I knew I had arrived as an important member of my family when I was allowed to lift the 50-pound bag of rice at the grocery store and take it into the house once we got home. It meant I had grown strong and tough enough to do what I had seen my oldest brothers and father do many times. It was a rite of passage, at least to me.

Rice was a staple in our diets — the staple in our diets — in the rural part of South Carolina where we lived, and our lineage can be traced to enslaved people on plantations where rice was cultivated. Dinner was not dinner without white rice. Sometimes dinner was white rice drenched in red ketchup. Sometimes dinner was scrambled eggs mixed in with white rice. Sometimes lunch was not lunch without rice. Sometimes a 50-pound bag would barely last a week in our family, which at its peak capacity included a mother and a father, 11 siblings by birth, and a handful of cousins raised like our brothers and sisters. We packed into a tin can of a home, a single-wide trailer with tin sides and a tin roof that we built onto. It was all we could afford. And if the price of rice went up by a few cents a pound at the local IGA or Red & White Foodland, it hit us. Hard.

It did not matter the cause of the price increase. Supply chain problems. An inflationary bubble caused by Federal Reserve policy. A strike by rice producers. Legislators removing subsidies from farmers somewhere in the Mississippi Delta. I’m sure that’s what we would have told a CNN camera crew had they been around then. I’m equally sure that’s the kind of story CNN was trying to tell when it decided to air a segment on inflation that focused on a blended family nearly as large as the one I grew up in. The idea was a solid one, but the story was so poorly executed it became a parody of itself.

White rice wasn’t the featured staple in that family’s diet. It was milk, an inordinately large amount, at least to those not in families as large as ours. Just as my family’s size and penchant to buy one thing in bulk would have stood out in our story, that family’s milk consumption did in theirs, particularly when its matriarch made this claim:

“A gallon of milk was $1.99. Now it's $2.79. When you buy 12 gallons a week times four weeks, that's a lot of money.”

The woman’s claim isn’t the problem; it’s how CNN framed what she said and what her family represented. Milk prices vary by the region and store, and that level of nuance can’t fully be captured in macroeconomic spreadsheets. That woman could have been accurately describing what she had been experiencing shopping in her area even if overall milk prices haven’t soared over the past year. But the story did not include an attempt to put any of that into context even as the woman and her family were being used as the personification of inflation’s real-world effects. That was a small oversight compared to others.

