New media are not new to those who’ve grown up with or use them every day. To 18-year-old’s at our journalism school at Louisiana State University, iPods, satellite-reception, Wi-Fi, laptops, cell phones, PDA’s, digital photography, and the Internet are technologies as familiar as the wheel and fire. But while ancient innovations took millennia to spread, today a new gadget or idea can catch on globally within a few years.

The ascent of the Web log, Weblog (or blog) is one example. Within five years, online journals of political and personal expression and debate rose from obscurity to become ubiquitous. In examining how the mainstream press has reacted to blogs, we discern lessons about the relationship between technology and journalism:

Certainly blogs seem to be everywhere—some estimates put the number of blogs in the tens of millions. According to several Pew studies, of the estimated 120 million U.S. adults who use the Internet, some seven percent have created a blog while more than 30 million look at them regularly. Many blogs are basement setups—scribbled by one, read by few. In contrast, some popular blogs, like Instapundit, Power Line and Daily Kos, receive more daily traffic than many major newspapers or TV news programs.

But blogs aren’t talked about just because of their numbers, rather for the news they make while critiquing journalism and tracking events, such as blogging about the rise and fall of presidential candidate Howard Dean, Dan Rather’s “memogate,” Trent Lott’s praise of Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrat campaign, and the South Asian tsunami. In each case—and others—bloggers pushed and prodded old media to change the ways they work. In response, some journalists and news organizations have created blogs and use them for newsgathering, self-reflection, opinion-testing, and interaction with readers, listeners and viewers.

Though blog-like sites existed during the 1990’s—most notably the Drudge Report—blogs were officially born in December 1997, when Jorn Barger, editor of Robot Wisdom.com, created the term “Weblog.” In the spring of 1999, Peter Merholz broke “Weblog” into the phrase “we blog” and put it on his homepage. As the term spread, in August 1999 software-maker Pyra Labs released the program Blogger, making blogs user-friendly and generally accessible.

Blogs were not an instant big story in the mainstream media. One of the first hits for “blog” in the press was in October 1999 when Great Britain’s New Statesman described it as “a Web page, something like a public commonplace book, which is added to each day …. If there is any log they resemble, it is the captain’s log on a voyage of discovery.” The first newspaper reference likely occurred in January 2000 when Canada’s Ottawa Citizen quoted pop star Sarah McLachlan from her Web site. One of the first broadcast stories about blogs was in May 2000 when National Public Radio’s “The Connection” interviewed several bloggers.

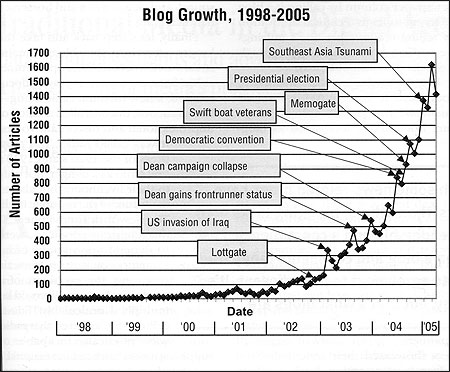

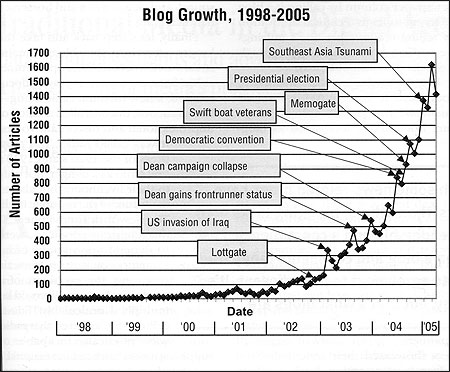

Overall, in tracking mainstream media’s reporting on blogs between January 1998 and April 2005, we found 16,350 items mentioning the words “Web log,” “Weblog,” and “blog.” [See chart on below.] In gauging “blog-throughs”—events commonly ascribed to have propelled blogs to media attention—we found that journalists were barely acknowledging blogs in the wake of 9/11.

