In recent months the daily press has perched on the edge of repentance. With some justification it has been blamed by critics of all stripes for falsifying, trivializing, distracting the public with juicy gossip, chasing sensational stories in the company of the shameless tabloids, disregarding major social issues and discarding useful safeguards such as the verification of facts.

The demeaned and distrustful public compounds journalism’s dilemma by demanding better journalism while at the same time patronizing the worst. The public’s ambivalence is reflected in journalistic indecision. In other tabloid periods—the 1920’s, for example—editors argued that the public demands trash and as long as it does, not much can be done to improve the quality of journalism. While they may at times be tempted, editors of the late 1990’s who are trying to find ways to revive the affections of readers and viewers cannot afford to blame the public.

Blaming the vulgarians might have been possible in more confident times, but not in an age of prolific, crisscrossed competition when nobody can feel very confident about having a hold on any large part of the public. The tendency to blame the public has shown itself at times, usually in shruggingly apologetic what-can-we-do anyway disclaimers, but it’s not convincing. The precious credibility of journalism is at stake and journalists have to find more effective answers for the misdoings of all sectors of that blurred entity called “the media.”

The time seems right for a frank acknowledgment of errors committed by careless or greedy journalists, or crypto- or pseudo-journalists, and for a determined revival of the values that most journalists have been following in any case. “I can’t recall a better time for owning up to our mistakes,” said Reid MacCluggage, Editor and Publisher of The Day Publishing Company of New London, Conn., and President of the Associated Press Managing Editors. Like many editors, MacCluggage is feeling very frustrated by the fact that at the same time the reputation of journalism has been suffering, newspapers themselves “are better than they ever have been,” and many if not most are making some efforts to get the public involved with their local papers.

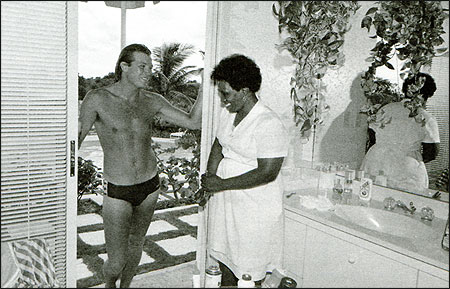

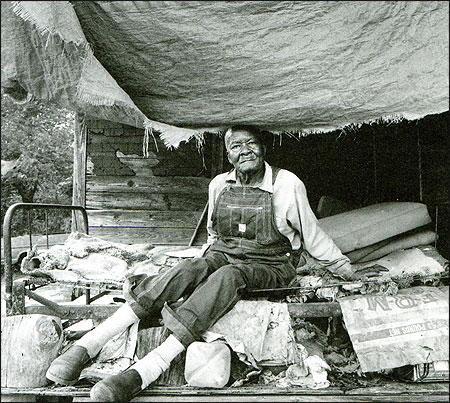

The time also may be right for a return to serious explanatory reporting on unfinished business. There are a number of issues that have not been receiving much attention in the newspapers, magazines or broadcast journalism. One of the most threatening and in a way most shameful of these issues is the persistence of poverty in cities and the countryside and the growing gap between rich and poor that former U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich has said threatens the United States with a “two-tiered society,” with relatively few Americans living luxuriously and many, many others barely making a living or trapped in poverty.

Some believe that by paying little attention to an issue as ominous in its social and political implications as this one, journalists are committing an act of malpractice that far overshadows the handful of sensational plagiarisms and lies and deceptions that get the headlines.

It’s not stated anywhere that American newspapers and broadcast journalists must pay attention to the poor; it is a kind of inherited sentiment—one that once allowed the press to proclaim itself champion of the underdog, comforter of the afflicted and afflictor of the comfortable, with a duty, as one writer said, to “represent the unrepresented.” Practiced with passion by honest and persevering editors, reporters and photographers, the exposure of poverty often has provided journalism with the satisfaction of doing good. In the time of Joseph Pulitzer or E.W. Scripps, it built readership among the laboring poor who could afford a penny or two for a newspaper. Journalists like Dorothy Day, founder of the Depressionera Catholic Worker, or Carey McWilliams, Editor of the Nation, could from their positions on the margin play advocate for social justice for the poor, and champion the downtrodden in the tradition of the abolitionist and muckraking reporters of other eras—and in that way inspire mainstream journalists to make greater efforts of their own.

