Shortly after I co-founded Symbolia, a digital publication that merges comic books and journalism, I got an intriguing pitch. Reporter Sarah Mirk wanted to tell the stories of the veterans who had served at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp to help reframe the public understanding of the base and make the “image of Guantánamo become very clear and personal.”

Mirk took on this story because “media about Guantánamo focuses almost exclusively on policy discussions and the opinions of high-ranking decision-makers.” As a result, human impacts as well as the experiences of those working at the facility are “overshadowed.”

I immediately green-lit the story. Mirk instinctively understood what comic book formats can do for journalism. The form makes heady topics intimate and relevant. Issues that are far away become more personal to the reader. In a world of information overload, beautifully crafted, hand-illustrated comics provide clarity and emotional resonance.

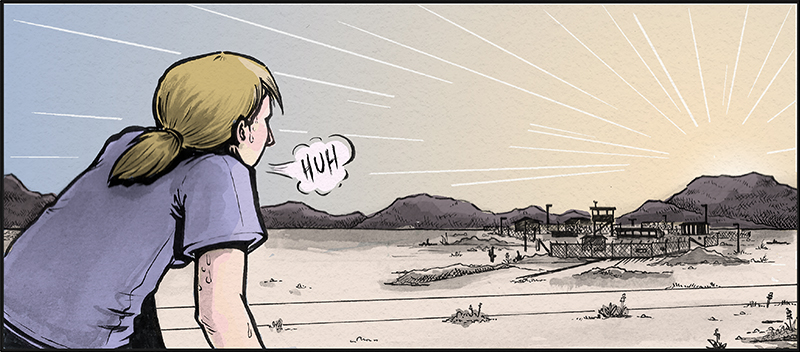

Mirk worked with artist Lucy Bellwood to merge subtle audio, looped animations, and sequential visual narratives in a profile of two Navy veterans. The resulting piece, “Declassified,” is one of the most successful stories from our first year of publishing.

“Declassified” has been syndicated at human-interest journalism outlet Narratively, excerpted at political newsblog Think Progress, distributed as a print minicomic, and translated into French for a forthcoming issue of Swiss start-up Sept.

The work is a powerful case study in how comic books can be successfully used to bring new readers into complex issues. As journalism organizations try to connect with new audiences and innovate online, comic book narratives can work across platforms, engage younger, more visually oriented readers, and transcend cultural borders.

Comics are certainly popular. Graphic novels—the popular term for book-length comics—are one of the fastest growing offerings in contemporary publishing and have been growing in popularity since at least 2008. Amazon recently scooped up digital comics publisher Comixology.

Looking at the print spectrum, BookScan’s 2013 report, which covers about 85 percent of book store sales (not including libraries or comic book stores and few big box stores), shows a nearly 4 percent growth in the number of comic books sold in 2013 and close to 7 percent growth in total revenue. Print sales overall have been shrinking since 2008, according to the 2013 annual report from PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

But why do comics work so well? The secret is in how users consume the content. Comic books make it possible to understand more—and do it faster. Comics theorist and cartoonist Scott McCloud calls it “amplification through simplification,” in which the simplified drawing pares down an image to its “essential meaning.”

This kind of iconic illustration focuses attention on specific ideas and emotions in a process of highly disciplined editorial decision-making. Each stroke of the pen imparts instant meaning because the images are essential and also universal. A few furrows on a character’s brow convey worry. A comic about a veteran’s experiences in Guantánamo Bay becomes a story about a woman that we relate to on an emotional level because we infer complex meaning quickly from the artist’s rendering.

Neuroscientific research supports what narrative nonfiction storytellers instinctively know: Stories with clear, emotionally evocative dramatic arcs are most effective at keeping readers engaged. These stories cause the body to produce chemicals including cortisol, which focuses attention, as well as oxytocin, which is associated with empathy. They also light up areas of the brain linked to understanding others. Neil Cohn of the University of California San Diego, who has been studying comics for more than 10 years, argues that comics can increase overall comprehension as well. “Studies for several decades now have shown that using works written in these visual languages in educational contexts can be helpful for learning,” Cohn says. “The evidence is fairly clear that sequential images (usually plus text) are an effective teaching tool.”

Comics are “great for condensing and coloring stories,” says Roxanne Palmer, who created the story about Ukraine’s YanukovychLeaks investigative reporting project. “You can combine the visual eye candy of a chart with the spine of narrative. You can highlight the humanity of a subject by making their words come out of a face rather than just attached to a name on the page.”

Though comics use simple lines and sparse prose to tell a story, they are anything but simplistic. The best-selling works of Joe Sacco, Marjane Satrapi, Art Spiegelman, and Alison Bechdel contain numerous examples of the successful integration of nonfiction and comics.