Blog obscurity changed decisively in 2002, when Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, while attending a reception for South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, made a racially insensitive comment. The item was first mentioned by ABC News and posted on its Web site, but bloggers drumbeat the story into widespread salience. Lott ended up resigning his leadership position under party pressure. Still, as blogs gained stature as agenda-setters, they remained relatively lightly cited by the press.

In 2003, as the presidential primary season kicked off, Howard Dean’s team—led by technology-savvy Joe Trippi, Dean’s campaign manager—pioneered the campaign blog for the public and the press. Users posted messages to other supporters, and this networking ability enabled them to meet for events. Supporters were encouraged to “decentralize” by starting their Dean Web sites and to raise funds through their blogs. By September 2003 Dean’s blog was getting 30,000 unique visitors a day. When General Wesley Clark entered the race, he cited a “Draft Wes” Web site’s popularity and supportive blog comments as one reason to get in. The political parties and many candidates also began blogging. For example, the Democratic National Committee started up “Kicking Ass: Daily Dispatches from the DNC,” which promised “frank, one-on-one communication …. Blogs make that possible.”

Blogs were now being portrayed as voices of the people, political players, and as trip-wires for breaking stories.

Blogs Arrive

2004 was the year of the blog. That word became the most searched-for definition on several online dictionaries. Indeed in our tracking, October 2004 was the time at which 50 percent of blog coverage occurred before and after: In other words there has been as much blog news in the last half year as in the previous five. What follows are some of the more memorable news stories about blogs:

Pushing the Rather “memogate” story, bloggers simultaneously displayed their main virtue and vice—speedy deployment of unedited thought. One blogger on freerepublic.com posted his doubt about the memos’ authenticity: “They are not in the style that we used when I came in to the USAF. They looked like the style and format we started using about 12 years ago (1992). Our signature blocks were left justified, now they are rigth [sic] of center … like the ones they just showed.” Bloggers such as Power Line’s Scott Johnson launched an investigation of the purported memos. Innovatively, the blog little green footballs posted a file that contrasted a modern Microsoft Word recreation over CBS’s version of the disputed papers. The text was almost an exact match.

Within days, the story leapt from new media to the mainstream news media. For two weeks CBS News stood by its reporting, but then admitted that its document examiners could not verify the memos’ authenticity. The network launched an investigation to determine how the invalidated material ended up on the air. Eventually four people at CBS were blamed for the error. Rather, who anchored the evening news for 24 years, announced his retirement in November and left his position in March 2005. Many bloggers rejoiced at their power to topple venerable institutions. Freerepublic.com blogger “Rrrod” warned, “NOTE [sic] to old media scum …. We are just getting warmed up!”

More big blog news was ahead, including the following incidents:

In the tsunami coverage, in particular, old media took another step toward co-opting the new. Uncensored and unedited video surfaced in video blogs (vlogs) and people relied on the Internet to watch scenes from the disaster. Free of Federal Communications Commission regulations, vlogs showed grisly and gripping footage, while TV newscasts often censored their reports to avoid upsetting the American public. WaveofDestruction.org, created by an Australian blogger, posted 25 amateur videos of the event and in five days logged nearly 700,000 visitors. Soon American TV networks vied for broadcast rights. Norwegian editor Oliver Orskaug sold his video for $20,000 to CNN and ABC News.

Even as blogs soared in attention and influence, a blowback from the mainstream media was underway.

Graph created by David D. Permutter.

Blogs vs. Old Media

Given what’s happened with blogs and journalism, can we say that their upward trend is now in decline? Or are blogs being relegated to places where journalists troll for funny stories or human interest filler? Neither seems a likely outcome.

Blogs are likely to thrive due to their adaptability and innovation. Bloggers’ personal style, their technology, the use of open-end sourcing, and their ability to get information and speculation out quickly enable this new media to go around the clunky logistical trails and leadership—bypassing what economists call the “structural rigidity” of the old. Moments after the “60 Minutes II” story aired, for example, ABC News’s Peter Jennings was not going to break onto the air and proclaim, “There’s something screwy about a story on CBS.” And when a few bloggers had an idea about how to speed up and collate information about tsunami victims and survivors, they didn’t have to wait for an OK from senior editors or management. Blog failures cost much less than do those of mainstream media, so bloggers can experiment on a whim and do so faster than giant operations.