It’s no longer profitable to expose poverty amid wealth, but there are journalists who still believe that reporting on injustice is at the heart an ideal of American journalism that has lately been overlooked. Newspapers, however, seem to be looking the other way, diametrically the other way, up at their more or less comfortable, highly-paid or mutual-funded subscribers with the suburban cul-de-sac addresses advertisers love to see in the subscription lists.

Important in itself, in an atmosphere of embarrassment over lapses in ethical standards and sound practice, the coverage of the poor also seems to help focus some of the discussion of the need for a clearly articulated “new professionalism” that would clarify journalism’s responsibilities on major social issues, and perhaps push American newspapers beyond what Sandra Mims Rowe, Editor of The Portland Oregonian, has called the “hand-wringing” response to journalistic problems. It also portrays in broader context some innovations of recent years. Even among those who dislike “public journalism” for, as they see it, threatening the integrity of the newsroom by involving journalists in the issues they are supposed to cover, there is a recognition that innovation is needed to win public support for good journalism, and that a responsibility for the creative solution of public problems should be part of that strategy.

Editors may disagree, as MacCluggage does, that poverty and the rich-poor gap are being overlooked, but a conversation with him, as with other editors concerned about the future of good journalism, suggests that problems of this dimension are less likely to be ignored if the newspaper is in touch with readers in active and imaginative ways.

“I’ve seen a lot of reporting about the so-called growing difference between rich and poor,” MacCluggage said in an interview. “…I don’t know if I believe it or not. There are people in need but there seem to be plenty of social programs for them. We’re living in the richest time in our history. We live in an extraordinary time. We report on three of the poorest cities in America, Hartford, Bridgeport and New Haven, but I don’t see much of it in our circulation area. It does show up in our reporting of other issues—impoverished housing, bad schools, crime, drugs, poor health care…”

But MacCluggage, like most editors, knows that coverage of all issues will improve when journalists forge a stronger bond with their communities. When I talked with him, his paper had recently been visited by some representatives of the Freedom Forum’s Free Press- Fair Press initiative, and they had left the impression that confessing journalistic problems to the public was not a bad way to learn about the problems of the communities the paper serves. “What we need to build is a relationship with the community we cover,” he said. Papers ought to consider admitting not only factual mistakes but also “own up to structural problems,” he said.

Among those structural problems some would see the apparent indifference to the poor, or at least a less determined coverage than might have been found in other periods when social issues were pushed to the forefront by protest, government action or press attention.

There are many reasons for the apparent neglect of the issue: the conspicuous villains of the kind that cartoonist Thomas Nast skewered when he was attacking Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed’s shredding of the public interest are today cloaked in respectability; President Clinton has raised the issue of racism, but there is no ringing FDR- or LBJ-style crusade against poverty that would carry journalists out on fact-finding expeditions to dramatize poverty in Harlan County and rural West Virginia or Watts; there are few crusaders in the daily press, certainly not of the stature of Joseph Pulitzer; much of the coverage of poverty has been re-channeled, where it appears in stories on other issues, principally, for many broadcasters and newspapers, crime; some would argue that the tendency to abandon troubling issues is an expression of the way journalists succeed in their careers.

Larry McGill, Director of Research for the Media Studies Center in New York City, suspects that editorial career tracks influence coverage of poverty. Back in the 1980’s he heard reporter J. Anthony Lukas tell an audience that the impoverished “underclass” was not covered by the press “because journalists cover power.” Anyone who doubted that, Lukas said, should look at how editors become editors.

McGill investigated the proposition in a Northwestern University doctoral dissertation and found in a survey of 400 editors that among top newspaper editors who had been reporters, 85 percent had covered politics. The lesson: you don’t get promoted by covering the poor.

