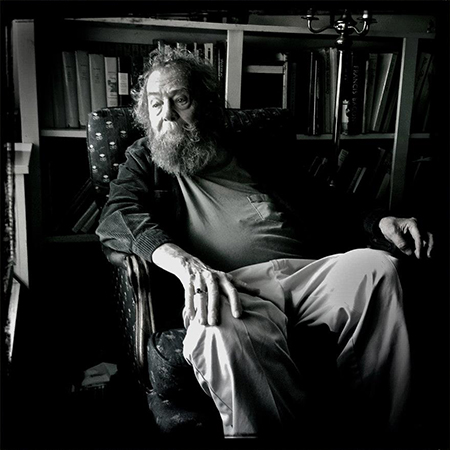

Donald Hall. Photo by Finbarr O’Reilly

Donald Hall, former U.S. poet laureate, has lived at Eagle Pond Farm, with its white clapboard farmhouse and weathered barn, in Wilmot, New Hampshire, since 1975. Hall grew up in the Connecticut suburbs but spent his summers at the farm haying, milking and doing other chores with his grandfather. I got to know Don in 1978 after moving to New Hampshire, when I read “String Too Short To Be Saved,” his memoir of his summers here. The rural life has long been his muse. I started inviting Don to visit the paper I edited, the Concord (N.H.) Monitor, to talk to staff about poetry and place and journalism. Don has written poetry, essays, criticism, plays, short stories, a novel. You name it, he’s done it, including journalism. He’s written for Sports Illustrated, the Ford Times, Yankee Magazine, and many, many others. I now come up here about once a month, and Don and I go over to a place we call Blackwater Bill’s to eat hot dogs. Don likes his hot dogs with the spicy mustard, and relish, and onions. We sat down at Eagle Pond to talk about Don’s work and the writer’s craft. Edited excerpts follow. —Mike Pride, NF ’85

An extended transcript and video of this interview is available.

MIKE PRIDE: Do you still read the paper regularly?

DONALD HALL: Yeah, I read two newspapers almost all my life. The New Haven Register and the New Haven General Courier. The Courier was the morning paper, the small, poor one. The Register was the big one. I moved to Ann Arbor, where I was a teacher at the University of Michigan [and] read The Ann Arbor News, which was not very good. I added The Detroit Free Press to it, so I read two papers a day. Then I came up here, and it is the Concord Monitor, which is the local paper, and The Boston Globe. I should say I read The Economist also. The Economist is a Time magazine that happens to be good. There’s a part of me that doesn’t seem like the rest of me that wants to know what’s happening everywhere. The Economist fills me in on the rest of the universe. I get the simple local news from my newspapers.

You don’t use the Internet at all?

I don’t have a computer. I’m probably the last person on Route 4 not to have a computer. I had a fax machine, and everybody I was faxing turned out to be keeping their fax machine only because of me. That was the quickest I had. Everything has to be quick now. I still write a lot of letters and get away with it. I worry about the general speeding up of words in the world. I worry about the intelligent young people, students, for whom reading is too slow. All they want is a bit of information. They can get that very easily from Google. Certainly they can get entertainment through games, television, television on the Internet, everything. Everything can be quick and sudden, delayed, or finished quickly.

When I was an editor, I would tell my staff to try to write for the newspaper as though they were writing a letter to an intelligent friend. I’m not even sure that if I said that today to a newspaper staff, they would be able to understand the analogy or the comparison.

A letter? What’s that?

Mike Pride, left, with Donald Hall at Eagle Pond Farm in New Hampshire. Photo by John Soares

For many years, you and I drove together down to Lippmann House and spoke with the Nieman Fellows about what a poet could teach journalists about writing. Why don’t we start with one of our favorite subjects, the dead metaphor?

Absolutely. All winter I read in The Boston Globe and probably in the Monitor about a “blanket of snow.” Isn’t that wonderful? It always annoys me, of course. There are words that are used in the headlines because they are short. But dead metaphors are something I notice all the time. You can kid yourself so easily. I have written a draft of a poem 50 times, 60 times, and see a gross dead metaphor in it. It’s easy enough to do it.

I remember telling a girl over at Cornell one time that I never say “dart” for a person moving quickly because “dart” is English invented in pubs. A dart is an arrow and using that as a verb … it’s like, “I was anchored to the spot” or “I was glued to the spot” means that a ship in a harbor and Elmer’s glue are the same thing. Remember that, and maybe it will help you avoid a dead metaphor.

From a practical standpoint, what you’re really talking about is helping writers pick the more precise word, right?

It is precise, because it’s not something under the surface, another object. It’s looking straight forward. There are people who say that everything in language is originally a metaphor, and I don’t understand the thought, but I don’t deny it. With prose that is full of dead metaphors, no character can get through. Everything has a veil between the utterance of the speaker and the perception of the reader, the listener. Somehow plainness is more intimate than the word “shrouded,” the word “blanketed.” A shroud is a shroud, and that’s fine. A blanket is a blanket. I can write about it, but don’t confuse it with an item that covers.

In your poems often sound is a driving force. To what extent do you think that is applicable to prose in newswriting?

I think sound has been for me the doorway into poetry, and by sound I particularly mean the repetition of long vowels more than anything else. It’s always repetition, and repetition sometimes has a slight difference. I always say that I read not with my eyes and I hear not with my ears with poetry. I hear and see through my mouth, the mouth itself. Then a reaction to the sounds, it’s kind of dreamy and intimate. It opens up (dead metaphor) the alleyway to the insides. This I particularly apply to poetry, and I think it is the chief difference. In poetry, we have the line break to organize the rhythm and sometimes to give emphasis.

