An image of an American soldier wounded in the Iraq War is one of the few pieces of documentary evidence the American public can see to begin a process of separating propaganda—that war is quick and bloodless—from truth. As of May 2004, close to 10,000 American soldiers have been wounded in action and in combat support in Iraq. The number of injured Iraqis—insurgents and civilians—is believed to be about triple that number.

There are no lists of the wounded, unlike the dead. In The New York Times, the names of the dead are published almost every day. I look for their ages, their hometowns, caring less about their command units. I feel sorry for their families and friends, but then it’s finished. The dead tell no stories. The wounded survive and present us with our own complicity, since war is fundamentally evidence of our failure as individuals and as a state to be civilized and restrained.

Since October 2003, I have been making portraits and conducting interviews with Americans who were wounded in the Iraq War. I seek them out at their homes after they have been discharged from the military hospitals at Walter Reed in Washington, D.C. and Brooke Army in San Antonio, Texas. I stay away from the homecoming parades, the VFW initiation events, the yellow ribbons, the appearances with politicians. I want to see the soldier alone as each confronts his or her loss and considers the experience of war and life ahead.

Contradictions and Loss

These portraits are not sentimental; if anything, they are detached. They are done in a formal manner in that the person is aware of being photographed. The process takes a few hours and always begins with a taped interview in which I ask questions about life at home, the recruitment process, the injury, what he or she liked about the military, and the experience in Iraq. Lately, I’ve been asking them for their definitions of freedom and democracy, a question that often leaves them puzzled.

When viewed together, the words and photos create a complex, sometimes contradictory portrait. For example, one severely burned soldier whose face is a painful patchwork of scar tissue and skin grafts said without irony that he is “the perfect face of the Army.” He desperately wants to continue his military career, saying he became “addicted” to the Army. Another soldier, blind, without a leg, living alone in a camper, abandoned by his parents as a child, said that Iraq “was the best experience of my life.” One Marine said he joined because that’s what men should do. He sits on his bed, without a leg. Behind him, on the wall, is a giant airbrushed painting of a naked woman.

Despite the enormity of their physical injuries—most are in chronic pain and permanently disabled—when asked if they would go back, all of them reply “yes.” Television journalists reporting on the wounded, as well as some newspaper writers, tend to make a big deal out of this answer, as though it’s proof of the soldiers’ pro-war sentiment. I’ve learned that the question, asked in such a way, is completely meaningless and only perpetuates a simplistic understanding of service and loyalty. I ask the wounded two questions. “If you could go back, would you?” The answer is always “yes.” Then I ask, “If your platoon was home and your friends were out of Iraq, would you go back?” The answer is almost always “no,” or “I’m not sure.”

When I started this project, I wasn’t prepared for the physical damage I would see. I remember the first soldier I photographed was completely blind. His world is black from morning to night. Titanium plates hold his brain together. He has seizures and mood swings and sleeps often. I photographed him in his bedroom standing next to a giant deer that he had killed when he was 16 years old. Dangling from the antlers were the soldier’s dog tags and his army ranger berets. Below the deer was a picture of the soldier in uniform. This young man, tall and strong, first in his class of 228 rangers, trembled at the sound of the camera’s shutter.

They volunteered to serve in the military, but how much free choice went into their decision is debatable. “No option. There were no jobs,” said one. “I thought going to war was jumping out of planes. I didn’t know it could be bad,” said another who remembers having watched Desert Storm as a child and thought it was “interesting.” A rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) ripped through this soldier’s leg during a firefight in Fallujah on Halloween. He has had 15 surgeries, seven blood transfusions. He can barely walk and stands hunched over like an old man. His wife has to tie his shoes.

None of them expressed bitterness or self-pity. Some still seemed in a state of shock. Only one was openly angry and critical of what he called the Bush administration’s lies. This soldier, 20 years old, had his right arm blown off and his left leg mangled in a grenade attack. He agreed to be photographed because he said people need to know what’s happening. He was alarmed by the ignorance in his neighborhood in Santa Ana, California and described an encounter with a friend. “Dude, what happened to you?” his friend asked, seeing the hook where his right arm used to be. The soldier replied that he was wounded in Iraq, and the friend said, “I thought that war was over.”

