|

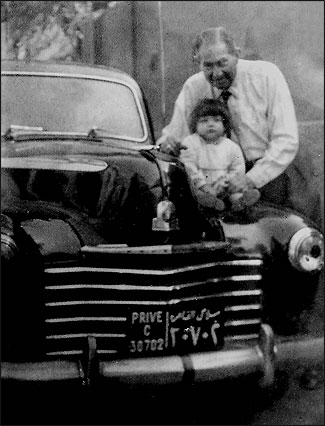

| Lucette Lagnado, whose family called her Loulou, with her father. Photo courtesy of Lagnado family archives. |

I took a leave from The Wall Street Journal to work on two family memoirs, but in a way I never left—and the pesky habits, methods, techniques, even the mindset I'd always adopted as an investigative reporter stayed with me. For better and for worse.

My work had made me a stickler for accuracy and precision, with a fear bordering on phobia of making a mistake. Practically speaking, I knew as did my editors that my stories were likely to be read over carefully, with the people I exposed poised to attack, so that I had to be excruciatingly careful. I mastered habits peculiar to the culture of investigative reporting such as "bulletproofing"—as in, 'you have to bulletproof your story,' to make sure no one could poke holes in it.

Deadlines were invariably terrifying events, when I walked around the newsroom with a copy of my 2,000-word story, reading it over and over again, afraid I'd gotten so much as a comma wrong. Then, suddenly, here I was with a contract to write a 100,000-word book about my Egyptian-Jewish father who had passed away years earlier, so that I couldn't even turn to him to verify facts and run by rumors.

I secretly dubbed my book, "100 Years of Levantine Solitude." And that was in fact my grand ambition—to chronicle what happened to my family over the course of a century, beginning with my father's arrival in Cairo from his native Syria as an infant in 1901 to his courtship of my mother in 1940's Cairo, from my family's forced exile to America all the way to my parents' passing in the 1990's. I was going to document the rise and fall of my family through these decades and, in the process, recreate this vanished world that had haunted me so—a time when and a place where Jews lived peaceably with Muslims and Christians in a magical Arab city called Cairo.

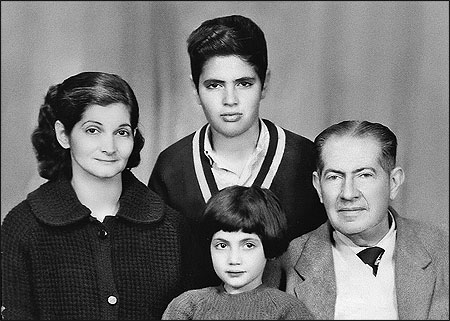

Before leaving Egypt, Leon and Edith had this portrait taken with their 6-year-old daughter Loulou and her brother Isaac. Photo courtesy of César Lagnado, Lagnado family archives.

Digging for Details

I was sure that all those great habits cultivated as a journalist would help me with my undertaking, and at first they did. I set about my book with the same fervor and diligence that I'd approach my Page One lead stories. I made frantic phone calls and contacted sources around the world and pored through old documents I retrieved by filing the equivalent of Freedom of Information Act requests. Even before formally working on my book, I'd approached the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) that had resettled us and requested our family files. It took a while but to my amazement, the agency found them—scores of letters documenting our sad efforts to find a home after leaving Egypt. There, in the midst of the thick dossier, was the single most compelling document I'd find about my family: The ledger showing my dad's payments in $10 and $15 increments for our passage to America on the Queen Mary.

In approaching this project as a journalist, I thought, why not try for other immigration files? I recalled that another agency called the New York Association for New Americans (NYANA), now defunct, had helped in our resettlement, so I demanded our files from there as well. These proved to be even more jarring—especially the pages of case notes from our old social worker, railing against my dad for being too old-fashioned, too sexist and patriarchal. Between the HIAS and the NYANA papers, I felt I had a sound basis for reconstructing our early days getting out of Egypt and of our emigration to America. Emboldened by the results of my quest, I flew to Paris and retrieved my family dossier from our time as refugees living in a fleabag hotel for nearly a year in the 1960's.

With aspects of our lives that documents didn't cover, I searched for sources,

exactly as I would with a story. For chapters on my father as a single man in 1940's Cairo, I flew to Milan and huddled with an elderly cousin who had lived with him before his marriage to my Mom. He vividly remembered watching as my Dad (before he was my dad) went out night after night, not returning till the early dawn. My cousin left it to my imagination to figure out where "the man in the white sharkskin suit"—a description of him that I made the title of my first book—went every night. (Think: Women, bars, casinos, cabarets—the typical Cairo nightlife, once upon a time.) But he also stressed that Dad was always back by dawn—a stickler about attending morning services at the local synagogue, no matter what his nocturnal adventures had been.

I searched for any other relatives or friends who knew my father. Most of them were in their 80's, even their 90's, and that was great, because to my mind the older they were, the greater the chance they would have significant remembrances—assuming their own memory was still intact.

