The first tactic the people hoarding money, power, and secrets will try is to befriend you. You join their side; they join yours. Everyone benefits. Perhaps you gain a new advertiser and the unpleasant story your newspaper has been poking around is conveniently forgotten.

If you resist efforts to co-opt you, then a series of downward steps begin, a hierarchy of persuasion. Bribes are offered in amounts that can dwarf a journalist’s salary in the developing world.

If that fails, too, the threats start, with the promised consequences ramping up and up. Violence is the last thing anyone actually wants, so before that final step, those in power will pressure your advertisers, your distributors, and your bank to starve you into submission.

“They’ll only kill you if the denial of revenue does not bring you down,” says Dele Olojede, who for two years published a groundbreaking newspaper based in Lagos, Nigeria. “Luckily for me, I guess, cutting off revenue did bring us down. I’m still alive.”

From 2009 to 2011 Olojede published Next, the sleek Mario García-designed, social-media savvy, muckraking newspaper the Pulitzer Prize-winning Olojede had dreamed up while working for Newsday. The paper’s mission was to relentlessly investigate and bring to light corruption in Olojede’s homeland, and it had worked only too well. There was rot, Olojede says, in the nation’s bloodstream, and the paper uncovered it everywhere. The exhilaration for a time obscured the fact that the threads of Next’s downfall were woven into its brash, idealistic founding.

“In a way, we were doomed from the start, but the extent to which we were doomed wasn’t clear to us,” Olojede says. “We were basically going after the people, or their associates, on whose advertising we depended, which was a contradiction in our mission.”

The traditional tension between media organizations’ editorial and business sides that investigative projects tend to stir up isn’t remotely unique to Africa, as anyone who’s covered news in a small town knows. But in terms of consequences, there’s a difference between angering the biggest car dealer in town and angering your country’s de facto president for life.

Journalism in Africa is an undeniably risky business

Journalism in Africa is an undeniably risky business, and harassment, beatings, and even murder are all in the arsenal of those who resent scrutiny. Since 2014, at least 29 journalists have been killed and scores imprisoned for their work in countries throughout Africa, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

It’s more typical to try to simply bog down bothersome reporters and publications. This neutralization is often easily accomplished in post-colonial nations where civil society is commonly stunted by despotism, poverty, and warfare, and private sectors squirm under the thumb of oligarchs. “It happens here and in other countries in Africa, says Joel Konopo, an investigative journalist from Botswana. “You are forced to choose between having a profitable newspaper or having a serious newspaper with no money.”

It’s worth noting that Africa—a vast continent of 1.2 billion people, tremendous linguistic and cultural diversity, and nearly 60 countries with governments that range from democratic, like South Africa’s, to brutally dictatorial, as in Eritrea—resists sweeping generalizations. But while local realities differ, African print newsgatherers are subject to the same litany of forces shaking up journalism worldwide: falling circulation, shriveling advertising revenue, confusion over how to monetize Internet traffic, and a focus on cheaper, faster, more vacuous clickbait content.

“It’s very difficult to support long-form investigative journalism in the same publications and on the same publishing schedules as the digital popcorn journalism,” says Chris Roper, former editor in chief of South Africa’s Mail & Guardian who now helps manage the nonprofit foundations African Network of Centers for Investigative Reporting (ANCIR) and Code for Africa, which supports data journalism on the continent.

The combined pressures have progressively reduced the scope for the time-consuming, expensive, and often nerve-wracking reporting that truly matters. “The stresses put on investigative units and the business models of newspapers are immense and growing,” Roper says. “For reasons of not compromising your business model or not compromising yourself ethically, investigative journalism will increasingly become removed from the business model.”

The new models on the rise in some ways mirror what’s taken place in the United States and elsewhere with nonprofit newsrooms like ProPublica and the Center for Public Integrity. But in Africa, they’re popping up with a frequency that bespeaks an added urgency, focusing on everything from government corruption to mapping-based environmental data journalism. Traditional newspapers are partnering with foundations like ANCIR for expertise and financial help, and journalists working solo or in small groups are creating their own web-based distribution platforms to insulate themselves from the nexus of business and politics.

From illegal cronyism and nepotism to human rights abuses, offshore accounts, and environmental destruction, incisive investigative work is being done throughout the continent. With tenacity and innovation that sometimes belies their lack of resources, journalists are uncovering the stories that the powerful want to keep buried.

