“These are not the questions of a journalist,” the wary young man with piercing eyes advised as we sat in the sheik’s house along the lush ribbon of green that brackets the Euphrates, verdant even in the punishing mid-summer heat. “These are the queries of an intelligence agent!”

Such an accusation was nothing to be shrugged off in Iraq’s Sunni Arab heartland, home base of the violent insurgency that was just then gathering momentum. The “I gotcha” look in the eyes of the young man didn’t inspire confidence in a place where mistrust of outsiders was endemic. My interpreter and colleague, Suhail Ahmad, informed me that it was an auspicious time to change the conversation. I put my notebook away nonchalantly, being careful to show no sign of panic to the young man and the equally suspicious companions who had gathered to scope us out. We dropped the topic that had brought us here, a discussion of a religious student from the area who had risen to be imam of a mosque in nearby Fallujah; he had been killed when an explosion ripped through the mosque compound. The U.S. Army said a bomb factory on the mosque grounds had ignited by mistake, killing the young imam and a number of his acolytes. The men at the sheik’s house called them martyrs, killed by the Americans, and weren’t tolerant of alternate narratives.

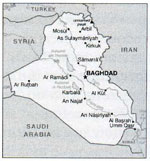

Instead, we proceeded to speak at length about the many complexities of Sufi philosophy and its ascetic teachings, which are a major influence in the conservative Sunni hamlets here. We broke bread and partook of the sheik’s okra stew, a sure sign that tensions had eased. Soon the young man with the hostile mien was wondering if I was interested in converting. After another two hours, and after endless glasses of sweet tea and communal goblets of ice water, it seemed finally safe to take our leave. We demurred the young man’s offer that we visit him in his home for a soft drink. Our driver made sure that no one followed us on the lonely roads out, through the date-palm groves, now bursting with multihued fruit, past the turquoise-domed minarets of nearby Fallujah and on to Baghdad.

Reporting: Violence Changes the Way It’s Done

That’s the way it used to work in Iraq, back in the summer of 2003. Foreign journalists felt relative safety in traveling most anywhere, though one always had to be cautious. But generally the Iraqi people were willing to speak, even in the ancient towns along the Euphrates where the insurgency was burgeoning. Our local staffs functioned pretty much like interpreters and fixers in any other foreign news bureau. But lamentably, in Iraq the safety curve always seems to be on the decline. The sense of being under siege only grew; we took more precautions. Night trips were avoided; we began to send scout cars to check out dicey sites before visiting. Everything began to come asunder in March 2004 with the notorious murder of four U.S. contractors in Fallujah and the subsequent Marine attack on the city of mosques, as it is known.

Before long, Fallujah, a place many of us had frequented—I used to make a point of having lunch in Haji Hussein’s, the famous kebaberie on the main drag—became a no-go zone. Then came the steady stream of kidnappings, beheadings, the emergence of insurgent checkpoints where abduction was a likely fate. Most of us in the foreign press corps in Baghdad moved into guarded compounds or walled-off existing residences and hired security guards. Nowadays, many of us travel with two cars, an armed bodyguard in the rear vehicle.

Given these circumstances, our interpreters became something much more than translators. They were transformed into journalists—surrogate journalists. Rather than exposing Western staffers to a bombing aftermath, where tension often reigns, we now typically send an Iraqi translator/reporter. They conduct street interviews. They arrange meetings and also scout potential interview sites to be sure if the rendezvous points are safe. The danger of taking a non-Iraqi along is two-way: Not only are foreigners threatened, but Iraqis working with us are also at risk.

It is a strange and off-putting way to work, one none of us has ever gotten used to. One colleague referred to it as journalism by “remote control.” And so it is at times. It is also very conflicting: Western staffers remain behind while our Iraqi colleagues go out in the streets and gather the raw information for our stories, risking their lives at every corner. The whole enterprise smacks of some kind of journalistic caste system, and it frustrates correspondents who, by nature, like to get out on the streets. But in my experience, there is great mutual respect between Western and Iraqi staffers. Most every Western news agency in Baghdad has adapted this method of working, to one degree or another.