I perfected the art of reported memory. When my own memory failed me, I turned to family members and my older siblings with questions about family incidents. Once again my years as a reporter came to my aid. Indeed, I was so relentless in the way I questioned my older sister that she seemed to dread our encounters and would say to me, exactly as a reluctant source would have, "Are you through now?" My oldest brother was a bit more lenient. An accountant by profession, he had a special interest in documenting the past. I found that over the years he had kept an extraordinary array of Dad's papers—cancelled checks going back to the 1980's, business cards from Cairo in the 1950's.

Occasionally it occurred to me to wonder why he had preserved so much. Was he expecting an audit of our father's life? Was that, in effect, what I was doing?

Ultimately, no matter what I did, there were still gaps—areas where reporting basically no longer worked, where I had reached the limits of its usefulness. Even with my trove of documents, my ability to find good sources and persuade them to cooperate, I was missing pieces of the story. Key relatives had died or there remained no written record of what I was seeking. What to do?

Letting Memories Flow

I guess that is when I was forced to learn my new craft—as I transitioned from journalist to memoirist. I had heard, for example, that my father had a dalliance with a legendary Egyptian singer named Om Kalsoum, possibly the greatest Egyptian performer, idolized in the Middle East. It was such a tantalizing story but how to confirm? Om Kalsoum was long dead, and in terms of the people around her, who on earth could have confirmed that once upon a time an imam's daughter turned chanteuse had a relationship with a tall handsome Jewish man about town who favored white sharkskin suits?

As I weighed what to do, I realized the story was consistent with other stories I'd heard about Dad and rang true. But I owed it to the reader to state explicitly that it was still in the realm of mythology, albeit a myth I happened to believe.

This section remains one of my favorites. I had begun exploring it using traditional reporting, contacting people in Egypt, finding long-lost relatives who might have known about my father and Om Kalsoum. I couldn't really confirm it but rather than adhere to the journalistic law of "if in doubt leave it out," I decided that the mere fact such a story could have circulated about my dad revealed worlds about his character and reputation.

The greatest impediment of all to these memoirs turned out to be me—my own memory, the memory of someone who had left Egypt as a small child. At the tender age of 6, I had become a refugee and undertaken a journey most adults would find daunting, from Egypt to France to America. My memories of that period were nothing like those of my siblings; they were a little girl's memories, marked by the longings of a child who suddenly finds herself having lost all that she treasures—her school, her home, her street, her cat, her favorite patisserie where her dad takes her as a treat each afternoon.

They were hardly enough to turn into a memoir of a lost Egypt, and I was at a loss as to what to do until I remembered a cardinal rule I'd learned at the Journal—what we dubbed "jiu jitsu." That was the art of turning a weakness into strength, to transform even a flaw in a story into an asset. That is when I realized that I had to tell the story—this seemingly adult memoir of exile and loss—in the voice and through the eyes of a child, of the little girl me, a girl named Loulou, who watches bewildered as her world changes because of massive political and social altercations. Loulou doesn't understand the politics—she has no sense that a revolution has taken place in Egypt and that the country is now under a military dictatorship that doesn't want Jews or foreigners. But she does feel—intensely—the events around her. She simply experiences them under her terms.

Suddenly my undertaking made perfect sense. No, I wouldn't be able to write a memoir about the fall of King Farouk and the rise of Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser, but I would be able to tell the story of an elegant Swiss patisserie named Groppi's where I—or young Loulou, rather—loved to go and sit in a pebbled garden and spoon out freshly-made chantilly crème. I would be able to recall once upon a time attending a French lycée in the heart of Cairo and wearing a dashing uniform with a crest. I would conjure up my home, and my little cat Pouspous who I loved above all others, and turn her into a major character. And of course I would write about my home, but in the way that I had known it—as large and graceful, with balconies facing both a boulevard and an alleyway, and the constant vendors stopped by selling marvelous treats: fresh figs, apricots, fish, and occasionally, baskets of rose petals my Mom used to make rose petal jam.

The memories flowed, as did the emotions, and if I needed to "fact check," well, I would turn to an older sibling and run some incident by them.

I have come to realize that my obsessive precision—a great virtue in a reporter—wasn't necessarily the greatest quality in a would-be memoirist. Imagination, the ability to recall and bring to life lost people and lost worlds, are far more valuable. Yet I suppose that my reporter's mindset ultimately served me well. I took less poetic license, I believe, than some of my fellow memoirists and became a true believer in the power and potential of reported memory.

Lucette Lagnado is the author of two memoirs about her Egyptian-Jewish family, "The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit: A Jewish Family's Exodus From Old Cairo to the New World," published by Ecco in 2007, and more recently, with the same publisher, "The Arrogant Years: One Girl's Search for Her Lost Youth, From Cairo to Brooklyn." She is a reporter at The Wall Street Journal.