A young boy named Charlie pauses on his tricycle beside his backyard pool, mouth agape in a wail as his father grabs his half-naked mother. Two-year-old Memphis sobs as she sees a fight between her mother and her mother’s boyfriend erupt into violence in their kitchen.

Though the two moments were witnessed and photographed 30 years apart by different photographers—Donna Ferrato and Sara Naomi Lewkowicz, respectively—the scenes of domestic violence are nearly identical in content and emotional resonance. Both images are single, stunning snapshots in photo essays that graphically depict the complex intimacies of relationships fraught with violence.

Ferrato’s and Lewkowicz’s photos speak to the photographers’ individual commitment to documenting difficult but compelling moments, as well as to the ability of photojournalism to evoke the kind of public awareness that gets policy written. Yet, we are also forced to sit with the discomfort of whether anyone has the right to witness and publish such private moments of violence. What does it mean to circulate such photographs of children caught up in their parents’ violent feuds? Charlie (full names of survivors are not disclosed to protect their anonymity)—whose father was infamously photographed hitting his mother in the ’80s—would be well into adulthood now.

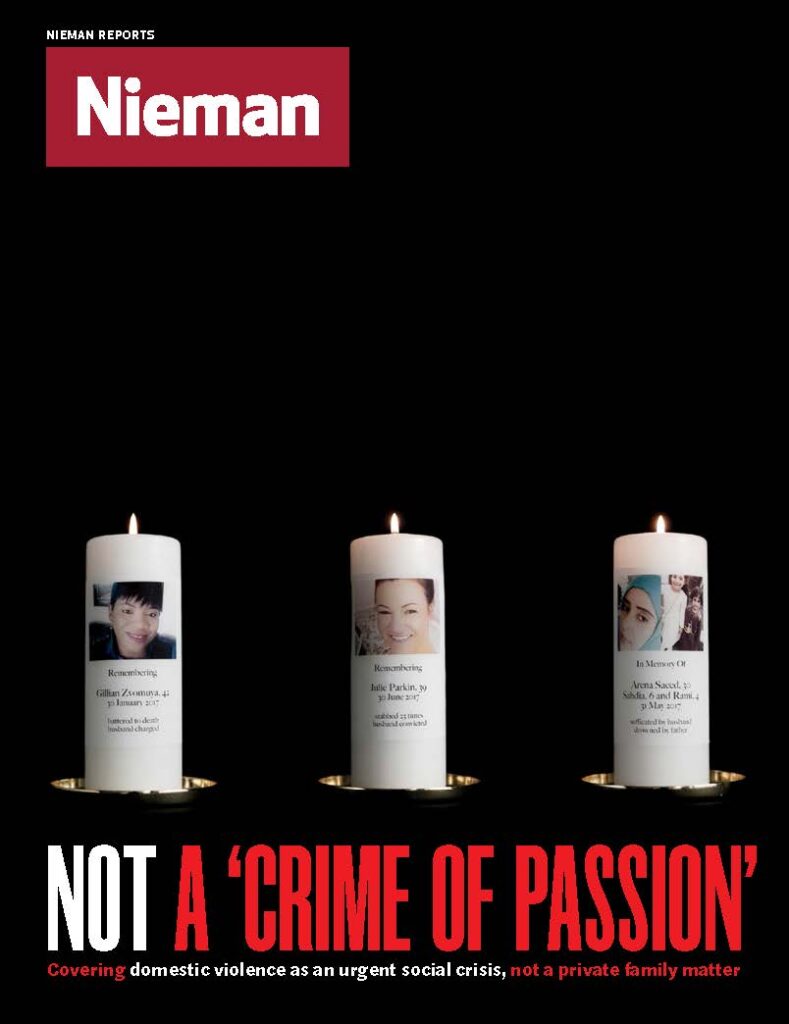

As much as these stories should be told in order to effect change, journalists are also beholden to the people in the stories we tell. Where is the line between respecting the needs of trauma survivors or the deceased and the public’s need to know?

There is some hope that informing audiences about important issues and appreciating the boundaries of those who have experienced trauma are not always at odds. Rich Glickstein, a photojournalist turned clinical social worker, has deeply considered this intersection, due to his experience working closely with people recovering from trauma. He sees a benefit to traumatized people sharing their stories with journalists and, by extension, the viewing public. It “allows them to engage their grief and start to rebuild trust in taking back the narrative that someone essentially wrote for them when being battered or assaulted,” says Glickstein.

What does it mean to circulate such photographs of children caught up in their parents’ violent feuds?

However, the way reporters address and relay narratives around domestic violence impacts audience interpretation as well as those whose stories are being told. The framing through which we see violence deeply affects whether the result of that viewing is empathy—which evinces understanding and a recognition of shared humanity—or merely sympathy, which is less tied to action. One frame through which we often view domestic violence is the police photograph: images of women visualized entirely as victims, their skin raked from fresh scratches, purple bruises blossoming across eyes, cheeks, and extremities.

Mugshot-esque ruminations on abuse leave out so much necessary context. Looking directly into the camera—whether defiantly or imploringly—the portrait subject is made to stand in for both a decontextualized version of him- or herself and to represent a compendium of enacted violence on so many others experiencing similar trauma.

An insistence upon capturing visual evidence of abuse under the stylized eye of crime photos underscores the necessity of seeing the violence enacted on women in the moment or after the fact for it to be believed.

