In January, when the sun first rose on David D. Smith’s ownership of Baltimore’s daily newspaper — a broadsheet that in its swashbuckling heyday boasted a full fleet of foreign correspondents, a muscular Washington bureau, and more than 500 reporters and editors — the shrunken newsroom bristled with anxiety about the new boss.

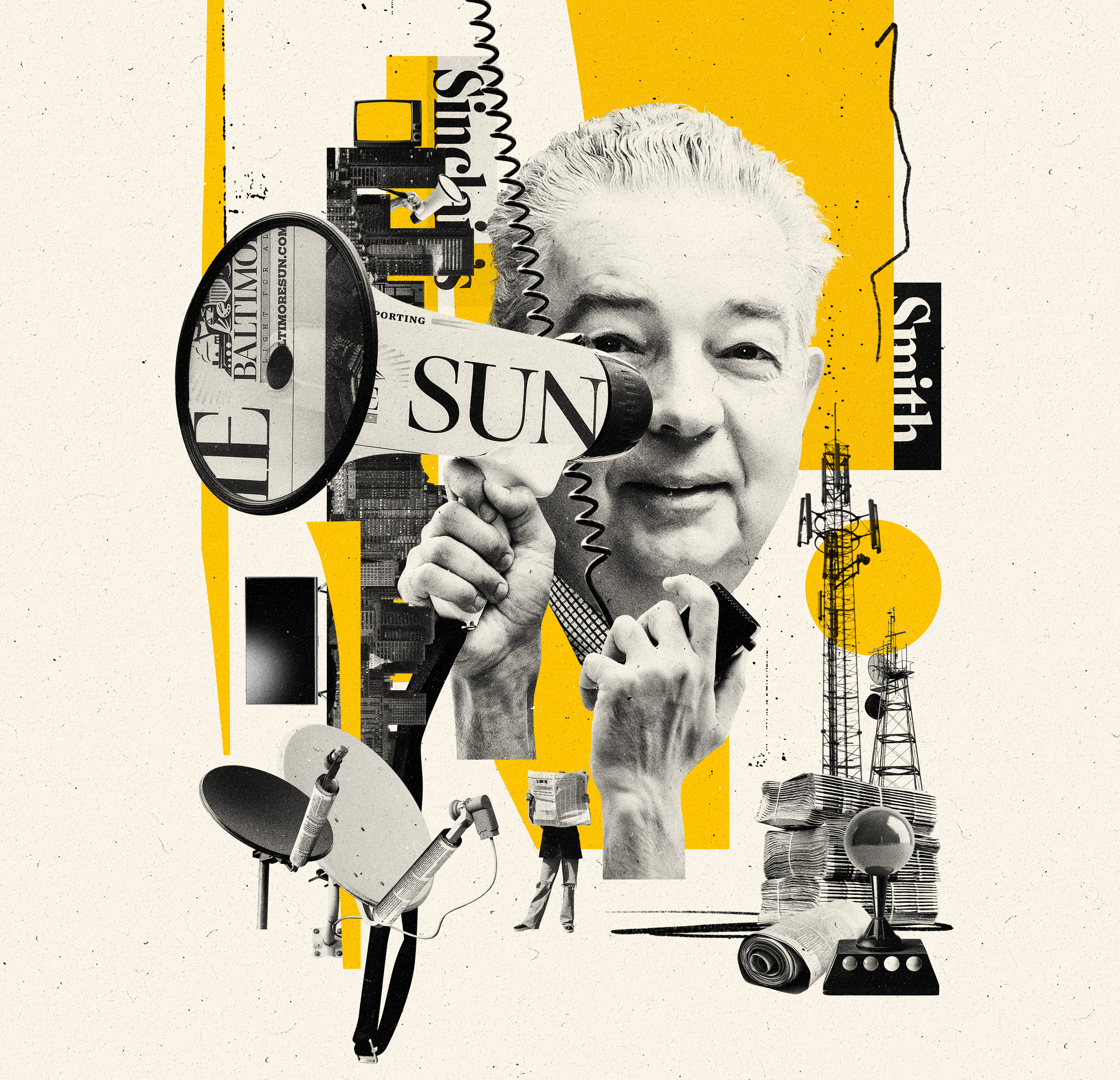

Smith, a 74-year-old, Baltimore-bred TV mogul with a long history of mixing his politics into his news operations, had promised to leave The Baltimore Sun’s journalism to its journalists. But his record sent a different message: For decades, his Sinclair Broadcast Group’s nearly 200 television stations in Baltimore and 85 other cities — one of the nation’s largest assemblages of local TV outlets — had been known for sensational, crime-saturated newscasts featuring must-run conservative commentaries and investigative stories heavy on critiques of public schools.

At first, it appeared as though the rank and file in The Sun newsroom would be left alone to cover their city: Eleven days after the Key Bridge collapse that paralyzed Baltimore’s vital waterfront in March, The Sun featured nine staff-written stories about the disaster on its homepage, including straight-ahead news stories on President Biden’s visit to Baltimore and features about underwater salvage efforts and people who’d grown fearful of crossing bridges. The news decisions were made by Sun editors on their own, without guidance or directives from the owner.

“We’re doing our thing,” a Sun reporter told me in April, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of reprisal from the new owner. “There’s been no directive to do his bidding, nothing unsavory.” When the bridge fell, “the new owners were comfortable at home in bed. We did the story. We are The Sun.”

Such bravado did not last. As the months passed, reporters, political leaders, and readers noticed increasingly troubling signs. And that reporter who’d said, “We are The Sun,” was scouting for a new job.

