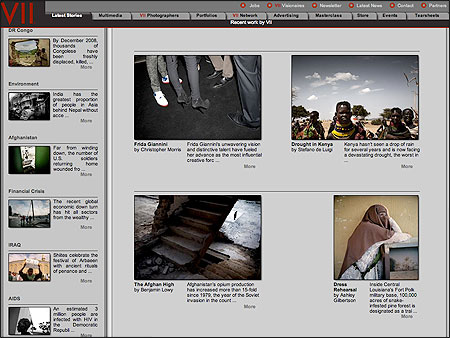

VII uses its Web site to display photographers’ stories at a time when the photo agency is “transitioning from being a mere supplier to being a producer and increasingly acting as its own publisher.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Too Many Similar Images, Too Much Left Unexplored"There is talk about a crisis in journalism, which generally takes the form of angst-ridden journalists, editors and news folk in general asking, “How do we maintain the commercial status quo without which journalism as we know it will be gone?” The question is sincere and extends beyond the fear of losing jobs; there is a genuine concern that the investigative and informative roles of the news media will be lost with a high cost to the civic health of our society.

Interestingly, it’s not a question that I have heard asked by many consumers of news who are finding all the information they want in the online environment—and more. For those of us in journalism, we’re asking it way too late, since a crisis of news communication has been with us for many years, if not decades. From where I sit—as director of VII Photo Agency, a small agency founded in 2001 by leading photojournalists—this digital shakedown offers an opportunity to correct some of the deep problems that have bedeviled the business of print journalism—and gone unchallenged—for too long.

“We don’t know who discovered water, but we know it wasn’t the fish,” said Marshall McLuhan, and so it is with the media. Those who have been totally immersed in news for so long are among the last to discover the true attributes of our medium and it’s taking a major shock to force a reluctant review of what it is we think we’re doing. Far from a crisis, I see this as a major opportunity to redefine journalism with clarity and force as we move into the new millennium. New horizons are opening and rather than look backward in fear we should be looking forward with excitement.

At this point, most discussion accepts that the Internet expands the opportunities for distribution but frets that there is no commercial model to support it. Talk turns to advertising revenues and hope resides on pay walls or subscriptions to restore the balance of readers paying market value for the information they consume. This is, however, a misguided discussion because it overlooks the many fundamental changes in the economics of publishing that have demolished the old structures so completely that we need to think in different terms about our product, its value, and how to monetize it.

The digital revolution is a paradigm shift, not so different from the invention of the printing press, which took exclusive hand-drawn parchments and made the information infinitely available. So it is in the 21st century that the finite resources of print distribution have been ripped apart in favor of the infinite distribution of the Web. It’s missing the point to anguish about the market value of scribes; instead we should be questioning the nature of information and its relationship to those who consume it. We can take comfort in the historical precedent that more money has been made from print than was made from scribing, and so it will be with the Internet.

Once we understand the nature of our product in the digital environment, opportunities will open up as never before.

A Happy Goodbye

I have long had a problem with the old-style editorial market that has consistently underpaid its suppliers, overcharged its advertisers, and given short shrift to its consumers with its restricted content agenda and formulaic presentation styles. I don’t miss the coercive practices and the hours of argument over rights-grabbing contracts offset by derisory day rates and nonexistent expenses. Goodbye to all that.

Gone is our former dependence on the powerful elite who controlled the vast infrastructure of print production and distribution. The artificial economy of supply and demand not only kept fees unrealistically low but also restricted the information available to readers. Ideological and economic powers maintained a stranglehold on what was considered news and only those who bought into this agenda of controlled information were allowed access to the channels of communication. And all too often the credential for entry into this exclusive club was the endless rehashing of tired stories, lazy worldviews, and haughty perspectives.

Now is the time for reinvention.

With the newly emerging Internet tools and increasingly diverse and sophisticated online audiences the opportunities are multiplying as we seek to harness our skills to serve a richer communication mission and to generate more revenue. It’s a moment of great optimism and opportunity for those with ambition and imagination to go beyond what we have known before. While I share the pain being felt by the many individuals and small organizations that are struggling, I don’t have the same sympathy for the organizations that have treated photo suppliers with disdain for so many years. And for those individuals and small organizations that find themselves out in the cold, if we think we have something to offer now is the time to prove it.

