In the opening panel of the “Aftermath” conference, “Life After Death: War, Memory and American Identity,” historian, author and Harvard University President Drew Gilpin Faust and psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton, known for his pioneering studies of Hiroshima survivors and Nazi doctors, discussed war, trauma and death and the role that journalists play in developing narratives to chronicle and share these experiences. The moderator was Jacki Lyden, a host and correspondent for National Public Radio, who since 1990 has reported from more than a dozen conflict zones in the Middle East and Afghanistan. An edited version of their conversation follows:

Lyden: In your long years of studying psychohistory in Vietnam and Nazism and cults, have you thought about the ways that storytellers tell stories and if we are human enough in our storytelling?

Lifton: I’ve thought a lot about stories in relationship to extreme trauma; and I’ve thought a lot about survivors and the psychology of the survivor. One model that’s useful because it’s so simple and general—and many people in this room have been using it or something like it—is to look at the psychology of the survivor.

In every chapter of Drew Faust’s book, “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War,” I thought about Vietnam, Hiroshima and the Holocaust. The connecting link is the psychology of the survivor. There is the indelible image of that death encounter; it includes a struggle with feeling—how much I can feel or not feel. It includes usually a kind of self-condemnation for remaining alive while others died and not doing more to stop the evil force. But above all the survivor’s preoccupation is with meaning. How can I understand this vastly death-saturated event? And if I can’t understand it I can’t understand or deal with the rest of my life. That is the connecting point.

Journalists are really mediators between those immediate survivors who experience the war or the event viscerally and the more distant survivors—the rest of us on the home front. The journalists, by telling the survivors’ stories, are a witness to the witness and they bring that story to the larger society. So the psychology of the survivor is key.

Faust: What is the future of these countries that have recently lost the dead? How will the dead and the trauma have an effect in years to come? One aspect that I think is probably generalizable beyond the war I know best, which is the Civil War, is that the dead turn into The Dead, with capital letters. After a time, they are no longer mourned so much as individual lost brothers, fathers, sons, wives, children, but they instead take on a meaning as a kind of political force, a shared loss that then can become a justification for more wars or national conflicts, or something of that sort. That’s one of the things that happens: that the mourning becomes generalized and takes on a nationalist or shared or political meaning beyond the individual emotional trauma of loss.

Lifton: That’s a crucial point. That, again, comes down to the meaning we give to the dead. In the dead lodge all moral authority and people assert moral authority by speaking on behalf of the dead. Read the “Iliad” and there are voices in Homer—even though the “Iliad” is the glorification of the warrior hero in many ways—often women’s voices that say this war may not have been worth the suffering it has caused. Perhaps these deaths cannot be justified. That is the alternative meaning from the traditional warrior ethos given to those deaths that “we must not let the dead have died in vain,” and, therefore, we extend the war. The alternative meaning is to question. It’s often a meaning through the meaninglessness of war. It’s a survivor mission that embarks on a determined cause of questioning and opposition to the war; and that’s the meaning that is taken from the dead. We should not lose sight of that meaning nor suppress it in our work as journalists or as scholars.

Another point is that no tragedy, no disaster, no matter how great, has an inherent meaning. We create meaning from it. We are meaning-hungry creatures and we must create meaning every moment of our lives, but all the more so with the kinds of tragedies that absolutely destroy and disrupt lives. That means that every generation has its own set of meanings. The flow of history is a series of survivals and of meaning structures that we create and recreate. There’s no end to it and there’s no single meaning that ever dominates.

RELATED ARTICLE

Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, uses “Billy Budd” to talk about the concept of “inside narrative.” It is important for us to be brought closer to the actuality of war. There is nothing more valuable and more beautiful than the interview method whether for the journalist or the scholar, especially when dealing with contemporary war. It cuts through the platitudes and the ideological assertions and gets to the direct human experience and especially the human pain. Once you talk to somebody who’s fighting a war and who tells you what it’s really like, you’re into that inner-narrative we heard about in terms of Herman Melville’s “Billy Budd,” rather than an outside narrative. You’re getting to the real human cost of war and the real suffering.

