Newspaper reading isn’t a daily habit for most young people. Instead they catch headlines on Web sites, share opinions on Weblogs, and see breaking news alerts along TV scroll bars. Nor do they think they should pay for news reporting. “Deliver the newspaper to me free, and I’ll take a look,” typical young readers tell focus groups as news organizations look for ways to unlock the mysteries of how to connect with these reluctant consumers.

At the Reading (Penn.) Eagle, Lisa Scheid, editor of Voices—the newspaper’s weekly outreach to teen readers—explains that Voices “has built its reputation on showing teens as they really are, not how someone wants them to be or thinks they should be.” Teens write for Voices about their lives and what interests them and, as Scheid says, Voices “needs to reflect their life, or they won’t read it.”

From Brazil, former magazine editor Thomaz Souto Corrêa reminds us of the international nature of this big gap that separates older generations from younger ones. “We are ‘monomedia’ when they are ‘multimedia,’” Corrêa writes. “These kids want us to be multimedia, too, and to reach them we will need to stop thinking in ways that are ‘monomedia.’” With his CD “Media Wars,” Mediachannel.org founder Danny Schechter combines media criticism with music. This, he says, flows “out of the theory that believes that if the news business is to reach this audience, it will have to speak its language and echo its concerns.”

John K. Hartman, a professor of journalism at Central Michigan University, has examined much of the research done on young adult newspaper readership. Among the myths he takes on is that “publishers used to cling to the notion that people acquired the newspaper habit as they got older: Just wait, they’d say, for the kids to grow up.” Tom Curley, president and CEO of The Associated Press who worked for several decades at USA Today, turns to French editor Francois Dufour for guidance about how to attract younger readers. Make it quick, newsy and useful, is among the advice he passes on. Then Curley adds some of his own: “Make it free, or nearly so.”

Steve Coll, managing editor of The Washington Post, talked with Nieman Reports about how and why his newspaper recently launched two publications—Express, a free daily newspaper created for commuters, and Sunday Source, a section designed with the sensibilities of younger readers—and about how the Internet fits into the paper’s strategy. Henry B. Haitz III, president and publisher of the Centre Daily Times in State College, Pennsylvania, writes about connecting with Penn State students by hiring a young staff to publish Blue, a weekly youth-oriented wraparound section, and figuring out how to market this new product. When its consumers were asked, says Haitz, “[they] let us know that they didn’t like being stereotyped as only caring about sex, drugs and rock’n roll.”

Colleen Pohlig edits Next, a youth publication at The Seattle Times. As she puts it, “To compete with the Internet and have a chance at attracting young people, newspapers must offer a combination of goods: authentic and edgy news coverage, more international news, stories with more young voices, fresh writing and designs, interactive options such as blogs and forums and, perhaps most importantly, flexibility.” Joe Knowles coedits RedEye, the Chicago Tribune’s weekday newspaper for young commuters. “The biggest challenge remains getting people to simply make the effort to pick up a paper—any paper,” he writes. At the Tribune Company’s Orlando Sentinel, Managing Editor Elaine Kramer learned what younger people want from newspapers, then put some of those lessons to work. In time, she believes, newspapers “will have to figure out how to deliver a newspaper for free.”

Jennifer Carroll, who directs development at Gannett Company, Inc., highlights the extensive research her company has done and points to approaches some Gannett papers have taken to attract young readers. These newspapers are “revamping content and presentation, experimenting with new sections, launching free weeklies … improving online content, and expanding delivery.” At Gannett’s Arizona Republic, Deputy Managing Editor Nicole Carroll writes about her newspaper’s challenge to create a product that would “move the needle” with a young female audience that wasn’t reading the paper. Yes—Your Essential Style, became the paper’s weekly vehicle. And at The Record in New Jersey, staff writer Leslie Koren had just turned 30 when she took on a new challenge of writing stories with people her age and younger in mind. “I want to speak to that part of the young readers that is still developing and coming into its own. I want to help them make sense of their world and encourage them to think for themselves.”

Journalist Leah Kohlenberg engages elementary school students in journalism as she teaches them how to report and write stories. “It was evident that if these students were going to write for a newspaper, they had to learn to read one,” she writes. Editor & Publisher managing editor Shawn Moynihan’s work as a substitute teacher taught him how kids look up to journalists. “… kids are not going to come to the newspapers—so newspapers must go to the kids,” he writes. In Los Angeles, Donna C. Myrow, founder of L.A. Youth, a newspaper written by teens for teens, writes about the paper’s important partnership with the Los Angeles Times. And Ellin O’Leary, president and executive producer of Youth Radio, describes how young people working in their newsroom with experienced journalists produce shows geared toward young audiences.

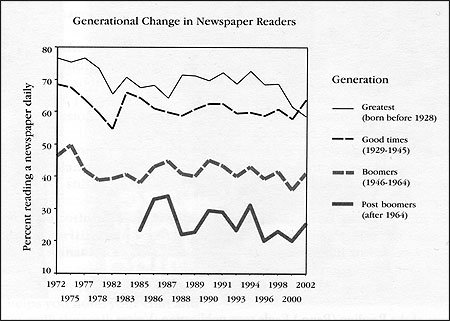

The belief that as young people grow older, they adopt the newspaper reading habits of their elders is a myth. As this chart shows, members of each generation tend to maintain their reading habits as they get older. Data: General Social Survey of the National Opinion Research Center, University of Chicago. Analysis: Phil Meyer, Knight Chair in Journalism, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.