“Old world panic” is also a problem. At some level, blogs seem a threat to almost everything in the news business. OhmyNews, for example, is a South Korean Web site where anybody can post news stories and editorials; if the content proves popular enough, the author gets paid for it. If such a model becomes dominant, it would mean the end of journalism, not to mention journalism schools. But forcing new technology into old holes doesn’t work, either. Reading blogs on TV is artificial and unworkable, as is “hipping up” a newspaper column by calling it a blog or trying to feign technical innovation by telling readers that one’s musings were done on a Blackberry (though suspiciously without typos).

Regular media are challenged, too, about how to cover novelties in their business. Journalists noticed blogs late, but interest intensified as bloggers showcased their potential. Now a frenzy of attention by journalists is coupled with mocking. Is this an inevitable cycle—building up what is new to unwarranted levels of praise, then despairing at its flaws, which were evident at the start?

Blogs cannot be stuffed into ill-fitting stereotypes. Blogs represent the divergent voices of millions. Though some news-related blogs have more “hits” than others, blogging lacks both defined leadership and a constituency. Post an item on a blog and comments range from complete agreement to irate dissent. It’s messy, but that’s what blogs are, and we hope they stay that way.

Certainly traditional journalists have a right to feel as sports stars do when they have to endure catcalls and advice shouted at them by obnoxious fans. And compared with most journalists, a lot of the bloggers have not paid their dues in education, training or experience. But the problems that mainstream journalism is experiencing today have little to do with bloggers. After all, it wasn’t bloggers who slashed newsroom budgets for basic beat and investigative reporting. Nor did bloggers create a star system of astronomically paid anchors and pundits. And bloggers were not the ones who reduced coverage of political campaigns and elections to sound- and visual- bytes and horserace handicapping.

Finally, let’s step back and take the longer view into this blogger/mainstream media debate. Once upon a time, as historian Gwenyth L. Jackaway documented, a new medium came along—loud, raucous, uncontrolled and full of unprofessional and discordant voices. It was called radio. The print press of the 1920’s and 1930’s saw radio as a danger, not only to their livelihoods but also to the future of the republic itself. The New York Times fumed, “If the American people … were to depend upon scraps of information picked up from air reporting, the problems of a workable democracy would be multiplied incalculably.” Editor & Publisher asserted that radio was “physically incapable of supplying more than headline material,” and thus it was “inconceivable that a medium which is incapable of functioning in the public interest will be allowed to interfere with the established system of news reporting in a democracy.”

Print news survived and thrives and radio did not destroy democracy. There will always be a mainstream media, though perhaps blogs will blur into it. But the point worth remembering is that the rise of new media should not make the old media panic or be dismissive or fearful. Rather what is new ought to remind us of the need to grasp ever more tightly ahold of the fundamentals of journalism as we journey forward.

David D. Perlmutter is an associate professor at the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University and a senior fellow at the Reilly Center for Media & Public Affairs. He is writing a book on political blogs for Oxford University Press. Misti McDaniel is a master’s degree candidate at the Manship School of Mass Communication and has a background in political communication and research.

The ascent of the Web log, Weblog (or blog) is one example. Within five years, online journals of political and personal expression and debate rose from obscurity to become ubiquitous. In examining how the mainstream press has reacted to blogs, we discern lessons about the relationship between technology and journalism:

- Events don’t drive new media technology. Rather, new media technology succeeds by finding ways to exploit events.

- News coverage tends to focus on the sexy or “hot” aspects of new media technology, which can obscure other trends that will be potentially more influential in the long run.

- Old media portrays new media technologies as darlings, only to cynically then dethrone them.

- Traditional media’s vulnerabilities to such upstarts aren’t just technological but are economic and psychological. Mainstream media believe new things might destroy, result in unemployment, or make them obsolete; they don’t know how to adapt.

