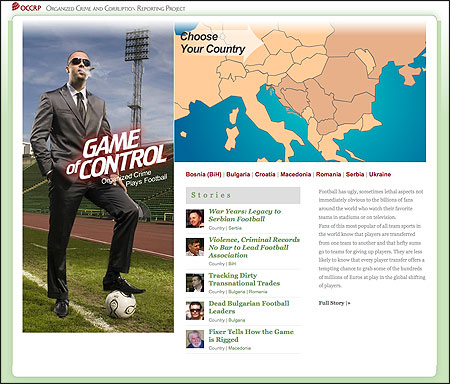

The Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a consortium of investigative centers, brings together journalists on cross-border stories.

In 2000, I arrived in Sarajevo, the tumbledown, war-torn capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. On a brief hiatus from my reporting for The Tennessean, my two-week training assignment seemed straightforward and simple to perform. Sarajevo has always seemed like Roman Polanski's Chinatown—an inscrutable land where bad things happened, and if you asked about them, the explanations seldom made sense. Corruption was rampant. Crime lords with colorful names like Caco (pronounced "Satso"), Celo ("Cheylo"), and Gasi ("Gashi") were local celebrities.

My job was to train reporters, and I figured I could do that without having a clear understanding of the environment in which they work. Or so I thought. Eleven years later I am still in Sarajevo part time advising the Center for Investigative Reporting (CIN), which I started in 2004. I also work as an editor on the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a regional consortium of investigative centers founded to tackle the issue of organized crime.

My thinking back then was wrong in so many ways. My journey from naïve and altruistic trainer to editor who oversees local investigative stories on organized crime has been long and sometimes painful. Altering the perceptions I arrived with proved to be my biggest challenge. It should have been obvious, but it had never occurred to me that American journalism is unique and is only practiced in the United States. It was forged out of our history, culture, politics and economy. While it is a business, its practitioners also have a public service responsibility. Democracy—with its need for a fourth estate to fight corruption, hold government accountable, and educate its citizenry—is intrinsic to our journalism.

RELATED LINK

Resources for Investigative ReportersBut democracy, as we know it in America, isn't yet working here. Consequently, in the Balkans, journalism is a different beast. Those who are involved in journalism act as players in the political process. Most editors and publishers see themselves as serving the political establishment by hosting a dialogue with the political elite about what is best for the country. The idea of serving the public interest is a distant second since unfortunately the public really doesn't matter. Power resides solely (and those who hold it hope permanently) with the political elite so direct engagement with them is seen as the most effective media strategy to bring about change.

This difference in perception changes everything. When the audience and the owners belong to the political elite, not only does it change what stories get reported but it also changes how they are written or produced. Few feature stories about ordinary citizens are done because journalists and politicians regard them as irrelevant. Storytelling and background context mean less to a group of insiders so stories are often unintelligible to ordinary readers. Instead, it is no surprise that most of the Balkan news media tend to feature event-driven political stories about the daily theater of Balkan politics.

Corruption also means something different. Westerners think of corruption as the (often illegal) use of resources for the benefit of the few at the expense of the many. In the Balkan context, what Westerners call corruption is seen as the customary tool of political organization. No one holds the expectation that resources will be fairly distributed. The spoils go to the winners, and therefore people are not trying to change the system. They are trying to belong to it.

Independent Media?

The words "independent media" mean very little in the region. Independent of what, people would ask. In Balkan countries, almost all business is still determined by politics so no one is truly independent. Almost all media—organizations and journalists—have political connections either directly through the political parties or indirectly through oligarchs and organized crime. Political parties sponsor some of them and the ruling party controls state media. The business elite and the politicians operate the advertising market. News media that survive in the region do so not through the quality of what they produce but through the nurturing and maintaining of connections with this elite. A nongovernmental organization like CIN is considered by many to be an agent of foreign powers.

This arrangement undermines journalistic standards in this country and other countries in the region with similar dynamics. If income and credibility are not connected with fairness, accuracy and readability but with political and financial relationships, then the workplace standards don't need to be high.

Rather than being seen as a bad thing, organized crime is seen as just another actor in the political process. Crime figures here are smart in how they build connections to powerful political parties and oligarchs. Some provide inexpensive loans to politically connected businesses, which serve to launder their money and increase their political influence. It can be difficult sometimes to separate who is a criminal, who is an oligarch, who is a politician or, as is often the case, who is all three.

My Training as Editor

When I became an editor and had to work with journalists reporting stories, my real training began. For one thing, communication was an issue. Understanding someone's words did not mean that I understood the importance they held. It took years before reporters really understood what I was trying to say and, in turn, before I could see things through their eyes. Gradually, however, the "Chinatown effect" lost the power of its mystery so that I was able to understand why people acted as they did and, importantly, I became able to predict their behavior.

In the beginning, it seemed as though people seemed to lie a lot to me. I took offense, as many Americans tend to do. But I eventually realized that to survive in a country ruled by one party, people sometimes had to lie to survive. Often it was not expected that the lie would be believed but just accepted.

I also clashed with reporters on stories. What I considered to be a story, my reporters sometimes did not. Politics was news and was seen to influence everything. Few reporters were interested in the plight of minorities, the working poor, and pensioners. Ordinary people were seldom included in stories and how an issue affected them was rarely reported. Instead, members of the political elite set the news agenda and were the ones who were quoted and portrayed in stories.

There were other challenging differences. For example, politicians might squander public resources while enriching themselves but technically their actions were not illegal. As a consequence, many reporters felt this was not a story because the activities were not illegal. I invented the term "legal corruption" to address these cases and change the reporters' perceptions.

Reporters warned me that it would be difficult to get the information we needed to do investigative work. Freedom of information laws are weak in the region. But the bigger problem was that many reporters relied on political parties for their documents and seldom had sources outside of their personal contacts. However, when pushed, they proved very resourceful in getting all sorts of data. I have even come to believe that when a reporter develops the necessary skills it is easier to secure government records in Eastern Europe than in the United States.

Despite the low standards evident in most of the region's news media, the reporters themselves proved to be as adept as journalists anywhere. When given the resources and motivation—and with strict standards put in place—the reporters I have worked with were able to turn out great work that won international awards, even when competing with U.S. journalists.

We still face many problems. Funding for media nonprofits is limited, even though potential donors recognize that nonprofits are the only independent source of news and information for citizens. Given the realities and sensitivities of the elite, many newspapers will not run politically sensitive stories. If reporters write about an oligarch in places like Serbia, Kosovo or Azerbaijan, it is unlikely the story will appear in the mainstream media.

It is obviously very dangerous to report on organized crime. While we have developed sophisticated ways to protect our reporters, sometimes they don't follow these procedures. Such reporting can be done safely but exercising good judgment and sticking to the ground rules is essential.

Where we have succeeded is in bringing together a number of like-minded journalists who have the desire to expose corruption and reveal the activities of organized crime figures—all in an effort to inform the public. The standards remain a little different than in Western newsrooms and often stories don't read as ones done by U.S. reporters would. But given where we started—and where we are today—I would say that our approach is working.

Drew Sullivan co-founded the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project where he served as director and is now advising editor. He founded the Center for Investigative Reporting in Sarajevo in 2004 and still advises the center on a part-time basis.