Related to this can be a macho assumption on the part of the journalist as well as the fighter; “Well, I’m a tough-minded journalist. I don’t get excited about these things. I can plunge into it and take care of it.” Then one over-extends oneself psychologically instead of pacing oneself as one must, as an athlete does, in order to deal with these enormously demanding issues. The writing and work of journalist Chris Hedges is very important in all this because he wrote in his 2002 book, “War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning” about the deep attraction of war for many journalists. War can attract because it’s a form of transcendence. With killing or dying you transcend the banality of ordinary existence. That can have enormous appeal. But all that has to be observed self-critically and its appeal recognized and contested.

Faust: Robert E. Lee, watching the slaughter at Fredericksburg, said, “It is good that war is so horrible, or we might grow to like it.”

Earlier, Jacki, you observed that there are so many people whose stories aren’t in print or who aren’t able to tell their stories and we’re not paying attention to all these stories. One of the things that strikes me is that trauma and silence often speak to me together. So how do you tell stories when people are silent or unable to express what a trauma means? I’ve seen often in the Civil War that soldiers would write home and say, “Words cannot express …,” “There is no language that can grasp …,” “I could not possibly tell you what happened today.” The need to acknowledge the inability to speak and the necessity of silence it seems to me has to be overcome to deal with trauma the way you journalists want to.

An allied correspondent stands before the shell of a movie theater in Hiroshima in September 1945, a month after the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the city to hasten Japan’s surrender. Photo by Stanley Troutman/The Associated Press.

Lifton: The deeply traumatized person is caught between wishing to talk about nothing but his or her trauma and being unable to talk about it. Therefore, one can be completely stilled. That requires a process of opening out, of two human beings in dialogue who are exchanging ideas both being in some way vulnerable. Some people have to stay silent for a long period of time, then eventually—and this happens with many Holocaust survivors—years later, perhaps decades later, they can begin to speak. It should be emphasized that it is impossible to describe the most extreme kind of experience. Words are not adequate to it. Sometimes images do a little better.

As journalists and scholars we can translate the words that people begin to tell us into images. When I heard descriptions of what happened in Hiroshima, I had never seen or experienced anything like it. I found myself trying to create pictures in my mind of the words people were telling me so that I could take in and get closer to what they were describing. It’s a constant effort to be able to take in this extreme trauma and to be able to connect with people who go through it. We need to have a little humility in recognizing that they know things that we don’t know. Gradually that unmentionable or unknowable kind of experience takes on some kind of form, even though imperfect and scattered and skewed. Then, we play a role by recreating it in our own narrative that gives it more form. We do best when we reach deeply into the pain from which to make that narrative.

Journalists: Opening Out

Lyden: Something I think has been done well in human rights reporting is when someone can go back and find out what that victim was doing two years later, three years later, five years later. Some of this only comes with time. That would change the nature of trauma reporting not just in war zones but in school killings and other violent events. We need a dimensionality of time other than get it on by five o’clock tonight and make it four minutes long.

Lifton: Journalists have a crucial role because they’re at the traumatized environment more quickly than scholars or philosophers. In that way, they mediate. They bring the narrative to us. There’s no getting away from that role of the journalist being there, being the early responders, and having this crucial function of making this narrative, and the narratives determine how we go about things.

The war on terror was the given official narrative as a survivor mission from 9/11. This survivor mission became the narrative of a war on terror, which was to eliminate evil in the world. Think how important the building of that narrative is and how important the role is of journalists in either acquiescing to that narrative or, better, contesting it.