- The best response to blogs by television, radio and print is not to ape them but to determine what blogs do and why they do it well or poorly.

Certainly blogs seem to be everywhere—some estimates put the number of blogs in the tens of millions. According to several Pew studies, of the estimated 120 million U.S. adults who use the Internet, some seven percent have created a blog while more than 30 million look at them regularly. Many blogs are basement setups—scribbled by one, read by few. In contrast, some popular blogs, like Instapundit, Power Line and Daily Kos, receive more daily traffic than many major newspapers or TV news programs.

But blogs aren’t talked about just because of their numbers, rather for the news they make while critiquing journalism and tracking events, such as blogging about the rise and fall of presidential candidate Howard Dean, Dan Rather’s “memogate,” Trent Lott’s praise of Strom Thurmond’s Dixiecrat campaign, and the South Asian tsunami. In each case—and others—bloggers pushed and prodded old media to change the ways they work. In response, some journalists and news organizations have created blogs and use them for newsgathering, self-reflection, opinion-testing, and interaction with readers, listeners and viewers.

Though blog-like sites existed during the 1990’s—most notably the Drudge Report—blogs were officially born in December 1997, when Jorn Barger, editor of Robot Wisdom.com, created the term “Weblog.” In the spring of 1999, Peter Merholz broke “Weblog” into the phrase “we blog” and put it on his homepage. As the term spread, in August 1999 software-maker Pyra Labs released the program Blogger, making blogs user-friendly and generally accessible.

Blogs were not an instant big story in the mainstream media. One of the first hits for “blog” in the press was in October 1999 when Great Britain’s New Statesman described it as “a Web page, something like a public commonplace book, which is added to each day …. If there is any log they resemble, it is the captain’s log on a voyage of discovery.” The first newspaper reference likely occurred in January 2000 when Canada’s Ottawa Citizen quoted pop star Sarah McLachlan from her Web site. One of the first broadcast stories about blogs was in May 2000 when National Public Radio’s “The Connection” interviewed several bloggers.

Overall, in tracking mainstream media’s reporting on blogs between January 1998 and April 2005, we found 16,350 items mentioning the words “Web log,” “Weblog,” and “blog.” [See chart on below.] In gauging “blog-throughs”—events commonly ascribed to have propelled blogs to media attention—we found that journalists were barely acknowledging blogs in the wake of 9/11.

Blog obscurity changed decisively in 2002, when Senate Majority Leader Trent Lott, while attending a reception for South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, made a racially insensitive comment. The item was first mentioned by ABC News and posted on its Web site, but bloggers drumbeat the story into widespread salience. Lott ended up resigning his leadership position under party pressure. Still, as blogs gained stature as agenda-setters, they remained relatively lightly cited by the press.

In 2003, as the presidential primary season kicked off, Howard Dean’s team—led by technology-savvy Joe Trippi, Dean’s campaign manager—pioneered the campaign blog for the public and the press. Users posted messages to other supporters, and this networking ability enabled them to meet for events. Supporters were encouraged to “decentralize” by starting their Dean Web sites and to raise funds through their blogs. By September 2003 Dean’s blog was getting 30,000 unique visitors a day. When General Wesley Clark entered the race, he cited a “Draft Wes” Web site’s popularity and supportive blog comments as one reason to get in. The political parties and many candidates also began blogging. For example, the Democratic National Committee started up “Kicking Ass: Daily Dispatches from the DNC,” which promised “frank, one-on-one communication …. Blogs make that possible.”

Blogs were now being portrayed as voices of the people, political players, and as trip-wires for breaking stories.

Blogs Arrive

2004 was the year of the blog. That word became the most searched-for definition on several online dictionaries. Indeed in our tracking, October 2004 was the time at which 50 percent of blog coverage occurred before and after: In other words there has been as much blog news in the last half year as in the previous five. What follows are some of the more memorable news stories about blogs:

- As Howard Dean started his political slide out of the race, stories about blogs grew by 50 percent. Instead of seeking disgruntled supporters for face-to-face interviews, reporters cited Dean’s bloggers as newspapers carried articles about Dean’s blog and how its participants reacted to the campaign’s changing fortunes.