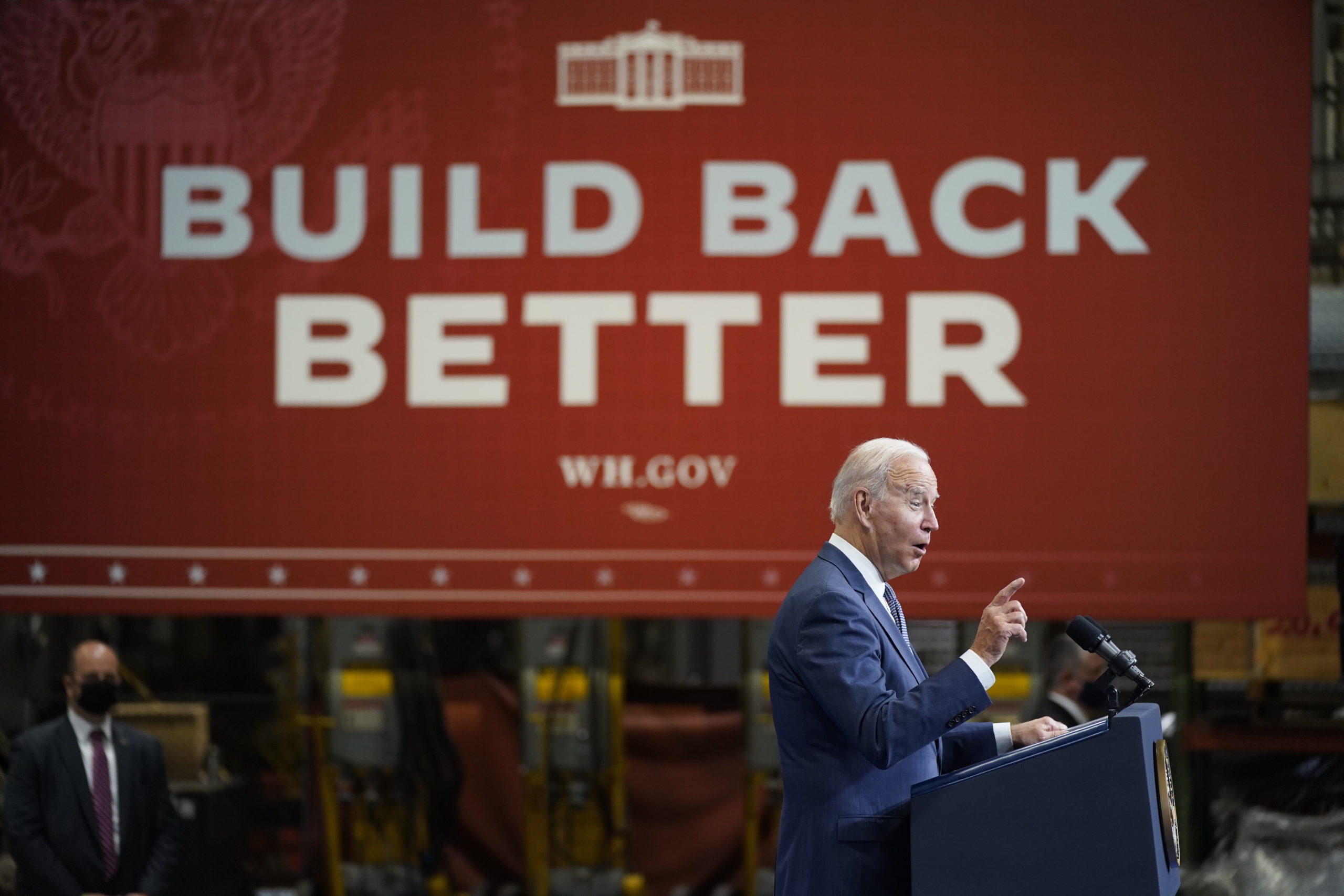

CNN has spent a considerable amount of time over the past few months tracking the innerworkings of what might become the Build Back Better law, which began as a $6 trillion dream by progressives whittled down to less than a third of that figure in negotiations with Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. But none of that important reporting was used in the story. Not only that, it gave no sense of broader economic realities, including how the incomes of blue-collar workers are rising, in some cases faster than inflation, meaning millions of Americans are in better financial positions because of the combination of the state of the market and government assistance.

CNN could have used this family’s situation to humanize what’s at stake in those high-stakes negotiations on Capitol Hill. Would any of that proposed spending help struggling families like the one featured in that story with health care? With child care? Would it give them peace of mind to know that the proposed law could extend the child tax credit beyond this year? How has that tax credit, made possible because of Democratic votes in Congress earlier this year, helped that family in 2021? If you watched CNN at all over the past few months, you know that the proposed bill has been dubbed “BBB” and for a long while had a $3.5 trillion price tag — a figure that includes a decade of spending, not a single year. But you still wouldn’t know what it would mean for that family.

After the story aired and criticism poured in, CNN’s Brianna Keilar tweeted this:

Days later, Daniel Lippman, Politico White House reporter, dug further and tweeted this:

Keilar explained even more context, including why manufacturers have cut back on coupons that families such as these could have relied upon — the kind of context that should have been included in the story rather than tweets after the fact and in response to criticism. That’s no small thing. How the media frames such stories, what context we include and what we don’t, matters greatly. It affects the shape of policies that are potentially transformative for families feeling the pinch of inflation in an age of high inequality.

The New York Times recently published a news analysis under this headline: “Americans are flush with cash and jobs. They also think the economy is awful.” It explains that disconnect by concluding it is the result of “the psychological effects of inflation.”

I suspect that has something to do with it, as does a hyper-partisanship that colors our perceptions of just about everything. It’s also a function of how the media explains what a 6.2 percent rise in consumer prices means in an economy that has produced an 11 percent income increase for restaurant workers, and frames aggressive governmental policies first designed to get us through the Covid-19 shock and now to shore up the safety net. Our economic reporting must accurately portray macro and micro realities and how they influence each other. Some families are experiencing a net loss of overall household income, while others have experienced a net gain. When we fail to explain that, no wonder our audiences are more likely to miss the forest for the trees.