Inside the newsroom and around a city that had long taken pride in a paper that won a Pulitzer Prize for local reporting in 2020, disappointment, embarrassment, and outrage mounted as The Sun ran harsh right-wing opinion pieces by Smith’s co-owner, Armstrong Williams; “Ask the Vet” columns by Smith’s daughter Devon, who is a veterinarian; and an oddly boosterish Page One feature on a new restaurant opening at the Baltimore harbor front. In the 11th paragraph of that story, The Sun disclosed that the owners of the new steakhouse, Alex Smith, the CEO of Atlas Restaurant Group, and his brother, happened to be “nephews of Baltimore Sun owner David D. Smith, who is an investor in Atlas restaurants.”

Journalists who took pride in their independence and fairness worried that they were working for an operation with a personal and all-too-often political mission. After all, Smith, executive chairman of Sinclair, had reportedly told then-candidate Donald Trump in 2016 that “we are here to deliver your message. Period.” Smith’s commitment to the newspaper he bought seemed questionable; he told New York magazine a few years ago that “the print media is so left-wing as to be meaningless dribble” and that it would simply “fade away” because it has “no credibility.”

Just as in other cities where hyperwealthy Americans have bought up struggling metro newspapers with the idea that they can turn them around, Smith’s purchase of The Sun created a confusing blend of hope, suspicion, and agita in the city, across Maryland, and through much of the news business. By the time he bought The Sun — paying its hedge-fund owner more than $100 million, he has said — the paper was reduced to about 60 journalists, with no foreign bureaus, a far thinner print edition, and the same kind of sharply diminished role and audience that nearly all of America’s big-city, legacy news operations now confront.

The downturn has been steep. The Sun’s print circulation plummeted from 265,000 in 1995 to 43,000 in 2021, according to industry figures. As of last year, The Sun’s digital subscriber base was about 85,000 readers, according to an executive at another newspaper who was privy to Sun financial data.

Smith says he is saving his hometown paper from death by a thousand cuts. He wants to invest in news coverage, hire more reporters, and hold the city’s politicians to account. “I think the paper can be hugely profitable and successful and serve a greater public interest over time,” he told Sun journalists at his first meeting with them.