As newspapers aim higher on the income scale for prospective readers, the so-called “underclass” drops almost entirely out of sight. Only a truly feisty newspaper will devote much effort these days to a strong series on poverty and only the feistiest will look seriously at the growing disparity between rich and poor, which in some places and in the view of some observers seems to threaten the very existence of the bedrock middle class, a major source of social stability and economic prosperity.

The problem is not resources. Newspaper companies have been doing quite well financially. Nor zeal. More than 1,100 reporters and editors attended the recent annual conference of the Investigative Reporters & Editors (IRE) in New Orleans, and although the top-ten list of investigative stories recognized at the conference contained none specifically on poverty and wealth, clearly there are many reporters and editors who could do a good job exposing the issue.

Several developments in journalism suggest that it is now possible as never before to monitor the situation of poor Americans and find at least some support with a public that professes, at least, to be tired of sleaze and eager for a better kind of journalism.

Through its emphasis on the disaffected, who often live in poorer communities where the local newspaper may arrive at one in five homes, the stillcontroversial movement called civic or public journalism should be able to direct the press’s attention to the unrepresented. The further development of “precision journalism,” called “computer-assisted reporting,” allows statistical information to be studied with ever-greater exactness by reporters and editors who are willing to endure a little training. Phil Meyer, a professor of journalism at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and originator of “precision journalism,” the application of social science research techniques to journalism, said of recent developments using the computer to gather and correlate information, “Precision journalism makes it possible to report on social problems with power and precision. Poverty is among the major issues.”

It wouldn’t be fair to suggest that poverty has been overlooked entirely. Fifteen Pulitzer Prizes for investigation that involved poverty have been awarded over the last six decades, including several in the 1990’s. IRE provided Nieman Reports with a list of more than 170 newspaper, broadcast and magazine projects in the past decade that report on the persistence of poverty in a number of respects, including failures of poverty agencies, misuse of food stamps, poor schools, Medicare scandals and lack of health care, the abandonment of poor neighborhoods by banks and savings and loans, violence in poor neighborhoods, homelessness, devastated families and exploitation of children, corporate squeezing of the poor, and high disease rates, infant mortality and early death among the poor. The list is both a record of journalistic accomplishment and a profile of the persistence of poverty in the United States.

The issue has been put in a constructive context of reform by forthright voices within journalism. At a keynote speech at the 1998 annual Institute on the Ethics of Journalism at Washington and Lee University, Maxwell King, retiring Editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, provided a pessimistic conclusion tinged with hope for a “new professionalism” that would guide journalists back to fundamental responsibilities.

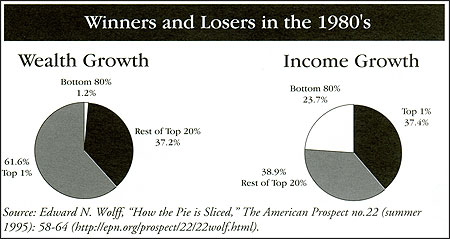

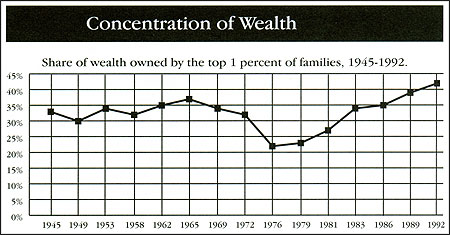

“What does it mean for a democratic society like ours, in which there has been a 25-year trend of the poor growing poorer, the rich growing richer, the divide between the have more and the have-lesses growing steadily?” King asked. “A society in which 45 percent of those filing tax returns in 1993 met the federal government’s guideline definition of working poor. A society in which the richest one percent of the population owns almost one third of the nation’s resources? The United States today has the widest gap between rich and poor of any industrialized nation. How will such a society, already being split along class and capital lines, be affected by a media environment in which the rapidly growing poor segment has little access to relevant information?”