Rice was a staple in our diets — the staple in our diets — in the rural part of South Carolina where we lived, and our lineage can be traced to enslaved people on plantations where rice was cultivated. Dinner was not dinner without white rice. Sometimes dinner was white rice drenched in red ketchup. Sometimes dinner was scrambled eggs mixed in with white rice. Sometimes lunch was not lunch without rice. Sometimes a 50-pound bag would barely last a week in our family, which at its peak capacity included a mother and a father, 11 siblings by birth, and a handful of cousins raised like our brothers and sisters. We packed into a tin can of a home, a single-wide trailer with tin sides and a tin roof that we built onto. It was all we could afford. And if the price of rice went up by a few cents a pound at the local IGA or Red & White Foodland, it hit us. Hard.

It did not matter the cause of the price increase. Supply chain problems. An inflationary bubble caused by Federal Reserve policy. A strike by rice producers. Legislators removing subsidies from farmers somewhere in the Mississippi Delta. I’m sure that’s what we would have told a CNN camera crew had they been around then. I’m equally sure that’s the kind of story CNN was trying to tell when it decided to air a segment on inflation that focused on a blended family nearly as large as the one I grew up in. The idea was a solid one, but the story was so poorly executed it became a parody of itself.

White rice wasn’t the featured staple in that family’s diet. It was milk, an inordinately large amount, at least to those not in families as large as ours. Just as my family’s size and penchant to buy one thing in bulk would have stood out in our story, that family’s milk consumption did in theirs, particularly when its matriarch made this claim:

“A gallon of milk was $1.99. Now it's $2.79. When you buy 12 gallons a week times four weeks, that's a lot of money.”

The woman’s claim isn’t the problem; it’s how CNN framed what she said and what her family represented. Milk prices vary by the region and store, and that level of nuance can’t fully be captured in macroeconomic spreadsheets. That woman could have been accurately describing what she had been experiencing shopping in her area even if overall milk prices haven’t soared over the past year. But the story did not include an attempt to put any of that into context even as the woman and her family were being used as the personification of inflation’s real-world effects. That was a small oversight compared to others.

CNN has spent a considerable amount of time over the past few months tracking the innerworkings of what might become the Build Back Better law, which began as a $6 trillion dream by progressives whittled down to less than a third of that figure in negotiations with Democratic Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema. But none of that important reporting was used in the story. Not only that, it gave no sense of broader economic realities, including how the incomes of blue-collar workers are rising, in some cases faster than inflation, meaning millions of Americans are in better financial positions because of the combination of the state of the market and government assistance.

CNN could have used this family’s situation to humanize what’s at stake in those high-stakes negotiations on Capitol Hill. Would any of that proposed spending help struggling families like the one featured in that story with health care? With child care? Would it give them peace of mind to know that the proposed law could extend the child tax credit beyond this year? How has that tax credit, made possible because of Democratic votes in Congress earlier this year, helped that family in 2021? If you watched CNN at all over the past few months, you know that the proposed bill has been dubbed “BBB” and for a long while had a $3.5 trillion price tag — a figure that includes a decade of spending, not a single year. But you still wouldn’t know what it would mean for that family.

After the story aired and criticism poured in, CNN’s Brianna Keilar tweeted this:

The child tax credit has been essential for them and they’re very thankful for it. It spared mom and dad from taking on second jobs and helped offset the rising cost of food, gas and utilities, but they’re still feeling the squeeze on their grocery bill.

Days later, Daniel Lippman, Politico White House reporter, dug further and tweeted this:

When I asked Krista Stotler from this CNN story if her family had received extended child tax credits over the past few months, she told me: ‘We only have three kids under the age of 18 and don’t really have a comment on that. …We’re just trying to raise our kiddos.’

Keilar explained even more context, including why manufacturers have cut back on coupons that families such as these could have relied upon — the kind of context that should have been included in the story rather than tweets after the fact and in response to criticism. That’s no small thing. How the media frames such stories, what context we include and what we don’t, matters greatly. It affects the shape of policies that are potentially transformative for families feeling the pinch of inflation in an age of high inequality.

The New York Times recently published a news analysis under this headline: “Americans are flush with cash and jobs. They also think the economy is awful.” It explains that disconnect by concluding it is the result of “the psychological effects of inflation.”

I suspect that has something to do with it, as does a hyper-partisanship that colors our perceptions of just about everything. It’s also a function of how the media explains what a 6.2 percent rise in consumer prices means in an economy that has produced an 11 percent income increase for restaurant workers, and frames aggressive governmental policies first designed to get us through the Covid-19 shock and now to shore up the safety net. Our economic reporting must accurately portray macro and micro realities and how they influence each other. Some families are experiencing a net loss of overall household income, while others have experienced a net gain. When we fail to explain that, no wonder our audiences are more likely to miss the forest for the trees.