When Jeff MacNelly, the popular and influential editorial cartoonist at the Chicago Tribune, died in June of 2000, cartoonists on a listserv debated how long a period would be considered respectful before sending in their resumes. A week? A month? Five minutes?

Turns out it wouldn’t have mattered. Nearly five years after the three-time Pulitzer Prize-winner’s death, the Tribune has yet to hire a full-time cartoonist to the staff position MacNelly left behind. Editorial page editor Bruce Dold has said—repeatedly—the Tribune would like to hire a suitable permanent replacement. And while a number have interviewed with the newspaper during the past half decade and rumors of an impending hiring surface regularly, among cartoonists it has reached a point where the offer of staff job from the Tribune has become akin to that of buying a certain bridge.

How is it that one of the largest newspapers in America can’t—or won’t—fill such a prominent position? It is a question editorial cartoonists discuss among themselves repeatedly: They see it not simply as an open job slot, but a symptom of a larger, more serious problem. If wide syndication is considered the gauge of success in this business, the full-time staff job is the baseline from where the measurement has traditionally been made—and one in increasing danger of being erased.

Vanishing Jobs

Earlier this year I edited “Attack of the Political Cartoonists,” a compendium of artists working today. Between the time the book went to press and appeared in bookstores, four of the cartoonists mentioned in its pages had been forced out of their staff positions.

Frequent shakeups are not unusual in the news industry but, unlike reporters, photographers and editors, editorial cartoon jobs are increasingly left unfilled or are eliminated entirely after a cartoonist leaves a paper. Today there are fewer than 90 cartoonists working full time for American newspapers, down from a peak of nearly 200 in the early 1980’s, when the craft benefited from the same influx and interest the post-Watergate years brought to journalism.

Media consolidation, newspapers folding, tightening budgets—all have contributed to the erosion of viable outlets. The pressure for double-digit profits at chain-owned papers has publishers looking around for expendable personnel, and who’s more expendable than the ink-stained wretch hunched over in the corner drawing silly pictures?

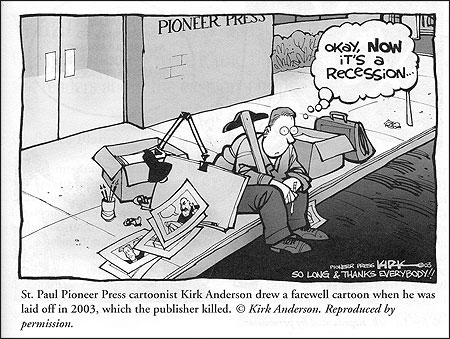

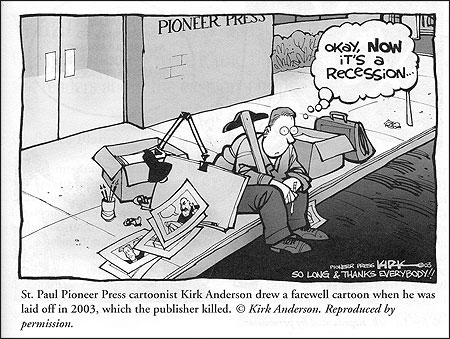

When Kirk Anderson was laid off from the St. Paul Pioneer Press in April 2003, he pointed out in a farewell e-mail to coworkers that were the choice his, he’d cut the private service that tends the plants in the publisher’s office “before I’d cut a local cartoonist.” Anderson added, “Is the position of local cartoonist really valued less than office plants?” (Anderson’s letter, which also included a blistering condemnation of corporate ownership of newspapers, and Knight Ridder CEO Tony Ridder in particular, ended up on the popular Romenesko Web site. Soon after, the Pioneer Press publisher killed Anderson’s final cartoon, and Ridder himself tried to quash a story about the layoff on Editor & Publisher’s Web site.)

Of course, payroll streamlining isn’t the only reason jobs are disappearing. Bottom-line mentality and a concern for slipping circulation can drive publishers and editors to fear controversy of any sort (and if there’s one thing editorial cartoons excel at attracting …). Given today’s environment of cultural sensitivity, an increasingly polarized electorate and technology that allows swift and coordinated responses from angry readers around the planet, many editors would rather not rock the boat to begin with and quickly fold when uproar somehow manages to land on their desk.