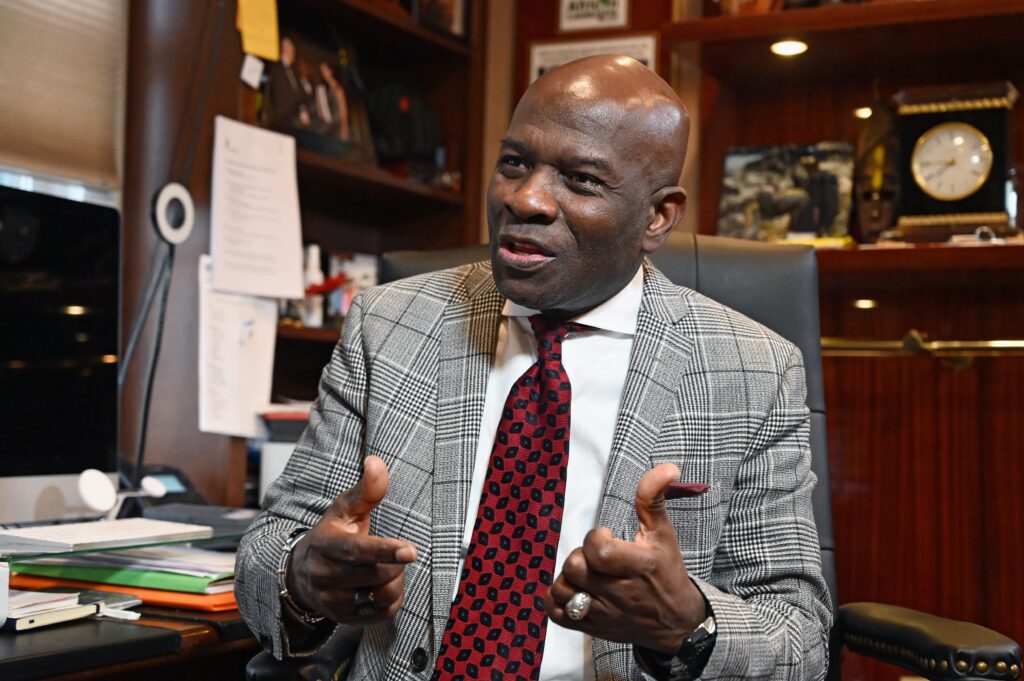

Smith did not respond to requests for an interview, just as he has refused to comment to many other news organizations since he bought The Sun. His longtime friend Williams, who owns seven TV stations he acquired from Sinclair and whom Smith brought on as minority partner in The Sun, told me in an interview that Smith’s interest in the paper stems from his passion for the city of his birth.

“Home is where his heart is,” says Williams, who lives 37 miles away in Washington, D.C., and commutes an hour each way to The Sun several days a week. “David is an entrepreneur who cares deeply about the city of Baltimore and who should run this city. He wants to tackle Baltimore’s deep-seated problems. He puts his money where his mouth is.

“He has a very difficult time separating himself as a private citizen from the things he owns,” Williams added.

That is precisely the problem, Sun reporters say. It’s the challenge faced by all the wealthy entrepreneurs around the country who have stepped in to try their hand at saving local news.

“That is the story of our time — billionaires buying big-city papers,” says Elizabeth Hansen Shapiro, chief executive of the National Trust for Local News. “It all looks like a good idea. In fact, it’s quite a challenging proposition.”

The day after he bought The Sun, Smith met with its staff at the paper’s downtown offices for more than two and a half hours. “Welcome to the new world,” he told them.

Then he added, “I haven’t read the paper in 40 years.” He said they needed to write more about crime and government dysfunction, and he wanted them to cover the city more like Baltimore-based Fox45, Sinclair’s flagship TV station.

This did not go over well. “We’re a Pulitzer Prize-winning newsroom,” a reporter pushed back. But Smith said he wanted more aggressive coverage of political corruption and the city’s troubled school system — mainstays of Fox45’s nightly story menu.

In the months since Smith’s purchase, according to current and recently departed Sun reporters, he has neither pitched specific stories directly to the newsroom nor openly critiqued The Sun’s coverage. He still maintains in meetings with Sun staffers that he doesn’t read their stories, just the occasional headline.

