At a time when we are increasingly understanding the world through art and images, the journalists who make sense of visual culture are facing a critical moment of generational change and insecurity.

As media companies continue to shed journalists—about 1,000 in one recent week—making the case for arts writing is as challenging as ever. Indeed as we prepared to publish this article, my own job was eliminated by the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel as part of a system-wide downsizing by Gannett.

The job of discerning what’s genuinely artful, what’s worthy of our collective attention—the job of art critics and writers—has never been more relevant

“I’ve lost over 100 colleagues to layoffs in my career,” tweeted Jeneé Osterheldt, a writer for The Boston Globe, who explores culture and politics broadly, including visual art. “I wish that was an exaggeration. And the erasure of diversity, culture, copyediting, and the arts in journalism isn’t just scary. It’s dangerous.”

It isn’t just that the art world has changed, with a proliferation of biennials, long lines for Instagrammable art shows, and mind-boggling art market records. It is that art’s place in the world has changed, too. The planet at large is generating visual culture on a scale that is hard to fathom today. The once-rare tools of the artist are now ubiquitous, a swipe or a click away, in so many hands, and while not everything spilling through our social feeds is art, some of it actually is.

The job of discerning what’s genuinely artful, what’s worthy of our collective attention—the job of art critics and writers—has never been more relevant. While I was the 2017 Arts & Culture Fellow with the Nieman Foundation for Journalism, I invited my peers in the field to take an online survey about the priorities and pressures of their work.

We received 327 responses from visual arts writers and critics. They work for daily newspapers, alternative weeklies, magazines, digital journals, and websites in the U.S. and work from more than 100 cities in 38 states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia, as well as more than a dozen countries.

The survey, conducted in the summer of 2017, included more than 100 questions, some of which replicate those of a seminal 2002 study done by the National Arts Journalism Program at Columbia University, under the leadership of András Szántó. That earlier study, which focused solely on visual art critics, provided a rare opportunity for comparison over a period of upheaval for both media and culture.

Related Reading

Much has changed since then. I remember taking that earlier survey, when Google was in its infancy, Facebook and Twitter still in our future, and rounds of newsroom buyouts less perennial. The large majority of respondents worked for daily newspapers then, while less than a third of the current group do. Indeed, nearly half work for web-only outlets today, many hustle to write for multiple publications, and nearly a quarter are running their own, independent platform, at least part of the time, according to the new numbers.

The new survey points to an optimism about the art that’s being made today and a belief that the definitions for art are expanding. Art beyond the art capitals of New York and Los Angeles is increasingly important, as are artists addressing issues of race, gender, and identity. As for influence, it’s concentrated in the hands of veteran critics, a small cadre of mostly white men based in New York City.

In May, I teased out a few findings for Nieman Reports. I wrote about an emerging vanguard in visual arts writing, publications, projects, and individuals producing some of the most promising and inventive work today. I also highlighted the rise of Hyperallergic, the for-profit blogazine founded by Hrag Vartanian and Veken Gueyikian, which today rivals the arts journalism of legacy media, according to the survey. It was the only digital newcomer to top a list of publications well-regarded for criticism.

At this moment of transformation, what follows is my read on some of the topline takeaways from the survey, the data for which I’m sharing so others can dig in as well. Some will doubtless draw additional conclusions.

Pressing Issues

Art is often a lens through which debates that occupy the country—about race or gender, for instance—are seen. It may begin with a single artwork, an artist action, or a social media thread, but many art-world discussions have a way of becoming national debates. One sign of generational change is the degree to which arts journalists today are willing to write at the intersection of art and politics.

Several art-world controversies unfolded in the months leading up to our survey. Some called for the removal from the 2017 Whitney Biennial of a painting by a white artist that depicted the body of Emmett Till, a black teenager who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. Dana Schutz’s “Open Casket” is based on a galvanizing civil rights-era photograph of the 14-year-old’s mutilated body in his casket. Some suggested the artwork could not be divorced from the violence people of color face today and criticized the reiteration of the original image as callous.