Drew Faust brings out in her book how in the middle of the 19th century the idea of a good death was very strong. People were to die in a good way; one tried to arrange that good death. We’ve pretty much lost that in the 21st century but also because of the wars. I can’t help but remember the story told me by one veteran about dying in Vietnam. It’s the very antithesis of anything we might call a good death. He told how he was in a helicopter flying as a passenger, and in that same helicopter was an enormous portable toilet. He said, “What I thought is the way to die would be for this plane to crash and then I’d die in the middle of shit; and that’s the only way to die in Vietnam.” It was the very extreme of a good death, but it says something about what that war meant or was falsified and didn’t mean to the people fighting in it.

Psychic numbing is a diminished capacity or inclination to feel. It’s much easier to involve oneself or to become numbed where people are different and especially if they’re considered the enemy. Psychic numbing is something that can afflict any of us and all of us.

There’s always an imperfect balance between how much feeling one cuts off and how much one remains vulnerable. As a recorder of these events, journalist or scholar, one has to still remain vulnerable and not numb oneself in an exaggerated way. Psychic numbing, a degree of it, occurs to the victim; it occurs in the perpetrator from a distance in another way; and it also occurs in the would-be narrator of that experience.

The narrator opens things out by entering into it and then telling the story to the larger population. In entering into it, since you’re not a victim of that particular disaster, you do have greater freedom and less numbing to contend with so you take advantage of that position in forming our narrative. Everything that happens from then on should be in the direction of that opening out: the journalist entering in and telling his or her story; performers in writing and creating art in relation to extreme trauma; scholars immersing into that death-haunted realm; and all of us. All of that is a process of opening out. I think one humanizes the larger society in the very process of doing it.

It’s extremely demanding to get close to extreme pain. Society will use every mechanism to distance itself or distance its people from that pain. Different societies in different times of history will do it in different ways. Yet it’s always there. I think that has to be recognized as a kind of limitation of the human condition. Our task, as people who address these issues, is to get a little closer and to form narratives that enable people to connect.

Extreme trauma transcends cultural differences. I’ve worked with American trauma of an extreme kind, with trauma in Japan with Hiroshima, and in Germany and Europe with the Holocaust. There’s a commonality of pain and of the whole survivor experience, even though you must immerse yourself in these cultures to get at it: you must be sensitive to the cultural nuances in order to understand what’s happened to people in that culture. But when you do there’s that final common pathway of extreme suffering and of survivor struggles.

The degree to which war reverberates from the individual to the family to the whole social system and how its messages always break down, we often are distanced from this because it’s happening to the other rather than to our own troops, which are tightly knit and retain their structure and their institutional integrity. The breakdown of the alleged enemy and what’s happening in the other culture on a mass level is something that we should tell about in our stories about Iraq.

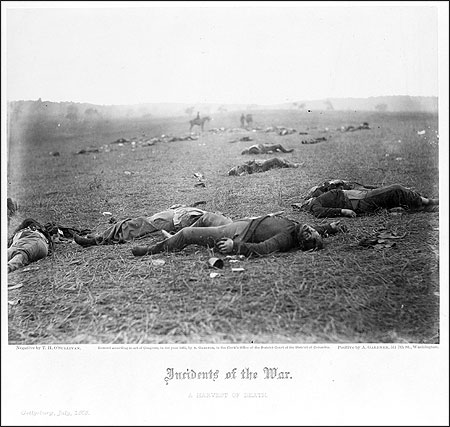

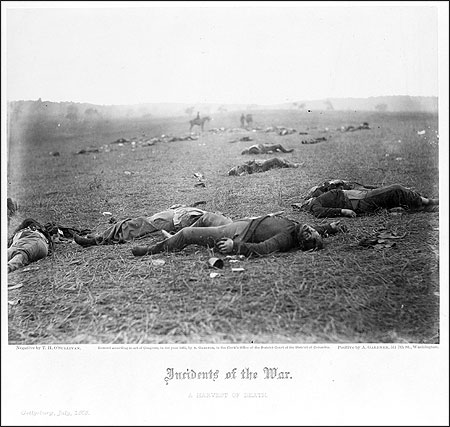

The soldiers who gave their lives in the Civil War, above at the Battle at Gettysburg, gradually became The Dead, a singular political force and shared loss, according to historian Drew Gilpin Faust. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Making Real: Death and War