Reporters try to push the envelope: We visit enclosed and relatively secure settings like homes, political party headquarters, offices and clubs. Mosques, especially Sunni mosques, are more problematic. Traveling through the capital, with its epic traffic jams, regular car bombs, ambushes and permanent aura of latent threat, is always a bit tense. Lately a relative calm in Shiite areas has reopened Shiite neighborhoods like Sadr City to non-Iraqi reporters, though one must always tread carefully. Westerners can work with some caution in the Shiite south, but they have to fly to Basra or Najaf: Driving the principal roads south, routes we traversed without a second thought a little more than a year ago, now means passing through a kidnapper’s gauntlet.

Dangerous Assignments for Iraqi Translators

For Iraqi translators-turned-reporters, training has been largely an on-the-job affair. None of the half-dozen or so translators working for the Los Angeles Times had previous journalistic experience until the U.S. invasion. Few Iraqis did, in a country lacking a free press for decades. Good Iraqi translators are not easy to find. Arabic speakers from other Arab countries stand out—Iraqi Arabic is very distinct—and also have difficulty working in the culturally and politically charged atmosphere prevalent in Iraq. The translator ranks at the Los Angeles Times have included a doctor, a pharmacist, a university student, an architect, a former professional government translator, and an ex-employee of the information ministry. All have tremendous language skills, intelligence and heart: I credit several with extracting me (and other staffers) from extremely volatile predicaments—possibly saving our lives. None lack for bravery and dedication. After so much time together, we share a bond like infantrymen who have fought a war together. We celebrate their weddings and the births of their children; they send regards to our families on the other side of the world. Sadly, visiting their homes now presents a danger for them. Few tell their friends or neighbors what they do for a living. Working for “the Americans” can be a capital crime here.

For the Iraqi staffs, straight translating of interviews, Arabic-language media reports, documents and other items is easy enough. All are proficient in English. Learning to bring back quotes and descriptions from news scenes is learned quickly as well. The real challenges are developing journalistic intuition, learning to use initiative to follow a story, asking the right questions, capturing the telling details, and identifying issues that attract Western readers. These are very difficult skills to teach; they are instincts that we’ve all developed through the years.

The tradeoffs are many. Recently, one of our Iraqi translators/correspondents volunteered to go to a very dangerous town southeast of Baghdad where dozens of bodies had been washing ashore along the Tigris. We had held off on the trip for a few days until it was relatively safe. He returned without a problem; his files had excellent, and new, information. He interviewed the police chief, medical officials, relatives of the dead, and other crucial players in what remained a murky story of sectarian slaughter. But we needed more texture. And when I spoke with him upon his return, he recounted a moving anecdote: As he was waiting at the police station, a pickup truck arrived with the latest body scooped from the river. Police with plastic gloves and rags tied across their noses and mouths inspected and photographed the badly decomposed remains and looked for identifying jewelry or personal items; they then sent the corpse to the cemetery to be interred according to Muslim tradition. It was compelling material that helped put the story on Page One. It wasn’t in the initial file, but he had the material.

We try to hold weekly meetings for the staff and emphasize the need to think ahead and creatively about issues in the news in Iraq. The newspaper sent two of our translators, including Suhail Ahmad, for a week–long training session in Jordan that was sponsored by the Knight Foundation. Our colleagues and friends are getting better all the time, and all are proud to see their names in the newspaper, either as contributors or as bylined authors. We work as a team. Their loyalty is humbling.

As bureau chief, I stress the need for newly arrived Western reporters to spend time in the translators’ room, discussing possible stories, chatting about what people are saying in this broken nation. Often our Iraqi employees— translators, drivers, guards—are our most visceral link to the outside world of ordinary Iraqis. It’s not an ideal working situation. Nothing in Iraq is especially ideal right now. We all wish it were different. Yet that’s being a journalist in Baghdad these days. Our staffs have learned from us. But more than anything else, we have learned from them. And we are forever grateful.