As readers increasingly move toward digital content delivered to multiple screens, theories like McCloud’s and findings like Cohn’s are critical in developing new ways to present journalistic content. To create highly engaging content that works well on multiple platforms, don’t rely too heavily on bells and whistles. If the interactive takes away from the core narrative, you don’t need it. Don’t automate a story’s progression like a timed slideshow. Let the reader control the speed and length of time that they spend in the story. Know the core of the story you’d like to convey, and animate that core—in images and words—in ways that evoke empathy and resonate with diverse user groups.

Erin Polgreen is co-founder of Symbolia and has helped many media outlets tell visual stories

Mirk took on this story because “media about Guantánamo focuses almost exclusively on policy discussions and the opinions of high-ranking decision-makers.” As a result, human impacts as well as the experiences of those working at the facility are “overshadowed.”

I immediately green-lit the story. Mirk instinctively understood what comic book formats can do for journalism. The form makes heady topics intimate and relevant. Issues that are far away become more personal to the reader. In a world of information overload, beautifully crafted, hand-illustrated comics provide clarity and emotional resonance.

Mirk worked with artist Lucy Bellwood to merge subtle audio, looped animations, and sequential visual narratives in a profile of two Navy veterans. The resulting piece, “Declassified,” is one of the most successful stories from our first year of publishing.

“Declassified” has been syndicated at human-interest journalism outlet Narratively, excerpted at political newsblog Think Progress, distributed as a print minicomic, and translated into French for a forthcoming issue of Swiss start-up Sept.

The work is a powerful case study in how comic books can be successfully used to bring new readers into complex issues. As journalism organizations try to connect with new audiences and innovate online, comic book narratives can work across platforms, engage younger, more visually oriented readers, and transcend cultural borders.

Comics are certainly popular. Graphic novels—the popular term for book-length comics—are one of the fastest growing offerings in contemporary publishing and have been growing in popularity since at least 2008. Amazon recently scooped up digital comics publisher Comixology.

Looking at the print spectrum, BookScan’s 2013 report, which covers about 85 percent of book store sales (not including libraries or comic book stores and few big box stores), shows a nearly 4 percent growth in the number of comic books sold in 2013 and close to 7 percent growth in total revenue. Print sales overall have been shrinking since 2008, according to the 2013 annual report from PriceWaterhouseCoopers.

But why do comics work so well? The secret is in how users consume the content. Comic books make it possible to understand more—and do it faster. Comics theorist and cartoonist Scott McCloud calls it “amplification through simplification,” in which the simplified drawing pares down an image to its “essential meaning.”

This kind of iconic illustration focuses attention on specific ideas and emotions in a process of highly disciplined editorial decision-making. Each stroke of the pen imparts instant meaning because the images are essential and also universal. A few furrows on a character’s brow convey worry. A comic about a veteran’s experiences in Guantánamo Bay becomes a story about a woman that we relate to on an emotional level because we infer complex meaning quickly from the artist’s rendering.

Neuroscientific research supports what narrative nonfiction storytellers instinctively know: Stories with clear, emotionally evocative dramatic arcs are most effective at keeping readers engaged. These stories cause the body to produce chemicals including cortisol, which focuses attention, as well as oxytocin, which is associated with empathy. They also light up areas of the brain linked to understanding others. Neil Cohn of the University of California San Diego, who has been studying comics for more than 10 years, argues that comics can increase overall comprehension as well. “Studies for several decades now have shown that using works written in these visual languages in educational contexts can be helpful for learning,” Cohn says. “The evidence is fairly clear that sequential images (usually plus text) are an effective teaching tool.”

Comics are “great for condensing and coloring stories,” says Roxanne Palmer, who created the story about Ukraine’s YanukovychLeaks investigative reporting project. “You can combine the visual eye candy of a chart with the spine of narrative. You can highlight the humanity of a subject by making their words come out of a face rather than just attached to a name on the page.”

Though comics use simple lines and sparse prose to tell a story, they are anything but simplistic. The best-selling works of Joe Sacco, Marjane Satrapi, Art Spiegelman, and Alison Bechdel contain numerous examples of the successful integration of nonfiction and comics.

As readers increasingly move toward digital content delivered to multiple screens, theories like McCloud’s and findings like Cohn’s are critical in developing new ways to present journalistic content. To create highly engaging content that works well on multiple platforms, don’t rely too heavily on bells and whistles. If the interactive takes away from the core narrative, you don’t need it. Don’t automate a story’s progression like a timed slideshow. Let the reader control the speed and length of time that they spend in the story. Know the core of the story you’d like to convey, and animate that core—in images and words—in ways that evoke empathy and resonate with diverse user groups.

Erin Polgreen is co-founder of Symbolia and has helped many media outlets tell visual stories