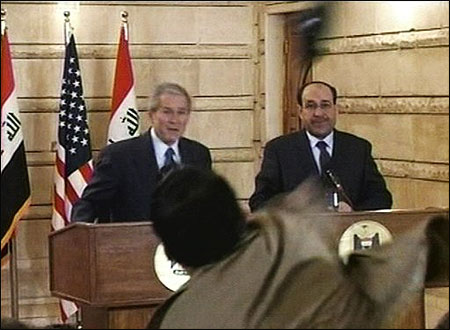

In December 2008, Iraqi reporter Muntader al-Zaidi threw a shoe at President George W. Bush during a news conference with Iraq Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki in Baghdad, Iraq. Photo by The Associated Press/APTN video.

One thing is certain: Decide to work as a trainer with international journalists from areas of conflict, such as the Middle East or the Balkans, and you will share the pain of their stress, the trauma of their physical injuries, and the heavy price they and their families pay because of their work. Be prepared to expend much time and psychic energy in assisting them, and realize your efforts won’t always be successful.

There was the time when Iraqi journalist Yossef al-Naale received a desperate phone call from his wife, who frantically told him that he must not return to Iraq. His young son had innocently told schoolmates his father was visiting with other journalists in the United States in a workshop I directed. Word had reached his political enemies, and when al-Naale finally did return home after delaying in Jordan, he was badly beaten and nearly killed. Beginning in 2005, it took years until with the help of friends—and a series of my advisory phone calls and e-mails—he was finally able to craft a petition that gained him and his family political asylum in Belgium.

Last April I received an e-mail from him letting me know that he and his family were safely living not far from Brussels. He added: “I will not forget you are the man … who deserves all my respect. I am lucky when I met you so I see [you] even as a father, and a brother and a great teacher to me.”

He and I had spent two intensive weeks in the United States with eight other Iraqi journalists. Our time together included a surprise White House visit with President George W. Bush and several Department of State officials, with a candid exchange about the difficulties these journalists perceived in the new Iraqi Constitution that was about to be voted on. (The group had split in a vote about whether they could safely accept the White House invitation; they agreed to do so only with the promise of no publicity.) At the end of our visit, we posed for photos with the President in the Oval Office, but those could not be shown. Leaving the White House, our escort asked a TV cameraman on routine watch outside to cap his lens to protect the identity of the Iraqis.

A Journalist Seeks Help

My encounter with another journalist in Beirut in November 2008 had a far different outcome. I was conducting a weeklong series of workshop lectures on the impact of the Internet and new media for about 30 journalists from Iraq. After class, one of the participants, Muntader al-Zaidi, a Baghdad-based Iraqi TV reporter with Al Baghdadia, approached me and shared with me that in the previous year he’d been kidnapped, then released unharmed a few days later by one of the militant factions. He’d also been detained by U.S. forces and released. According to family members, al-Zaidi was deeply affected by his coverage of the death and suffering of civilians, especially women and children. In Beirut, he asked me for help: he said he was nervous, unable to sleep at night, and was suffering from post-traumatic stress. Could I find him help in the United States?

He brought me clippings about his kidnapping, gave me his contact information, and all week we discussed options. Two of his colleagues had been killed, and more recently, two others had died while doing their work. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that in 2008 Iraq was the deadliest location to work as a journalist with 11 killed, down from 32 the previous year.

Al-Zaidi and I strategized about where he might get help; perhaps CPJ, an American university, or the Cairo-owned satellite TV station where he worked. When I left Beirut, I was planning on following through on our discussions when a few weeks later, al-Zaidi in a fit of rage threw his shoes at President Bush during a December 2008 press conference in Baghdad. In Arabic he shouted: “This is a gift from the Iraqis. This is the farewell kiss, you dog!” Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki tried to shield the President as the second shoe flew by and al-Zaidi shouted: “This is from the widows, the orphans, and those who were killed in Iraq.”

Instantly, the TV journalist became a hero to many in the Arab world, but to others his actions were a deep affront to Arab hospitality. In May 2009 I wrote a Quill magazine cover story about this foolish action that endangered him, the President (who nimbly ducked out of harm’s way), and the other journalists present. His action that day also dangerously blurred the line of impartiality that journalists must never cross without jeopardizing themselves and their colleagues.

I wonder how different things would have turned out if I could have found help for al-Zaidi. If assistance came sooner for his possible post-traumatic stress, maybe the shoe-throwing incident would not have taken place. Facing a possible 15 years in prison, he was sentenced to three years, later reduced to one year. Perhaps consideration of post-traumatic stress might have kept him from jail all together. There are times, still, when I even fantasize about former President Bush, who dismissed the incident with humor, meeting and reconciling with this young journalist, who was released in the fall after serving nine months and claiming that he was tortured in prison.