Patrick J. McDonnell, a 2000 Nieman Fellow, is the Los Angeles Times bureau chief in Baghdad. He is scheduled to transfer to Buenos Aires later this summer.

Such an accusation was nothing to be shrugged off in Iraq’s Sunni Arab heartland, home base of the violent insurgency that was just then gathering momentum. The “I gotcha” look in the eyes of the young man didn’t inspire confidence in a place where mistrust of outsiders was endemic. My interpreter and colleague, Suhail Ahmad, informed me that it was an auspicious time to change the conversation. I put my notebook away nonchalantly, being careful to show no sign of panic to the young man and the equally suspicious companions who had gathered to scope us out. We dropped the topic that had brought us here, a discussion of a religious student from the area who had risen to be imam of a mosque in nearby Fallujah; he had been killed when an explosion ripped through the mosque compound. The U.S. Army said a bomb factory on the mosque grounds had ignited by mistake, killing the young imam and a number of his acolytes. The men at the sheik’s house called them martyrs, killed by the Americans, and weren’t tolerant of alternate narratives.

Instead, we proceeded to speak at length about the many complexities of Sufi philosophy and its ascetic teachings, which are a major influence in the conservative Sunni hamlets here. We broke bread and partook of the sheik’s okra stew, a sure sign that tensions had eased. Soon the young man with the hostile mien was wondering if I was interested in converting. After another two hours, and after endless glasses of sweet tea and communal goblets of ice water, it seemed finally safe to take our leave. We demurred the young man’s offer that we visit him in his home for a soft drink. Our driver made sure that no one followed us on the lonely roads out, through the date-palm groves, now bursting with multihued fruit, past the turquoise-domed minarets of nearby Fallujah and on to Baghdad.

Reporting: Violence Changes the Way It’s Done

That’s the way it used to work in Iraq, back in the summer of 2003. Foreign journalists felt relative safety in traveling most anywhere, though one always had to be cautious. But generally the Iraqi people were willing to speak, even in the ancient towns along the Euphrates where the insurgency was burgeoning. Our local staffs functioned pretty much like interpreters and fixers in any other foreign news bureau. But lamentably, in Iraq the safety curve always seems to be on the decline. The sense of being under siege only grew; we took more precautions. Night trips were avoided; we began to send scout cars to check out dicey sites before visiting. Everything began to come asunder in March 2004 with the notorious murder of four U.S. contractors in Fallujah and the subsequent Marine attack on the city of mosques, as it is known.

Before long, Fallujah, a place many of us had frequented—I used to make a point of having lunch in Haji Hussein’s, the famous kebaberie on the main drag—became a no-go zone. Then came the steady stream of kidnappings, beheadings, the emergence of insurgent checkpoints where abduction was a likely fate. Most of us in the foreign press corps in Baghdad moved into guarded compounds or walled-off existing residences and hired security guards. Nowadays, many of us travel with two cars, an armed bodyguard in the rear vehicle.

Given these circumstances, our interpreters became something much more than translators. They were transformed into journalists—surrogate journalists. Rather than exposing Western staffers to a bombing aftermath, where tension often reigns, we now typically send an Iraqi translator/reporter. They conduct street interviews. They arrange meetings and also scout potential interview sites to be sure if the rendezvous points are safe. The danger of taking a non-Iraqi along is two-way: Not only are foreigners threatened, but Iraqis working with us are also at risk.

It is a strange and off-putting way to work, one none of us has ever gotten used to. One colleague referred to it as journalism by “remote control.” And so it is at times. It is also very conflicting: Western staffers remain behind while our Iraqi colleagues go out in the streets and gather the raw information for our stories, risking their lives at every corner. The whole enterprise smacks of some kind of journalistic caste system, and it frustrates correspondents who, by nature, like to get out on the streets. But in my experience, there is great mutual respect between Western and Iraqi staffers. Most every Western news agency in Baghdad has adapted this method of working, to one degree or another.

