Cartoon by Mark Litzler. Previously printed in the April 2002 Harvard Business Review.

On March 10, 2000, the NASDAQ peaked at 5,048 before beginning its crash to smithereens. This rapid tumble taught both investors and reporters that there is far more to understanding the forces that move the market than the mere reporting of upward gyrations of various stocks. And it made me realize that even though I’d kept myself well informed by reading what I could about the market and its forces, what was happening to me—and I guessed millions like me—was not being covered. This awareness prompted me—who had once been a correspondent and writer for Time—to look for answers to what I wanted to know about the U.S. stock market and then publish what I found. In February 2001 “The Outraged Investor,” my new newspaper column, was born out of my howls of pain as I witnessed my 401(k) funds wither to dust.

One of the first people to listen to my outrage was David Burgin, then the editor of The San Francisco Examiner. Though a novice at investing, when he heard the rancor coming from me as I talked about CNBC, brokerage houses, and stock analysts, he suggested I try my hand at a column. My first outpouring of rage, anguish and frustration touched a nerve in a lot of readers, prompting nearly 100 e-mails. Most were empathetic messages in which people shared their pain and anger and some lessons they’d learned.

Heartened by the public’s response, “The Outraged Investor” continued to reveal some of the destructive market forces that afflict the “little guy,” the kinds of things that the rest of the business media usually ignore. Or at least they did until Enron collapsed.

In my column, I often paint with broad brushstrokes of good and evil the characters that inhabit these stories. Doing this seems to help readers explore complicated trends and issues. The small investor is always a good citizen, someone who works hard, saves money, has a mortgage, raises kids, and invests money for college tuition and retirement. Wall Street Manipulators—the big money backroom forces that are privy to things the small investor will never know and act on—represent evil. An example of evil-doers are New York Stock Exchange floor specialists who, during times of great stress—at the tiptop highs and excruciating lows when the volume dries up—dip into their omnibus accounts and swiftly buy or sell truckloads of stock, enabling them to turn the market.

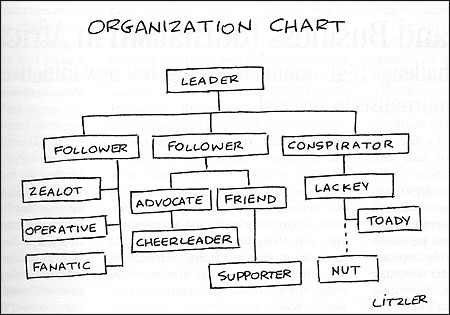

Lurking in the shadows are slippery short-sellers, who pound perfectly good companies to pulp. Behind them are the ranks of crafty hedge fund managers who use every option imaginable to cover their risks. Even more egregious are the evil analysts. Posing as independent researchers, they act as cheerleaders for the investment bankers who, in turn, sweeten their paychecks. Then there are the legions of day traders who, with the aid of the Internet, turned the stock market into the most accessible casino in history. Not all is bleak, however. In the background lurks “Big Daddy,” a.k.a. Alan Greenspan, trying to guide the operation by wrestling inflation and interest rates, the two most important levers influencing the U.S. economy.

“The Outraged Investor” is quick to praise news media outlets when they deserve praise. But that rarely happens. More often, the column attacks the airheads who can read a TelePrompTer but not a balance sheet. Equally vilified are TV news producers who give brokers, fund managers, analysts and CEO’s time, without scrutiny, to push their agendas.

Of course, the business press often lands in the same hamper as show biz reporting, which is considered by many solid journalists to be an arm of the PR industry. My first taste of its anemic condition was in 1988 when I jumped from reporting entertainment stories for Time to writing a business profile on the now-deceased publisher, Robert Maxwell. Soon after the story appeared, Maxwell left a nasty message saying I was no longer invited to attend his yacht parties—a badge of success.

Several months after the Time profile appeared, Maxwell bought the (New York) Daily News. The business press heaped praise on his courage. Hardly a critical word was heard from print and television reporters. Few if any explored Maxwell’s checkered past and shady political history. (The London newspapers had published plenty of stories about his shenanigans in that country.) Because I’d researched his history, I knew that much of his spiel was puffery and invention. At the time, the New York business press was ridiculously kind and nonjudgmental.

With this in mind, I should not have expected much from the business press during the late 1990’s stock run-up. But for some reason, I did, investing at what turned out to be my peril. I had plenty of company, however, since more than a trillion dollars in retirement money has been lost.

Now that I’ve been writing my weekly column, it’s clear to me that the electronic business media rolled over during the late 1990’s. They perpetuated the feeling that for one brief shining moment savvy investors had the opportunity of a lifetime, particularly when it came to investing in the Internet revolution. Investing in young technology companies was akin to winning the lottery, only with better odds, they were told. During those heady times CNBC’s ratings climbed, and business magazines were thick with advertisements. Dot-com billboards sprouted on urban streets where the wealthy congregate and in academic enclaves. Newsweeklies and big-city newspapers joined the party.

To be fair, the traditional print media, most certainly Barron’s and The Wall Street Journal, were wisely circumspect. Hardly a week went by that Barron’s Alan Abelson didn’t berate CNBC and remind investors of the tulip bulb craze, when 17th century Dutch investors bid up the price of tulip bulbs only to see that market crash. But the advice of these old fogies was drowned out by the fast-paced talk of television that barely cracked the veneer of what was going on. Reporters spewed numbers, but passed along to the small investor little good information about what might drive those numbers.

A more accurate slogan for much of business news is “news you can’t use.” The market anticipates, while much of business journalism reflects on what’s already happened. By the time the media alerts you to a trend, there’s already been a seismic shift. (For the investor, it’s time to pull money out, not put it in.) With technology, a lot of the business press pushed the story line that its future was immune to economic forces, repeating the “buy and hold” mantra endlessly. Long-term investors know that timing the market is critical—the key to success.

Many small investors are abandoning the market, prompted in part by not being able to find the information they need or to trust the information they find in the coverage of business and the market. Because free markets can’t thrive under the yoke of excessive regulation, business journalists, acting as watchdogs, become the vital force necessary to keep the capitalist system on track.

What “The Outraged Investor” does is to play the watchdog role for the small investors, spotting scams and pyramid schemes and pointing out why the “big guys” are making money while they—the little guys—are losing ground. What I do is try to level the playing field by making some of the hidden traps more obvious. By doing this, my column nips at the heels of the stock market manipulators in the hope of showing the little guy how to make an honest gain.

Martha Smilgis was a writer and correspondent for Time and a bureau chief for People. Her column, “The Outraged Investor,” appeared weekly in The San Francisco Examiner.