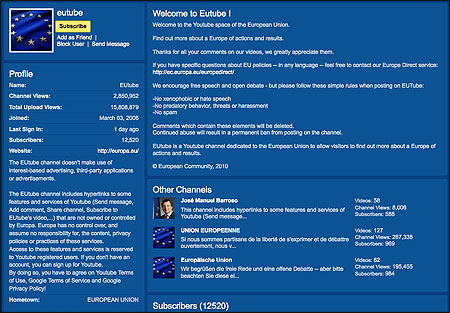

The European Union has invested in technology to deliver its message directly to the public.

At the age of 28, Irina Novakova holds a lofty perch in Bulgarian journalism, covering Brussels as European Union (EU) correspondent for both the most serious newspaper and weekly magazine in Bulgaria. She is prominent among the pack of correspondents from ex-Communist Eastern Europe who try to explain the often bewildering EU to its newly democratic members. Nevertheless, she’s anxious. The economic crisis is roiling the region’s media. Finances are so bad for her paper in Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, that management hit the staff with pay cuts.

In Brussels, meanwhile, recent EU member Lithuania is already down to zero correspondents. The last Latvian fends for survival, and a Hungarian correspondent tells Novakova how his country’s sagging interest in EU affairs may force him to freelance, moonlighting in public relations. A veteran Serbian correspondent whose postwar nation aspires to join the EU laments he might need to leave because no client in Belgrade can afford to pay him to report from there. Novakova has attended several farewell parties where the correspondent departs without being replaced.

This trend, though, is not limited to Eastern Europe. The EU press corps itself is dwindling: According to the International Press Association (IPA) in Brussels, the number of accredited reporters has shrunk from some 1,300 in 2005 to 964 in 2009.

What’s happening in Brussels is part of the same storm system battering the journalism industry globally. The pressure is not only financial. EU agencies are embracing multimedia and using the Internet to deliver messages directly to constituents in what we might consider political spin-doctoring in real time. Back home, some editors think that European affairs, like so many other stories today, can be covered cheaply and easily from the newsroom via the Internet and telephone. Why keep a correspondent in pricey Brussels?

Novakova describes the “sense of gloom” that permeates the press corps. “I wouldn’t call it a crisis or panic but when you talk to colleagues over a beer, they say, ‘What can you do, these are the times we live in?’ ” she says. “There’s a lot of dark humor. It’s a sense of powerlessness that it’s out of your control. Also, that you’re not unique: What has hit the car-making industry or the banking industry in London is hitting us. It’s in journalism. It’s everywhere.”

For denizens of its 27 member countries, what the EU does matters, as does the ability of voters back home to know how and why their representatives make their decisions. With fewer correspondents roaming the halls in Brussels, 500 million or so EU citizens are less informed about the policy decisions that affect their country and about the complex relations their country has with myriad European institutions.

Yet the vast EU public relations machinery—with its Webcast press conferences and well-written press releases along with its slick broadcast-ready video—has devalued, unintentionally, the work these foreign correspondents do in the eyes of consumers and editors alike, says Lorenzo Consoli, IPA president. When Consoli attends a Brussels press conference and asks a probing question, reporters back home who watch and listen on a computer, with press release in hand, can incorporate the answer (and the question, if they choose to) into their stories. Those stories can be published online before Consoli even returns to his office.

Follow this to its obvious conclusion, however, and we have to wonder who will be left to even ask questions? What happens when those who actually do reporting are no longer there?

Especially at times of crisis, such as when European nations this year grappled with Greece’s financial situation, which sent the euro tumbling and EU members scrambling to find a viable solution. At that point, institutional knowledge and connection to reliable sources is vital. Reporters who’ve been covering the story for years are well positioned to dig deep and tell the story with confidence in the validity of information they have gathered.

Without such a foothold, the impulse to cut corners can be strong. That’s when the material produced by the PR folks in Brussels is presented as news. While editors might alter it slightly, the news organization may still present it as original journalism. Especially prone are cash-strapped outlets in Central and Eastern Europe. And not enough readers and viewers are savvy enough to detect the difference.

Changing Rules

Concerned about this trend and with an eye toward reinventing the added value of Brussels-based correspondents, the IPA has called on EU institutions to “cooperate more closely and openly” with accredited correspondents to “promote a more democratic media landscape.”

Here is how Consoli describes the alternative: The idea of bypassing the professional press, getting rid of that filter for information, and speaking directly with the citizens is the totalitarian dream. Public opinion doesn’t ask questions. It is the privilege—and duty—of the press to ask these questions, to challenge officials, and get answers. This is how democracy works. With the Internet and all the new media nowadays, a lot of people are forgetting this.

As part of this push, the IPA made several requests of the European Commission and Council of the European Union as a way for correspondents on the ground to produce deeper, more meaningful stories. The IPA proposed setting up more off the record or background briefings with more candid officials, along with early access to press releases that would be embargoed until correspondents have time to digest and interpret EU actions.

“It’s an acknowledgement for companies that go through the expense of having people here that it’s worth their while,” says IPA vice president Ann Cahill, who is Europe correspondent for the Irish Examiner. “I compete, and I’m happy to compete. But if I can get something in advance, then I’m happy to do that, too.”

European institutions themselves recognize the integral role of Brussels-based correspondents to not only explain the nuances of EU operations, decisions and policies but to shape public opinion, says commission spokeswoman Pia Ahrenkilde Hansen. This is especially true in member states where political forces less friendly to Brussels often sway popular attitudes against it.

