Scott Stossel, editor of The Atlantic, has reason to be nervous. That’s partly because of his personality—detailed in “My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread, and the Search for Peace of Mind” published earlier this year—but also because the venerable print magazine over which he presides is just barely in the black. Stossel, who describes himself as “platform agnostic,” is on his second tour of duty with The Atlantic. After joining the staff in 1992, he helped launch The Atlantic Online, the title’s initial digital venture. He worked at the American Prospect from 1996 to 2002, when he returned to The Atlantic.

The Atlantic recently decided that The Wire would be reintegrated into its main website

Founded in Boston as The Atlantic Monthly in 1857 and now based in Washington, D.C., the magazine is successful both online and in print. While print circulation has grown to nearly 500,000, the number of unique monthly visitors to TheAtlantic.com hit a high of 16 million this spring. Parent company Atlantic Media has launched two successful spinoffs, CityLab (formerly The Atlantic Cities) and The Wire (formerly The Atlantic Wire). Stossel spoke with Rachel Emma Silverman, a 2014 Nieman Fellow, during a visit to Lippmann House earlier this year.

A lightly-edited transcript follows:

Rachel Emma Silverman: Thanks everybody for coming. I was going to introduce myself, but I think you all probably know me. So, I will introduce our guest. I’m pleased to introduce Scott Stossel, editor of The Atlantic, the venerable 157-year-old publication founded way back in 1857. Stossel has been at The Atlantic for more than a decade and before that was the executive editor of The American Prospect magazine. In addition to being a Harvard graduate, Stossel is also the author of two books: “Sarge,” which is a biography of Sargent Shriver, who helped found the Peace Corps and, more recently, “My Age of Anxiety: Fear, Hope, Dread, and the Search for Peace of Mind,” which came out in the beginning of the year.

In “My Age of Anxiety,” which is part family memoir and part history of science, Stossel vividly describes his own experiences with severe anxiety, a condition that affects some 40 million American adults (about 1 in 6 people). In a passage from the book, Stossel describes some of his intense phobias. In addition to public speaking, he says he suffers, and I quote, from “fear of enclosed spaces (claustrophobia), heights (acrophobia), fainting (asthenophobia)”—just going to test my pronunciation skills, “being trapped far from home (a species of agoraphobia), germs (bacillophobia), cheese (turophobia), flying (aerophobia), vomiting (emetophobia), and naturally, vomiting while flying (aeronausiphobia).” So, I’m certainly nervous to moderate this talk, but it’s nice to know that you are more nervous than I am. [laughter] So, thank you.

So, in typical form I’ll start by asking Scott a few questions and then we’ll open it up to all of you. As ad revenue contracts and readership habits change, everybody’s trying to figure out how to operate in this new landscape and how to make money in this new landscape. Over the past few years The Atlantic has made a number of strategic moves, including implementing a “digital-first” strategy. The business reached profitability in 2010 for the first time in decades, I believe. Can you describe this “digital-first” strategy and what it means in practice?

Scott Stossel: Sure, to make a kind of long, five-year story short, or actually it’s a 157-year-old story at this point, but the challenge was going back now, to go back just over 10 years, so the magazine had been around since 1857, and it had a series of owners and in the late ’90s Mort Zuckerman, who was a real estate developer, owner of the New York Daily News, actually launched Fast Company, had progressively been starving the magazine. I think he bought it in 1980 with high hopes of using it to give him an entrée into a cultural, literary world, but also that it would make money. I think it did a little bit of the former. He actually, compared to what I’ve heard about how he is at some of his other immediate property, which is very, very hands off, he hired this guy Bill Whitworth who had been William Shawn and The New Yorker’s right-hand man and everyone thought he was Shawn’s heir apparent, brought him on in 1981. And then, early on he invested money and we were (I say we, this was before I was there) able to pay significant amounts to writers, competitive with other New York magazines.

But, over time as Mort realized that he was not going to make money, he progressively starved the magazine and was having to make do with less and less resources. David Bradley, who was a Washington guy who made a bunch of money in the consulting business, bought the publication in the late ’90s. He decided in his second chapter of his career, he had been a guy who had built consulting companies and sold them for hundreds of millions of dollars, he thought, “Oh, I’m a business genius, I’ll now do this with media.” And as many business geniuses learn when they turn to media, it’s a lot harder to make money in that than in just about everything else, except maybe restaurants.