DIRTY OIL, NIGERIA

Next’s triumphant last gasp began in April 2011, with a story it would have been hard to imagine in any other Nigerian newspaper at the time. Following its example, more outlets today, some of them staffed with journalists who started their careers at Next, take a hard look at the activities of business and political elites. At the time, the relentless investigative focus was “a shock to the system,” Olojede says. The six-part series on corruption in the country’s vast oil sector implicated top officials in “a magic wave of a pen [that] effectively transferred hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars—possibly billions—in public assets to private individuals without a public tender.”

The problem, in the eyes of the authorities, wasn’t damning assertions, but that Next was printing and posting online the documentation for its reporting about back-channel payments, bribes from major international companies, and the theft of public money. Government and oil company representatives angrily denied the paper’s allegations, arguing among other things that Next had started with a “jaundiced view” of an industry they said was benefiting the country as a whole. But Next kept publishing. “We had the document trail; we had recordings, audio and video,” says Musikilu Mojeed, the paper’s former investigations editor and current editor in chief of Premium Times, an online newspaper based in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city. “We went undercover and pretended to form a sham company. We met with agents of an office of the oil and gas ministry and were offering them bribes, and they accepted. The evidence we had was overwhelming.”

The investigators called themselves “Nexters.” Many weren’t journalists at all when they were hired in 2008 from a pool of 13,000 applicants, publisher Olojede says. “We decided not to rely on newsrooms in the country because by then they had been so damaged by corruption.”

The editors—a group with broad international journalism experience—put the hires through a six-month boot camp financed with some of the millions of dollars in loans Olojede had secured. They drilled the new hires on the basics of reporting and writing, and hammered them with the ethics of independent journalism—no bribes, favoritism, or misconduct allowed. It was modeled partly on what Olojede had soaked up in j-school at Columbia University and later at Newsday, where his series on the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide won the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. “We trained the hell out of them and made them proud to be there,” he says.

Next had attracted public attention and made powerful enemies before, but the oil ministry series was different. The public was transfixed, hanging on each new revelation, and the authorities were looking for someone to punish. As the paper went to press, managing editor Kadaria Ahmed was detained for questioning and investigative editor Mojeed and the rest of the investigative team hid out in a hotel to avoid the police.

The high-flying Next was already struggling with unexpectedly low revenue, and now a final exodus of advertisers began. In September 2011, the printing presses stopped. Then, in a bittersweet development, the paper began winning accolades for the coverage, including Mojeed’s Editor’s Courage Award from the Forum for African Investigative Reporters (FAIR) that November. He points to recent arrests and charges against oil ministry officials as vindication of Next’s risky reporting. “Everyone is covering it now,” he says. “But then we were alone, and we really took a risk.”

In Africa, investigative journalism outfits are popping up with a frequency that bespeaks an added urgency

Nexters have brought their investigative zeal to new posts. At Mojeed’s current web publication, Premium Times, a reporter and the publisher were arrested in January for the paper’s investigation of the Nigerian Army.

Next’s fall proved two things to Olojede: Commercial newspapers, with their high fixed costs and reliance on advertisers, are fatally hamstrung all over Africa. And secondly, swashbuckling investigative journalism that calls powerful leaders to account is doable, and the public hungers for it. “I think the future is bright even as the traditional media dies on the continent.”

SHOOT TO KILL, BOTSWANA

The way the Botswana Defence Force told it, troops had intercepted two gun-toting men in July 2012 carrying tusks from a poached elephant as they prepared to escape in the dark across the river that separates Botswana and Namibia. When confronted, the men made moves as if to shoot it out and were gunned down. A pair of Namibian poachers had been stopped, safeguarding the nation’s precious natural heritage—not to mention the lucrative safari and big game hunting industries that top government officials have direct stakes in.

That’s where it might have ended, except that almost four years later, a pair of journalists at the INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, a nonprofit founded in 2015 in the capital, Gaborone, began pondering a British filmmaker’s interview with the country’s environmental minister, Tshekedi Khama. In it, the official, who is the younger brother of Botswana President Ian Khama, boasts that even if poachers tried to surrender, they’d be shot.

“This was something that was not spoken of in Botswana, although many of our citizens think the government does have a right to kill poachers,” says Ntibinyane Ntibinyane, a former editor at the Mmegi newspaper who founded the INK Centre with erstwhile Botswana Guardian editor Joel Konopo. “We wanted to find out, was the government following a policy of extrajudicial killing?”