Reporters try to push the envelope: We visit enclosed and relatively secure settings like homes, political party headquarters, offices and clubs. Mosques, especially Sunni mosques, are more problematic. Traveling through the capital, with its epic traffic jams, regular car bombs, ambushes and permanent aura of latent threat, is always a bit tense. Lately a relative calm in Shiite areas has reopened Shiite neighborhoods like Sadr City to non-Iraqi reporters, though one must always tread carefully. Westerners can work with some caution in the Shiite south, but they have to fly to Basra or Najaf: Driving the principal roads south, routes we traversed without a second thought a little more than a year ago, now means passing through a kidnapper’s gauntlet.

Dangerous Assignments for Iraqi Translators

For Iraqi translators-turned-reporters, training has been largely an on-the-job affair. None of the half-dozen or so translators working for the Los Angeles Times had previous journalistic experience until the U.S. invasion. Few Iraqis did, in a country lacking a free press for decades. Good Iraqi translators are not easy to find. Arabic speakers from other Arab countries stand out—Iraqi Arabic is very distinct—and also have difficulty working in the culturally and politically charged atmosphere prevalent in Iraq. The translator ranks at the Los Angeles Times have included a doctor, a pharmacist, a university student, an architect, a former professional government translator, and an ex-employee of the information ministry. All have tremendous language skills, intelligence and heart: I credit several with extracting me (and other staffers) from extremely volatile predicaments—possibly saving our lives. None lack for bravery and dedication. After so much time together, we share a bond like infantrymen who have fought a war together. We celebrate their weddings and the births of their children; they send regards to our families on the other side of the world. Sadly, visiting their homes now presents a danger for them. Few tell their friends or neighbors what they do for a living. Working for “the Americans” can be a capital crime here.

For the Iraqi staffs, straight translating of interviews, Arabic-language media reports, documents and other items is easy enough. All are proficient in English. Learning to bring back quotes and descriptions from news scenes is learned quickly as well. The real challenges are developing journalistic intuition, learning to use initiative to follow a story, asking the right questions, capturing the telling details, and identifying issues that attract Western readers. These are very difficult skills to teach; they are instincts that we’ve all developed through the years.

The tradeoffs are many. Recently, one of our Iraqi translators/correspondents volunteered to go to a very dangerous town southeast of Baghdad where dozens of bodies had been washing ashore along the Tigris. We had held off on the trip for a few days until it was relatively safe. He returned without a problem; his files had excellent, and new, information. He interviewed the police chief, medical officials, relatives of the dead, and other crucial players in what remained a murky story of sectarian slaughter. But we needed more texture. And when I spoke with him upon his return, he recounted a moving anecdote: As he was waiting at the police station, a pickup truck arrived with the latest body scooped from the river. Police with plastic gloves and rags tied across their noses and mouths inspected and photographed the badly decomposed remains and looked for identifying jewelry or personal items; they then sent the corpse to the cemetery to be interred according to Muslim tradition. It was compelling material that helped put the story on Page One. It wasn’t in the initial file, but he had the material.

We try to hold weekly meetings for the staff and emphasize the need to think ahead and creatively about issues in the news in Iraq. The newspaper sent two of our translators, including Suhail Ahmad, for a week–long training session in Jordan that was sponsored by the Knight Foundation. Our colleagues and friends are getting better all the time, and all are proud to see their names in the newspaper, either as contributors or as bylined authors. We work as a team. Their loyalty is humbling.

As bureau chief, I stress the need for newly arrived Western reporters to spend time in the translators’ room, discussing possible stories, chatting about what people are saying in this broken nation. Often our Iraqi employees— translators, drivers, guards—are our most visceral link to the outside world of ordinary Iraqis. It’s not an ideal working situation. Nothing in Iraq is especially ideal right now. We all wish it were different. Yet that’s being a journalist in Baghdad these days. Our staffs have learned from us. But more than anything else, we have learned from them. And we are forever grateful.

Patrick J. McDonnell, a 2000 Nieman Fellow, is the Los Angeles Times bureau chief in Baghdad. He is scheduled to transfer to Buenos Aires later this summer.