To his credit, he invested an enormous amount of money very early on in everything. He invested in beefing up the staff, in improving the quality of the production values and the paper stock, and the quality of the journalism really increased. The magazines got fatter, we got nationally prominent writers writing for us, we started winning more National Magazine Awards, and we were hemorrhaging millions and millions of dollars a year. I think, for some period of time, into the mid-aughts, we were losing probably 4 to 8 million dollars a year just to keep the thing afloat. He decided, enough is enough, and two things happened at once, which was actually fortuitous because one of the things was an extraneous shock, which was the economy fell off the cliff. That happened the summer after David decided to hire Justin Smith, who was a relatively young, but media veteran who had worked at The Economist in Asia and had developed The Week’s business strategy. And he came in, and I think Justin saw himself as an entrepreneur, he wanted to build new media properties, build brands, do new journalism, and on its face The Atlantic was not an obvious thing because it’s an old brand. David sold him on “Look, what we have is this venerable tradition, keeping aflame the founders [Ralph Waldo] Emerson and [Henry Wadsworth] Longfellow, and those folks alive. But, we can reinvent it and I am now really ready to reinvent it.”

So, Justin came in and did two things that were very, very smart, one of which was painful. The first thing, that was painful, was he radically cut costs, as was necessary at the time. And this was the lead up to the fall off the cliff.

Rachel: By cutting staff?

Scott: By everything. He’s now at Bloomberg, he’s done the same thing there. He hacks every business unit to provide a kind of accounting of everything that they do. So he did that, but he also—well, actually there’s really three things, two of them may be correlated. One is, he rationalized the cost structure. Two, he said, “We need to in this age be digital first, we’re going to turn ourselves into a digital-first company, even though we are a 153-year-old magazine.” And that meant investing in technology, investing in Web editors, really honoring bloggers. And actually this had started a little bit with David Bradley. Before that, he hired Andrew Sullivan who brought a whole bunch of traffic with him for The Daily Dish over from Time magazine.

And then concomitant with all of that it was, we need to refine the brand. And one challenge of being a general interest magazine, especially one that has been around for so long, is that over 150 years we have been many things at different times. Any general interest magazine is always a bunch of different things at different times. And there were periods where we more of a literary magazine; times where we were more of a public affairs magazine; times, in the ’70s when Robert Manning was the editor and he had come from Time and the State Department, they were trying to be a newsmagazine on a kind of monthly basis, which you could kind of get away with back then. So he focused all of this on, what is The Atlantic brand and how do you distill that? And he brought in a brand consultant and all these marketers. And it seemed to be at the time a little bit squishy and bogus, but I have to say in retrospect it was a really useful exercise because basically what we did was thought very deeply as an editorial group, and also on the business side, about what is it that The Atlantic does editorially and what is the distillation of that, and what is our core DNA.

Rachel: What is it?

Scott: Well, for us, it’s ideas journalism, covering the world of ideas, reporting ideas. As our founding charter says, “We’re of no party or clique,” which is in contrast to so much of the political journalism of today. Whether on cable TV or among political magazines, there’s a long spectrum where each magazine has its little ideological bandwidth. We are sort of all over the place, not a bland middle, but as long as something is rigorously argued and intellectually honest we welcome these multiple voices. It’s those things: high-end journalism, storytelling. And we extracted this core DNA and then thought, we’ve been doing this in magazines, but how do we do it in events; how do we do it online; how do we do it in online new—this is now looking a few years down the road, when we launched sub-brands like The Wire or Atlantic Cities and then for sister publications like Quartz, which is a little business online publication; how do you do it for platforms like desktop and mobile. And Justin was very effective at forcing us to think all of those things through.

One reason it was fortuitous is, as painful as the cuts we made were, it actually put us at a—and I had friends at Condé Nast … So, we hit, I guess it was 2007, eight, nine, where everything fell off the cliff and advertising dried up and this was in the teeth of what was already a secular decline in print advertising. We actually were in a relatively good position because we already made a round of painful cuts,we had to continue to squeeze our belt, but it was less dramatic than at a lot of, Condé Nast was shutting down publications, and for us it was more gradual. It was kind of an accident that it happened that way, but it worked out.