They’d still be wondering if they worked at their old newspapers, Ntibinyane says. Surviving in business and investigating alleged human rights abuses by the country’s first family are mutually exclusive goals. “The problem with a country where the government is the biggest player in the economy is that the government is also the biggest advertiser by far through state-owned companies. That is how they can stop you.”

But with a multi-year donation from the Open Society Initiative of Southern Africa, as well as United States governmental funding through the U.S. Embassy in Gaborone, the INK Centre didn’t need to please advertisers or politicians. The two spent months working sources in the Botswana Defence Force to document incidents in which poachers had been killed, and then went into the field for several weeks to visit the killing sites and family members of Namibians who’d been shot.

Working with investigative reporter Tileni Mongudhi from The Namibian, a newspaper based in Windhoek, Namibia, Ntibinyane and Konopo uncovered “several apparent inconsistencies” with the government’s story of the 2012 killing. The guns the men were carrying, including a puny .22-caliber rifle, were too underpowered to hunt elephant; the tusks reportedly found with them were not freshly removed, and no elephant carcass was located; although the men supposedly acted threateningly, one had been shot in the back of the head. The victims’ families, meanwhile, claim they were simply fishermen.

Surviving in business and investigating alleged human rights abuses by the country’s first family are mutually exclusive goals

When it was over, the reporters had documented a number of killings that looked suspiciously like extrajudicial executions by the military, and found evidence that around 30 Namibians and 22 Zimbabweans had met that fate in recent years. The Botswana government said it has not been involved in any extrajudicial border killings and said all BDF actions were “within the constraints of the prevailing statutes.”

The donations that support INK are a sword that cuts two ways, freeing its journalists from business concerns and government manipulation but opening them to accusations of outside control, and even of being funded by the U.S. government to destabilize Botswana. The smear campaign by government supporters is one that few take seriously, Ntibinyane says. “We do stuff that challenges power and exposes corruption and betrayal of public trust. This has caused the government so much discomfort, hence, the tired propaganda that we are CIA spies.” To guard their independence, however, INK uses donations from governmental sources solely to fund educational programs for aspiring investigative journalists—not for the projects themselves—and refuses corporate funding, he says.

The INK Centre is beginning to lay the groundwork for investigations of reported poaching deaths on borders with other nations, Konopo says. If the funding model they’ve chosen has some minor drawbacks, there’s no other way the work can get done. “We exist in an environment that is planned to make investigative journalism fail and prevent the truth from emerging,” Konopo says. “We do what we can do, and it is always a struggle.”

DIGGING IN DUNG, SOUTH AFRICA

A president under investigation for suspicious ties to foreign business magnates, with the financial dealings of his children and family woven throughout the growing scandal.

That’s the skeletal outline of an explosive narrative on “state capture”—powerful business interests and corrupt officials colluding to take over institutions, line their pockets, and subvert democracy—that the nonprofit amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism in Johannesburg has followed keenly since its principals split off from the Mail & Guardian newspaper in 2010. The vast body of work centers on ties between South African president Jacob Zuma and the Guptas, an extended clan led by several Indian businessmen who immigrated to South Africa in the 1990s.

“We’ve focused on two privileged families… to show how a tiny elite is managing to corner an extraordinary set of business opportunities by doing very lucrative deals with the state,” says Stefaans Brümmer, a founding partner of amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism (The name is isiZulu for “dung beetle;” the center’s motto is “Digging dung. Fertilizing democracy.”)

Last June, the center was putting out stories at a furious pace based on thousands of leaked emails—they’ve dubbed the series #GuptaLeaks—that appear to show how the family, among other things, lavishly bankrolled the president’s children, worked to bring officials under their sway, and were casually racist toward African subordinates. A lawyer for the family has blasted the email release as a political move and says the family denies any wrongdoing or under-the-table payments to officials.

It’s far from the center’s first scoop on the family. In an investigation that concluded in December, it linked them to a mysterious company that seemingly had to be paid millions of dollars before telecom contracts could be signed with state transport company Transnet. “We went in search of this company called Homix, which as we dug became more and more obvious was a front for the Guptas that leveraged their influence,” says Sam Sole, the other founding partner at amaBhungane.

Like Brümmer, he is a veteran investigative reporter and editor who’d previously written for the Mail & Guardian and wanted to focus solely on investigative journalism, rather than being on call for daily stories.

