Libraries and news organizations are increasingly collaborating to better serve their communities, with librarians teaming up with journalists to promote media literacy and tackle misinformation, develop community journalists, spur civic engagement, and take on reporting projects. Some of them are sharing physical spaces, with newsrooms—temporary or permanent—popping up amidst (or at least not far from) library shelves to enable even greater engagement between reporters and librarians—and the citizens they both seek to serve. A look at three news organizations that have found homes inside libraries:

WGBH Studio at the Boston Public Library

When the historic Boston Public Library was undergoing renovations in 2015, it sought a vendor to occupy a corner of the new space, an open area with huge glass windows facing a busy downtown thoroughfare. Instead of selecting one of the usual suspects—like a coffee shop or retail—the library settled on a different kind of tenant: a public radio station. NPR member station WGBH now operates a 1,000-square-foot TV and radio facility right inside the library, with no walls restricting library-goers from wandering into the main studio (and the aptly-named adjacent eatery, the Newsfeed Café) and watching twice-weekly live tapings of the local program “Boston Public Radio” as well as broadcasts of other feature programs, interviews, and musical performances.

This unusual arrangement has proved to be a boon for both the library and WGBH. The studio provides a space for collaboration between the two institutions—for example, WGBH has teamed up with the business library to put on a financial workshop, and children’s programming events have been hosted inside the studio—as well as a chance to attract new audiences. It “really adds another reason for people to come to the library. It raises the profile of the library in the community as a whole,” says David Leonard, president of the Boston Public Library. “You will frequently, with some of the special guests they have in when they're broadcasting live, have standing room only.”

Meanwhile, WGBH gets an opportunity to show library-goers how public radio works, up close and personal, and expose them to notable guests—everyone from James Comey to Kristine Lilly to Celtic musicians—they might not normally have access to. More essential is that the library satellite studio, in a sharp contrast to WGBH’s main studio on the outskirts of Boston, allows the outlet to more directly interact with Bostonians and engage with them in their programming, through segments like “Hear at the Library,” where library patrons are invited to weigh in on a wide-range of topics, from the most memorable Red Sox moments to gripes with Boston’s public transportation. Most importantly, perhaps, the shared space is helping change the notion of what a public library—and a news outlet—can be in 2019: the Boston Public Library, says WGBH’s BPL studio director Linda Polach, had a mission to “take libraries into the next realm, into the 22nd century, by making them more accessible and inviting and interesting and stimulating. We're part of that … We bring something vibrant and exciting and different into a library.”

The Sprawl’s Pop-Up Newsroom at Calgary Public Library

In Canada, the crowdfunded, Calgary-based online news organization The Sprawl—which, in the style of slow journalism, focuses in-depth on a single topic at a time—provided a model of how newsrooms and libraries can share space in a more ephemeral manner. Like its journalism projects, The Sprawl’s newsroom at the Calgary Public Library was a pop-up, located inside the new central library for the first few months of 2019. The library was looking for a way to activate an open area called the Create Space, while Sprawl founder and editor Jeremy Klaszus was looking for a way to get out of the office and engage with citizens. “People often come to the library to find out more about where they live [and] that's exactly what we're trying to do, too, with The Sprawl. We want to tell the stories of this city. We want to tell them in an in‑depth way. Those things totally jive,” says Klaszus.