Mix up long and short sentences. Mix up complex and compound and simple sentences. That’s easy. It is a matter of rhythm of the dance. There is something bodily about the rhythm of a paragraph, and there is a rhythm within a paragraph. Someone like John McPhee can write four pages without needing a paragraph because he is so terrific on transitions. But he is quite apt to have a four-page paragraph and then a one-line paragraph. That could be wonderful. Newspapers can do that, too, but most newspapermen do not have time to write 42 drafts of every piece.

The structure of a news story is a kind of form itself: the new news and the background afterwards and so on. An editorial writer is sort of freer to be wild and metaphoric than a news writer. The news writer, you know, the Jack Webb thing, “Nothing but the facts, ma’am.” It has to feel like that, but there can still be adjustment in rhythm and the type of sentence to engage the aspects of the reader which do not have to do only with fact but with some bodily joy and pleasure.

You recently stopped writing poetry. How did that happen?

It happened gradually and I didn’t know it was happening. Poems used to come in little meteor showers. I would begin three or four poems in two or three days. They’d come to me. I’d be sitting or I’d be driving and I’d pull over to the side of the road and write something down. Then it might not happen for six months, but I had four or five new poems to work on. Rarely, but occasionally, they would turn out to be the same poem. But they felt different, so that stopped, the meteor showers stopped coming.

I knew a lot about poetry and I had been working in it for years. I pushed; I didn’t know how to stop. But in 2008, I began the last two poems I wrote and I worked on them a couple of years. But I knew, by that point, pretty certainly that this was the end of it. It had gone slowly. I had done it for 60 years. What am I complaining about?

I began to substitute prose for poetry. When I published a piece in The New Yorker called “Out the Window,” I talked about getting old and I talked about not writing poetry anymore. Many people wrote me and said, “It is poetry.” If you call something poetry to praise it, that’s fine, but it’s not a poem. It’s something else again. It works by the paragraph, within the paragraph by types of sentences. But certainly by rhythm; God, rhythm is utterly important to prose.

I read whole books of prose that are intelligent and full of fact and so on and never does the author ever seem interested in writing anything that’s beautiful or that’s balanced or rhythmic. It’s hard for me to finish those books, intelligent and informing as they may be.

But without beautiful writing.

I love the writing, but I love the rewriting, too. In fact, rewriting is much more fun than writing and that was always true with poems or everything, because the first draft always has so much wrong with it. That’s one reason I admire a good newspaper. I cannot imagine being able to do it steadily, completely and finished. If I had been [a newspaper journalist], I probably could have learned how to do it, but it’s very distant now from the way I’ve worked.

What are your writing habits now?

I change individual words, get more precise. One thing that’s kind of common is that any verb-adverb combination can be done better with a more exact verb. I take out adjectives. So many times, I qualify. I say, “Sometimes I don’t remember when,” and all you have to say is, “Once something happened” or something. You’re always cutting, very seldom adding. But sometimes you realize that you left out something important, and you put it in.

Talk a little bit about “Out the Window,” published last year in The New Yorker.

One of my dogmas, a lot of people’s dogma, is that everything has to have a counter-motion within it. I wrote about looking out the window, sitting passively watching the snow against the barn, loving the barn and watching it. Then I went into the other seasons I could see out the window. It was all sort of one tone, a kind of old man’s love of where he lived and what in his diminished way he could enjoy without any sense of loss. I was almost finished with it at one point, and then this wonderful thing happened.

I went to Washington with Linda [his longtime companion], and we went to the various museums. In the National Gallery, there was a Henry Moore carving. I had written a book about Henry Moore. A guide came out and said, “That’s Henry Moore, and there’s more of them here and there.” Thank you.

An hour or two later, we had lunch; this is the National Gallery. When we came out from lunch, the same guy was there. My legs have no balance, and Linda was pushing me in a wheelchair. The same guy asked Linda, “Did you like your lunch?” And Linda said, yes. Then he bent down to me in the wheelchair, stuck his finger out, waggled it, and then he got a hideous grin and said, “Did we have a good din-din?”

And people said, “Did you pop him?” No! We were just sort of amazed and walked away without saying anything more. But then, I thought it was very funny. Because I was in a wheelchair I obviously had Alzheimer’s, and it made me think of little pieces of condescension. I thought about this, but especially the story about the guard gave me the counter-motion: “So, you like being old!” or whatever people who condescend to you do.

I got tons of mail about that essay, and people said it’s really poetry. But a lot of them talked about the museum guard, and they were sort of indignant, “Why didn’t you pop him?” and so on.

You have said that you are revising your essays a great deal more now. What are you looking for in a revision?

I know that when I wrote “String Too Short To Be Saved,” it was soft and luxuriant to remember, and I had room for some images that I remember with pleasure, like “seeing a whole forest of rock maple trees knocked down by one blast of the hurricane, like combed hair.” I like that. But many years later, when I wrote “Seasons at Eagle Pond,” a book of essays about life at the farm, my prose had become much more conscious of itself, and sort of showy. I think it takes so much longer, probably, not because of its nature, but because my energy is less, and maybe my imagination needs to go over a set of words many times to get it right. But I don’t mind. I like it a lot, and I dream up new things. Some of them are funny. At the beginning, my poems had nothing to do with me, almost all of them. As my life has gone on, one thing I’ve said is I began writing fully clothed and I took off my clothes bit by bit. Now I’m writing naked.

Mike Pride, a 1985 Nieman Fellow, is a historian, freelance writer, and editor emeritus of the Concord (N.H.) Monitor, where he ran the newsroom for 30 years. His latest book is “Our War: Days and Events in the Fight for the Union.”