But after nearly a year under new ownership, The Sun is different. And Smith’s vision for the paper is driving those differences, according to Williams, who says he makes certain that The Sun reflects Smith’s ideas about fair and aggressive reporting. For a time, the world news module on The Sun’s website consisted of foreign news summaries carrying Williams’ byline — a daily aggregation of world headlines that the co-owner said he has long put together for friends. Meanwhile, in the opinion pages, Williams’ column, “The Owner’s Box,” warned against voter fraud without citing any evidence that it happens with any meaningful frequency and declared that “crime is out of control” without reporting to back up the assertion.

In September, Sun managers fired courts reporter Madeleine O’Neill, pointing to comments she’d made on the paper’s Slack messaging system criticizing the new owners for steering The Sun in a sensational direction. The Sun’s union held a rally to protest the paper’s pivot to carrying lurid crime stories produced by Fox45 and other Sinclair outlets. The Sun also published a story using the term “illegal immigrants,” in violation of AP best practices; after Sun staffers complained, the wording was changed.

Most concerning to many in the newsroom and beyond was Smith’s involvement in city politics. The owner took on a prominent role in funding a ballot initiative to shrink the city council by nearly half. Smith’s defenders noted that The Sun duly reported Smith’s contributions to a PAC promoting the downsizing of the council.

Smith has spoken in the past about using Fox45 and other TV stations in service of his political interests. Earlier this year, in his first meeting with Sun staffers, Smith explained his TV stations’ devotion to stories about corruption and inefficiency in the Baltimore school system by saying that “if I tell the story long enough and loud enough at a personal level so people can say, ‘I can relate to them, now tell me what I can do about it,’” then his audience will “go vote for people whose view is ‘I got to fix this.’”

Inside the Sun newsroom, the accumulated changes are producing a spike in anxiety. “There’s nobody at The Sun who doesn’t have résumés out,” says David Zurawik, The Sun’s former media writer and now a media studies professor at Goucher College. “What’s left of The Sun will die. Smith bought his liberal nemesis and he’s likely to do to The Sun what he’s done with his TV station. They use a tool of enlightenment and democracy the way Roger Ailes used Fox News — as a political organization masking itself as a news operation.”

Smith’s friends and critics alike agree that he urges his properties to cover local dysfunction and discord much more intensely than his competitors might — telling hard truths, his friends say, or distorting the reality on the ground, according to critics.

“Sinclair’s pattern is to paint Baltimore and urban America as dangerous hellholes,” says Craig Aaron, co-chief executive of Free Press, a nonprofit focused on halting media consolidation. Smith’s “special sauce is adding this overly partisan slant” to news coverage. “I’m a big fan of returning newspapers to local ownership, but David Smith doesn’t seem to be the way to do that.”

Smith’s father, Julian Sinclair Smith, an electrical engineer passionate about tinkering and broadcasting, ran a school for radio announcers in downtown Baltimore before launching, in 1971, WBFF (“Baltimore’s Finest Features”) on Channel 45. It ran mostly old movies and children’s shows. Julian encouraged his four boys — David, Frederick, J. Duncan, and Robert — to spend time at the downtown offices, enlisting them to keep the studios tidy.

As a young man, David Smith wasn’t much involved in the station, which eventually became known as Fox45 for its affiliation with the Fox network. After graduating high school in 1969, Smith focused on his own business dreams, becoming a partner in a company called Ciné Processors, which made 8mm copies of pornographic films. The company, based in a building owned by Smith’s father’s radio school, collapsed after a police raid resulted in the confiscation of its wares, Smith’s fellow founder told the Los Angeles Times in 2004. In the 1980s, as his father’s health declined, Smith came back to the family business, now named Sinclair, and expanded to stations in Pittsburgh and Columbus, as well as Baltimore.

At the Fox45 office, Smith and his brothers sat side by side in desks arranged in a row. Over time, Smith became first among equals, rising to chief executive of Sinclair in 1991, the same year Fox45 launched its 10 p.m. newscast, the city’s first at that hour. “I wanted to be an entrepreneur,” he told Forbes in 1996. “My father was too much of a visionary to care about profits. What I wanted was purely to make money.” On his desk, Smith kept a toy shark and a rattlesnake head.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Sinclair ballooned into one of the country’s largest owners of TV stations. Today, its portfolio of nearly 200 stations and 19 regional sports networks reaches about 40 percent of the country.

