One letter of the alphabet can represent hundreds of years of the suppression of Ukrainian identity. I carry such a letter everywhere I go: the “s” in my last name, Beskorovainyi. In the Ukrainian language, the prefix "bes" doesn't exist; the correct Ukrainian spelling is with the letter "z." The prefix "bes," however, is common in Russian. So is my last name Russian or Ukrainian?

The surprising thing is, even though I had struggled for years with clerks, teachers, and officials always questioning if there was a mistake in the spelling of my last name, I had never once questioned it myself — until I was about to get married. My wife-to-be was eager for me to get to the bottom of this mystery, as she did not want to assume my last name as her own if it contained a mistake.

I went to the archives to find out, and after a meticulous search, I stumbled upon proof in the birth records of my great-grandfather. His name had been written with a "z."

My search for the origins of my last name led me to the discovery that “Russification” of Ukrainian last names had been a common practice, especially after World War II, when Ukrainians were registered in the Red Army. Sometimes, clerks at the registry would make the change on purpose; in other cases, the initiative came from the people themselves. Having a Russian-sounding last name during Soviet times could help you climb the ladder faster, or ensure you wouldn't be marginalized.

Up until that time I had been oblivious to the origin of my surname — or, to use a phrase coined by Robert Proctor, a historian of scientific controversies, I had been practicing "ignorance as a native state." Why?

During my Nieman year at Harvard, I decided to explore the “why” further, taking a class called Agnotology (the study of ignorance) with Professor Naomi Oreskes. It was there that I learned how to put into words my developing thoughts about the ways ignorance is constructed and perpetuated. I also learned that ignorance isn't necessarily a natural state of being, but is oftentimes constructed through strategies such as deliberate or inadvertent neglect, secrecy or suppression, the destruction of documents, cultural and political selectivity, or trivialization.

Even "facts" in the form of records and documents — which we as journalists so heavily rely on — are, in the words of the anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot, "a narrative of power disguised as innocence." Which records get produced and preserved, and which do not? Who assembles them and how? What narratives are constructed around them? What significance is assigned to them retrospectively?

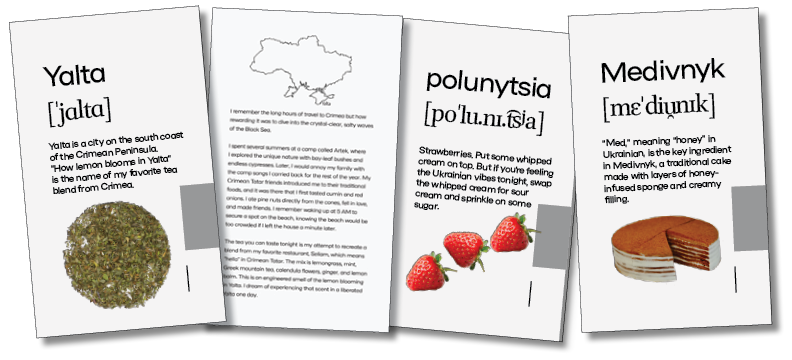

For many years, Ukraine’s story was told for it — by others. The distinctive Ukrainian identity and culture was forcibly assimilated. Ukraine’s intelligentsia was either assassinated or sent to labor camps. Unique letters were removed from the Ukrainian alphabet, and names were changed to be more Russian-sounding. It is no accident that before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia in February 2022, Vladimir Putin published an essay titled, "On the historical unity of Russians and Ukrainians," falsely arguing that the two countries were made up of one people. Prior to the physical destruction of Ukraine, Putin needed to destroy it in people’s imaginations.

Although I found the prevalence of “ignorance as a native state” frustrating, I discovered that curiosity could be the antidote to it. My curiosity led me to science journalism.

My interest in the field came at a time of upheaval for both my country and the media industry. The only major science-related media outlet in Ukraine, National Geographic, had left the country after the 2014 Russian occupation of Crimea — leaving a void for science journalism. We decided to step into that void, and in 2015, I co-founded a science journalism publication called Kunsht, an ancient Ukrainian word which means both “art” and “knowledge.”

Over the decade that followed, I was immersed in stories: from chasing the head of the European Space Agency at the International Astronautical Congress, to hitchhiking around Ukrainian ecovillages, to organizing radio shows about the growing coronavirus threat. With a fantastic, passionate, and mission-driven team, what started with pure intuition and a desire to spark critical thinking in our readers has developed into a vital news outlet fostering an informed, science-based approach that helps people make sense of the world around them.

The impact of our work — and my deep-seated belief in the power of information — was solidified during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a radio show we created about the coronavirus that reached millions of people across 64 Ukrainian cities. We produced educational videos for train passengers, launched awareness campaigns with UNICEF, and produced podcasts on media literacy and the pitfalls of pseudoscience.

In May 2022, we gathered scientists for a Zoom roundtable aimed at understanding how our work as journalists could help scientists at risk in Ukraine. There were an overwhelming number of issues: museum collections had been looted by Russian occupiers, scientific facilities and equipment had been destroyed by missile strikes, and many scientists had been displaced. Out of this meeting, the Science at Risk initiative was born. My journalistic work expanded to help seek solutions to the problems facing Ukraine’s scientific community, and, with support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, which was the first to believe in these efforts, I helped create initiatives to preserve scientists' stories and amplify their voices worldwide.

We have also collaborated with many international journalistic teams to make the stories of Ukrainian science during the war more visible — from the story of a bear evacuation in Vanity Fair magazine to opinion pieces on the destruction of scientific collections for Undark magazine. While at Harvard, I worked on making stories about oppressed Ukrainian scientists more visible to the American academic community through an exhibition at Harvard’s Science Center which was profiled in The Boston Globe. Spending this year in the U.S., during which the American scientific community has been experiencing such turbulence under the Trump administration, has made the story of science at risk in distant Ukraine feel very close to home.

A lot of our work has now shifted to focus on science communications at risk. Whether curating and preserving scientific reporting, compiling databases, or overseeing research risk factors facing the field, I still seek ways to improve science reporting and counter disinformation during wars and social crises.

Over the years, I’ve come to understand what truly drives me: the search for meaning — whether in my personal life, in the wider universe, or in science. I’m drawn to uncovering my own ignorance and helping others do the same. And I’ve learned that information is power: we can either use it intentionally, or have it used against us. I’m dedicated to keep searching for questions I haven’t yet thought to ask — like about the misspelling of my last name. This search is fueled by curiosity, but also by necessity. Because to win the war, we must first win the fight to speak the truth — and to speak for ourselves.