“Editors want us to be ‘fair,’ not opinionated,” says Steve Benson, cartoonist for The Arizona Republic. They say they want hard-hitting work, but “when cartoonists do hand in strong cartoons, an editor is just as likely to kill it to avoid offending readers and losing advertisers.”

.jpg)

Far worse, at least to some cartoonists, is the editor who insists on watering down the commentary in order to be equal and balanced, altering content to such a degree the point of the cartoon is lost. John Sherffius surprised everyone a year ago when he resigned suddenly from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch over what he saw as an unacceptable amount of interference from his editor. According to a report in The New York Times (which, by the way, hasn’t had a staff cartoonist since 1958), Sherffius quit over a “culmination of disagreements with Ellen Soeteber, the editor of the newspaper, over what she viewed as excessive criticism of President Bush and Republicans.”

The proverbial final straw came when Sherffius did a cartoon about the GOP-controlled House celebrating after passing a pork barrel-laden appropriations bill that benefited Republicans. He was told to alter it by changing the pig pictured in the piece into a donkey so both parties were represented. Even after Sherffius acquiesced and redrew the cartoon, Soeteber was heard to complain it was still “too one-sided.” (Apparently the donkey wasn’t happy enough.) By now, the original intent was completely gutted. He redrew the cartoon a third time, handed it in and resigned the next day.

“Editors ask for changes all the time,” Sherffius told The New York Times. “That’s fine. It’s part of the process …. I felt this was a little different.”

Given the job market, it is the rare cartoonist indeed who resigns on principle. More often they are pushed out.

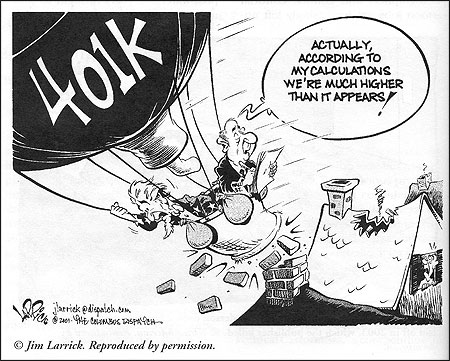

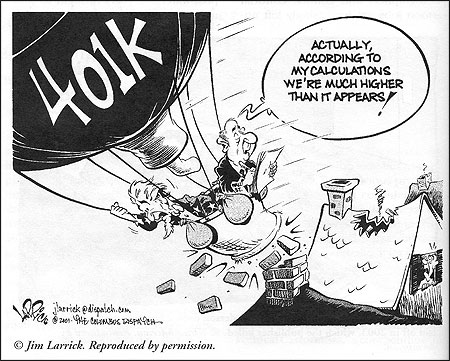

One bright spot over the years has been family-owned papers that, whatever their circulation, often had a local cartoonist on staff as a matter of civic pride. Yet even among independent papers with a long tradition of editorial cartooning, the squeeze is on, resulting in something like musical chairs with cartoonists forced to fight over dwindling seats. In May, The Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch unceremoniously shoved aside 22-year veteran Jim Larrick so they could make room to hire Jeff Stahler away from The Cincinnati Post. Stahler only took the offer after it was apparent that the Post (and his job) wouldn’t be around after a Joint Operating Agreement with The Cincinnati Enquirer expires in 2007.

Whether or not they can find a fulltime gig, most cartoonists still continue to draw. The majority of people getting published today have cobbled together a career of sorts, freelancing, doing ’toons on the side, or working for a newspaper or magazine in other capacities with the opportunity to get in an occasional cartoon. Even if they have been cut loose by a paper, many scrape by with freelance work while continuing to provide material for their syndicate. A few, like Ted Rall or Pulitzer Prize-winner Ann Telnaes, have never worked for a newspaper, instead laboriously building up a full-time job through syndication.

But among cartoonists, syndication itself is a thorny issue. What is a solution for some, others see as a problem: Why should any paper hire a full-time staffer, especially given the decreasing costs of syndicated material and increasingly easy access to it? The story goes that in the late 1990’s, The Village Voice fired their long-time cartoonist Jules Feiffer because they said they could no longer afford to pay his salary—but they still wanted to run his cartoons and just planned to buy them from his syndicate (albeit without benefits, pension or support structure of a full-time employee).