Sinclair’s influence spread beyond its directly owned stations through a controversial mechanism known as Local Marketing Agreements. The tool, originally designed to help struggling radio stations survive by combining staffs and programming with other outlets, allowed one owner to gain virtual control over two or more stations — even within a single market, despite FCC rules restricting the number of stations any one entity can own.

Sinclair became known for its sidecar deals, a maneuver in which a broadcast company gets around FCC ownership limits by having a friendly third party buy a station and then arrange for the first company to run the outlet. Smith’s mother, Carolyn Cunningham Smith, through a company of which she was majority owner, bought stations that Sinclair couldn’t. In 1997, for example, Sinclair bought one TV station in San Antonio and one in Asheville, North Carolina. That same year, Carolyn’s company, Glencairn Ltd., also bought one TV station in each of those markets. Glencairn signed over control of its stations to Sinclair through local marketing agreements, allowing Smith’s company to run two stations in each city. At the same time, Carolyn transferred her ownership interest in Glencairn to trusts in the names of her grandchildren — the children of the four Smith brothers, who owned Sinclair.

Sinclair told The New Yorker that its deals were “legally permissible operating efficiencies” undertaken “to survive in a very competitive business landscape.” But in 2001, the FCC fined Sinclair and Glencairn $40,000 each for the San Antonio and Asheville deals, which some other station owners, as well as industry watchdogs, had called anti-competitive. In 2016, when the regulator looked into Sinclair’s continued use of sidecar deals, the company agreed to pay more than $9 million to the feds, without admitting wrongdoing. Under the settlement, the FCC dropped its investigation and Sinclair kept its stations.

“What makes Sinclair’s practices disquieting,” FCC commissioner Michael J. Copps said in 2001, “are its maneuvers to acquire interests in multiple stations in seeming contravention — if not violation — of commission rules. With each transaction over the years, Sinclair has stretched the limits of the commission’s local television ownership rules.” (Years later, Copps dubbed Sinclair “probably the most dangerous company most people have never heard of.”)

“Sinclair’s pattern is to paint Baltimore and urban America as dangerous hellholes. I’m a big fan of returning newspapers to local ownership, but David Smith doesn’t seem to be the way to do that.”

— Craig Aaron, co-chief executive of Free Press

Sinclair-owned and -operated stations became known for cutting costs, boosting profits, and requiring local news operations to air “must-run” stories produced by the company’s Washington bureau and by other Sinclair stations. In 2017, the FCC fined Sinclair more than $13 million for airing more than 1,700 paid promotions for the Huntsman Cancer Institute “made to look like independently generated news coverage,” the commission concluded.

At Fox45, at least in the early years, journalists “could cover whatever we wanted,” says Jeff Barnd, who spent many years as the station’s chief news anchor. Fred Smith sent Barnd to the Amazon to produce a Fox45 series about the devastating environmental impact of clear-cutting tropical forests, a story that was inspired by Al Gore’s “Inconvenient Truth” presentation about climate change and that cut against the owners’ politics.

But as Sinclair expanded, David Smith began to press producers and reporters to do his bidding on-air, according to several former employees.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Sinclair required its anchors around the country to recite company-provided editorials supporting the Bush administration’s “war on terror.” And in 2004, Barnd hosted a Sinclair primetime program boosting claims by an anti-John Kerry group, Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, that the Democratic presidential candidate’s congressional testimony during the Vietnam War about American atrocities had led to the torture of U.S. prisoners of war. The claims made by the group were largely discredited, and Sinclair’s own Washington bureau chief, Jon Leiberman, called them “biased political propaganda” designed to sway the 2004 election. Sinclair fired Leiberman and sued him for damages. Leiberman, who declined to comment for this article, and Sinclair settled out of court; the deal prohibited Leiberman from speaking about Sinclair.