The widening gap between rich and poor is not easily straddled by the daily press, even by newspapers that try to uphold their principles, King said. In spite of efforts to cover the city as well as the suburbs, newspapers find themselves moving with the wealth into suburban coverage. “The economic pressures inexorably push the newspaper toward more detailed coverage of sectors with the sort of demographics that support the effort,” King said. “We have struggled hard at The Inquirer to keep a strong commitment to city coverage, to keep a strong team of reporters assigned to the city, and to provide the sort of neighborhood, lifestyle coverage for the city it so clearly needs. But, frankly, there’s no real comparison; the city neighborhoods and the poorer sectors of our region are getting coverage that isn’t even close to the suburban ‘neighbors’ coverage.”

And it’s not only the newspapers that have migrated. King observed that “the situation is even bleaker when one looks at other media serving the poorer communities: most of the weeklies follow the same pattern as the dailies…. Television and radio, the primary sources of news in poor neighborhoods, rarely cover any community news whatsoever, other than crime and violence.”

John Seigenthaler, an editor of great experience and founder of the First Amendment Center at Vanderbilt University, agreed that “journalists are not looking at the gap between rich and poor,” and implied that the lapse was an aspect of the press’s persistent problem with credibility. He said that the press ought to continue to investigate its values and practices internally and “if these studies dig deep enough they will find that at root anytime the press ignores an issue it robs the public and betrays itself.”

What is needed for the press to direct some steady coverage to the economic polarization of the United States? Seigenthaler recalled the urban riots of the mid-1960’s when poor districts of American cities were the focal points of a continuing national discussion of racism and poverty. “Suddenly we were all on a guilt trip,” Seigenthaler said; editors across the country had to recognize that they “had never paid any attention to the inner city, and as a result there was no constructive reporting of the quality of life. This was a gap in coverage. The ghetto had been ignored.”

Common sense and some knowledge of the complicitous habits of American journalism might suggest that the press could use another political crusade that would justify greater coverage of poverty. Seigenthaler disagrees. Government action should not be needed: “The press doesn’t need political leadership on this issue. It would seem to me that the opportunity would come as naturally for the press in an administration that ignored black candidates for cabinet positions and nominated Clarence Thomas for the Supreme Court.”

Neglect of economic and social problems during the Great Depression should remind journalists that when the press waits for political leadership on an important issue, it may wind up misleading the public. In the early years of the depression the lack of national relief and reform allowed the press to ignore the real consequences of the stock market crash of 1929 and instead to publish palliatives from Wall Street, the White House and congressional conservatives. This lapse, said press critic George Seldes, was the press’s “greatest failure in modern times.” In his book, “Freedom of the Press,” published in 1935, Seldes scolded newspapers for following the Wall Street line.

By following the Wall Street line, journalists wound up deceiving the nation in a way that seemed almost deliberate, he wrote. When the stock market crashed after a series of drops called “technical corrections,” the daily press, Seldes said, “instead of furnishing America with sound economic truth, furnished the lies and buncombe of the merchants of securities, which termed an economic debacle a technical situation, which called it the shaking out of bullish speculators, which blamed everything on lack of confidence. The press accepted the declarations of the President of the United States, a famous engineer, and also the economic viewpoint of the economically illiterate ex-President Coolidge, who blamed 1929 on ‘too much speculation’ and 1930 on ‘dumping from Russia’ and 1931 on ‘the economic condition of Austria and Germany’ breaking down.”

Ignored during this period of paper prosperity and collapse were “American economists who proved that in the boom years there was no national prosperity, that there were two million unemployed; that the farmers were bankrupt, that 30 million of them were suffering; that 71 percent of the population was living on a scale hardly above the margin of necessities. But such economists were considered traitorous radicals in 1928 and 1929; the newspaper would not touch their anti-American ideas or facts.

“Meanwhile the booming industry of advertising kept intimidating the public into more installment buying, kept inculcating the theory of more waste more prosperity, fostered the idea of living-beyond-income and kept up the ‘new standard of living’ by high pressure salesmanship. The nation’s press was party to this achievement of the advertising profession.”

Seldes detected no desire to expose the weakness of the economic system. He found only self-interest: “Obviously just as stores and corporations are the sacred cows of certain smaller newspapers, so Big Business is the great Sacred Golden Bull of the entire press.”