- In July 2004 the Democratic National Convention credentialed 35 bloggers. While 15,000 journalists were issued press passes, attention focused on the “bloggeratti.”

- Blogging exploded into view on September 8, 2004, when on CBS News’s “60 Minutes II” Dan Rather reported a story questioning President George W. Bush’s 1970’s National Guard service. Offered as evidence were papers, allegedly written by Bush’s then supervisor Lieutenant Colonel Jerry Killian, stating that Bush did not fulfill his service requirements.

Pushing the Rather “memogate” story, bloggers simultaneously displayed their main virtue and vice—speedy deployment of unedited thought. One blogger on freerepublic.com posted his doubt about the memos’ authenticity: “They are not in the style that we used when I came in to the USAF. They looked like the style and format we started using about 12 years ago (1992). Our signature blocks were left justified, now they are rigth [sic] of center … like the ones they just showed.” Bloggers such as Power Line’s Scott Johnson launched an investigation of the purported memos. Innovatively, the blog little green footballs posted a file that contrasted a modern Microsoft Word recreation over CBS’s version of the disputed papers. The text was almost an exact match.

Within days, the story leapt from new media to the mainstream news media. For two weeks CBS News stood by its reporting, but then admitted that its document examiners could not verify the memos’ authenticity. The network launched an investigation to determine how the invalidated material ended up on the air. Eventually four people at CBS were blamed for the error. Rather, who anchored the evening news for 24 years, announced his retirement in November and left his position in March 2005. Many bloggers rejoiced at their power to topple venerable institutions. Freerepublic.com blogger “Rrrod” warned, “NOTE [sic] to old media scum …. We are just getting warmed up!”

More big blog news was ahead, including the following incidents:

- When some bloggers heard of Sinclair Broadcasting Group’s plan to air an anti-[John] Kerry documentary, they organized letter-writing campaigns and boycotts and again pushed the item until it became a major story in the mainstream media.

- On Election Day, early exit polls indicated John Kerry held a lead over George Bush in a number of key states. Some bloggers pushed a “Kerry is winning big” headline. But the flexibility of the blogosphere was shown when bloggers Hugh Hewitt and Mark Blumenthal (Mystery Pollster) pointed out that exit polls were only scientifically valid in a state until after voting had finished.

- The December tsunami in Southeast Asia contributed to a 39 percent growth in newspaper coverage of blogs. Stories of victims surfaced in blogs, and for the first time traditional media were bypassed as a source as relatives searched for information about loved ones online.

In the tsunami coverage, in particular, old media took another step toward co-opting the new. Uncensored and unedited video surfaced in video blogs (vlogs) and people relied on the Internet to watch scenes from the disaster. Free of Federal Communications Commission regulations, vlogs showed grisly and gripping footage, while TV newscasts often censored their reports to avoid upsetting the American public. WaveofDestruction.org, created by an Australian blogger, posted 25 amateur videos of the event and in five days logged nearly 700,000 visitors. Soon American TV networks vied for broadcast rights. Norwegian editor Oliver Orskaug sold his video for $20,000 to CNN and ABC News.

Even as blogs soared in attention and influence, a blowback from the mainstream media was underway.

- Blame fell on bloggers for leaking the raw exit poll results on Election Day and spreading conspiracy theories afterwards.

- Some bloggers were outed for faking data or retroactively changing posts without notation.

- Some bloggers accepted pay from political candidates or parties but did not reveal the arrangement to their readers.

- Questions arose about whether blogs were, indeed, the “voice of the people” since most domestic and foreign blog creators are white journalists, professors, lawyers or middle-class professionals.

- CNN was ridiculed for creating an “Inside the Blogs” segment that consisted of people reading blogs on air—an exercise in synergy that drew laughs even from bloggers.

- In March 2005, “The Daily Show” skewered one of the intellectual fathers of blogging, New York University’s Jay Rosen, as the program’s correspondent satirized the entire idea of amateurs hosting a news and commentary Web site.

- Questions are raised about whether the number of blogs is inflated by ones that are inactive or are spam.