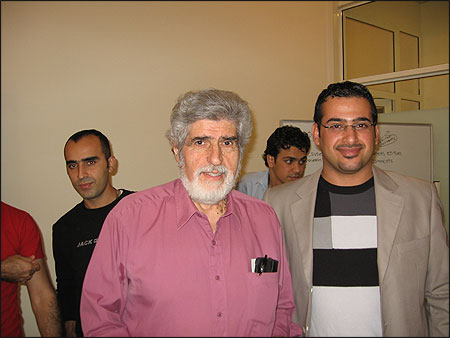

Muntader al-Zaidi, right, attended a series of workshops taught by journalism professor Jerome Aumente, left.

Dealing With Danger

Beginning in Poland in 1989, with the election of Solidarity and the fall of Communism, I have led dozens of training programs for journalists in the U.S., Central and Eastern Europe, and the Balkans. In 1999, on a trip to Bosnia-Herzegovina, I was scheduled to spend time with Zeljko Kopanja, a newspaper editor and broadcast owner who had participated in one of my workshops. Two days before our meeting in Banja Luka, he started his car. It was rigged with explosives. When his car blew up, he lost both of his legs.

When we met later, his prosthetic legs were not working properly and he asked for my help. I contacted Ann Cooper, then CPJ’s director, and she acted swiftly. Money was raised for new prosthetics and I worked with an association of journalists in Italy to get him funds for rehabilitation and travel in Vienna. Sometime later I met Kopanja in New York City just hours before he received the CPJ’s International Press Freedom Award for his reporting of human rights abuses and corruption. In Bosnia, he is seen as a hero to the many young journalists whom he has urged to keep doing tough, investigative reporting.

In 1998, during a series of workshops for opposition print and broadcast, I met radio station owner Nikola Djuric in Nis, Serbia. A little while later Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic banned him from returning home and his station was seized. Through the CPJ, help was found for him and his family in the United States, including a Nieman Fellowship and subsequent work. Two years ago, when I returned to Serbia for workshops, I found many of the opposition media to Milosevic, including B92 radio, TV and the Internet, to be a flourishing force for independent media.

The takeaway lesson is about the need for those training international journalists to be engaged beyond the curriculum in embracing the human dimensions of what it means to be a journalist. Counseling journalists in peril and those coping with traumatic stress, physical injuries, and the death of colleagues is an essential part of our job. Then we need to be prepared to act, which means keeping good contact records with journalists and with organizations whose mission includes helping those in trouble and following up on offers of assistance. It also means not over-promising but candidly marking the limits of what can be done.

Reaching Out to Help Journalists

In response to my Quill article, a former journalist, now teaching, e-mailed me to say she’d experienced post-traumatic stress in covering child welfare deaths in the United States. She urged that we not forget journalists like her who also need help. With the news media resembling the intensive care ward of an industry in steep decline, such reminders seem even more relevant.

To address these needs, foundations should increase their aid to journalists who are emotionally or physically harmed. Assistance, too, is sometimes necessary for their families, as the Iraqi experience taught me. Western reporters rely heavily on nationals in Iraq and Afghanistan to help them gather information, and this exposes these individuals and their families to grave danger. They will require help in obtaining emergency travel visas and need financial assistance as they confront revengeful retribution. For example, the Obama administration should be pushed to provide special immigration status to these journalist colleagues whose lives have been endangered.

In 2001, CPJ created a Journalist Assistance Program for the purpose of aiding journalists in peril who were in hiding or in exile to escape death threats. Direct assistance of nearly $560,000 in emergency funding has gone from CPJ to more than 374 journalists from 50 countries. An additional $860,000 in foundation grants has been administered by CPJ to support academic fellowship programs for journalists in peril. [The Nieman Foundation participates in this effort.] CPJ’s involvement stretches further to include:

- Maintaining a CPJ Distress Fund, which raises cash for journalists with extensive needs and places endangered journalists at leading universities or training projects throughout the world

- Lobbying governments and international agencies to secure refugee, emergency resettlement, or asylum status for journalists

- Providing medical treatment to journalists forced to flee their country under threat or following attack or imprisonment

- Assisting families of imprisoned journalists

- Nominating journalists for awards recognizing their courageous work

- Helping find assistance with legal fees for prosecuted journalists.

More journalists today are in peril, and their need for assistance is increasing. Reporters have done an extraordinary job of raising the public’s awareness of the debilitating impact that violence and trauma have on soldiers. Now it’s time to focus the spotlight on them—and from within our community find the will and the ways to shield them from danger, when possible, and offer them a helping hand.

Jerome Aumente, a 1968 Nieman Fellow, is distinguished professor emeritus and special counselor to the dean at the School of Communication and Information (SC&I) at Rutgers University. He was founding chairman of the Department of Journalism and Media Studies and founding director of the Journalism Resources Institute, both in SC&I.