At Sinclair stations around the country, news anchors were handed “must-run” scripts of conservative editorials from headquarters in Maryland that they were required to read out on their newscasts. Outrage over the practice went viral in 2018 when a video produced by Deadspin showed dozens of anchors at Sinclair stations around the country all reading the same “must-run” script, which lamented “the troubling trend of irresponsible, one-sided news stories plaguing our country” and took the news media to task for pushing “their own personal bias and agenda to control ‘exactly what people think.’”

Back in Hunt Valley, Maryland, Sinclair’s home base, an executive ordered Barnd to do a story in 2015 about claims by a retired military officer that Sharia law was being enforced in several U.S. cities. “This comes from the owner,” Barnd says he was told. He interviewed the officer, who named several cities, but when Barnd checked out the claims, he found them to be groundless. “I think I have a non-story,” Barnd recalls telling his bosses. “I reported back to Hunt Valley, and I was told in no uncertain terms, ‘The story’s running anyway.’” (Sinclair did not respond to a request for comment on this article.)

Barnd’s friends urged him to quit, but that wasn’t so easy. Sinclair’s contracts were constructed to require newscasters who left before their term of employment expired to reimburse the company for a portion of their salary. That stopped or delayed some journalists from leaving.

More and more, Smith’s personal politics elbowed their way into the assignments handed to Fox45 reporters, several station veterans say. “Early on, 95 percent of the stories were non-political,” recalls Stephen Janis, a former Fox45 producer. “But then I got a bunch of assignments to do gun rights stories. Then came the incident where we accused a local activist of advocating for killing cops.”

In 2014, Fox45 reported that the activist, Tawanda Jones, led protesters in a chant of “We won’t stop. We can’t stop, so kill a cop.” But the chant was actually “We won’t stop. We can’t stop till killer cops are in cellblocks.” Jones complained to the station, which took the story down from its website and handed Barnd a script to read on the air.

“Although last night’s report reflected an honest misunderstanding of what the protesters were saying, we apologize for the error,” the statement read.

The apology wasn’t enough for some Fox45 journalists.

“I got a little scared, to be honest,” Janis says. “I had to move on.”

Smith has always argued that he keeps his views separate from his companies’ journalism, but his political donations paint a portrait of a hard-right activist who supports causes and groups often antagonistic to news organizations.

Through his family foundation, Smith has given six-figure donations to right-wing groups such as Project Veritas, which specializes in caught-on-video exposés of journalists and political figures at bars taking left-wing positions or saying dumb things; Turning Point USA, which advocates for conservative causes on college and school campuses; and Moms for Liberty, which pushes to purge school curricula of materials about gay rights, critical race theory, and gender issues.

Smith’s politics are misunderstood, Williams contends, arguing that Smith is neither a conservative nor a Republican, but rather a libertarian who regularly supports candidates from both parties. Indeed, Smith has donated through the years to Democrats such as New York Sen. Chuck Schumer, Maryland Sens. Barbara Mikulski and Chris Van Hollen, and the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee. But he’s given more often to Republicans, in Maryland and nationally, donating to candidates such as John McCain, Kevin McCarthy, and Tim Scott, and the National Republican Congressional Committee. Federal elections records show no donations to Trump’s campaigns or related organizations.

Yet Trump made no secret of his admiration for Sinclair, tweeting in 2018 that it was “so funny to watch Fake News Networks, among the most dishonest groups of people I have ever dealt with, criticize Sinclair Broadcasting for being biased. Sinclair is far superior to CNN and even more Fake NBC, which is a total joke.”

Trump’s tweet in support of Sinclair did not come in a vacuum. The bond between the president and Smith’s company traces back to 2016, when Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law, told business executives in New York that the Trump campaign had made a deal with Sinclair to give its stations more access to the candidate. As reported by Politico, Kushner said Sinclair agreed in exchange to air Trump interviews without adding commentary. Sinclair stations aired 15 exclusive interviews with Trump and 10 with his running mate, Mike Pence, The Washington Post reported. (Sinclair said its offer of interviews to Hillary Clinton and other Democrats were declined; the Clinton campaign said at the time that it was wary of accepting because of Sinclair’s slanted coverage, but Virginia Sen. Tim Kaine, her running mate, did appear on Sinclair stations a few times.)