For the first time in many years, being small is an asset. We keep hearing that the tested revenue models no longer work for publishers, and that’s true. The bigger you are, the greater your infrastructure and the more you have to sustain while at the same time your ability to adapt is limited. Fixed costs of staff, property and production are overwhelming and legacy contracts are stifling. Investors demand that the big grow bigger at a time when maybe there’s greater profit in smaller operations. At a time when flexibility, adaptability and experimentation are the cornerstones of our business, the smaller we are the bigger our opportunities.

Now is the time to think different.

Consider the monkey trap in which a delicious nut is placed at the bottom of a jar waiting for a hungry monkey to grab it. But the monkey’s clenched fist wrapped around the nut is trapped by the neck of the jar. And here we are, focused on short-term solutions to yesterday’s problems, fixated on the things that used to feed us, desperately trapped by our need to eat as we hang on to a tried and tested formula for survival. And so we starve.

Let go. Move on. All the things that we think will sustain us are killing us. And yet our work still has value, and maybe even greater value in the new environment than in the old. It’s not about finding new ways to do old things, but time to radically rethink our business models by redefining our products, our partners, and our clients. We come from a world that was relatively simple where our product was easily defined—image licenses in various forms—and our relationship to clients was clearly understood as a humble supplier, financed in the largest part by one simple model of advertising-funded publishing.

Redefining What We Do

Fundamental to change is the redefinition of our product. Historically, intellectual property of all kinds has been sold in units to those who consume it or more often to intermediaries who have profited from packaging

and distributing it. Those units have been fees for days worked or licenses measured per use of existing material. Today we are experiencing the pain of oversupply in a saturated market—there is just too much information out there and adding another photograph to the ocean of content doesn’t increase value, it further dilutes it.

Yet the value of intelligent photojournalism is still with us. Rather than struggle to survive on the diminishing prices of licensed units, I have recalibrated my mind to a new way of thinking. I no longer see VII as a traditional photo agency that supplies images in response to someone else’s demand but rather as a powerhouse of integrity and believability; those attributes are what I see as our true product and our value.

In a world where so much information is of uncertain origin or is otherwise unbelievable, believability becomes a highly valuable asset. It’s true that not everyone cares where their information comes from and many search merely to affirm their existing beliefs, but there are enough people in this big wide world who do care to make this a desirable product with real commercial value. And in redefining the product and the value system I find that there is already a market with cash to spend on something they want to believe in.

Just as it’s necessary to redefine our product, it is also important to redefine our relationship to the marketplace when it is no longer relevant to think of us being in a simplistic two-way relationship as suppliers to clients.

One of the exciting aspects of business in the 21st century is the more complex mix of components with expanded opportunities for distribution and funding. Instead of clients I look for partners, often more than one. Instead of fees, I look for shared investment with open-ended (and hopefully extended) returns. Most importantly, in a world that is awash with too much information and too many images, I am moving away from licensing images with ever-diminishing fees. Instead, I am starting to monetize other attributes.

For VII Photo, our most valuable asset is integrity—the credibility of the photojournalists who own the agency, for which I find a growing list of interested partners. Certainly the magazines are still in the mix, but now they are seen more as print distribution partners than as exclusive clients, with additional distribution through TV and online partners. And this arrangement is often cofunded by another party and supported separately by technology partners. The lineup shifts for each project, and as each new partner comes on board the opportunities to do interesting work and to generate income multiply.

Now is the time when VII is transitioning from being a mere supplier to being a producer and increasingly acting as its own publisher.

Fixating on the money photojournalists can generate from old-style transactions is a losing cause. It steals from us the energy that we can use getting busy reinventing the very nature of the product that we are handling. As we do this, the process will allow new values to emerge and a new economy to grow. It is a huge challenge and a fantastic opportunity which embraces all areas of professional journalism as well as citizen journalism, blogging, tweeting and instant, infinite distribution. Some of the key words and concepts that demand interrogation as we act include information, editing, curation, integrity, believability, distribution, journalist, reader and indeed news.

How each of us meets these challenges becomes personal. We can no longer hide behind the failings of the top-down institutions that have controlled information. Now, the future rests in our hands.

Stephen Mayes is director of VII Photo Agency.