of their reporting. With terrorism, 76.9 percent of presidential journalists rated it important, while just 26.9 percent of congressional journalists did.

These foreign policy differences are not surprising since terrorism and Iraq were primary issues in the presidential campaign. Education and—perhaps more surprisingly—tax policy and the environment, were named as important by a higher proportion of congressional than presidential reporters.

The Intersection of Coverage

We also tried to learn whether congressional journalists felt national political reporting affected their coverage. What most influenced them was the topical focus of the national coverage (the emphasis on horserace vs. issues), as well as decisions on what issues to cover or ignore and stylistic aspects of the coverage. National reporters and editors (especially the latter) also indicated that they were influenced by the coverage of other national media, a finding we attribute to the near-instant access journalists had via Web sites and Weblogs to stories appearing throughout the country.

One clear message we received was that national journalists consider themselves a cut above their local counterparts in two respects: They believe their adherence to journalistic standards is higher, as is their expertise in coverage of national issues. This emerged as we asked all of the respondents in our survey whether national news organizations that “regularly cover presidential elections produce reports that are consistently superior to those of local or regional papers that provide occasional coverage of national politics.” We went on to ask those who agreed with this statement about the basis of their perceived superiority.

- One hundred percent of the national reporters who responded to the question agreed with the statement, and 67 percent of those who agreed said national news organizations had a “better grasp of professional standards.”

- Nearly two-thirds of journalists who covered local congressional races also agreed with this statement, but only four percent of them said national reporters had a better grasp of standards. Instead, they ascribed the perceived superiority of the national news organizations to their access to better sources, more newsroom resources available, and a better understanding of the issues.

Interpreting the Findings

What can we learn from these results, as we look at these many responses that provide a tantalizing hint of the significantly opposing ways in which national and local journalists regard their work? One can assert that local papers provide a different kind of election coverage to their readers than do the national press. This is evidenced especially in the topics that are covered—with proportionally more substantive and fewer nonsubstantive stories found in coverage of congressional races. Local readers received coverage that was often more solidly grounded in reporting, offering descriptions of what happened and letting readers hear directly from the candidates. Unlike their national counterparts, local political reporters seem not to function as a Greek chorus providing context and meaning to the action on stage. Hence readers had more opportunities to draw their own conclusions as to the significance of campaign developments.

What we did not expect to find when we set out on this project was what we began to think of as a culture of confusion in the production of America’s political coverage. As we described earlier, there were significant differences between what the journalists thought (or said) they produced and what was actually published. Strikingly, reporters and editors significantly overestimated the substantive content of their stories.

When we tried to determine who is in charge of making decisions about what stories to cover, we learned that on this point, too, there appears to be some confusion, which likely accounts, in part, for the discrepancy between what journalists assert is important and what news actually reaches readers. The editors we surveyed were evenly divided as to whether they or reporters had the most control over stories. But when asked about decision-making of what to cover and how, nearly 80 percent of both local and national reporters said they made the call.

Anyone who has worked in a news organization knows that plans and good intentions can easily go astray. Yet we are troubled by the wide gulf that exists between what journalists told us they covered (or should cover) and what they put in front of readers. Reporters in the field need to make coverage decisions, but the discrepancy between reporters’ and editors’ perceptions of their control points to the need for a more coherent decision-making process. This apparent absence of one cannot possibly benefit readers.

On assessments of the importance of various sources of news, reporters and editors were again often on different pages. For example, editors regarded a local appearance by a candidate as a more important source of news than did reporters.

Interestingly, professional values clashed sometimes with the ability to do good journalism. In response to an open-ended question about why actual coverage diverged from their stated news values, editors reported that efforts to serve readers by providing balance and strict fairness resulted in some campaigns getting too much publicity while others got too little. Editors also affirmed the watchdog function of their news organizations, which often took the form of fact-checking commercials or scrutinizing candidates’ statements. In some cases, these values got in the way of substantive coverage. One editor told us that important issue and policy stories were overshadowed by those examining political commercials. Another said the newsroom was so busy doing ad watches that it could not find time to deal with issue-related stories.

Why This Matters

Are national and local campaign coverage becoming homogenized? If not, what do the differences that surfaced in our project mean for voters?

Inevitably, overlaps in local and national political coverage exist, as they always have. It would be ludicrous to assert that there should be one set of rules or values for local political journalists and another for reporters who cover presidential campaigns. Such dual-track journalism would not help readers. But we think that the following differences between presidential and local coverage that we uncovered in our content analysis are important:

- Local election coverage seems more focused on descriptive reporting and on letting the candidates speak in their own voices.

- National coverage is based to a significant degree on analysis and on what journalists and other “experts” had to say.

These disparities were reflected in differing patterns of sourcing in presidential vs. congressional coverage.

- More than 10 percent of the national coverage used pundits as sources; less than four percent of the local stories relied on them.

- Independent experts—mainly academic specialists—were used in 39 percent of presidential stories vs. only 15 percent of the congressional coverage.

- Almost twice the proportion of presidential stories as congres-sional stories used other reporters as sources.

The results of our study point to a paradox. National campaign coverage is abundant, but predominantly nonsubstantive. More than half of the stories by the national political press focused on the horserace. Local campaign coverage is scarce, but more substantive, with only 25 percent devoted to the horserace.

So the question is: How can national papers be encouraged to apply their impressive resources to the delivery of more substantive coverage? And how can local newspapers stretch their staffs and budgets to do more of what they already are doing well? And for all political journalists, the challenge remains to bring clarity, coherence and consistency to a process—vital for democracy—that seems too often mired in confusion.