Around about 2009, Justin went to David Bradley and said, “Look, circumstances have changed, we promised we’d break even by such and such a date, it’s not gonna happen.” But then things continued to improve, and sure enough in 2010, we actually did break even, very narrowly. And then every year since then, we’re not making huge profit, but we have through a variety of means managed to keep our heads above water.

For me, on the editorial side, my main job is not to worry about our revenues, but it’s obviously a good thing if our owner—we’re independently owned, we don’t have shareholders and all that, but obviously he’s not having to pay money out of pocket to keep the thing afloat. He’s much more inclined to let things proceed as they’re going. So, that’s kind of a longwinded way of talking about it. The other aspects of it—this is driven by Justin Smith and my colleagues on the editorial side, James Bennet, Bob Cohn, and then Justin’s successor, Scott Havens, who’s now moved on, sort of diversifying revenue streams. And that means looking at video, looking at events, looking at things outside of conventional journalism. On the advertising business side, looking at all kinds of new ways of doing advertising and a kind of relentless entrepreneurial experimentation, thinking of ourselves as a start-up. It actually used to annoy me, our business leaders would say, “you need to run yourselves more like a start-up,” by which they meant spend no money and turn a profit really quickly. And actually, at real start-ups they have millions and millions of dollars of venture capital and no expectation of making a profit any time soon. But we got what they meant, which is you have to be lean …

Rachel: Amazon’s never made a profit.

Scott: Yeah, exactly. So, anyways, that’s the kind of longwinded story of that.

Rachel: Actually, two questions really. First of all, does the digital side actually support the print side?

Scott: The short answer is no, because we’re both profitable. But, the revenues on the digital side are growing much, much faster, by orders of magnitude, than on the print side. Early on, for many years—actually, I’ve been around longer, I did two tours of duty at The Atlantic. I was there from 1992 to 1996 and I actually launched TheAtlantic.com. I was literally having to teach myself HTML, I had not idea what I was doing, I’m not a techie guy. We built up a pretty vibrant little website, but there was no revenue to support it yet at that point. Actually, when David came in he initially cut back on that. And then he had a flash of light and realized “Okay, we need to be digital first,” and then reinvested in about 2004 or probably five or six. At that point, there was no digital revenue to speak of, all of our revenue came from selling ads in the print magazine, starting to sell revenue in sponsorships, a small amount of traffic online.

If you look at between, I’m going to get these numbers not exactly right, let’s say 2006 and now, I think we have about 500,000 unique visitors, very little digital revenue and we were making a bunch of money from print circulation and a bunch of money from print advertising. What’s happened since then is actually our print circulation has held steady and our digital circulation, which is to say to say sales of, people subscribe on the Kindle or the iPad, we’re not spending a ton of money marketing that, it’s not huge numbers, but every time we get one of those it goes right to the bottom line. Print advertising, as everyone knows, has gone like this [draws a line downwards]. It seems maybe, a little bit, temporarily it has stabilized. It would be great if it was not just temporary.

But, the magazine itself on its own terms is still profitable. Over the last two years, the digital side—I don’t know the point at which it broke through to profitability—but it did and now, knock on wood, this year has started out phenomenally well, where, I don’t think this is proprietary information, but the projection of the April digital revenue will be up 200 percent over last year, which was up X percent over the year before. And again, just in traffic numbers, we’ve went from those 500,000 unique visitors to, across all of our sites, which is to say TheAtlantic.com, Atlantic Cities, Atlantic Wire, 25 million uniques. I think it’s 18 million or 20 million to TheAtlantic.com.

Rachel: So given all this effort of going into digital and all the success of digital, what do you think this means for the venerable print magazine that’s been around for so many years? Do you foresee that, in a decade from now or two decades from now, that there will still be the magazine?

Scott: Really good question and we ask ourselves that question all the time. I think, yes, it will and with some degree of confidence I think that. Will that magazine exist primarily in print or will it be delivered digitally? I think if you’re looking, I don’t know about five years, but 10 or 20 years down the road, I would guess that the vast majority of people consuming it will be people consuming it on tablets or whatever devices of the future that don’t yet exist.