Pro- and antiwar groups each want to use the soldier in their rallies, but he has declined all requests. Instead, he said, he is reading books about Iraq and asked me if I had seen the movie, “The Battle of Algiers.” He spoke to a group of high school drop outs, kids like he was before he joined the Army, and wants to do more public speaking or counseling. He is worried about his younger brother and sister, who both want to join the military. He blames television and movies for giving them a false impression of war.

Nina Berman is a photographer based in New York City. She has been documenting the political and social landscape in the United States for more than 10 years. Her pictures have been published in magazines throughout the world including Time, Newsweek, Fortune, Mother Jones, Harpers, Geo, and National Geographic. She teaches part-time at the International Center of Photography in New York. A book of the soldiers’ portraits and interviews, “Purple Hearts,” will be published by Trolley Books in August 2004.

.jpg)

Sgt. Jeremy Feldbusch, 24 years old, an Army Ranger from the 3rd Battalion, 75th Regiment, was injured April 3, 2003, defending the Hadithah Dam and awarded the Purple Heart and Bronze Star with valor. He is completely blind, his brain is held together with titanium plates, he suffers seizures and has some brain damage. Photographed in his home in Derry Township, Pennsylvania, October 18, 2003.

“I graduated from the University of Pittsburgh. I was a biology major. At one point in my life, I wanted to be a doctor. Even while I was going through college, I thought about going into the military. … I knew about the Middle East as much as I needed to. But it didn’t make a difference. I wasn’t fighting a political war with them anyway. That was already taken care of. That’s about it. I don’t have any regrets. I had some fun over there. I don’t want to talk about the military anymore.”

.jpg)

Pfc. Tristan Wyatt, 21 years old, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, lost his leg in a firefight in Fallujah on August 25, 2003. Wyatt has undergone 10 surgeries because of massive infections as a result of his wounds. Photographed at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., October 29, 2003.

“I was in the back of an armored personnel carrier. We got hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. It was a shitty day to say the least. I just kept shooting. I thought I was dead anyway. I’ve had to relearn everything from standing up to walking. I’d been snowboarding for close to eight years before I got hit, and I’m just hoping to be able to do it again. I want to go back to the military. I want my old job back. I was a combat engineer. We blew things up. I felt like my heart was in the right place over there.”

.jpg)

Marine Corporal Alex Presman, 26 years old, was injured outside of Baghdad, July 15, 2003, when a mine exploded in front of him. Photographed in his apartment in Sheepshead Bay, New York, October 28, 2003.

“I was born in Russia. We came in ’94. I think a man has to go through the military. … I just thought it was the right thing for me to do. We stopped for a break … four guys in front of me. I was following them, and boom, it took off my foot. It threw me up, and I just fell down. At first, I was a little shocked. I didn’t understand what happened. They medevaced me out, took me to Bethesda Naval Hospital, and they told me it had to be amputated. Nobody can prepare himself for that. But you know, it could have been worse.”

.jpg)

Sam Ross, 21 years old, an Army paratrooper and combat engineer with the 82nd Airborne Division, was gravely injured May 18, 2003, in Baghdad when a bomb blew up during a munitions disposal operation. Photographed at his home in Dunbar Township, Pennsylvania, October 19, 2003.

“I lost my left leg, just below the knee. Lost my eyesight …. I have shrapnel in pretty much every part of my body. Got my finger blown off …. I had a hole blown through my right leg …. It hurts a lot, that’s about it. You know, not really anything major. Just little things. I have a piece of shrapnel in my neck that came up through my vest and went into my throat and it’s sitting behind my trachea, and when I swallow, it kind of feels like I have a pill in my throat. It was the best experience of my life. … I’ve jumped out of airplanes, I got to play with mines, got to see how the Army works. I got to interact with people of another culture, people who live their lives 100 percent different than the way we live here. That’s something that one in a million people will never get to see in their lifetime—another culture.”

Pfc. Alan Jermaine Lewis, 23 years old, a machine-gunner with the Army’s 3rd Infantry Division, was wounded July 16, 2003, on Highway 8 in Baghdad, when the Humvee he was driving hit a land mine blowing off both legs, burning his face, and breaking his left arm in six places. Photographed at home in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, November 23, 2003.