“Of course we’re very concerned when journalists leave and their media choose not to replace them,” says Hansen. “We see the importance of having an accredited press corps to capture the complexity of what the EU does and why in a way no one else can. They have a responsibility to provide the public with the information they need to form opinions on their own.”

The commission grants the press corps unique access, says Hansen, with more frequent background briefings for selected correspondents on certain topics. But in meetings with the IPA, she says, EU officials have explained that a general embargo policy would be neither “manageable nor desirable.”

“Operationally speaking, this would backfire,” says Hansen. “We all know leaks happen, but can you imagine if some journalists were favored or if there were no market sensitivity to the subject matter? Some journalists complain that we need to be more transparent, but what would be next—withholding the broadcast of press conferences? Such a policy would be difficult to defend.”

Meanwhile, not every Brussels correspondent agrees with the IPA’s position. David Rennie, who used to write the Charlemagne column on European affairs for The Economist, blasts the IPA for the “privileged access” it seeks, restricting information in the process.

“It’s rank protectionism,” says Rennie, who was based in Brussels while he wrote this column for one of the few publications thriving in these hard times. “In their anxiety to preserve journalists physically based in Brussels, they’re behaving like the worst kind of labor union. What they don’t understand is it won’t work because the forces closing bureaus are more powerful than that. It’s also a direct attack on the media from Eastern Europe that can’t afford to be in Brussels and are trying to cover it from far afield. If you shut off the information, you hurt other journalists.”

Indeed, the real cost is for Central and East Europeans who once saw their nations’ 2004 entry to the EU—and to the NATO military alliance before that—as crowning achievements of their painful post-Communist transition. For the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (joined by Romania and Bulgaria in 2007), membership cemented their break from a totalitarian past and carved out a new place in the Western world.

At the same time, journalists were keen to track their country’s progress in Brussels and hold European and their own officials accountable for their words and deeds. That some have drifted toward having no correspondent based in Brussels who can report in their national language to folks back home illustrates how detached some countries are from the EU.

Changing Appetites

The watchdog role of the press resides at the core of any healthy democracy. For countries that have little or no tradition of democracy, as in Central and Eastern Europe, the absence of the journalist in the broad mix of policy discussions is a troubling trend. Coincidentally, as this region’s investment in EU correspondence wanes, Western Europe seems to have also lost interest in their region, as measured by journalists’ feet on the ground.

When I worked in Budapest during the 1990’s, it was a hopping place for foreign correspondents from North America and Western Europe. Generally speaking, we were there documenting the grand experiment from dictatorship to democracy. Some foreign reporters also used it as a base to cover the wars in the former Yugoslavia, which is Hungary’s neighbor to the south. Today the Hungarian International Press Association (HIPA) serves as a bellwether for Western curiosity. During the last decade turnover in personnel—like me—coupled with tighter foreign reporting budgets and Western disinterest have caused a “steady erosion” of HIPA membership, says Kester Eddy, a longtime member and president from 2003 to 2007. Naturally this affects the coverage the region receives and spills over into the amount and kind of information people have about what’s happening here.

This year, for example, when the fastest growing far-right party in Europe, Jobbik, claimed 17 percent in Hungarian elections, some Western correspondents came over to decipher the phenomenon, as I did from across the border in Bratislava, Slovakia. Understandably the reporting only scratched the surface, says Eddy, who contributes to the Financial Times and The Economist Intelligence Unit. Eddy has done such in and out reporting in the region so he understands the limitations. “If you parachute in,” he says, “it’s inevitable you won’t know it as well as the guys on the ground.”

Novakova understands well what’s happening. When she arrived in Brussels in 2006, at the age of 24, Bulgaria was abuzz. After four decades in which it was perceived as the Soviet Union’s “16th republic,” sitting on the strategic western shore of the Black Sea, Bulgaria was on the brink of joining the European Union. Back then I was writing for The Christian Science Monitor, and EU officials were expressing serious concerns about the entry of Bulgaria and Romania. Upset about the reluctance of their governments to crack down on the worst corruption and organized crime in Europe, the EU attached conditions to their admission.

It was during this stretch that I met Novakova. In 2007, she was taking a one-week break from her Brussels job to participate in a foreign correspondence training I help lead in Prague every six months. (Rennie is a longtime lecturer for the same course.) With Bulgaria’s woes so much in the news, the public there was developing a high level of interest in what was being said about them in Brussels. The intensity of interest peaked when the EU took unprecedented action and suspended aid to Bulgaria in 2008.

As a result, while other national contingents are today pulling back from Brussels, the Bulgarians have climbed from one correspondent, whom Novakova joined in 2006, to seven reporters based in Brussels. Even more interesting, says Novakova, Eurobarometer polls suggest the Bulgarian public now has so little faith in their own government that they trust Brussels more. In turn, the public and thus many editors don’t demand critical coverage of the EU’s maneuverings.

The ones she writes for, however, are more serious minded. So Novakova has devoted significant time during the past four years to comprehending the web of EU institutions, developing sources and schmoozing with key players over drinks. As she’s told me, while EU officials “can chat to you for hours in the corner of the press bar, they would not take your call at all if you are sitting in the newsroom in Sofia trying to figure out what is really going on.”

She feels “lucky” not to be compelled to defend her position or lobby to explain the value of having someone on the ground, as some of her colleagues have had to do. “It’s an existential question at some point,” she says. “To justify that you should keep doing your job—that’s not a nice conversation to have with your boss.”

Michael J. Jordan is a Slovakia-based foreign correspondent. He has reported from two dozen countries and leads the reporting project of the biannual Transitions Online Foreign Correspondence Training Course in Prague.