Rachel: Robots. [laughs]

Scott: Yeah, exactly, or beamed directly to our frontal cortexes. [laughs]

It was interesting because Scott Havens who came in, he had been at Yahoo News and then was at Portfolio when Condé Nast came in, he was our director of digital. I remember him coming in, and he will say this himself, and I remember talking to him and he said “Print’s going to be dead in five years. There will no longer be a magazine.” And then he stuck around, he became the president, and I think, partly looking at viewer habits and partly more deeply immersing himself in our brand in particular, he now says, he gave a presentation at South by Southwest a couple of weeks ago and he says, “I don’t see print magazines going away anytime soon.” They may shrink, they may shrink a lot. They may kind of change, they may become more of a coffee table thing, a kind of premium product, but there is a sort of residual attachment to print, certainly among the readers, or some readers, and some—knock on wood—advertisers. But again, it’s so variable from quarter to quarter and year to year.

My hope, from my own parochial perspective, and as the guy who presides over the print magazine, is that we’ll continue to get enough print advertising to invest in the print product. But, I’m a platform agnostic myself and this really gets to interesting questions about, and we talk about this a lot too, again none of us are in love with paper per se, or ink or anything like that. In fact, if we could suddenly convert our 500,000 print subscribers, all of them pay—even though you get all the content at this point available for free on the Web, if they were magically converted to digital subscribers and we scrap the print magazine, our bottom line would be so much better. We could pay writers so much more, because we wouldn’t be paying for all the printing and mailing distribution costs. But we’re not there yet and we can’t force the issue because we’ve got 10 million dollars worth of print subscribers. So, we’re constantly evaluating lots of different options. We talk on and off about whether and when and what kind of payroll we might bring down, to kind of protect the print subscribers that we have so they’re not disincentivized to keep subscribing. On the other hand, our digital traffic is accelerating so fast, driven largely by a shift in the social Web. We’ve done very well in the age of Facebook and Twitter sharing. It has caused a surge in traffic, which has caused a surge in revenue, so that now we’re like, wait a minute, maybe we don’t want to bring down a wall because that might stand against traffic and would cause problems.

So, it’s constantly monitoring the environment of reader consumption, advertising preferences, and trying to figure out what kind of new products can we produce that caters to both and how do we sustain the journalism. And what I was starting to say here is, and I think most of you know working in various forms of media, that the economics of print and digital are very different at this point. And for us it creates a weird bifurcation; our pay rates for the magazine have come down in recent years relative to what they were, I think in line with the market, but they’re still considerably higher than our standard rate on the Web. What justifies that? At some point I feel like Web pay rates are going to have to come up and print rates will have to come down. And we have plenty of native digital pieces that are conceived and written for the Web that are hugely important, really well done, lavished a lot of time on. But, because of the apparatus of producing a print magazine, so much more time goes into the writing, the reporting, the editing, the fact checking, the design of those magazine pieces. So the fear is if that were to suddenly go away, literally the process by which we produce the magazine which forces decisions—we reject far more things, we end up having, out of necessity, more quality control and the process itself forces a lot of time to be lavished on each individual piece in a way that online someone has an idea at nine in the morning and then posts something at 9:40 and maybe it goes completely viral.

If you’re sitting on the corporate floor with your green eyeshades and you look and say, “We have a 22-year-old kid we’re paying not very much money who can write a post at nine in the morning that goes totally viral and gets all the ads … Or we have these experienced journalists who we’re paying much larger salaries for, and it costs much more money to subsidize their reporting and the whole apparatus around producing that piece. Gee, shouldn’t we be getting rid of all of those expensive ones and just doing more of that?” And sometimes there has been some of that tension, but I think there’s more of a realization that you need both. Again, this gets back to brand, that if our brand is partly associated with rigor and length and a careful curation of what we do. So these are all kinds of the questions we are struggling with at all times.

Rachel: About the paywall issue, where do you come down on this? I know you were saying you go back and forth.

Scott: It’s nowhere. [laughs] And everywhere. And I’ve been working with the magazine long enough that I’ve been through when we first launched the website there was no paywall, then there was a paywall, then we pulled it up, then we pulled it back down, and we took it back up again. It’s funny too just watching, I think most journalists don’t want a paywall. Or, at least at first blush you think, and I remember this 10 years ago, “no, no, I just want to get read, I want my stuff out there, I’m just in the business of disseminating information, and any kind of impediment you put between the reader is going to interfere with that.”

