If editions of the Sun Herald, produced in the first few days after Katrina ravaged our town of Biloxi and the entire Mississippi coastline, are the first draft of this storm's history, then the book we published, "Katrina: 8 Hours That Changed the Mississippi Coast Forever," can be considered our family album. On its pages, reporters and photographers document what "home" was like here before and after nature's extraordinary force altered our lives so dramatically on August 29, 2005.

The first accurate description we heard of the storm's wrath was told to a Sun Herald reporter in four words: "Your city is gone." Indeed all of our coastal cities: Waveland, Bay St. Louis, Pass Christian, Long Beach, Gulfport, Biloxi, Ocean Springs, Moss Point, Pascagoula — and inland communities, too — were blown and washed away on that dreadful day. The words used to tell this story are the faithful testimony of Katrina's victims but, because this is more album than memoir, its photographs tell the stories we will forever remember. For many of us, some of its pages will no doubt become tear-stained as survivors turn them to reveal images of their lost cities and transformed lives.

But this book is not only a story of tragedy and devastation. It is one of survival, helping hands, hope and even triumph, too. It might seem a cliché these months later, but from our vantage point on the frontlines of this disaster, the strength of Mississippians was a righteous truth that bolstered the journalists who told their stories, as it did the thousands of volunteers and workers who helped them dig out in those early days and then stayed to do so many good deeds. In any book about Katrina, no final chapter can yet be written. There is only the latest chapter, and for the Sun Herald the focus has turned to the spirit of a people beginning the recovery of their region in a highly organized, deliberate and democratic fashion.

The Sun Herald's Katrina book tells one of the more important stories in American history, and its words and images are brought to its pages by journalists in South Mississippi who have not only experienced Katrina but continue to cover the stories of its aftermath.

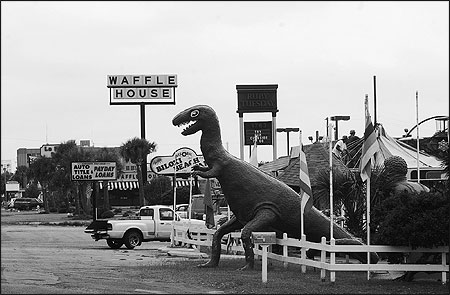

Biloxi Beach Park on U.S. 90 was an attraction for coast residents and tourists for decades. Hurricane Katrina obliterated the popular amusement park. Photos by John C. Fitzhugh/Courtesy of the Sun Herald.

Katrina Arrives

It can sometimes be hard to remember what Biloxi was like before Katrina arrived. But we can look back at the Sun Herald's last pre-storm edition and see that as Hurricane Katrina bore down on the Gulf Coast, our front-page headline asked the question, "Another Camille?" and a Page One editorial prophetically predicted that this hurricane would alter our communities and our lives forever.

After this edition went out, two Sun Herald reporters, one in the Harrison County Emergency Operations Center in Gulfport and the other from a home in Hattiesburg, continued to communicate with readers through blogs. They passed along information that was unfolding by the hour that was read by those who stayed to face Katrina and those who evacuated to distant points. We'd already sent a team of editors from our newsroom in Biloxi to the Ledger-Enquirer in Columbus, Georgia, in anticipation that they might need to produce the Sun Herald for an unspecified period of time from that newsroom.

Soon we knew the answer to our headline's question: Katrina's destruction was many times worse than that of Camille. It would have been hard to imagine a worse scenario for the South Mississippi coast, as Katrina's 30-mile-wide eye-wall came ashore over Waveland and Bay St. Louis, and her deadly northeast quadrant pounded every inch of the state's coast. Katrina's force produced the world's highest recorded storm surge — some 35-feet in Pass Christian — far eclipsing the 23-foot mark of Camille in 1969.

When the worst of the storm had passed, Sun Herald news staff began to report the awesome scenes of death and destruction that Katrina had wrought along 70 miles of Mississippi's coast where homes, businesses, roads and bridges were destroyed, many of them flattened beyond recognition, and electric service, cell towers, phone lines were all gone.