Similarly, Native Americans and others accused the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis of trivializing the hanging of 38 Dakota men by installing Sam Durant’s “Scaffold” on its grounds. The large, outdoor sculpture included representations of the gallows used in the mass executions by the U.S. government in 1862. And, of course, memorials and monuments to Confederate leaders are a flash point for debates about racism and white supremacy.

From the Archives

Critical Condition: Why Professional Criticism Matters

“If you are counting full-time critic jobs at newspapers, you may as well count tombstones.”

In the Winter 2013 issue, Nieman Reports explored why professional criticism matters, including contributions from Paola Antonelli, Brett Anderson, Maria Popova, and others

Art institutions are trying to keep up. While museums have talked about inclusivity for years, many are working at it more urgently in the political climate of Black Lives Matter, Time’s Up, and the protests at Standing Rock, rethinking what they present, whom they hire, and how the story of art gets told in their galleries, for instance. The movement to decolonize museums, to rethink how work by some groups is presented, has been covered widely, from The New York Times to Teen Vogue to Vice.

“What we’re learning in real time along with the rest of the world—and hoping—is that this really is a turning point in history,” says Marcelle Polednik, director of the Milwaukee Art Museum. “I think this moment in time is a very significant one for us… in terms of how it’s shaping the future of art history and the future of museum work.”

In this moment of cultural reckoning, it makes sense to ask whether arts journalists have the competencies to engage with such issues and artworks, formally, culturally, and politically. Are the most relevant writers on art today those with the salaries and staff jobs? Do they come from the ranks of traditional arts journalists?

What we do know is about a third of the arts journalists who took our survey write in a way that touches on politics regularly, while a healthy majority do so at least occasionally.

About a third of the arts journalists who took our survey write in a way that touches on politics regularly, while a healthy majority do so at least occasionally

It is the kind of writing that can capture a larger audience, too. When The Washington Post’s art critic Philip Kennicott, who often writes about art and politics from his perch in the nation’s capital, reviewed the portraits of Barack Obama and Michelle Obama, by African-American artists Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, respectively, his review snagged a million sets of eyeballs. While that might have been a peculiar case, a particularly potent convergence of art and news, the audience size was unheard of for the arts team, says Christine Ledbetter, who was the Post’s arts editor at the time. While traditional reviews tend to have small, loyal readerships, reviews or essays that address broader political issues tend to hold meaning for a broader audience, she adds.

The list of artists that arts journalists care about is also revealing. We asked survey respondents to name up to three artists that they believed were worthy of championing. The result was a very long list of more than 400 artists. Only about 30 of those artists were mentioned more than once, a function perhaps of respondents in a lot of places naming artists in their own backyards. Still, while there’s little consensus about specific artists, many of the artists on the list have something in common: they tackle thorny, political issues through their work.

While this list shouldn’t be considered a ranking, artists who came up more often than others, as a group, are illustrative. They include Postcommodity, a collective based in New Mexico and Arizona that installed massive scare-eye balloons across the U.S.-Mexico border a few years ago, bringing an indigenous perspective to the immigration debate; Kara Walker, who is known for mural-sized, black cut-paper silhouettes that explore racial stereotypes; Anicka Yi, who creates esoteric, gender-and-science-related experiences; and Kerry James Marshall, whose paintings are known for exploring black subjects typically left out of the art historical canon. Hank Willis Thomas, whose work leverages branding aesthetics to address issues of social justice, is also in this group, as is LaToya Ruby Frazier, whose photographic projects explore black life and social inequality, particularly in America’s small towns. Postcommodity, a collaboration between artists Cristóbal Martínez and Kade L. Twist, describes the collective as “a shared indigenous lens,” while Walker, Marshall, Thomas, and Frazier are black artists. Yi is Korean-born.

These artists represent quite a contrast to 2002, when Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, quintessential postwar heavyweights—and white men—were the favorite living artists among art critics. The earlier survey posed the question differently, though, asking respondents to indicate how much they liked specific artists rather than asking them to name artists.

This is probably a good time to state an unsurprising finding: The field of arts journalism remains mostly white. About 60% of those who took our survey agreed to answer a question about the race/ethnicity that best describes them. Of those, 167 identified as white, four identified as black, five as Latino, six as Asian, and 20 additional respondents described other or mixed ethnicities. Our highest-paid colleagues, the fewer than 20 people who reported making $80,000 or more, are mostly white men, too. Not a lot has changed since 2002, when the field’s lack of diversity, including among the then younger generation, was highlighted.