Graph created by David D. Permutter.

Blogs vs. Old Media

Given what’s happened with blogs and journalism, can we say that their upward trend is now in decline? Or are blogs being relegated to places where journalists troll for funny stories or human interest filler? Neither seems a likely outcome.

Blogs are likely to thrive due to their adaptability and innovation. Bloggers’ personal style, their technology, the use of open-end sourcing, and their ability to get information and speculation out quickly enable this new media to go around the clunky logistical trails and leadership—bypassing what economists call the “structural rigidity” of the old. Moments after the “60 Minutes II” story aired, for example, ABC News’s Peter Jennings was not going to break onto the air and proclaim, “There’s something screwy about a story on CBS.” And when a few bloggers had an idea about how to speed up and collate information about tsunami victims and survivors, they didn’t have to wait for an OK from senior editors or management. Blog failures cost much less than do those of mainstream media, so bloggers can experiment on a whim and do so faster than giant operations.

“Old world panic” is also a problem. At some level, blogs seem a threat to almost everything in the news business. OhmyNews, for example, is a South Korean Web site where anybody can post news stories and editorials; if the content proves popular enough, the author gets paid for it. If such a model becomes dominant, it would mean the end of journalism, not to mention journalism schools. But forcing new technology into old holes doesn’t work, either. Reading blogs on TV is artificial and unworkable, as is “hipping up” a newspaper column by calling it a blog or trying to feign technical innovation by telling readers that one’s musings were done on a Blackberry (though suspiciously without typos).

Regular media are challenged, too, about how to cover novelties in their business. Journalists noticed blogs late, but interest intensified as bloggers showcased their potential. Now a frenzy of attention by journalists is coupled with mocking. Is this an inevitable cycle—building up what is new to unwarranted levels of praise, then despairing at its flaws, which were evident at the start?

Blogs cannot be stuffed into ill-fitting stereotypes. Blogs represent the divergent voices of millions. Though some news-related blogs have more “hits” than others, blogging lacks both defined leadership and a constituency. Post an item on a blog and comments range from complete agreement to irate dissent. It’s messy, but that’s what blogs are, and we hope they stay that way.

Certainly traditional journalists have a right to feel as sports stars do when they have to endure catcalls and advice shouted at them by obnoxious fans. And compared with most journalists, a lot of the bloggers have not paid their dues in education, training or experience. But the problems that mainstream journalism is experiencing today have little to do with bloggers. After all, it wasn’t bloggers who slashed newsroom budgets for basic beat and investigative reporting. Nor did bloggers create a star system of astronomically paid anchors and pundits. And bloggers were not the ones who reduced coverage of political campaigns and elections to sound- and visual- bytes and horserace handicapping.

Finally, let’s step back and take the longer view into this blogger/mainstream media debate. Once upon a time, as historian Gwenyth L. Jackaway documented, a new medium came along—loud, raucous, uncontrolled and full of unprofessional and discordant voices. It was called radio. The print press of the 1920’s and 1930’s saw radio as a danger, not only to their livelihoods but also to the future of the republic itself. The New York Times fumed, “If the American people … were to depend upon scraps of information picked up from air reporting, the problems of a workable democracy would be multiplied incalculably.” Editor & Publisher asserted that radio was “physically incapable of supplying more than headline material,” and thus it was “inconceivable that a medium which is incapable of functioning in the public interest will be allowed to interfere with the established system of news reporting in a democracy.”

Print news survived and thrives and radio did not destroy democracy. There will always be a mainstream media, though perhaps blogs will blur into it. But the point worth remembering is that the rise of new media should not make the old media panic or be dismissive or fearful. Rather what is new ought to remind us of the need to grasp ever more tightly ahold of the fundamentals of journalism as we journey forward.

David D. Perlmutter is an associate professor at the Manship School of Mass Communication at Louisiana State University and a senior fellow at the Reilly Center for Media & Public Affairs. He is writing a book on political blogs for Oxford University Press. Misti McDaniel is a master’s degree candidate at the Manship School of Mass Communication and has a background in political communication and research.