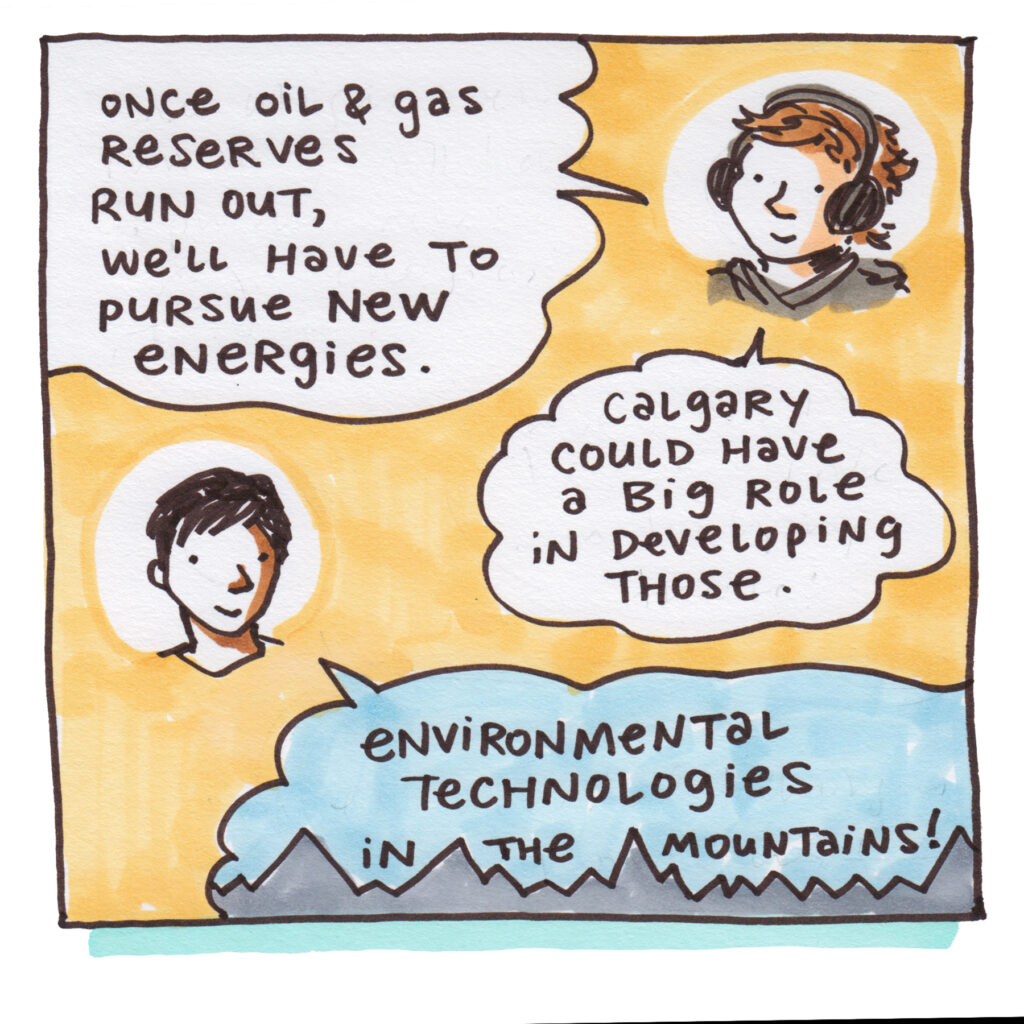

Rather than a place for Klaszus and Sprawl contributors to take up residence to do work, the newsroom was more of a mini-exhibit for library-goers, both to get familiar with the history of Calgary and its news outlets and to provide input for the news outlet’s project at the time, which was centered around the topic of “what’s next” for Calgary and what the city will look like—politically, socially, culturally—25 years from now, in 2044. In a space that was both informative and playful, visitors could use a typewriter to jot down their thoughts on what they want the Calgary of the future to look like, while also taking a look at a curated collection of old articles on the topic. “One of the cool things we did for the newsroom was worked with the local history librarian to dig through a bunch of archival material and look at, ‘OK, Calgary has wrestled with this question many, many times in the past. What direction should the city go? What's next?’” says Klaszus. “When you come to the newsroom, you can read about how, in the 1970s, Calgary was trying to figure out a planning blueprint for its growth, or 15 years ago Calgary was talking about, ‘How do we transition away from being a one‑industry town?’ You get a portrait of some successes, but also some failures.”

Klaszus and freelancers working on the Calgary 2044 edition would frequently spend time at the pop-up newsroom, to interact with locals and answer questions about journalism and Calgary; The Sprawl also hosted a live edition of their podcast inside the library’s theater. One of the main benefits of engaging with people—students, especially—in the pop-up newsroom, for Klazmus? The idea that exposing them to a newsroom, even if a temporary one, might increase their interest and trust in news organizations. “How do you take that newsroom idea, break it open, invite people into it, and let them explore the inner workings of it? That's been fun with the students because they ask, ‘How do these decisions get made?’ They have all kinds of questions about the news, how it's changing. There's for sure a news literacy element to it.”

NOWCastSA at the San Antonio Public Library

Nonprofit news organization NOWCastSA is located on the sixth floor of a bold, colorful building designed by renowned Mexican architect Ricardo Legorreta in San Antonio, a building that also just so happens to be the city’s central library. NOWCastSA—described as a sort of local C-SPAN by executive director Charlotte-Anne Lucas—livestreams local events and news and has two offices housing their studio and staff (largely made up of college interns) inside the San Antonio Public Library, which covers the online news outlet’s rent in exchange for coverage of certain library programs and events and additional video services. “One of the joys is that we are not a department of the city,” unlike the library, says Lucas. “We’re an independent 501(c)(3) that happens to live [at the library], and has a great partnership.”

Besides covering some of the institution’s programming, NOWCastSA has teamed up with the library for events, such as working with the teen services department to put on storytelling classes and a Mini Maker Faire last fall. The library and NOWCastSA also work together to put on media literacy workshops that Lucas calls “Crap Detection 101.” Library director Ramiro Salazar has called the unique partnership between the two entities “a perfect fit” and Lucas—who happens to be the daughter of a librarian—agrees: “For us, it’s a joy-and-a-half.”