Faust: One of my book’s chapters is called “Realizing.” I used that as a chapter title because I was so struck, as I was reading letters and diaries, by the use of a word that was very familiar to me—realize—in a way that was quite unlike any use of that word that I think we’re accustomed to in our time. It was used in the context of war in a very literal way: realizing, to make real. Individuals would talk about how they couldn’t realize a death: They couldn’t realize their brother or their husband had been killed. They couldn’t realize that this person was gone. What they meant was make that death a reality in my life. Make me understand that my life has been changed because some person that was so important to it is now absent from it.

For me there was a kind of materiality about this notion of making it real and it involved bodies. If you saw a body, you were much more able to realize because you had a real piece of evidence of that loss. So this suggested all kinds of aspects of trauma and loss. How do you come to grips with what is real about it, what is tangible, what is transforming, what is enduring? How does it go from your head to your actuality and how does it go from the actuality to your head, and how do those things interact?

Lifton: That very word anticipates a lot of psychoanalytic thought. There is even a prominent defense mechanism of de-realization—the process of preventing, resisting making it real—which is what many people you wrote about suffered from and wanted to overcome; and there are other defense mechanisms, like repression or isolation or denial, all of which represent a form of what I am calling psychic numbing. There’s usefulness in recognizing that all of these things are related to feeling or not feeling. You need to feel that death and that loss to make it real so that you can go on with your life.

There is another thing I would like to say about this issue of numbers. I think it was Arthur Koestler who said this: “Statistics don’t bleed.” That’s true. If you say a hundred thousand or a million it doesn’t register; but the way in what was almost the last chapter of your book, “Accounting,” depicted numbers, the overwhelming numbers and then the building of numbers gave me a new understanding of what it meant for all those numbers of deaths to be recorded in Vietnam and, more recently, the very small numbers of deaths in Iraq as they were broadcast one at a time. They had a powerful impact on each of us, especially when you question that war with each number building. So statistics can bleed when we take the time and the energy to enter into what they really are, what they constitute.

Audience members had an opportunity to ask questions of the speakers.

Question: Can you tell us a little bit about comparisons between the death rituals from the Civil War and what you’re seeing from Iraq today?

Faust: One very dramatic difference is the visibility of the Civil War dead, the numbers of funerals, the Lincoln death processions, Stonewall Jackson—very public, weeklong death rites, and the invisibility of the Iraq dead. Today the Pentagon announced that at last the coffins of the military dead from Iraq and Afghanistan can be photographed. It’s a big contrast, not simply that the numbers of Civil War dead were so great—that there were just funerals all the time—but also the willingness and, in fact, the eagerness to make these deaths visible. I think it’s a very important contrast.

Lifton: There’s also the element of the technological distancing from death. Somebody in Vietnam did a very informal survey that’s very illuminating. He talked to helicopter pilots, to the pilots of medium bombers, and to the pilots of high-level bombers in terms of their emotions. The helicopter pilots had all the emotions of ground troops: all the conflicts and pain. The pilots of medium bombers just saw little figures on the ground and didn’t really feel too much, but felt a little. And the pilots of the high-altitude bombers saw nothing, were totally on instruments, and it really took an act of moral imagination for them to even think about what happened on the ground. That’s an example of technological distancing in warfare and, of course, even more so for civilian populations.

Question: President Faust, the chapter that comes after “Dying” is called “Killing” and it’s about what it was like for Civil War soldiers to kill another human being. Do either of you have thoughts on that side of the trauma issue?

Lifton: The Vietnam veterans I spoke with were very concerned about killing as well as dying. It was either killing or the death of a buddy—witnessing dying—that began their journey from war supporters or at least obedient warriors into being opponents of the war. It was that death encounter.