Even though the unimaginable had happened, the Sun Herald, which had not missed publishing an edition in its 121-year history, did not break that string. On Tuesday morning, August 30th, we produced an eight-page newspaper in Columbus that was trucked into Biloxi and distributed across the region by reporters, photographers, editors and other employees who drove copies to emergency shelters and to people wherever they could be found. The first edition had a press run of 20,000; during the next few days this was increased to 80,000.

For the first month after Katrina, we delivered newspapers free of charge. Publishing and delivering the paper was accomplished under the most trying circumstances for Sun Herald staff, many of whom had lost their homes. In this very chaotic environment — in which more than 70 percent of coastal homes were destroyed or severely damaged — the newspaper continued to make extraordinary efforts to see that the news reached readers. In addition to the initial loss of tens of thousands of home delivery customers, more than half of our news boxes were destroyed and half of our circulation force was displaced. Some paper routes were almost completely obliterated, and many subscribers were relocated to tents or FEMA trailers. By year's end we were still delivering free papers to thousands, and some carriers were experiencing some of the worst circumstances; to deliver the paper, some of them had to walk over piles of debris.

For those privileged to get them into the hands of readers, seeing people's eager anticipation for the Sun Herald was gratifying. For many people, this newspaper was their primary source of news, and the Sun Herald was soon transformed into something resembling the town square for South Mississippians whose communities no longer existed. When things were so desperate in those early days, the newspaper's editorial voice spoke loudly to the world of our plight and let it be known when government assistance programs were failing. Soon after Katrina swept so much away, our newspaper's front-page headline declared, "Help us Now," and a Page One editorial spoke clearly of our needs: "We are not calling on the nation and the state to make life more comfortable in South Mississippi," our editorial said, "We are calling on the nation and the state to make life here possible." It became very clear to us at the newspaper, and I believe to the community, that during this incredible period of universal suffering there was no "us and them" nor an "editorial we;" there was just "we."

What we reported was also available on our Web site, for those who had access to the Internet. News could be found there, but also the site became the posting place for useful bulletin board information that was necessary for life in the post-Katrina world.

As important as it is to get the paper to our readers, it is the incredible news coverage of Katrina's impact on South Mississippi that has been at the center of the Sun Herald's effort. Since the storm, our news staff of 50 has produced more than 2,800 news stories on our towns and the people whose heroic response has humbled us and yet made us so proud to be able to tell their story. As the staff of the Sun Herald has worked tirelessly to meet their obligations, each of us has been reminded of how very important a newspaper is to a community. Our coverage of Katrina provided a sense of fulfillment and reminded us of journalism's true purpose.

Stan Tiner, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is executive editor and vice president of the Sun Herald in Biloxi, Mississippi.

The first accurate description we heard of the storm's wrath was told to a Sun Herald reporter in four words: "Your city is gone." Indeed all of our coastal cities: Waveland, Bay St. Louis, Pass Christian, Long Beach, Gulfport, Biloxi, Ocean Springs, Moss Point, Pascagoula — and inland communities, too — were blown and washed away on that dreadful day. The words used to tell this story are the faithful testimony of Katrina's victims but, because this is more album than memoir, its photographs tell the stories we will forever remember. For many of us, some of its pages will no doubt become tear-stained as survivors turn them to reveal images of their lost cities and transformed lives.

But this book is not only a story of tragedy and devastation. It is one of survival, helping hands, hope and even triumph, too. It might seem a cliché these months later, but from our vantage point on the frontlines of this disaster, the strength of Mississippians was a righteous truth that bolstered the journalists who told their stories, as it did the thousands of volunteers and workers who helped them dig out in those early days and then stayed to do so many good deeds. In any book about Katrina, no final chapter can yet be written. There is only the latest chapter, and for the Sun Herald the focus has turned to the spirit of a people beginning the recovery of their region in a highly organized, deliberate and democratic fashion.

The Sun Herald's Katrina book tells one of the more important stories in American history, and its words and images are brought to its pages by journalists in South Mississippi who have not only experienced Katrina but continue to cover the stories of its aftermath.

Biloxi Beach Park on U.S. 90 was an attraction for coast residents and tourists for decades. Hurricane Katrina obliterated the popular amusement park. Photos by John C. Fitzhugh/Courtesy of the Sun Herald.

