The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting supported the collaboration of a photographer and a poet who produced an Emmy Award-winning multimedia project about HIV in Jamaica. Photo by Joshua Cogan (www.joshuacogan.com).

The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting began with a simple idea—that we could leverage small travel grants to journalists to assure multiple voices on big global issues and at the same time help talented individuals sustain careers as foreign correspondents. Five years and some 150 projects later those remain key goals but our mission has expanded—and with it our sense of what is required of nonprofit journalism initiatives like the Pulitzer Center.

Some lessons we’ve learned:

Collaboration: Our best projects have entailed partnerships with multiple organizations and outlets. We developed our expertise on video by producing several dozen short pieces for the now defunct public television program “Foreign Exchange With Fareed Zakaria,” for example, and we extended our audience by partnering with YouTube on its first video reporting contest. In our project on Sudan we are collaborating with The Washington Post to support the work of journalist/attorney Rebecca Hamilton and funding complementary coverage on “PBS NewsHour.” We have worked in tandem with “NewsHour” and National Geographic to promote our common work on the global water crisis. In these and other reporting initiatives we have recruited donors with an interest in raising the visibility of systemic issues—and an appreciation that the journalism cannot succeed unless there is an assurance of absolute independence in our work.

RELATED ARTICLE

“Bearing Witness: The Poet as Journalist”

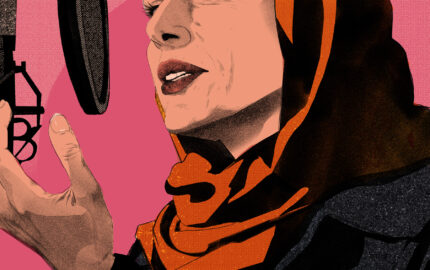

- Kwame DawesMultimedia and the Web: I began the Pulitzer Center with no video experience, thinking that our focus would be enterprise print projects of the sort I had done over three decades as a correspondent for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. I learned the power of video in the center’s first project, a trip I made with African Union peacekeeper forces in Darfur. At the suggestion of “Foreign Exchange,” I recruited Egyptian videographer Abdul Nasser Abdoun. The footage we collected led to a video report for “Foreign Exchange,” a televised panel of experts at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, and a longer documentary that we showed at three dozen universities—a far greater reach, in short, than the print report I wrote for the Post-Dispatch. Multimedia presentations have been a hallmark of Pulitzer projects ever since—from the photojournalism of Sean Gallagher in China and Fred de Sam Lazaro’s television reporting on food and water to immersive Web experiences such as “Hope: Living & Loving With HIV in Jamaica” that is built on the poetry of Kwame Dawes and won an Emmy last year for new approaches to news and documentaries. Livehopelove.com was an unconventional take on an important issue but it led to an abundance of conventional news-media coverage—from essays in The Washington Post and Virginia Quarterly Review to a featured interview on “NewsHour” and a one-hour radio documentary that aired on dozens of public radio stations. Projects like this have also given us rich visual assets to enhance the presentation of our work online, especially through the Gateway portals on our site that draw from our reporting around the world to address issues such as climate change, fragile states, and women and children in crisis.

Education and Outreach: The Gateways have also become a principal means of engaging middle school, high school, and college students. We began with the idea that our role was to fill gaps in the supply of high-quality journalism, with a focus on international reporting that traditional news outlets were increasingly less able to undertake on their own. We soon realized that to be effective we had to address the equal challenge on the demand side, especially among younger audiences with no attachment to traditional news media. We had to reach out to them where they are—in the classroom, on YouTube, and on Twitter, Facebook and other social media. The Pulitzer Center is now funded for 10 full time jobs; four of them are devoted almost exclusively to educational outreach and two others to social media and Web outreach. We produce dozens of journalist events at schools and colleges each year; we engage thousands of students through online encounters with journalists, with each other, and with individuals in the countries on which we report. On projects such as our reporting on water we have collected hundreds of “Share Your Stories” videos, short statements or reported pieces from interested individuals and students around the globe, all presented within the context of the high-end journalism we have sponsored. The idea is public engagement—informed engagement—with the issues that affect us all.