On the one hand, it’s difficult to kill enemies. One military psychiatrist did a study in which he found that most soldiers in most wars didn’t fire their guns. You had to really train them to distance themselves from the target and not see it as human in order for them to kill that person. When you get hand-to-hand warfare as sometimes happened in Vietnam those barriers are no longer there and you really suffer the pain. Anybody I came upon who killed somebody in Vietnam had all kinds of emotions and difficulties about it.

There is something else that has to be questioned. It’s often said that it doesn’t matter whether or not you support a war or what the war’s purposes are, you’re just there in a combat unit and that’s all that matters. That isn’t true. In World War II—and to some extent in the Civil War as Drew Faust described it—when people really believed in their mission they could feel terrible about killing somebody, but then come out and think, “This is a dreadful thing, even an atrocity, but it had to happen and, in the end, it was for a good purpose. We did defeat evil.” With Vietnam and Iraq that last part is missing: it was a terrible thing, it was an atrocity, and I can find no justification for it. That’s where the killing of another person becomes extremely traumatizing and a source of self-condemnation and guilt.

Lyden: In your long years of studying psychohistory in Vietnam and Nazism and cults, have you thought about the ways that storytellers tell stories and if we are human enough in our storytelling?

Lifton: I’ve thought a lot about stories in relationship to extreme trauma; and I’ve thought a lot about survivors and the psychology of the survivor. One model that’s useful because it’s so simple and general—and many people in this room have been using it or something like it—is to look at the psychology of the survivor.

In every chapter of Drew Faust’s book, “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War,” I thought about Vietnam, Hiroshima and the Holocaust. The connecting link is the psychology of the survivor. There is the indelible image of that death encounter; it includes a struggle with feeling—how much I can feel or not feel. It includes usually a kind of self-condemnation for remaining alive while others died and not doing more to stop the evil force. But above all the survivor’s preoccupation is with meaning. How can I understand this vastly death-saturated event? And if I can’t understand it I can’t understand or deal with the rest of my life. That is the connecting point.

Journalists are really mediators between those immediate survivors who experience the war or the event viscerally and the more distant survivors—the rest of us on the home front. The journalists, by telling the survivors’ stories, are a witness to the witness and they bring that story to the larger society. So the psychology of the survivor is key.

Faust: What is the future of these countries that have recently lost the dead? How will the dead and the trauma have an effect in years to come? One aspect that I think is probably generalizable beyond the war I know best, which is the Civil War, is that the dead turn into The Dead, with capital letters. After a time, they are no longer mourned so much as individual lost brothers, fathers, sons, wives, children, but they instead take on a meaning as a kind of political force, a shared loss that then can become a justification for more wars or national conflicts, or something of that sort. That’s one of the things that happens: that the mourning becomes generalized and takes on a nationalist or shared or political meaning beyond the individual emotional trauma of loss.

Lifton: That’s a crucial point. That, again, comes down to the meaning we give to the dead. In the dead lodge all moral authority and people assert moral authority by speaking on behalf of the dead. Read the “Iliad” and there are voices in Homer—even though the “Iliad” is the glorification of the warrior hero in many ways—often women’s voices that say this war may not have been worth the suffering it has caused. Perhaps these deaths cannot be justified. That is the alternative meaning from the traditional warrior ethos given to those deaths that “we must not let the dead have died in vain,” and, therefore, we extend the war. The alternative meaning is to question. It’s often a meaning through the meaninglessness of war. It’s a survivor mission that embarks on a determined cause of questioning and opposition to the war; and that’s the meaning that is taken from the dead. We should not lose sight of that meaning nor suppress it in our work as journalists or as scholars.

Another point is that no tragedy, no disaster, no matter how great, has an inherent meaning. We create meaning from it. We are meaning-hungry creatures and we must create meaning every moment of our lives, but all the more so with the kinds of tragedies that absolutely destroy and disrupt lives. That means that every generation has its own set of meanings. The flow of history is a series of survivals and of meaning structures that we create and recreate. There’s no end to it and there’s no single meaning that ever dominates.