Seldes quoted The Nation, which said editorially that the daily press is unable “to see, hear, or know any evil in advance of catastrophic events which implicate the mighty.”

There is another possible analogy between the journalism of 1929 and the journalism of 1998. About the time of Seldes’s indignant outburst, other critics were daring the newspapers to step out in the open and express clear standards of accountability to the public. Protected by the First Amendment, therefore free of outside interference, the press was accused of practicing a “negative freedom” without clear purposes beyond the protection of profits. This, the critics said, was a form of social irresponsibility. This criticism has been restated recently by some editors as a way of encouraging public allegiance for clear journalistic purposes—even though forthrightness about journalism’s purposes makes newspaper lawyers nervous.

In his Washington and Lee speech Maxwell King said that what was needed is a “new professionalism in which we combine a commitment to issue-oriented explanatory journalism with a bold, aggressive articulation of American journalism’s professional ethics and obligations. This new professionalism would harness the newspaper’s distinctive strength—the capacity to organize, articulate and explain complex issues—to the power of professional ethics.”

King said that during much of this century, “journalists in this country have eschewed professionalism, preferring to rely solely on the power of the First Amendment. In fact, we often have hidden behind the First Amendment’s protection of free speech, taking a legalistic position on our professional obligations.”

He criticized the caution that turns newspapers away from expressing their responsibilities for fear of retaliation in libel cases, where their professed standards might be used against them in court. This “timorous posture” has led to a “relative lack of professionalism among journalists; compared to physicians, scientists, academics and even lawyers, ours is a poorly articulated profession in terms of standards and codes.”

Seigenthaler agrees with King. Like King, he is a critic of public journalism and believes that change in newspapers should come from within the profession in projects such as the American Society of Newspaper Editors’ threeyear investigation of “the root causes of journalism’s dwindling credibility,” rather than through broader social efforts such as those supported by the Pew Center for Civic Journalism, whose involvement with some newspapers Seigenthaler believes has “discredited” public journalism. About the ASNE effort, Sandra Mims Rowe, Editor of The Portland Oregonian, said that the project would be devoted to “long-range actions that can advance our credibility and increase public trust.”

Like Seldes before him, Seigenthaler is uneasy with the optimistic tone of news about the economy. It seems, he said, that “all economic news is good news. It’s not reporting on the economy to say that a corporation has had a bad quarter and the stock has dropped,” Seigenthaler observed. This is an incomplete picture: “In an economy where there’s not much tolerance for the poor, journalists are not looking at the gap between the rich and poor….”

Given that failure of coverage as evidence of shortcoming in professional standards, how do journalists approach the new professionalism?

One way is to practice the old professionalism vigorously. A careful analysis of public or civic journalism that appeared in the winter issue of Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly suggests that public or civic journalism can best be defended as an innovation when its active citizenship and community-rousing efforts are supported by sound, old-fashioned objective investigation of important topics.

An article by Peter Parisi, an associate professor in the Department of Film and Media Studies of Hunter College of the City University of New York, suggested that by encouraging people to think of themselves as citizens, seriously involved in solving the problems of their communities, public journalism “promise[s] an ambitious explanatory journalism on the largest questions of public policy and a journalism rich in features so frequently bemoaned as missing in journalism—cause, context, compassion, background, perspective, issues, underlying structure.”

But the promise is betrayed by another assumption of civic journalism, one that reveals its devotion to sincere good will and seems satisfied with community involvement as a solution to social problems. “In practice, however,” Parisi wrote, “civic journalism retreats from this promise. One might expect that its critique of the cynicism that results when journalistic narratives ignore ‘solutions’ would be to structure reporting around concern for the wellbeing of society. In other words, journalists would not simply report public problems in their dramatic, conflictful outlines, but would ask a variety of sources: ‘What can be done about this social problem?’ ‘What are its causes?’ ‘How have other countries and other historical periods confronted the problem?’ ‘What are the best ideas of contemporary authorities who have studied it?’ ‘What obstacles stand in the way of solution?’…This would produce the long-absent reporting of the news within a framework of cause, compassion, and context.”