Future Directions

If it often sounds like we are fighting a rear-guard action, well, the sentiment is part of our collective DNA. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC), the group to which the majority of politically oriented cartoonists belong, formed in 1957 in reaction to an article in The Saturday Review stating political cartooning was dead. “The Rise and Fall of the Political Cartoon” so offended John Stampone of the Army Times, he and a small band of fellow cartoonists set out to prove the article wrong and set up the AAEC to stimulate more public interest about editorial cartoons and closer contacts among cartoonists.

We’ve been battling that sense of doom and gloom ever since. In a panel discussion at the 2002 AAEC convention, Steve Hess, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and coauthor of “Drawn & Quartered: The History of American Political Cartoons,” said one has to try to keep things in perspective. “For as long as I’ve been going to [newspaper industry] conventions, they reminded me of Buggy Whip conventions.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Animation and the Political Cartoon"

- Mark FioreWith the rise of the Internet over the past decade, cartoonists have begun to ask if their fate must be tied to that of newsprint. So far, only one cartoonist—Mark Fiore—has left print entirely behind and is the first person to make a living creating weekly animated political cartoons for the Web. As for the rest, while the Internet provides easier distribution of their work and a much wider audience, they are still—just like everyone else—figuring out how to make it pay. Until that happens, we must depend on newspapers, even as they treat the majority of us as temporary workers.

Not all openings gather dust. After Washington Post legend Herbert Block, a.k.a. Herblock, died in October 2001, the Post thought his position too important to lie vacant and set out almost immediately to find his successor, eventually wooing Pulitzer Prize-winner Tom Toles from his hometown paper, The Buffalo News. Many thought the News would let Toles’s old position languish, and while it took them over two years to make a decision, in an encouraging move this past August they hired an enthusiastic grad after his internship with the paper.

As for the Chicago Tribune, it continues to fill their op-ed page with syndicated material and occasionally requests cartoons on specific issues from freelancers. In January 2004, they opened a permanent exhibit of Jeff MacNelly’ s work on the 24th floor of the Tribune Tower. A Tribune Media Services vice president told Editor & Publisher Online, “It’s a reflection of the esteem in which Jeff was held here.”

Mike Ritter, then the president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, responded in an interview in the Chicago Reader: “Putting up a cartoon show as a permanent exhibit but not hiring a new cartoonist comes off as a tombstone more than anything else.”

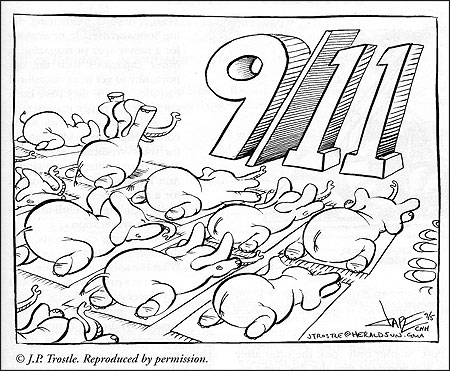

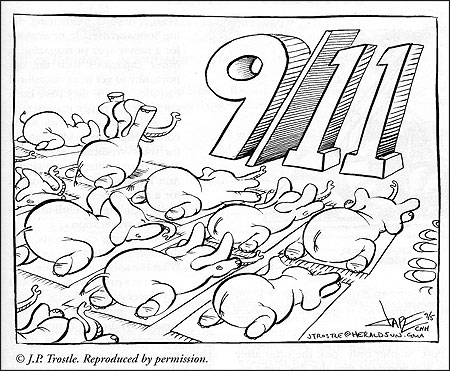

J.P Trostle is the editor of the Notebook, the quarterly magazine of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists and the book “Attack of the Political Cartoonists: Insights & Assaults from Today’s Editorial Pages.” He also draws an occasional cartoon for The Chapel Hill Herald in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Turns out it wouldn’t have mattered. Nearly five years after the three-time Pulitzer Prize-winner’s death, the Tribune has yet to hire a full-time cartoonist to the staff position MacNelly left behind. Editorial page editor Bruce Dold has said—repeatedly—the Tribune would like to hire a suitable permanent replacement. And while a number have interviewed with the newspaper during the past half decade and rumors of an impending hiring surface regularly, among cartoonists it has reached a point where the offer of staff job from the Tribune has become akin to that of buying a certain bridge.