So what are the implications of a mostly homogenous field of arts writers? What is the cost to the culture of having the top jobs and much of the influence in the hands of a few white men?

Many of the artists on the list have something in common: they tackle thorny, political issues through their work

The Nathan Cummings Foundation and the Ford Foundation began a new collaboration recently called Critical Minded, intended to support the work of critics of color writing about all artistic disciplines and broadly about culture. Last May, Elizabeth Méndez Berry, of the Cummings Foundation, wrote an important essay about the project, making the case for what’s at stake when so many of our salaried critics are white and male. I’ll let her speak to the issue: “While some white critics write thoughtfully about non-white aesthetics, too many enforce white aesthetic supremacy. The notion that only works emerging from European traditions are worthy of contemplation and celebration still shapes what is covered, what is held up as exceptional, and what is rendered invisible.”

One of her most important arguments was that white artists need to be covered by journalists of color as well. “Critical Minded exists to support ecologies of aesthetic excellence that are not predicated on the white gaze,” she says.

While we attempted to be as inclusive as possible in our invitation, there are writers on art who may not be represented in this survey for any number of reasons, including because they do not identify as arts journalists.

One of the most insightful writers on the Schutz controversy, for example, was novelist Zadie Smith, and the Globe’s Osterheldt is an important voice on art, despite having the broader title of culture writer.

The Most Influential Critic

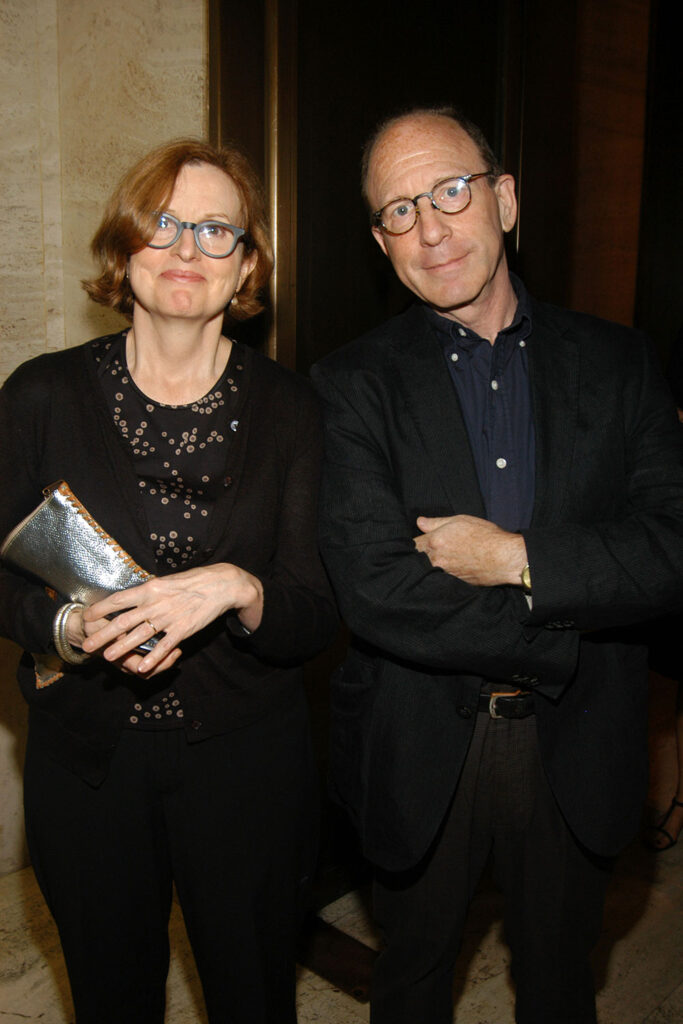

The art critic who holds most influence in the U.S. today, according to her peers, is Roberta Smith, co-chief art critic at The New York Times. Survey respondents were invited to name up to four critics whom they considered “most influential,” and more than a third named Smith, considerably more than anyone else.

