Since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, five journalists have died and at least 10 have been injured as of March 28, according to Reporters Without Borders, an organization that promotes press freedom around the globe. On Mar. 23, Oksana Baulina, a journalist from The Insider, a Russian investigative outlet, went to film a bombed-out shopping mall in central Kyiv shortly after the explosion. While she was there, the Russians hit the same spot again. She died along with the civilian who had accompanied her.

Eleven journalists have been threatened by the Russians, five have been shot at but not killed, and six have been kidnapped, reports the Kyiv-based Institute of Mass Information, a non-governmental organization that works at the intersection of media and civil society. Some of them were released, and the location of some of them is still unknown. There have been four attacks on editorial offices in different regions of Ukraine. Russian FSB agents raided the homes of four journalists with Melitopol’s MV-Holding, detained them for several hours, and seized computers. Ten TV towers have been fired upon, and the Russian military has turned off the broadcasts of six TV channels. Seventy media organizations have stopped their work because of the invasion.

Many journalists and editors were psychologically unprepared for the fact that the war came to their home. Some of them decided to take up arms and went to fight; some became volunteers; some left the country.

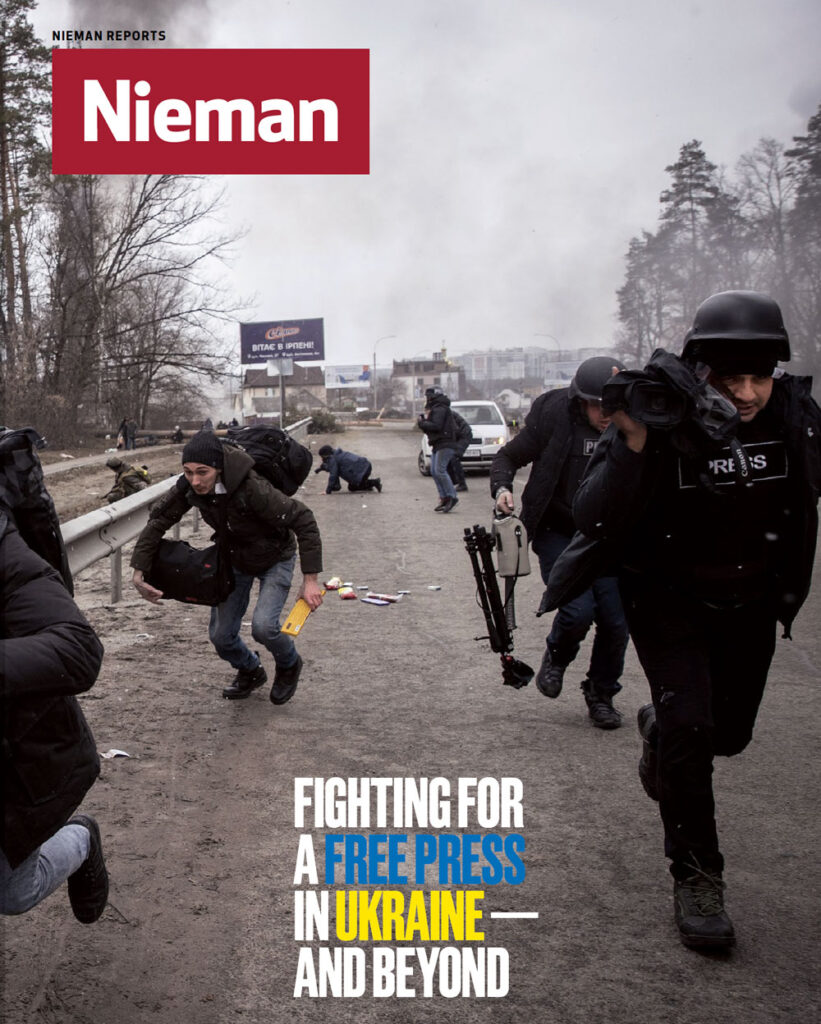

Prior to the invasion, most journalists in Ukraine had no experience with working in a war zone. Only a few dozen correspondents worked in the Donbas, a territory controlled by Russian-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine where fighting has been taking place for the past eight years. Few had security training or protective equipment — bulletproof vests and helmets with "Press" patches. Only some had an understanding of cybersecurity risks, mostly those who worked in the occupied territory of Crimea, where Russian-style repressive laws were enacted. Hundreds of journalists suddenly found themselves in new conditions without the tools to protect themselves and report from conflict areas — a glaring problem.

But, as the war began, foreign journalists came to Ukraine, looking for local producers and fixers to help them report the story. Many people — film producers, art managers, political scientists — have stepped up to help them, but they have practically no journalism or conflict reporting experience either. And many don’t have an understanding of how to calculate risks.

The number of injured and killed reporters is constantly rising. Working as a journalist in the field is very dangerous, even with a helmet and bulletproof vest. My colleagues and I have been woken up in the middle of the night by air raid sirens and have rushed to a bomb shelter to take cover. I’ve spent hours at a time sitting in the shelter because a bomb could fly into your house at any moment. Reporting on the street doesn’t feel safe, not only because of the danger from the sky but also because somebody could misinterpret your actions, as people are very suspicious of others these days. And, if you’re in Russian-occupied territory, it means that you can’t work as a journalist at all.

But it’s not just about the incredible destructiveness and unpredictability of the war in Ukraine: Russia is also targeting journalists for elimination as part of their so-called “special military operation.”

Perhaps the most eloquent picture that describes the essence of this war unleashed by Putin is the footage of a pregnant woman being rushed out of a bombed-out maternity hospital in Mariupol, which was mercilessly destroyed by Russian troops. Those images were taken by my colleagues and friends, AP journalists Zhenya Maloletka and Mstyslav Chernov. Russian state TV channels called them “propagandists” and alleged that the pictures were staged. Because of that reporting, Russian troops were hunting Maloletka and Chernov, who were under constant threat. With the help of the Ukrainian military, they miraculously managed to get out of the city surrounded by Russian troops.

The Putin regime doesn’t want eye witnesses. His propaganda machine constantly lies, reporting that the Ukrainians are shelling their cities and civilians themselves. The Russian regime is trying to destroy the very value of freedom, and who, if not the press, can bear witness to his atrocities? For every lie, journalists find thousands of facts to disprove them every day. The work of reporters, editors, producers, photographers, and videographers in Ukraine has a very high price. Some have already paid with their lives. We use all our strength to keep reporting so that the world can see Russia’s invasion for what it is — an attempt to take our freedom from us. They may try, but they won't succeed.

Katerina Sergatskova, editor-in-chief of Zaborona Media and co-founder of the 2402 Foundation, which helps journalists in Ukraine. She has reported from the occupied territories in Ukraine and Iraq. She is an author of “Goodbye, ISIS: What Remains Is Future. Stories of the terrorists from the Eastern Europe.”