Yet photography, including those police images that define abuse as merely represented by the evidence of physical trauma, misses an opportunity to educate us about traumas otherwise not so easily visualized. Mental illness, socioeconomic status, and the failures of the state to protect abused individuals or rehabilitate their assailants are only a few of the issues at work in the cycle of domestic violence abuse. Glickstein also points to journalism’s difficulty representing the extreme complexity of domestic violence, saying“that’s one of the things we unfortunately miss, because we try to distill it and make it digestible.”

Wisconsin photographer Lauren Justice took an alternative approach when she turned her camera on domestic abusers in a batterers intervention class. While the men acknowledge responsibility for their violence to varying degrees in Justice’s account of their conversations, her moody portraits of violent offenders portray an array of competing emotions. The audience is left to contend with what these men have done and might yet still do, just as they appear to be struggling with themselves. Taken in conjunction with images of those who have suffered abuse, this nuanced approach eschews the simplistic narratives to which domestic violence coverage often falls prey. Instead Justice’s project exemplifies good journalism: seeking out many angles to provide deeper knowledge.

Kelli Moore, an assistant professor of media, culture, and communication at NYU who is writing a book on the media history of photographic evidence of domestic violence, says domestic violence “photojournalism operates best through an ethos of development—of people and ideas that challenge us to think critically about how to repair the effects of the cycle of violence.” Longform documentary projects offer just such an opportunity for a more critical engagement with the underlying issues of domestic abuse.

In Lewkowicz’s photo essay of a young mother’s volatile relationship with her boyfriend, Shane, the intimate view makes plain the surrounding issues that often inform an abused woman’s options. It’s important to delve into the cyclical nature and uneven power structures of domestic violence to bring attention to both the severity and ubiquity of the problem, as well as how it can be difficult for women to leave such relationships due to lack of financial resources or alternate housing. Without acknowledging the undercurrents of ever-present control and psychological manipulations in a home that has become a war zone, we can’t hope to address this social crisis.

In addition to educating the public about this problem, interactions between a photojournalist and trauma survivor can be productive when great care is taken to build a relationship on honesty. One of the most important things a photojournalist can do when covering a subject like domestic violence is be truthful up front that the story might be packaged and disseminated in ways that are often beyond even the control of the photographer.

Glickstein suggests explaining that it is the work of journalism to turn intricate issues into stories that are both succinct and compelling to the public. “Tell them I’m going to do the best I can in telling this story, and that might entail there being some difficult images to look at,” says Glickstein. “Prepare for that, prepare to have a camera pointed at you when you may be at your most vulnerable.”

“From a psychological perspective, from the subject’s side they’re giving trust and then realizing that the person they’re giving trust to is worthy of it, recognizing that can be restorative,” says Glickstein. “They’ve confided, they’ve put their truth out there and were able to say, ‘This is what happened to me as I remember it.’ That can be a cathartic experience.”

It’s evident from the intimacy depicted in Lewkowicz’s photos of Maggie, the mother in her photo essay, that an incredible level of trust was established early on. Both Lewkowicz and Maggie exhibit bravery by collaborating to tell Maggie’s story. The photojournalist chose to remain in a dangerous space, making it possible for others to later know that story. She didn’t simply determine it was a private matter and leave a family to suffer alone in a potentially deadly situation—what so many others in positions of authority have done. Rather, she stayed true to the edict to witness and show audiences uncomfortable truths.

Maggie’s courage in sharing those difficult moments with someone else was an implicit recognition that people need to know not just that this happens but how it happens. Thus, the photo essay and accompanying text vividly narrate the evolution of a loving relationship prior to violence, the couple in the moment of a physical attack, and the aftermath of violence as a mother and her children struggle to find a way forward.

Interactions between a photojournalist and trauma survivor can be productive when great care is taken to build a relationship on honesty

Because Lewkowicz continued photographing Maggie and her family for years after the initial attack, she was able to document what recovering from abuse entails and how the choice to leave a violent partner can have long-lasting effects. Moore says “when photojournalists and survivors create images together,picture taking can become a real moment of learning and reflection for both.” This kind of insight and access is made possible by a dedication to open collaboration and a commitment to telling an ongoing, unfolding story that is emblematic of so many other domestic violence stories.

Ferrato’s collaborative and continuous approach to documenting a family fractured by violence offers a similar intervention in the history of popular photojournalistic treatments of domestic violence. She, too, went on to photograph Elisabeth (the mother of Charlie, mentioned earlier) in the aftermath of the attack captured on camera as she and her five children left their abusive home, attempting to start anew. Both Ferrato and Lewkowicz share an understanding that telling an honest and complete story about domestic violence doesn’t end with depicting an attack. That’s only the beginning of trying to depict a problem as insidious and pervasive as domestic abuse.

Additionally, each photographer attempted to intervene in the violence as they strove to tell the story unfolding in front of them. Lewkowicz made certain 911 had been called before continuing to photograph the attack, and Ferrato has said she raised her camera because she believed that photographing the violence would stop the attacker.

As an audience to the documentation of such familial violence, we are not allowed to callously blame these survivors for their own trauma, nor can we pretend we don’t know it is a substantive problem. Good journalism makes us aware of a problem we didn’t realize existed, helps us understand an issue more clearly, and galvanizes us to act. The photos of Lewkowicz, Ferrato, and Justice do precisely that.