Transnet denies wrongdoing, responding to the series that it was “confident in [our] processes.” Zuma, meanwhile, has steadfastly denied the acceptance of illegal payments and other corruption allegations and insisted in March before the South African parliament that the Guptas have no influence on his governing decisions.

The relentless string of corruption scandals prompted the ruling African National Congress to seek a no-confidence vote to recall the increasingly embattled Zuma; the motion was defeated by narrow margins in early August. Such politics aren’t the center’s immediate concern, Brümmer says. “We don’t measure our success by saying, ‘Oh well, we’ve claimed another scalp,’ because one almost never claims a scalp. Our success is in the fact that we have mapped out what state capture is really all about… In that way, we’ve had a lot of traction, and now it’s not just our story, but it’s society’s story.”

Formerly funded mainly by the Mail & Guardian newspaper, amaBhungane is turning increasingly to South African society itself for sustenance. Although the center now relies on a number of large donors like South Africa’s Millennium Trust and the Open Society Foundation for South Africa, over 10 percent of amaBhungane’s budget comes from crowdsourcing—small direct donations from readers who value their work. (The stories, meanwhile, are given away to select outlets.)

The total ought to be higher this year; the #GuptaLeaks investigations had money pouring in as of early June, as readers registered their approval of the center’s work by opening their pockets. “The public now counts as one of our bigger donors and, of course, if one can get that to over 50 percent then so much the better, because the bigger that is, you’re not only more independent but your perceived independence is boosted,” Brümmer says. “We are big on independence.”

HOLES IN THE MAP, SOUTH AFRICA

The problem had festered in plain sight for decades. From diamonds and gold to coal, mining has long been one of the pillars of South Africa’s economy, and the result is a landscape scarred by thousands upon thousands of abandoned, un-remediated mine sites, many of them leaching poison into the water and toxic dust into the air.

But until an innovative investigative journalism outfit took on the problem using new ways of storytelling, no one knew the extent of it, or the fact that the environmental degradation is grinding on unabated.

“At least 60 billion rand [$4.6 billion] has been put up by mining companies for rehabilitation, but we’ve shown it is not being spent, and in fact no large mines have been closed in South Africa since 2011,” says Fiona Macleod, founder of Oxpeckers Center for Investigative Environmental Journalism. Like the founders of the similarly evocatively-named amaBhungane, Macleod had been a reporter at the feisty Mail & Guardian in Johannesburg and wanted to be in charge of her own investigations while focusing on environmental data journalism.

“I realized the whole media landscape was changing, and we needed to incorporate new media in that mission, so we started off with a geojournalism platform in 2012, combining data and mapping as a means of telling stories in an accessible format,” she says. The idea behind geojournalism is to serve up huge quantities of environmental data to readers through maps to make it tangible and build traditional investigative stories from the mapped evidence.

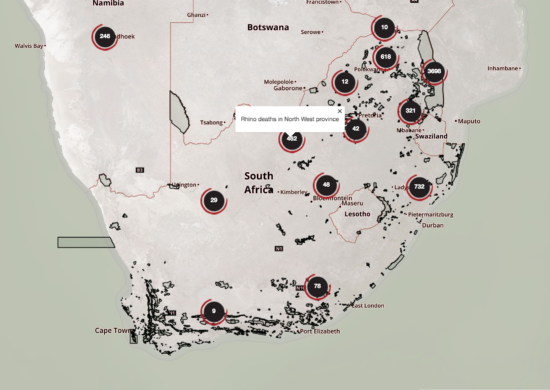

Macleod’s first big push was PoachTracker, which focuses on rhino poaching (oxpeckers are birds that have a symbiotic relationship with rhinoceros, eating parasitic bugs off their hides) and accompanies the interactive mapped data with investigative stories about how, where, and why, including a partnership with Asian journalists investigating the use of rhino horns in traditional Chinese medicine.

Oxpeckers’ new app, #MineAlert, developed with support from the Open Society Foundation for South Africa and Code for Africa, is even richer in data, with detailed information on many mines nationwide, along with functionality that allows trusted users to crowdsource more data.

Freelance journalist and Oxpeckers associate Mark Olalde compiled most of the data, making liberal use of South Africa’s relatively robust open records law, the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA). Olalde, a recent grad from Northwestern University’s Medill journalism school, was doing an internship at The Star, a Johannesburg newspaper, when he became fascinated by zama zama miners—small-timers who move into large abandoned mines to support themselves at great risk. Soon he was going from mine to mine gathering data and stories.