RELATED ARTICLE

Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, uses “Billy Budd” to talk about the concept of “inside narrative.” It is important for us to be brought closer to the actuality of war. There is nothing more valuable and more beautiful than the interview method whether for the journalist or the scholar, especially when dealing with contemporary war. It cuts through the platitudes and the ideological assertions and gets to the direct human experience and especially the human pain. Once you talk to somebody who’s fighting a war and who tells you what it’s really like, you’re into that inner-narrative we heard about in terms of Herman Melville’s “Billy Budd,” rather than an outside narrative. You’re getting to the real human cost of war and the real suffering.

Related to this can be a macho assumption on the part of the journalist as well as the fighter; “Well, I’m a tough-minded journalist. I don’t get excited about these things. I can plunge into it and take care of it.” Then one over-extends oneself psychologically instead of pacing oneself as one must, as an athlete does, in order to deal with these enormously demanding issues. The writing and work of journalist Chris Hedges is very important in all this because he wrote in his 2002 book, “War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning” about the deep attraction of war for many journalists. War can attract because it’s a form of transcendence. With killing or dying you transcend the banality of ordinary existence. That can have enormous appeal. But all that has to be observed self-critically and its appeal recognized and contested.

Faust: Robert E. Lee, watching the slaughter at Fredericksburg, said, “It is good that war is so horrible, or we might grow to like it.”

Earlier, Jacki, you observed that there are so many people whose stories aren’t in print or who aren’t able to tell their stories and we’re not paying attention to all these stories. One of the things that strikes me is that trauma and silence often speak to me together. So how do you tell stories when people are silent or unable to express what a trauma means? I’ve seen often in the Civil War that soldiers would write home and say, “Words cannot express …,” “There is no language that can grasp …,” “I could not possibly tell you what happened today.” The need to acknowledge the inability to speak and the necessity of silence it seems to me has to be overcome to deal with trauma the way you journalists want to.

An allied correspondent stands before the shell of a movie theater in Hiroshima in September 1945, a month after the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the city to hasten Japan’s surrender. Photo by Stanley Troutman/The Associated Press.

Lifton: The deeply traumatized person is caught between wishing to talk about nothing but his or her trauma and being unable to talk about it. Therefore, one can be completely stilled. That requires a process of opening out, of two human beings in dialogue who are exchanging ideas both being in some way vulnerable. Some people have to stay silent for a long period of time, then eventually—and this happens with many Holocaust survivors—years later, perhaps decades later, they can begin to speak. It should be emphasized that it is impossible to describe the most extreme kind of experience. Words are not adequate to it. Sometimes images do a little better.

As journalists and scholars we can translate the words that people begin to tell us into images. When I heard descriptions of what happened in Hiroshima, I had never seen or experienced anything like it. I found myself trying to create pictures in my mind of the words people were telling me so that I could take in and get closer to what they were describing. It’s a constant effort to be able to take in this extreme trauma and to be able to connect with people who go through it. We need to have a little humility in recognizing that they know things that we don’t know. Gradually that unmentionable or unknowable kind of experience takes on some kind of form, even though imperfect and scattered and skewed. Then, we play a role by recreating it in our own narrative that gives it more form. We do best when we reach deeply into the pain from which to make that narrative.

Journalists: Opening Out

Lyden: Something I think has been done well in human rights reporting is when someone can go back and find out what that victim was doing two years later, three years later, five years later. Some of this only comes with time. That would change the nature of trauma reporting not just in war zones but in school killings and other violent events. We need a dimensionality of time other than get it on by five o’clock tonight and make it four minutes long.

Lifton: Journalists have a crucial role because they’re at the traumatized environment more quickly than scholars or philosophers. In that way, they mediate. They bring the narrative to us. There’s no getting away from that role of the journalist being there, being the early responders, and having this crucial function of making this narrative, and the narratives determine how we go about things.