Smith is known for her unsparing but generous criticism and for promiscuous interests, especially ceramics, textile art, visionary or so-called outsider art, design, and video art. She’s been writing about art for more than 45 years and views her job as “getting people out of the house,” making them curious enough to go see art, according to her bio at the Times.

While the survey didn’t define influence, the consensus about Smith is presumably, at least in part, a recognition of her work. That seems significant, given how rarely female art critics are so celebrated. There was some lamenting when the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for criticism went to Smith’s husband, New York magazine’s senior art critic Jerry Saltz, rather than to her, some even likening the loss to Hillary Clinton’s in 2016.

Margaret Carrigan was among the first to weigh in for The Observer: “I wake up most days and think at least once, ‘What if Hillary had won?’ Today I woke up and thought, ‘What if Roberta had won?’” A headline in The Art Gorgeous read “The Hillary Syndrome: Everyone Thought Roberta Smith Should Have Won The Pulitzer,” while another in The Guardian read “Congrats, Jerry Saltz – but when will a female art critic win a Pulitzer?”

For our question about influential critics, more than half of the mentions went to just six writers

It’s a fair question, and it’s been a while. Richard Nixon was president the last time a female visual art critic won the Pulitzer for criticism. That was Emily Genauer in 1974, the second year the prize for criticism was awarded, for her writing for the Newsday Syndicate. Manuela Hoelterhoff snagged one, too, in 1983, for writing about a broad range of subjects, including art. And Jen Graves, the former art critic for The Stranger, was a finalist in 2014.

Smith got her start accidentally, writing a fiery rebuttal to a piece in Artforum about Minimalist artist Donald Judd. She joined the Times, where she had freelanced for a while, in 1991 and wrote for The Village Voice earlier in her career. She is also the first woman at The New York Times to hold the position of co-chief art critic.

Who Holds Influence

Beyond Smith, the most influential critics are veteran voices, mostly white men based in New York City. It should be noted that, for our question about influential critics, more than half of the mentions went to just six writers. Smith was the only woman in that top tier. And while a majority of the survey’s respondents were women—who are generally less likely to hold staff jobs and more likely to believe they are expendable—few of them were well ranked in terms of influence. Jillian Steinhauer, former senior editor of Hyperallergic and now herself a frequent contributor to The New York Times, and Carolina Miranda, an arts writer for the Los Angeles Times, were the women ranked behind Smith.

In that very top group of six, Saltz, known for ardent and engaging writing, as well as social media showmanship, was ranked immediately behind Smith. The Pulitzer board praised him for “a canny and often daring perspective on visual art in America, encompassing the personal, the political, the pure and the profane.” Others in this august group are Holland Cotter, the other co-chief art critic at The New York Times; Peter Schjeldahl, art critic at The New Yorker; Ben Davis, national art critic for artnet News; and Christopher Knight, art critic for the Los Angeles Times.

Except for Davis—an outlier in this pantheon, and more on him in a moment—all of these critics have been writing about art for more than 30 years and work for legacy publications, many with long traditions of publishing art criticism regularly. Schjeldahl is the most veteran among them. He’s been writing for more than 50 years. This indicates that influence may be accrued and tied to the reputation and reach of a critic’s publication. Except for Knight, notable as the only West Coast critic and perhaps the only one writing for and about a local region, they are all also based in New York, a critical proving ground for the art world.

Davis is the only critic in this top tier working for a web-only publication, and he’s been writing for fewer years, about 15. Among his peers, he’s known for trying to make sense of the more image-driven arts writing of the internet era, what he calls “post-descriptive” criticism, and his much-discussed collection of essays “9.5 Theses on Art and Class,” published by Haymarket Books in 2013, was nominated for Best Work of Criticism by the International Association of Art Critics. Davis, who got his start at a community newspaper, the Queens Courier, and has written for a range of publications including The Brooklyn Rail, e-flux, The New York Times, and Slate, is currently working on a book about artistic appropriation.

Independent Voices

It’s worth noting that the question of influence was specifically about critics, and those who made it to the top of the list do carry that formal title. What happens to this ranking when those who’ve been writing for more than 25 years are removed from it may hint at what’s ahead for art criticism—including more women, more critics of color, and wider ranging purviews.