Katrina Arrives

It can sometimes be hard to remember what Biloxi was like before Katrina arrived. But we can look back at the Sun Herald's last pre-storm edition and see that as Hurricane Katrina bore down on the Gulf Coast, our front-page headline asked the question, "Another Camille?" and a Page One editorial prophetically predicted that this hurricane would alter our communities and our lives forever.

After this edition went out, two Sun Herald reporters, one in the Harrison County Emergency Operations Center in Gulfport and the other from a home in Hattiesburg, continued to communicate with readers through blogs. They passed along information that was unfolding by the hour that was read by those who stayed to face Katrina and those who evacuated to distant points. We'd already sent a team of editors from our newsroom in Biloxi to the Ledger-Enquirer in Columbus, Georgia, in anticipation that they might need to produce the Sun Herald for an unspecified period of time from that newsroom.

Soon we knew the answer to our headline's question: Katrina's destruction was many times worse than that of Camille. It would have been hard to imagine a worse scenario for the South Mississippi coast, as Katrina's 30-mile-wide eye-wall came ashore over Waveland and Bay St. Louis, and her deadly northeast quadrant pounded every inch of the state's coast. Katrina's force produced the world's highest recorded storm surge — some 35-feet in Pass Christian — far eclipsing the 23-foot mark of Camille in 1969.

When the worst of the storm had passed, Sun Herald news staff began to report the awesome scenes of death and destruction that Katrina had wrought along 70 miles of Mississippi's coast where homes, businesses, roads and bridges were destroyed, many of them flattened beyond recognition, and electric service, cell towers, phone lines were all gone.

Even though the unimaginable had happened, the Sun Herald, which had not missed publishing an edition in its 121-year history, did not break that string. On Tuesday morning, August 30th, we produced an eight-page newspaper in Columbus that was trucked into Biloxi and distributed across the region by reporters, photographers, editors and other employees who drove copies to emergency shelters and to people wherever they could be found. The first edition had a press run of 20,000; during the next few days this was increased to 80,000.

For the first month after Katrina, we delivered newspapers free of charge. Publishing and delivering the paper was accomplished under the most trying circumstances for Sun Herald staff, many of whom had lost their homes. In this very chaotic environment — in which more than 70 percent of coastal homes were destroyed or severely damaged — the newspaper continued to make extraordinary efforts to see that the news reached readers. In addition to the initial loss of tens of thousands of home delivery customers, more than half of our news boxes were destroyed and half of our circulation force was displaced. Some paper routes were almost completely obliterated, and many subscribers were relocated to tents or FEMA trailers. By year's end we were still delivering free papers to thousands, and some carriers were experiencing some of the worst circumstances; to deliver the paper, some of them had to walk over piles of debris.

For those privileged to get them into the hands of readers, seeing people's eager anticipation for the Sun Herald was gratifying. For many people, this newspaper was their primary source of news, and the Sun Herald was soon transformed into something resembling the town square for South Mississippians whose communities no longer existed. When things were so desperate in those early days, the newspaper's editorial voice spoke loudly to the world of our plight and let it be known when government assistance programs were failing. Soon after Katrina swept so much away, our newspaper's front-page headline declared, "Help us Now," and a Page One editorial spoke clearly of our needs: "We are not calling on the nation and the state to make life more comfortable in South Mississippi," our editorial said, "We are calling on the nation and the state to make life here possible." It became very clear to us at the newspaper, and I believe to the community, that during this incredible period of universal suffering there was no "us and them" nor an "editorial we;" there was just "we."

What we reported was also available on our Web site, for those who had access to the Internet. News could be found there, but also the site became the posting place for useful bulletin board information that was necessary for life in the post-Katrina world.

As important as it is to get the paper to our readers, it is the incredible news coverage of Katrina's impact on South Mississippi that has been at the center of the Sun Herald's effort. Since the storm, our news staff of 50 has produced more than 2,800 news stories on our towns and the people whose heroic response has humbled us and yet made us so proud to be able to tell their story. As the staff of the Sun Herald has worked tirelessly to meet their obligations, each of us has been reminded of how very important a newspaper is to a community. Our coverage of Katrina provided a sense of fulfillment and reminded us of journalism's true purpose.

Stan Tiner, a 1986 Nieman Fellow, is executive editor and vice president of the Sun Herald in Biloxi, Mississippi.