Not only were mining companies not bothering to close and clean up huge mines, he found, but the government had access to billions of dollars to begin cleanup that were going unused. South Africa’s Department of Mineral Resources didn’t respond to Olalde’s requests for an explanation of its practices for overseeing mine closures. Out of the hundreds of companies involved, many refused comment, while others attempted to shift blame to other companies or complained about unrealistic requirements of the law.

The 21-month investigation was shortlisted for a Global Editors Network Data Journalism Award, and Oxpeckers’ and Olalde’s data is being used by the South African parliament as it revises laws governing mine closure.

Much of his time was spent wrangling for information from South African provinces, Olalde says. “I set up something called PAIA day, and every Thursday I would spend a day calling every province in the country until I could get their data. It was nonstop pestering. They would answer the phone and say, ‘Oh, you again,’” Olalde says. “There was a sense that it’s kind of wasting our time to ask the government for anything—if we want to get anything from the government we have to get it in other ways. But sometimes you can get it if you ask enough.”

TRAIL OF WEALTH, ANGOLA

The reporting was both critical and balanced, but Rafael Marques de Morais was on his own. Instead of a pat on the back for hard-hitting coverage of national elections in 1992 intended to end a decades-long war in Angola, he learned the price of crossing the regime of Angolan president José Eduardo dos Santos. “I was sent to the military by my own newspaper,” he says. “However, the military found out it didn’t want me either.”

Returning to the capital, Luanda, he opted to buck the Angolan government’s active measures to limit independent voices “There’s always been a deep need for investigative journalism in this country,” he says. “It’s just me. I cannot set up an infrastructure, so I decided to focus on two subjects only: human rights and corruption.”

But first he had to find ways to gather information. Over the years, Marques de Morais learned to quietly cultivate the well-meaning and the disgruntled within the regime to gather information. He also discovered, in a country where open records laws are toothless, that public presidential decrees were a rich font of information about how Angola’s vast national resource wealth becomes personal wealth. “If you read the presidential decrees, in the big contracts, there is invariably someone from the regime or the presidential family involved, and it became my obligation to expose this,” he says. Dos Santos’ government has never admitted to any wrongdoing.

Commercial newspapers, with their high fixed costs and reliance on advertisers, are fatally hamstrung all over Africa

Marques de Morais has been called a political activist and a traitor, beaten up several times, and jailed for 40 days in 1999 after writing an article critical of the president. Though he was convicted, the sentence was suspended after the Open Society Justice Initiative (Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa, among other donors, helps Marques de Morais fund his ad-free investigations) and the International Centre for the Legal Protection of Human Rights argued his case before the United Nations Human Rights Committee.

His local knowledge drew Marques de Morais to the attention of Kerry Dolan, a journalist for Forbes magazine whose beat is the world’s wealthiest people. Tipped off that she needed to include glamorous presidential daughter Isabel dos Santos on Forbes’s list of Africa’s wealthiest, Dolan went looking for ways to quantify her wealth. “I initially reached out to him as a source, for what he knew about Isabel,” she says. “As I began talking to him, I realized, Oh no, he knew a lot and he had done a ton of reporting, and we should work on the story together.”

Paired up with an international publication with global reach, Marques de Morais was no longer alone on his mission. After a year of his on-the-ground reporting while Dolan worked international sources, the dual-byline story hit newsstands in August 2013. It revealed how Isabel dos Santos had piled up billions in assets from Angola’s diamond, oil, and telecom industries, among others—transferred by edict in a developing country with stratospheric levels of poverty, malnourishment, and infant mortality. A dos Santos representative told the pair that allegations of illegal wealth transfers between her and the government were “groundless and completely absurd.”

The article laid out what it called “a tragic kleptocratic narrative,” winning the 2014 Gerald Loeb International Award and sparking fury among the government and its supporters. “It was so well reported there was nothing they could do,” Marques de Morais notes. Still, the government found other ways to go after him, including prosecution for criminal defamation in conjunction with a 2011 book that documented hundreds of cases of murder and torture in conjunction with Angola’s diamond industry. Although convicted, his sentence was suspended in 2015, the same year he won the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Award.

Now, dos Santos representatives are taking a new tack. Recent emails to an international business reporter from a Portuguese PR firm representing dos Santos lobbed a now-familiar charge at his website, Maka Angola, denying wrongdoing on the first daughter’s part and accusing him of political attacks.

“Now they have started referring to me as ‘fake news,’” Marques de Morais says.