These writers don’t fit the mold of their forerunners. They are as likely to write about a cat video festival … as they are to engage artworks on a museum wall

Some of the less veteran voices in the mix—in addition to Davis, Steinhauer, and Miranda—include Hrag Vartanian, editor-in-chief and co-founder of Hyperallergic; Claire Bishop, an art historian, contributor to art publications, and author of “Artificial Hells,” an overview of participatory art practices; Hannah Black, a conceptual artist and writer known for challenging the Whitney Museum of American Art for exhibiting a painting that depicted Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black youth lynched in 1955; Paddy Johnson, founder of Art F City; Andrew Russeth, co-executive editor of ARTnews; Claudia La Rocco, a poet and critic with a special interest in performance; Antwaun Sargent, an arts writer focused on black contemporary art; Hito Steyerl, a philosopher, filmmaker, and author of “Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War”; and Maggie Nelson, a MacArthur “genius” known for vulnerable, personal criticism that she sometimes calls “autotheory”.

These writers don’t fit the mold of their forerunners. They are as likely to write about a cat video festival (Steinhauer), neoliberal capital (Steyerl), or the history of death cultures (Black) as they are to engage artworks on a museum wall. Most write more broadly about culture and society, addressing ideas that surface through contemporary art. Some explore the ways visual culture is reshaping our lives.

“If you look at the veteran critics list and then you look at this other list, the first thing that comes to mind is the word ‘nontraditional,’” says Steinhauer. “I feel like the veteran critics all have these staff jobs and fill this sort of old-school critic role.” The latter group, she said, offers a “much more varied picture of what criticism can be and can do.”

“They are largely independents who have carved their own niche,” says Charlotte Frost, a scholar of digital art criticism and executive director of the London-based gallery Furtherfield. “But that’s where art criticism originated from,” she adds, noting that the earliest critics were similarly independent writers with multiple expertises. “So it’s a return to tradition or origins in some sense.”

The Trump Effect

Given the interest in politics among arts writers today, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the election of Donald J. Trump had an impact on the profession. I decided to add a question about Trump’s election at the last moment, after talking with a colleague who told me she was recommitting to her job after he had won the presidency. The survey reveals she was not alone. Trump’s election changed the way many arts journalists feel about what they do. This was true for journalists across the spectrum of experience, from veteran writers to those entering the field, according to the survey.

It should be noted, too, that we are a very liberal bunch. Of the more than 200 arts journalists willing to share information about their personal politics, more than eight in 10 identify as either liberal or progressive. In fact, arts journalists were more likely to vote for the Green Party or to describe themselves as “other” than to vote Republican in 2016.

Of those who’ve reframed their thinking in the Trump era, many were willing to elaborate at length within the context of an anonymous survey.

“I am more aware of having to defend the arts as key aspects of personal freedom,” wrote one respondent, a full-time staff writer at a website.

“I have always known that I write to build creative community, to support makers…but I have become more conscious of the need to give people who feel silenced, isolated or shut out a place to speak…” wrote a freelancer for regional publications.

Trump’s election changed the way many arts journalists feel about what they do

“A democratic society thrives on a diversity of opinions, a healthy tension between ideas, free expression, and open debate—all attributes, I feel, of the best of contemporary visual art,” said an editor and writer.

A staff reviewer for a major newspaper wrote, “It has made me look at art (even historical art) with more of an eye to political climates and conditions, sometimes at the expense of being able to focus on and appreciate other aspects of the work the way I could before… It’s also made me more impatient with some art-world rituals that are tied to social and market forces.”

“The election of Donald Trump made it seem more futile when I write strictly about art, but in a way, it’s also reiterated the importance of things like art, and contemplation, and the ability to just enjoy something, or think quietly, or talk to people in an open way,” wrote a freelancer working for an arts publication in Florida.

Of the respondents who answered the question about Trump’s election, many also felt that Trump’s presidency should have no bearing on their work. Here’s a pretty typical example of what these journalists had to say: “Artists and art writers have no advantaged perspective on what to do about Trump. I stick to what I know.”