The ties between Trump and Sinclair quickly tightened. The day before Trump was inaugurated, Smith, Williams, and Sinclair’s chief executive, Christopher Ripley, met with Ajit Pai, who was about to become Trump’s FCC chairman. Within days of taking office, Pai announced changes that made it easier for Sinclair to buy more TV stations. Soon after, Sinclair announced its plan to merge with Tribune Media, one of the country’s biggest owners of TV stations.

To obey FCC limits on ownership of TV stations, Sinclair proposed selling some of its stations, but the plan was to sell some of them to the Sinclair-connected company controlled by Smith’s mother’s estate. “It’s striking that all of our media policy decisions seem almost custom-built for this one company,” Jessica Rosenworcel, the only Democrat on the FCC, told The New Yorker in 2018 as the deal moved toward approval. “Something is wrong.”

The Sinclair-Tribune merger proved to be too much for the FCC to stomach. After protests from media diversity advocates and members of Congress — and opposition from some of Trump’s other media allies, Sinclair competitors such as Fox News and Newsmax — Pai announced that Sinclair’s plan to sell the stations but maintain control of them would likely be “in violation of the law.”

Two years later, the FCC slammed Sinclair with the largest fine in the agency’s history, a $48 million penalty for deceiving the government when the company sold off some of its stations to companies that had close ties to the Smith family.

Despite the failure of the Tribune merger, Sinclair benefited from other FCC moves during the Trump years, such as the elimination of a rule that required TV stations to keep a studio in the market they served. That change allowed Sinclair to reduce staffing and even shut down newsrooms in several cities, including in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the nation’s 63rd-largest market, according to Nielsen. Sinclair’s station there, ABC affiliate KTUL, produced its last local newscast on Dec. 8, 2023, and lost most of its employees. Since then, the station’s news shows have come mainly from Sinclair’s station 100 miles away in Oklahoma City. Sinclair explained the change in a statement, noting that the Tulsa newscast would henceforth come from a “regional content center to super-serve the Tulsa and Oklahoma City markets.”

Viewers noticed, says Mark Bradshaw, a former KTUL anchor who was laid off. “I can’t go anywhere without people telling me how angry they are about what happened,” the former anchor says. “They say, ‘I’m not interested in car crashes or house fires 90 miles away.’”

Inside the Sun newsroom, the anxiety over Smith’s politics and plans for the paper is constant. Although Smith held meetings with each desk last spring, “all he tells us is that our purpose is to make him money,” says one Sun reporter who attended such a meeting.

Williams confirms that turning a profit is Smith’s supreme aim. “If you’re not making money, you’re not going to have a news organization,” he says. “People say we’re ideological, we have an agenda. They don’t see that we’re saving print. We’re saving jobs.”

Williams met Smith at the 1999 White House Correspondents Dinner in Washington, where they were introduced as fellow conservatives by Wesley Pruden, then editor of the Unification Church-owned Washington Times. Shortly after that meeting, Williams was hired to deliver commentaries on Sinclair stations, which he did until Smith fired him in 2005, soon after the FCC fined Sinclair $36,000 for airing Williams’ segments praising the Bush administration’s education reforms — without informing viewers that the government had paid Williams $240,000 to promote its policies.

Williams says he now spends most of his time at The Sun. “I’m running the paper every day,” he tells me. The Sun’s masthead lists Smith and Williams first, as “principals.” But much of the paper’s editorial leadership remains unchanged, under publisher and editor-in-chief Trif Alatzas, who assumed that role in 2016 and has been at The Sun for more than two decades. Alatzas did not respond to requests for comment.

Williams says the primary changes he and Smith have made have been to emphasize print over digital, reduce the use of wire copy, focus on Maryland, and invest in covering topics such as public safety and education.

“If you’re not making money, you’re not going to have a news organization. People say we’re ideological, we have an agenda. They don’t see that we’re saving print. We’re saving jobs.”