How is it that one of the largest newspapers in America can’t—or won’t—fill such a prominent position? It is a question editorial cartoonists discuss among themselves repeatedly: They see it not simply as an open job slot, but a symptom of a larger, more serious problem. If wide syndication is considered the gauge of success in this business, the full-time staff job is the baseline from where the measurement has traditionally been made—and one in increasing danger of being erased.

Vanishing Jobs

Earlier this year I edited “Attack of the Political Cartoonists,” a compendium of artists working today. Between the time the book went to press and appeared in bookstores, four of the cartoonists mentioned in its pages had been forced out of their staff positions.

Frequent shakeups are not unusual in the news industry but, unlike reporters, photographers and editors, editorial cartoon jobs are increasingly left unfilled or are eliminated entirely after a cartoonist leaves a paper. Today there are fewer than 90 cartoonists working full time for American newspapers, down from a peak of nearly 200 in the early 1980’s, when the craft benefited from the same influx and interest the post-Watergate years brought to journalism.

Media consolidation, newspapers folding, tightening budgets—all have contributed to the erosion of viable outlets. The pressure for double-digit profits at chain-owned papers has publishers looking around for expendable personnel, and who’s more expendable than the ink-stained wretch hunched over in the corner drawing silly pictures?

When Kirk Anderson was laid off from the St. Paul Pioneer Press in April 2003, he pointed out in a farewell e-mail to coworkers that were the choice his, he’d cut the private service that tends the plants in the publisher’s office “before I’d cut a local cartoonist.” Anderson added, “Is the position of local cartoonist really valued less than office plants?” (Anderson’s letter, which also included a blistering condemnation of corporate ownership of newspapers, and Knight Ridder CEO Tony Ridder in particular, ended up on the popular Romenesko Web site. Soon after, the Pioneer Press publisher killed Anderson’s final cartoon, and Ridder himself tried to quash a story about the layoff on Editor & Publisher’s Web site.)

Of course, payroll streamlining isn’t the only reason jobs are disappearing. Bottom-line mentality and a concern for slipping circulation can drive publishers and editors to fear controversy of any sort (and if there’s one thing editorial cartoons excel at attracting …). Given today’s environment of cultural sensitivity, an increasingly polarized electorate and technology that allows swift and coordinated responses from angry readers around the planet, many editors would rather not rock the boat to begin with and quickly fold when uproar somehow manages to land on their desk.

“Editors want us to be ‘fair,’ not opinionated,” says Steve Benson, cartoonist for The Arizona Republic. They say they want hard-hitting work, but “when cartoonists do hand in strong cartoons, an editor is just as likely to kill it to avoid offending readers and losing advertisers.”

.jpg)

Far worse, at least to some cartoonists, is the editor who insists on watering down the commentary in order to be equal and balanced, altering content to such a degree the point of the cartoon is lost. John Sherffius surprised everyone a year ago when he resigned suddenly from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch over what he saw as an unacceptable amount of interference from his editor. According to a report in The New York Times (which, by the way, hasn’t had a staff cartoonist since 1958), Sherffius quit over a “culmination of disagreements with Ellen Soeteber, the editor of the newspaper, over what she viewed as excessive criticism of President Bush and Republicans.”

The proverbial final straw came when Sherffius did a cartoon about the GOP-controlled House celebrating after passing a pork barrel-laden appropriations bill that benefited Republicans. He was told to alter it by changing the pig pictured in the piece into a donkey so both parties were represented. Even after Sherffius acquiesced and redrew the cartoon, Soeteber was heard to complain it was still “too one-sided.” (Apparently the donkey wasn’t happy enough.) By now, the original intent was completely gutted. He redrew the cartoon a third time, handed it in and resigned the next day.

“Editors ask for changes all the time,” Sherffius told The New York Times. “That’s fine. It’s part of the process …. I felt this was a little different.”

Given the job market, it is the rare cartoonist indeed who resigns on principle. More often they are pushed out.