The war on terror was the given official narrative as a survivor mission from 9/11. This survivor mission became the narrative of a war on terror, which was to eliminate evil in the world. Think how important the building of that narrative is and how important the role is of journalists in either acquiescing to that narrative or, better, contesting it.

Drew Faust brings out in her book how in the middle of the 19th century the idea of a good death was very strong. People were to die in a good way; one tried to arrange that good death. We’ve pretty much lost that in the 21st century but also because of the wars. I can’t help but remember the story told me by one veteran about dying in Vietnam. It’s the very antithesis of anything we might call a good death. He told how he was in a helicopter flying as a passenger, and in that same helicopter was an enormous portable toilet. He said, “What I thought is the way to die would be for this plane to crash and then I’d die in the middle of shit; and that’s the only way to die in Vietnam.” It was the very extreme of a good death, but it says something about what that war meant or was falsified and didn’t mean to the people fighting in it.

Psychic numbing is a diminished capacity or inclination to feel. It’s much easier to involve oneself or to become numbed where people are different and especially if they’re considered the enemy. Psychic numbing is something that can afflict any of us and all of us.

There’s always an imperfect balance between how much feeling one cuts off and how much one remains vulnerable. As a recorder of these events, journalist or scholar, one has to still remain vulnerable and not numb oneself in an exaggerated way. Psychic numbing, a degree of it, occurs to the victim; it occurs in the perpetrator from a distance in another way; and it also occurs in the would-be narrator of that experience.

The narrator opens things out by entering into it and then telling the story to the larger population. In entering into it, since you’re not a victim of that particular disaster, you do have greater freedom and less numbing to contend with so you take advantage of that position in forming our narrative. Everything that happens from then on should be in the direction of that opening out: the journalist entering in and telling his or her story; performers in writing and creating art in relation to extreme trauma; scholars immersing into that death-haunted realm; and all of us. All of that is a process of opening out. I think one humanizes the larger society in the very process of doing it.

It’s extremely demanding to get close to extreme pain. Society will use every mechanism to distance itself or distance its people from that pain. Different societies in different times of history will do it in different ways. Yet it’s always there. I think that has to be recognized as a kind of limitation of the human condition. Our task, as people who address these issues, is to get a little closer and to form narratives that enable people to connect.

Extreme trauma transcends cultural differences. I’ve worked with American trauma of an extreme kind, with trauma in Japan with Hiroshima, and in Germany and Europe with the Holocaust. There’s a commonality of pain and of the whole survivor experience, even though you must immerse yourself in these cultures to get at it: you must be sensitive to the cultural nuances in order to understand what’s happened to people in that culture. But when you do there’s that final common pathway of extreme suffering and of survivor struggles.

The degree to which war reverberates from the individual to the family to the whole social system and how its messages always break down, we often are distanced from this because it’s happening to the other rather than to our own troops, which are tightly knit and retain their structure and their institutional integrity. The breakdown of the alleged enemy and what’s happening in the other culture on a mass level is something that we should tell about in our stories about Iraq.

The soldiers who gave their lives in the Civil War, above at the Battle at Gettysburg, gradually became The Dead, a singular political force and shared loss, according to historian Drew Gilpin Faust. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Making Real: Death and War

Faust: One of my book’s chapters is called “Realizing.” I used that as a chapter title because I was so struck, as I was reading letters and diaries, by the use of a word that was very familiar to me—realize—in a way that was quite unlike any use of that word that I think we’re accustomed to in our time. It was used in the context of war in a very literal way: realizing, to make real. Individuals would talk about how they couldn’t realize a death: They couldn’t realize their brother or their husband had been killed. They couldn’t realize that this person was gone. What they meant was make that death a reality in my life. Make me understand that my life has been changed because some person that was so important to it is now absent from it.

For me there was a kind of materiality about this notion of making it real and it involved bodies. If you saw a body, you were much more able to realize because you had a real piece of evidence of that loss. So this suggested all kinds of aspects of trauma and loss. How do you come to grips with what is real about it, what is tangible, what is transforming, what is enduring? How does it go from your head to your actuality and how does it go from the actuality to your head, and how do those things interact?