Instead, Parisi writes, civic journalism’s proponents seem satisfied to have provoked a community response, even though it may do little to solve the problem.

The phrase “long-absent…” suggests that in their pursuit of new values that might draw attention to poverty and wealth, journalism should try to revive the accomplishments of more successful periods. The importance of personal journalism certainly must be acknowledged, but one noticeable characteristic of any productive period in recent American journalism has been the effective use of the style of reporting that is called “objective.” The criticism of objective reporting as a sterile, power-serving form of reporting has become routine. But seen not as unwanted relic but as one among several indispensable means of observation, it remains a bedrock of investigative and explanatory journalism. The public appreciates its value more than many journalists do, and when it is practiced by a great reporter who respects the hard-won fact, nothing surpasses it. Reporting that is dismissed as being sterile because it is objective often is not objective at all. It is superficial. It’s possible to dislike superficial reporting and be uneasy about its value to citizens without using it to enthrone other not-thoroughly-tested forms that, to an astute analyst like Parisi, have their own faults.

It appears, though this is just a glimmering, that newspaper journalism may be approaching a moment of synthesis, in which a number of recent developments begin to make sense in combination. Maxwell King is another prominent editor who has jabbed at public journalism because members of the movement seem to him to push journalists to “drop your posture of independence, of distance from the civic process, they urge, and join the battle on behalf of the public good.… Unfortunately, in so doing, the leaders of this new movement have rejected—in fact, have scorned and derided—one of the ethical cornerstones of modern American journalism: the neutrality, the independence, of the newsroom.” He suggested that those devoted to public journalism “forget about organizing meetings; forget about activism; do not destroy the independence and neutrality of the newsroom,” and instead join in a new professionalism.

But many editors recognize the value of reaching out to the public in ways that are constructive and not merely ingratiating, and while they may not wish to mobilize public opinion, they see that it is necessary to find ways to build a devoted readership.

Jeannine A. Guttman, Editor and Vice President of The Portland Press Herald and Maine Sunday Telegram, appears to be one of those editors whose paper is joining the outlook of public journalism with the power of objective reporting on important issues. A series in The Sunday Telegram in 1996 suggests as much. It was a thorough piece of objective reporting on the gap between rich and poor in Maine.

Guttman strongly supports public journalism and suggests that when the public is allowed to talk frankly with journalists about news judgment, reporting and editing, stereotypes dissolve and connections are made that increase the confidence of readers and the competence of reporters and editors. The newspaper, she says, must learn to “value all citizens,” and organized contact with readers, or prospective readers, seems to lead in that direction: “When you’re in a group talking to a mother on welfare, you’re talking to a real face, not a stereotype. That’s what’s been missing in our coverage. Until we value all citizens as much as we do legislators, spin doctors, power brokers and lobbyists, we won’t be doing our jobs.”

Of King’s criticism she says, “That’s ridiculous. It does not speak well of the individual journalist to assume that if we get near the public we will lose ethical judgment and besmirch the great institution of journalism.” In the forums that her newspaper has organized, on alcoholism, for example, the paper has reserved the right to withdraw if it finds that its neutrality is jeopardized by public involvement. Members of the public understand this stance.

Through the leadership of then-editor Lou Ureneck the Maine newspapers have been involved in public journalism since 1994, Guttman said. The philosophy of public involvement has, she said, “taken root over time.” The series on the gap between rich and poor seems to be one in which a combination of public involvement and thorough objective reporting has accomplished an important piece of explanatory reporting—not a bad model for other papers.

To complete the series, reporters Eric Blom and Andrew Garber did 200 interviews over five months and used computers extensively. For example, they created a master occupational data base that revealed changes in Maine’s occupational profile. Another data base contained tax statistics that allowed reporters to see the sources of income for various groups.