Job Insecurity

Conventional wisdom in recent years suggests that visual arts journalists, particularly critics writing for print and mainstream audiences, are increasingly rare, the dodo birds of the art world. End-of-an-era talk has become commonplace, one of our favorite pastimes. In a typical example, art critic Deborah Solomon offered up a “little prayer for art critics” on WNYC radio in 2013. Describing critics as bossy and easy to hate, she reported what she believed to be a sorry fact: that there were only 10 full-time art critics left at newspapers and magazines in the U.S. That same year, Johanna Keller, who founded the arts journalism program at Syracuse University, said: “If you are counting full-time critic jobs at newspapers, you may as well count tombstones.” Referring to print jobs in particular, Saltz, echoing his wife, Smith, suggested in 2015 that there were “these last 20 jobs left in the United States” and that “they’re going to be gone.” In a more recent interview with In Other Words editor Charlotte Burns, Saltz said: “I’m a dying breed. Critics are a dying breed.”

A lot hinges, of course, on how one counts and defines critics, or arts journalists more broadly, for that matter. Some count only those who are full time or on staff, without some kind of a hybrid beat like my previous one as art and architecture critic for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Others are primarily interested in those with the “critic” title and who write mostly formal reviews.

While the survey was not designed to provide a definitive headcount, so to speak, it does suggest that arts journalists may be less rare than some imagine, which is not to suggest losses are not real. When the 2002 survey was conducted, most major general-interest news publications had at least one visual art critic, though there were notable exceptions, including one of America’s largest newspapers, USA Today. Also, the odds of a publication having a critic dropped for lower-circulation publications then. Again, the 2002 survey looked at a more tightly focused group of traditional art critics, and Szántó and his team identified 230 of them. We don’t need data to tells us that jobs and coverage have been squeezed and eliminated since then.

The survey suggests that arts journalists may be less rare than some imagine, which is not to suggest losses are not real

Still, the field is gathering new voices. Arts journalists who’ve been writing about art for a decade or less but who’ve made it past the two-year mark represent 47% of our survey’s respondents. More than 75 individuals in more than 20 states described themselves as the “chief art critic” or equivalent for their publication. Of those, more than 25 hold a staff position at a newspaper, a count that’s incomplete because we know some newspaper critics didn’t take the survey.

With that said, arts journalists believe their beats are at risk. Most of the survey’s respondents felt moderately secure in their jobs, at best. For those that have some kind of a formal position, a third thought their media organization would not make a priority of replacing them if they left, and only about one in 10 believed it would be a “great priority.”

About 30% of respondents have been writing about art professionally for more than 20 years. And while such lengthy tenures point to some stability in the field—it may also indicate a lack of opportunities for advancement. Consider that less than a third of the survey’s respondents pursue their work on a full-time basis with a staff position. About two-thirds are freelancers, many of whom work for several outlets and the vast majority of whom are working without a contract. For those who do have staff jobs, fewer than one in 10 felt “very secure” in their positions. A third of all respondents report that their jobs are “not at all secure.”

Income patterns tend to reflect employment patterns. The majority of arts journalists—60%—make only half of their total earnings or less from their arts writing. More than half make $20,000 or less a year. This raises serious questions about who has access to our field and who can afford to work for such wages. One of the critical questions facing the profession is how to support the work of cultural writers in a sustainable way.

Art Today

In some ways, the survey was a referendum on the internet and what it’s meant for art. A large majority of arts journalists believe that the definitions for art have expanded since the rise of the internet. They also believe their audiences are both more informed—and confused—about art in the digital era, that society is oversaturated with images and the art world overpopulated with art.

On the whole, though, arts journalists are pretty optimistic about the art being made today. Most believe artists are breaking genuinely new ground. About eight in 10 respondents said most of their work is focused on the art of today.

While some believe we’re living through the most exciting time for art, almost as many say the glory days have faded

Indeed, a majority of arts journalists are proud of the work that’s been produced in the last 25 years, much as those in 2002 were proud of the art produced in the quarter-century before that survey. Nearly a quarter of the survey’s respondents even believe we are witnessing a “golden age” of art today, slightly more than believed so in 2002.

But there is another side to this coin. While some believe we’re living through the most exciting time for art, almost as many say the glory days have faded. More than 20% of respondents believe that “there was a golden age of American art and it has passed.” Moreover, the overwhelming majority rejects the idea that we’re witnessing a golden age—75% dispute this, and 30% do so strongly.