— Armstrong Williams, commentator, entrepreneur, and co-owner of The Baltimore Sun

Contrary to the strategies of nearly every other newspaper, Smith and Williams want to “use The Sun as a model to show the United States that the way to save daily newspapers is the print model,” Williams says. “You can do a TV story in 15 minutes, but with print, it’s long, it’s investigative. It’s a much higher bar to publish than anything on broadcast. The print — you can hold onto and save and study it. It’s far more engaging and far more credible than anything else. You can’t post TV stories on the fridge.”

These days, Williams, whose role spans the news and opinion sides of The Sun, says he and Smith go through the paper each morning, contradicting Smith’s assertion that he doesn’t read the paper. “He’ll say to me, ‘You might want to do more of this,’ … and I’ll say to Trif … , ‘Can we look at doing more of this?’”

“This” sometimes means more stories on crime or the school system, but Williams says it does not include any political slant. “We’re referees,” he says. “David and I believe in neutralism.”

The Sun has hired some reporters, but newsroom staffers remain troubled by Smith’s political activism in the city they are charged with covering. In 2022, Smith bankrolled a ballot initiative to limit the terms of city council members, to the tune of more than $500,000. The measure passed overwhelmingly. Fox45 covered the story, but without referring to Smith’s donations to the campaign, according to two Fox45 newsroom employees at the time. (Fox45 referred me to Sinclair for comment on this article, but Sinclair did not respond.)

Smith staked a claim in Baltimore’s mayoral race before buying The Sun. He gave $200,000 to a PAC supporting former Mayor Sheila Dixon’s Democratic primary challenge against Mayor Brandon Scott. Smith’s adult children also gave the maximum permissible donations to Dixon, who resigned from office in 2010 after Sun reporting helped lead to criminal charges and her conviction for embezzling gift cards donated for low-income families.

Ahead of this year’s primary, the Baltimore Brew reported, the Sinclair chairman struck a deal with Dixon: He would raise money for her campaign, and she in turn would support key aspects of Smith’s plan for Baltimore — including getting rid of the city’s school superintendent and scrapping Scott’s signature crime-fighting program, which Fox45 has consistently criticized. Dixon denied having any relationship with Smith and that she had offered political favors in exchange for campaign contributions. Scott beat Dixon handily. (The Sun made no official endorsement in the race. “I knew there’d be talk about favoritism,” Williams explained. “So I said, ‘You know what? Let’s not endorse candidates at all.’”)

Smith also funded a civic group campaigning for the ballot initiative to slash the city council from 14 members to eight. Smith said he funded the initiative to reduce government waste, but the city’s charter review commission called the initiative a “blatant attempt” to influence Baltimore’s government. “It would allow someone like David Smith to have even more influence over the political worldview and perspectives that are represented on the council,” charter commission member Dayvon Love told The Baltimore Banner. Baltimore voters resoundingly rejected the initiative in November.

Between Smith’s political activities and The Sun’s increasing use of Fox45 stories — including crime and fire news and unscientific polls with leading questions — journalists in The Sun’s newsroom have started to push back. In August, the newsroom’s union denounced the use of Sinclair and Fox45 material. “These stories often lack nuance, context or opposing views,” The Sun Guild wrote. After a meeting that the union requested with management, Sun stories originating from Fox45 are now labeled as such. But the stories continue to run.

Williams replied to the union, saying that “I deeply respect the opinions of the Baltimore Sun Guild. I do not impugn their motives. … I assume the Guild reciprocally appreciates legitimate managerial prerogatives in the journalistic enterprise. Constructive criticism is always welcome even if ultimately found unpersuasive.”

In the newsroom, where Sun journalists are working under an expired contract and without having received an across-the-board raise for more than a decade, the Guild’s unit chair, reporter Christine Condon, accused Smith in a statement of seeking “to leave us defenseless, so that they can change the Sun however they please.”

“It definitely has been frustrating to see some people say this is the end of The Sun,” another Sun reporter says. “But we’re not easily discouraged. We have leverage: If you start seeing us pulling our bylines from stories, you’ll know we’re resisting something bad.”

Five days before election day on Nov. 5, the Guild announced a weeklong byline strike.