The paper found that the gap between rich and poor is growing in Maine, with the top 20 percent of Maine households earning 10 times as much as the bottom 20 percent in 1994, up from 8 times as much in 1979. They also found, and reported in individual cases, that corporate profitability is being increased through layoffs that “are eroding Maine’s middle class” and that a “glut” of lower-skilled workers is driving down wages, and that “low-wage, semi-skilled workers overseas are taking the jobs of Maine people.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"How to Make Poverty Disappear"

— By F. Allan HansonAll those who talk about new purposes for journalists ought to keep in mind the fact that they have been discussed before, and in similar terms. Decades-old discussions may yield some answers. To unattached observers journalism must often seem to be comfortably troubled; who but several generations of journalists could spend 60 or 70 years arguing about objectivity, without ever changing the terms of the argument or expecting to settle the question? The staying power of journalistic issues—objectivity or not, pandering to advertisers or not, hiding behind the First Amendment or proclaiming firm principles—is so remarkable that it must appear to the uninitiated that journalists cultivate their complaints as a way of pretending that they’re trying to solve them.

It also may appear that journalists have a hard time phrasing their problems in ways that allow solutions because the profession itself rests not on bedrock but on a shifting ambivalence about nearly everything it touches, including the public, which in journalism’s tory periods is seen as a mob of six-pack slingers, and in periods when Jeffersonian idealism is revived as a font of wisdom.

Ambivalence produces an ethical opportunism that infuriates those who expect journalism to follow a steady vision of social justice and sound public interest. Ethical opportunism allows journalists to grab off important stories without worrying too much about fixed ethical standards, and it also gets them into trouble when journalism oversteps.

Can journalism, so easily distracted, articulate standards that it truly intends to follow? Perhaps most easily when the identity of the ideal individual journalist is under discussion. Here, some of the most inspiring characterizations come from other periods, and even though they may include a touch of bravado, they are worth considering if they suggest how the elements of outstanding professionalism are combined in the pursuit of poverty, injustice and other important issues. In these characterizations the suspect word “conscience” appears frequently, as perhaps it should. Only through the insistence of a hard-working democratic conscience will any journalist ever do a good job exposing the roots of injustice; only the professional conscience will allow the journalist to try to do what has become very nearly impossible: recognize the indispensable importance of seeing in the midst of fragmentation, selfishness and indifference, a whole public interest.

More than 50 years ago Robert Lasch, an editorial writer for The Chicago Sun, wrote in the Atlantic Monthly of the professional conscience that journalists today seem to want to recover and, except for the use of the word “newspaperman” to describe newspaper journalists, expressed himself in language that might have stirred excitement in the ASNE think tank or at the last forum of the Committee of Concerned Journalists:

“The newspaperman’s problem is to reconcile heart and head: to discipline the impulses with an intellectual regard for truth, and at the same time to inflame curiosity with a social purpose. This marriage takes place when he sincerely represents, in judgment, in selection, in emphasis, in the responses of his news sense, the whole people and not any one section or class; and when he devotes the whole of his technical competence to the pursuit of the truth as best he can perceive it.

“Given such a union, differences of approach can be tolerated.” Disagreements among journalists become significant “only when professional judgment gives way to emotional prejudice or to unseemly attachment to a set of preconceived ideas, or to an overweening desire to make good with the front office. One does not ask that the control of news content be divorced from human nature; only that it be free and pledged, in the broadest sense, to the public welfare.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Radical Right ‘Bust’ Feared From Poverty"

— Will CampbellLasch said that a free press requires a free owner, and proposed, in 1946, that the publisher should recognize “that he is selling circulation and prestige, not an economic point of view or service to special interests; and who, above all, recognizes that selling something is not his first obligation at all, but is subordinate to his responsibility to represent the unrepresented. A man who can divorce himself from the associations and outlook that normally go with wealth; a man who can sacrifice even his own short-range interest as a business entrepreneur in favor of his long-run interest as the champion of a greater cause; a man whose passion for the general welfare overcomes his desire to impose his own ideas upon the community; a man of wisdom and humility, character and devotion, courage and modesty—here is the kind of newspaper owner who can make the press free.”