Lifton: That very word anticipates a lot of psychoanalytic thought. There is even a prominent defense mechanism of de-realization—the process of preventing, resisting making it real—which is what many people you wrote about suffered from and wanted to overcome; and there are other defense mechanisms, like repression or isolation or denial, all of which represent a form of what I am calling psychic numbing. There’s usefulness in recognizing that all of these things are related to feeling or not feeling. You need to feel that death and that loss to make it real so that you can go on with your life.

There is another thing I would like to say about this issue of numbers. I think it was Arthur Koestler who said this: “Statistics don’t bleed.” That’s true. If you say a hundred thousand or a million it doesn’t register; but the way in what was almost the last chapter of your book, “Accounting,” depicted numbers, the overwhelming numbers and then the building of numbers gave me a new understanding of what it meant for all those numbers of deaths to be recorded in Vietnam and, more recently, the very small numbers of deaths in Iraq as they were broadcast one at a time. They had a powerful impact on each of us, especially when you question that war with each number building. So statistics can bleed when we take the time and the energy to enter into what they really are, what they constitute.

Audience members had an opportunity to ask questions of the speakers.

Question: Can you tell us a little bit about comparisons between the death rituals from the Civil War and what you’re seeing from Iraq today?

Faust: One very dramatic difference is the visibility of the Civil War dead, the numbers of funerals, the Lincoln death processions, Stonewall Jackson—very public, weeklong death rites, and the invisibility of the Iraq dead. Today the Pentagon announced that at last the coffins of the military dead from Iraq and Afghanistan can be photographed. It’s a big contrast, not simply that the numbers of Civil War dead were so great—that there were just funerals all the time—but also the willingness and, in fact, the eagerness to make these deaths visible. I think it’s a very important contrast.

Lifton: There’s also the element of the technological distancing from death. Somebody in Vietnam did a very informal survey that’s very illuminating. He talked to helicopter pilots, to the pilots of medium bombers, and to the pilots of high-level bombers in terms of their emotions. The helicopter pilots had all the emotions of ground troops: all the conflicts and pain. The pilots of medium bombers just saw little figures on the ground and didn’t really feel too much, but felt a little. And the pilots of the high-altitude bombers saw nothing, were totally on instruments, and it really took an act of moral imagination for them to even think about what happened on the ground. That’s an example of technological distancing in warfare and, of course, even more so for civilian populations.

Question: President Faust, the chapter that comes after “Dying” is called “Killing” and it’s about what it was like for Civil War soldiers to kill another human being. Do either of you have thoughts on that side of the trauma issue?

Lifton: The Vietnam veterans I spoke with were very concerned about killing as well as dying. It was either killing or the death of a buddy—witnessing dying—that began their journey from war supporters or at least obedient warriors into being opponents of the war. It was that death encounter.

On the one hand, it’s difficult to kill enemies. One military psychiatrist did a study in which he found that most soldiers in most wars didn’t fire their guns. You had to really train them to distance themselves from the target and not see it as human in order for them to kill that person. When you get hand-to-hand warfare as sometimes happened in Vietnam those barriers are no longer there and you really suffer the pain. Anybody I came upon who killed somebody in Vietnam had all kinds of emotions and difficulties about it.

There is something else that has to be questioned. It’s often said that it doesn’t matter whether or not you support a war or what the war’s purposes are, you’re just there in a combat unit and that’s all that matters. That isn’t true. In World War II—and to some extent in the Civil War as Drew Faust described it—when people really believed in their mission they could feel terrible about killing somebody, but then come out and think, “This is a dreadful thing, even an atrocity, but it had to happen and, in the end, it was for a good purpose. We did defeat evil.” With Vietnam and Iraq that last part is missing: it was a terrible thing, it was an atrocity, and I can find no justification for it. That’s where the killing of another person becomes extremely traumatizing and a source of self-condemnation and guilt.