“I remember every detail about my legs. Every detail from the scars to the ingrown toenails to the birthmarks to the burn marks. … I’ve always thought about death—just growing up in Chicago and living out here in this world. I had a friend when I was six years old …. He was shot in the head—I think it was a stray bullet. My oldest sister was killed by a stray bullet when I was just a couple of months old, and my father was killed when I was seven. … I’m actually glad that I did the military the way I did—that I lived in the world for a couple of years—because I never would have known what it would be like to live on my own and be able to have parties at my house and own a car and do things like that.”

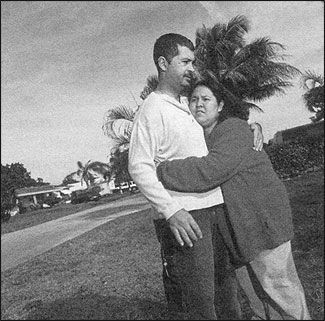

Platoon Sergeant John Quincy Adams, 37 years old, a National Guard reservist with Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 124th Infantry, was in a Humvee on August 29, 2003, when a remote controlled bomb exploded under his vehicle sending shrapnel into his brain and body. He has metal in the right lower quadrant of his brain, rock and shrapnel in his face, entry and exit wounds in his arm that damaged nerves and tendons in his hands and fingers, and is on medication for seizures, mood swings, and depressions that leaves him drowsy. He is not permitted physical activity since any fall could jiggle the metal in his brain, leaving him without speech or motor skills. Photographed at his home in Miramar, Florida with his wife, Summer, December 18, 2003.

“It was scary but I knew I had to do it. … It was pride. And to serve my country. It ran in my family. My father. My uncle. Everybody. … There is not that much I can do now. … My head doesn’t let me work, plus my arm. I was doing landscaping and lawn service in North Miami with my father-in-law. I loved it. … Now I like being with the kids and my wife. I try to be with them always.”

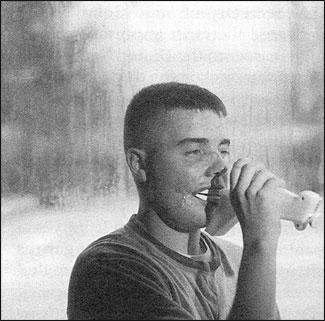

Pfc. Randall Clunen, 19 years old, an infantryman with the 101st Airborne, was on guard duty the night of December 8, 2003, when a suicide bomber broke through the perimeter and blew himself up along with his vehicle. Fifty-eight soldiers were wounded in the attack, including Clunen. The blast sent chunks of shrapnel into his face causing heavy bleeding and massive structural damage to his jaw and cheek. An emergency tracheotomy was performed so that he could breathe. He has had three surgeries and has several more to go. Photographed in his home in Salem, Ohio, February 14, 2004.

“I liked it. The excitement. The adrenaline. Never knowing what’s going to happen. I mean you could walk in the house, and it would blow up. Or you could go in and get fired at. I’m an adrenaline junky …. Start changing my life so I’m not as much an adrenaline junky. All the excitement that was going on, now it’s nothing. … My dad, we’d sit there and watch [television]. A lot of John Wayne movies too, you know, the cowboys and Indians, and then the war movies.”

.jpg)

Sergeant Wasim Khan, 24 years old, of the 2nd battalion First Armored Division, was manning a guard post on June 1, 2003, when an RPG ripped through the guard post shattering Khan’s leg and slicing his body with shrapnel. He has had 17 surgeries. Once an avid cricket player, Khan is now in constant pain and has limited use of his leg. An immigrant from Pakistan, Khan received his citizenship while recovering at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Photographed in his home in the Richmond Hill section of Queens, January 10, 2004.

“ I have shrapnel in my arms and my legs. I can feel them, they’re moving. In the shower, little pieces are falling out. I’m not really down to be honest with you. What happened, happened. … The good news is that I’m still alive, and God bless I still have both legs. I feel like I am part of history. In Washington we go out together, the Korean veterans, the Vietnam veterans, and now the Iraqi veterans. … Actually when I was here [in New York City] a couple of weeks ago they killed two Pakistani Muslims here in Brooklyn. … They called them Taliban, Taliban, and they shot them. But I’ve never had any problems.”

Photographs by Nina Berman/Redux.