We will scoff and say that not a word of this creed is in the job description of any publisher or broadcast station owner. But if we scoff it’s because we have learned to think that ideals are impractical and unprofitable, because we don’t believe that the public will respect professional integrity or pay for it. But it does suggest that when the next “new journalism” arrives, as it does every 30 years or so, it might have to include publishers.

Even if it didn’t, is there a program of reform implied in Lasch’s description of the ideal journalist? Or in The Chicago Tribune Editor Jack Fuller’s workaday but no less inspiring definition in his speech to the Committee of Concerned Journalists: “To me, the central purpose of journalism is to tell the truth so that people will have the information that they need to be sovereign.” Lasch’s description of the ideal reporter or editor could be achieved often enough to change the business, whether or not she or he practiced civic or public or old-fashioned objective journalism at a serious level of inquiry.

A profession, friendlier with the public but still not identified with the public, itself publicly devoted to the study of important social issues such as the disparity between rich and poor, and most of all devoted to the truth, not afraid of its own inherited ideals—isn’t this a program for credibility?

The real challenge of reporting on poverty is it requires that society be seen whole, as a great body of citizens with common public responsibilities, as, in Lasch’s words, “the whole people.”

We come at last to the question of professional conscience, or simply, of conscience. This is a question best left for last because journalists have a hard time admitting its existence in work devoted to factuality, even though it permeates a profession that likes to think of itself as hardheaded.

But some observers believe that on a question such as the existence of poverty, conscience is precisely the door that needs to be opened. In the absence of political leadership or crusades, journalists may find that the voices raised against social injustice, including persistent poverty, are those of religious or moral authorities who, whatever the temperature of political discussion on the issue, find the persistence of poverty in the United States to be simply wrong.

Charles Haynes, senior scholar for religious freedom at the First Amendment Center in Arlington, Virginia, suggests that the discussion of moral topics in the United States has taken a plunge into division, discord and neglect and that journalists are only among the many who cannot find their bearings on the moral disorder that must beset a society that cannot recognize in a consistent way the wrongness of suffering caused by poverty. “I find a tone deafness among journalists when it comes to religion or morality or conscience,” Haynes said in an interview.

“It’s impossible for most reporters to follow anything if it has to do with conscience,” Haynes said. “We are in sad shape when it comes to moral discourse and understanding the claims of conscience. We can’t seem to get beyond stereotypes.” Reporters and editors, he said, “are not prepared to deal with this kind of discourse when it touches on public policy.”

In the United States, he said, “we are struggling to recover a sense of moral consensus on race, poverty, foreign policy and other issues.” But when religious leaders speak out on poverty, he said, “there’s not a ripple” of press attention, though he hastens to add that religious leaders themselves, who see the world “through a secular lens,” have lost their ability to speak prophetically in a language that “touches the conscience of the people.”

After columnist Murray Kempton died in 1997, Calvin Trillin wrote a tribute in which he said of Kempton: “He had the true reporter’s eye for facts that had to be faced.”

A simple statement, but a simple dedication to the facts that are not immediately apparent, or fashionable or unbearably exciting to the over-excited millions may be the journalistic expression of conscience that the press is looking for as it tries to improve its public standing and do its job.

Michael Kirkhorn was a Nieman Fellow in 1970-71. He has worked for five newspapers, including The Milwaukee Journal, and he has taught at several universities. He is director of the journalism program at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. Through December of this year he will be living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, with his wife, Lee-Ellen, who has a postdoctoral fellowship in nursing research at the University of North Carolina, and with their three-year-old daughter Amelia. He has been working for some time on a long manuscript on the question of the independence of the press and hopes that it might turn out to be an acceptable book.

Michael Kirkhorn was a Nieman Fellow in 1970-71. He has worked for five newspapers, including The Milwaukee Journal, and he has taught at several universities. He is director of the journalism program at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. Through December of this year he will be living in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, with his wife, Lee-Ellen, who has a postdoctoral fellowship in nursing research at the University of North Carolina, and with their three-year-old daughter Amelia. He has been working for some time on a long manuscript on the question of the independence of the press and hopes that it might turn out to be an acceptable book.