One bright spot over the years has been family-owned papers that, whatever their circulation, often had a local cartoonist on staff as a matter of civic pride. Yet even among independent papers with a long tradition of editorial cartooning, the squeeze is on, resulting in something like musical chairs with cartoonists forced to fight over dwindling seats. In May, The Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch unceremoniously shoved aside 22-year veteran Jim Larrick so they could make room to hire Jeff Stahler away from The Cincinnati Post. Stahler only took the offer after it was apparent that the Post (and his job) wouldn’t be around after a Joint Operating Agreement with The Cincinnati Enquirer expires in 2007.

Whether or not they can find a fulltime gig, most cartoonists still continue to draw. The majority of people getting published today have cobbled together a career of sorts, freelancing, doing ’toons on the side, or working for a newspaper or magazine in other capacities with the opportunity to get in an occasional cartoon. Even if they have been cut loose by a paper, many scrape by with freelance work while continuing to provide material for their syndicate. A few, like Ted Rall or Pulitzer Prize-winner Ann Telnaes, have never worked for a newspaper, instead laboriously building up a full-time job through syndication.

But among cartoonists, syndication itself is a thorny issue. What is a solution for some, others see as a problem: Why should any paper hire a full-time staffer, especially given the decreasing costs of syndicated material and increasingly easy access to it? The story goes that in the late 1990’s, The Village Voice fired their long-time cartoonist Jules Feiffer because they said they could no longer afford to pay his salary—but they still wanted to run his cartoons and just planned to buy them from his syndicate (albeit without benefits, pension or support structure of a full-time employee).

Future Directions

If it often sounds like we are fighting a rear-guard action, well, the sentiment is part of our collective DNA. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists (AAEC), the group to which the majority of politically oriented cartoonists belong, formed in 1957 in reaction to an article in The Saturday Review stating political cartooning was dead. “The Rise and Fall of the Political Cartoon” so offended John Stampone of the Army Times, he and a small band of fellow cartoonists set out to prove the article wrong and set up the AAEC to stimulate more public interest about editorial cartoons and closer contacts among cartoonists.

We’ve been battling that sense of doom and gloom ever since. In a panel discussion at the 2002 AAEC convention, Steve Hess, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and coauthor of “Drawn & Quartered: The History of American Political Cartoons,” said one has to try to keep things in perspective. “For as long as I’ve been going to [newspaper industry] conventions, they reminded me of Buggy Whip conventions.”

RELATED ARTICLE

"Animation and the Political Cartoon"

- Mark FioreWith the rise of the Internet over the past decade, cartoonists have begun to ask if their fate must be tied to that of newsprint. So far, only one cartoonist—Mark Fiore—has left print entirely behind and is the first person to make a living creating weekly animated political cartoons for the Web. As for the rest, while the Internet provides easier distribution of their work and a much wider audience, they are still—just like everyone else—figuring out how to make it pay. Until that happens, we must depend on newspapers, even as they treat the majority of us as temporary workers.

Not all openings gather dust. After Washington Post legend Herbert Block, a.k.a. Herblock, died in October 2001, the Post thought his position too important to lie vacant and set out almost immediately to find his successor, eventually wooing Pulitzer Prize-winner Tom Toles from his hometown paper, The Buffalo News. Many thought the News would let Toles’s old position languish, and while it took them over two years to make a decision, in an encouraging move this past August they hired an enthusiastic grad after his internship with the paper.

As for the Chicago Tribune, it continues to fill their op-ed page with syndicated material and occasionally requests cartoons on specific issues from freelancers. In January 2004, they opened a permanent exhibit of Jeff MacNelly’ s work on the 24th floor of the Tribune Tower. A Tribune Media Services vice president told Editor & Publisher Online, “It’s a reflection of the esteem in which Jeff was held here.”

Mike Ritter, then the president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, responded in an interview in the Chicago Reader: “Putting up a cartoon show as a permanent exhibit but not hiring a new cartoonist comes off as a tombstone more than anything else.”

J.P Trostle is the editor of the Notebook, the quarterly magazine of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists and the book “Attack of the Political Cartoonists: Insights & Assaults from Today’s Editorial Pages.” He also draws an occasional cartoon for The Chapel Hill Herald in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.