EDITOR'S NOTE

On April 30, Sawyer delivered a speech at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communications’ conference titled “New Journalism, New Ethics?”, in which he spoke in depth about the Uganda project.Editorial Standards: In the beginning we assumed that our role would focus on identifying stories worth covering and selecting journalists to do the work; we would provide funding and help with placement but the principal editorial supervision would come from the news media outlets with which the work was placed. We did not anticipate that most big regional newspapers would jettison their foreign editors and that national outlets would increasingly consider freelance pieces for publication or broadcast only when those pieces were nearly completed. That has placed a larger burden on organizations like the Pulitzer Center to provide editorial direction from within; so has the increasing prominence on our site of Untold Stories, which publishes blog posts from journalists in the field. A painful, useful learning experience for us was our photojournalism project on child sacrifice in Uganda, in which we briefly published and then withdrew images that we determined were inappropriate. The experience led us to craft an explicit policy on ethics and standards, now featured prominently on our Web site and as an explicit part of our relationship with the journalists we fund. We have also added the position of senior editor to our staff, reflecting the importance of this part of our work.

RELATED ARTICLE

“From War Zones to Life at Home: Serendipity and Partners Matter”

- Jason MotlaghIncome for Journalists: We began with the naïve assumption that if we covered the costs of getting journalists to the field they would be able to earn a decent income through placement of the resulting stories. We were wrong! We’ve had projects in which we provided $15,000 and up in travel costs and journalists invested weeks or months of work—and national news media outlets have paid $1,000 or less for the articles they have published. An urgent part of our mission has become the identification of income streams for our journalists—from payment for talks we arrange on college campuses to the provision of income within our journalism grants themselves. Pulitzer grantees who have demonstrated their ability to produce great work—journalists like Jason Motlagh—know they can count on us for the quick funding decisions that enable them to seize reporting opportunities. Others, among them radio documentary producer Dan Grossman, have raised significant funding by using the Pulitzer Center as fiscal agent and by incorporating their work within our coverage of specific issues. The basic argument is simple: Good journalism costs money. It has value. Those who create it should be paid.

Local Voices: In my career at the Post-Dispatch I prepared dozens of enterprise projects around the world, traveling to areas of interest for weeks at a time but never stationed permanently in any of the places I covered. It was parachute journalism, to be sure, but undertaken with a commitment to providing both a fresh perspective and sufficient reporting to ensure against superficial results. Many of the projects we fund follow this model, with the aim of producing print and broadcast journalism that will speak to the largest possible American audience.

RELATED ARTICLES

“Should Local Voices Bring Us Foreign News?”

- Solana Larsen

“Brutal Censorship: Targeting Russian Journalists”

“Journalists Who Dared to Report—Before They Fled or Were Murdered”

- Fatima TlisovaYet as we expand, we are conscious of the need to incorporate authoritative local voices from the countries we cover, indigenous journalists who speak from an experience no visitor can match. Our collaboration this year on food insecurity issues with Global Voices Online, the international community of bloggers, is one example of this approach. Another is our partnership with Nieman Reports to support the work of Fatima Tlisova, featured in this issue, on the persecution of journalists in her home region of Russia’s North Caucasus.

Tlisova was given political asylum in this country and spent two years at Harvard, first at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy and then as a Nieman Fellow. We were introduced to her with the help of Persephone Miel, a senior journalist at Internews, a former fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, and constant champion of journalists struggling against great odds in repressive regions of the world. Miel died earlier this summer. She asked that Internews and the Pulitzer Center create a fellowship in her honor that would provide Pulitzer Center reporting fellowships for journalists like Tlisova.

It’s an honor to be part of this initiative, so close in spirit to our commitment to “illuminate dark places” and “interpret these troubled times.” We hope this fellowship will be an integral part of our work for years to come.

Jon Sawyer is the founding director of the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, a Washington-based nonprofit that promotes in-depth engagement with global affairs through its sponsorship of quality international journalism across all media platforms and an innovative program of outreach and education.