When it comes to the artists we care about today, many of them are working outside the art capitals. More than half of the artists worthy of our ink, so to speak, exist beyond New York and Los Angeles, according to the survey. Some of those artists also create work rooted in or about off-center geographies, like Postcommodity on the border.

Arts journalists have also grown more bleak about the impact of money on art. More than half say the art world is too dependent on the market and commercial institutions, and more “strongly agree” today than did in 2002, a leap from 29% then to 51% today. A small minority—about 16%—disagree, and most of those only “somewhat.” And while the contemporary art market continues to set records—including a recent auction record for an artwork by a living artist, David Hockney, which sold for a bit more than $90 million—a significant majority of arts journalists don’t cover such things. Only 10 people said they report regularly on the market, auctions, and collectors.

Recasting and Connecting

Arts journalists are covering a very different world today. When the 2002 survey was conducted, writing for a web publication wasn’t even a consideration and there wasn’t a real-time discourse driven by hearts, likes, retweets, and hashtags. Most of the 2017 respondents believed the internet had changed criticism in meaningful ways, and younger journalists were even more inclined to say so.

As I’ve been writing these last paragraphs, artists and activists with the group Decolonize This Place have staged demonstrations at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, protesting the presence of Warren B. Kanders, owner of the company Safariland, on the museum’s board, after reports that the company’s tear gas canisters were used against migrants and asylum seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border. The flow of images and insight that led to this protest was swift, from wrenching and viral images from the border, including a mother and her daughters being teargassed, to reporting by art sites like Hyperallergic to online organizing around a hashtag to a highly Instagrammed protest at one of the nation’s most august museums. A poster created for the protest by Decolonize This Place and the collective MTL+, done in the style of an Andy Warhol screenprint, replicates images of the canisters and is made in the fashion of an advertisement for the Whitney’s blowout Warhol retrospective, of which Kanders is listed as a significant contributor. Now, images of the poster are free to proliferate, too.

As ARTnews reported, protesters “implicated Kanders’s involvement in the Whitney within larger global histories of colonialism, queer erasure, gentrification, class struggle, and violence.”

In such moments, visual literacy, news literacy, social justice, global politics, and art become part of a rapidly moving whole that arts writers and critics contribute to and respond to. With audiences speaking so directly to art institutions, this raises questions about what the role of arts journalists can and should be.

As we consider this question at a moment of generational shift—as those who hold influence prepare to leave the field—the survey’s respondents offered up some important self-critique. Many are critical, for instance, of the field’s focus on high-profile artists and exhibits at the expense of other deserving artists and issues. A large majority of the journalists, across age groups, agreed on this point. They also believe that the field as a whole is focused on the art centers of New York and Los Angeles at the expense of deserving artists and issues in the rest of the country.

These critiques and others mentioned in this article raise lots of questions about the future. While most of the survey’s respondents believe what they do has an impact on the art in their region, one might ask what will become of local and regional critics working outside the heat and energy of the art capitals, not to mention the artists they cover. Also, if new competencies are called for today, are there new pathways into the profession? Where should hiring editors be looking for new voices? Will we look back in another 15 years to see a field that remains mostly white?

Arts journalists have the capacity to form narratives, shape canons, set cultural agendas or, at least, to inspire curiosity and “get people out of the house,” as Smith put it

It’s also worth asking this: What will be the fate of the traditional art review amid all of this change? Respondents were lukewarm on the idea that critics are doing a good job of championing artists who will be seen as important in the future. While most agree, less than 5% do so strongly. As our focus is being recast, what—and who—are we not paying attention to?

Arts journalists have the capacity to form narratives, shape canons, set cultural agendas or, at least, to inspire curiosity and “get people out of the house,” as Smith put it. With the relevance of our work on the line and a lot at stake just now, we should confront the questions facing our field—and the pressures on it.

Can we benefit by engaging each other? Most of the survey’s respondents voiced interest in participating in a Listserv community or a similar forum for discussing the priorities and pressures of our work. If you would care to participate or have a hand in shaping what this might look like, please email me at marylouiseschumacher@gmail.com.

Download the full survey results here.