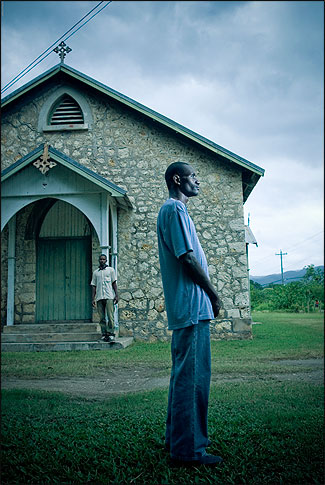

Poems and photographs work together in the multimedia project, “Hope: Living & Loving with HIV in Jamaica.” Photo by Joshua Cogan (www.joshuacogan.com).

RELATED ARTICLE

“A Photographer’s Journey Begins With a Coffin”

– Andre Lambertson (From Fall 2001)Poet and journalist Kwame Dawes has traveled to Jamaica and Haiti to work on multimedia projects for the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. In combining his poetry with the images of photographers Joshua Cogan and Andre Lambertson, the life circumstances of people living with HIV/AIDS are revealed. Dawes describes these photographers’ work as “rich with the possibility of language” and his poems as providing a “dialogue with their dance of light and moment.” The multimedia Web site for “Hope: Living & Loving with HIV in Jamaica,” a collaboration with Cogan, was awarded an Emmy last year in recognition of its new approach to news and documentary programming. In this essay, Dawes, who is distinguished poet in residence at the University of South Carolina, writes about the interwoven roles he experiences as a witness—as poet and journalist.

No matter how often I do it, I am unable to shake the nagging sense that an interview I am about to conduct is not going to reveal anything interesting or anything that will hold the interest of anyone else. At the heart of the fear is the concern that the person I am about to interview will not want to say anything at all. This is especially so when I am about to do an interview involving matters that can be intimate and deeply private. My fear is not merely academic. I have interviewed people who simply would not speak. I could tell quite quickly that they had either misunderstood what the interview was about or they had changed their minds.

But as a poet everything is useful material. Such material might be drawn from a long interview filled with brave details about violence against homosexuals and risk-taking honesty about the person’s own life, as I did in Jamaica two years ago, words I never

heard again after the cameraman somehow lost the videotape. Or from talking with the self-centered head of a major organization in Haiti who gave me pat answers and spoke as if he had done this interview a million times before, which, alas, he might have; he gave one hint of something new and interesting in all that he said. Yet, as a poet, I am always storing material for some use.

This seems to present a false parallel between the making of poems and the writing of a news report—journalism, in a word. But this is not the case. Poetry and the collecting of material for poetry are never self-conscious. Indeed, the material that I collect for poetry is never collected for poetry but collected by me to keep track of where I have been, who I have been with, and how I feel about what I have seen. I am collecting, yes, but not consciously. What I am doing is responding as a human being to what I am seeing and hearing and trying to find ways of keeping track of what I am discovering.

I’ve recently made two reporting trips to Haiti. When I came home after the first trip I did not know if I would find anything to write about in poems. I knew I had a lot to write about in terms of straight journalistic pieces, but a poem is not the “story,” it is something deeper; it has to do with an image, an image that can be both something seen or something that happens, a snippet of a narrative. It can be a detail, a scent, a question, a fear, a desire. I come to the poems without answers. By now I’ve seen and felt enough in my time in Haiti to write many poems, but the odd thing is that when I look at the poems I have since written, I do not have a clear recollection of making any mental notes of what drove them to existence while I was on the ground. I never refer to notes when I am writing the poems.

If someone said to me, write about what you feel about HIV/AIDS in Jamaica, I would say much more than the poem “Coffee Break,” which is part of our multimedia project, “Hope: Living & Loving with HIV in Jamaica.” I am not sure what this poem says about HIV/AIDS in Jamaica yet it is about a man who dies of this disease there so in that sense it is a poem about what I feel about HIV/AIDS in Jamaica. But nothing happens in that poem. Nothing extraordinary. A man dies of AIDS. The only reason for the poem is the implied shock felt by a man who sees death everyday as he sees this one man die. So people die easily. What does that mean? Why is that important? Why is that helpful in making us understand the disease in Jamaica? I don’t know. But I do know that I wrote the poem because when I heard the story told to me my eyes filled with tears and I stored it in my head not as a note for a poem but as a moment of feeling and understanding that I wanted to keep with me for as long as I could.

I did not write about this man’s death in a journalistic piece nor did I say a great deal about it even as I told people about what I learned about AIDS in Jamaica. But it came back to me when I started to write a poem. It came back to me whole and fully formed. And I transported myself to the moment, a moment I did not actually witness, and so a moment I invented. The moment, which sits at the heart of the poem, is that final image: “the balloons sat lightly/on his still lap.” What actually happened may have been more interesting, but for me the thought of his last breath caught in the balloon that seems strangely alive despite his passing is a haunting image that came to me at once when I started to write the poem.

The poems I have written about Haiti come from these “grace moments”—moments of silence and seeming insignificance. I am taking a chance to even suggest that therefore these poems are about a subject, about something that we understand in a journalistic way. Yet they are exactly that because they are about my witnessing not intellectually but mostly emotionally what is happening before me. I stand as a witness to the silences—to what goes unspoken and ignored—to the things that float away as if insubstantial but that are filled with the simple breaths of people trying to make sense of their existence. This act of witnessing allows us to reach to other levels of meaning that can only be reached through the poem.

In a sense, my poems come out of a hunger to be in some kind of conversation. Like the interview, though, I come to the page nervously. I have no idea whether the page will yield a poem, and I have no idea what that poem will be. It is reassuring to know that anxiety will always be my state before any kind of story.

If someone is seeking to discover the core of my experience researching, interviewing and writing about HIV/AIDS in Jamaica and Haiti, one will find it in my poems. They are unguarded and by being poems their loyalty is to themselves and to my emotional and intellectual truth—as limited as that might be. In that place I try to be as open a witness as I can be. This is not the place to find out the facts of HIV/AIDS in these countries, but it is where one can find a way to see the way that disease enters the human imagination. This has to have some value.

Coffee Break

By Kwame DawesIt was Christmas time,

the balloons needed blowing,

and so in the evening

we sat together to blow

balloons and tell jokes,

and the cool air off the hills

made me think of coffee,

so I said, “Coffee would be nice,”

and he said, “Yes, coffee

would be nice,” and smiled

as his thin fingers pulled

the balloons from the plastic bags;

so I went for coffee,

and it takes a few minutes

to make the coffee

and I did not know

if he wanted cow’s milk

or condensed milk,

and when I came out

to ask him, he was gone,

just like that, in the time

it took me to think,

cow’s milk or condensed;

the balloons sat lightly

on his still lap.

Reprinted with permission from “Hope’s Hospice and Other Poems,” published by Peepal Tree Press in 2009.