I think as we’ve gone through the upheavals of the last few years, there’s now the recognition that, wait a minute, we realize that we need to communicate to people that it costs money to do newsgathering and it’s not a free thing. So, trying to square that circle of you want to be as widely read as possible and yet you also want to be subsidizing the serious journalism. We’ve been working with different technologies to figure out what would be the right kind of paywall to bring down, but I think at some point, and again I’m getting ahead, this is not set policy, something along the lines of what The New York Times has done, and I think they’ve just launched a whole bunch of new products. But, where you have a meter registration system that is for the most part not cumbersome; if you’re a casual visitor you probably won’t ever even hit the registration, if you come a lot you will and then maybe if you register we get information about you and can invite you to things. So, it’s an effort to identify and then offer premium products to the really hardcore Atlantic brand lovers. This is, again, a matter of constant discussion and now that we’ve just had a change in leadership, with the presidency, I think it’s all being re-evaluated again.

Rachel: And what about social? You just mentioned that The Atlantic has been really successful in creating this, for a lack of better word, “viral,” buzzy … So, what goes into making something shareable and, as an editor, is that something from headline decisions to even story assignment decisions. Are you always thinking about shareability?

Scott: Yes. More on the digital side initially. Originally, a few years ago, it was how do you do search engine optimization, all that kind of stuff. But, John Gould, who is now as of yesterday or the day before, the editor of TheAtlantic.com and Bob Cohn before, he and all of the digital editors think deeply about this stuff. They’re simultaneously producing the journalism but also approaching this almost like academics, because it changes so quickly. A small change in Google’s algorithm or Facebook’s, what they prioritize, can suddenly radically change our traffic, whether we were banned from Reddit for a while which hurt our traffic …

Rachel: Why were you banned from Reddit?

Scott: It was some stupid thing where they thought we gamed the system or something. We’re out of the doghouse and it’s fine now.

But in some ways it’s been, from my perspective almost by osmosis even though I’m not deeply immersed in the traffic and I look to see how our print pieces are doing online because it’s a good metric. What we can’t know is, we have 500,000 print subscribers, I can know how our cover story is doing or random feature story is doing online because I can see exactly how much traffic it’s getting, how many Facebook likes and shares it’s getting. But, does that necessarily correlate to what the people who are reading it as a magazine bundle are reading? We do some reader survey data. But, you start to develop a sense of what will do well. Again, this is what has been very nice for us, is that we didn’t have to change that much. The sorts of pieces that we do, both in print and online, tend to go viral, and not every one, but the kinds of pieces where it somehow resonates with a conversation that’s already happening. Our current cover story is about the overprotected kid and it’s already set the record for the most, I mean anything that’s about parents and kids … It’s got 300,000 Facebook likes or something like that, or shares, and well over a million uniques.

Audience member: Do you have the cover, Rachel?

Rachel: Yes, I do. Here it is, “The Overprotected Kid.” And I have to say, as soon as this came out it totally lit up all of my social feeds because I’m in this demographic.

Scott: And what’s interesting, we don’t know yet whether that will …Our biggest newsstand seller of the last five years was Anne-Marie Slaughter’s piece two years ago about why we can’t have it all. Biggest traffic piece of the last five years and biggest newsstand seller. There you have a complete correlation. We’ve had other cases where there’s no correlation at all or almost an inverse correlation.

Rachel: What would be an example?

Scott: And it goes both ways. A couple of years ago in the fall of 2011 we published a big piece by Taylor Branch on college sports. Huge online sharing, traffic, discussion. On newsstands, didn’t really do that much. I did a cover story that was an excerpt from my book, that did well online, but so far it’s looking like our best seller on newsstands since Anne-Marie Slaughter. Our theory is that newsstand is important, the difference between our selling 30 copies, well 30 copies we’d have to be terrible, 30,000 copies and 80,000 is enormous for our bottom line and it signifies all kinds of things to our advertisers and things like that. But, it’s a horrible business: you print all these copies that don’t get sold, it’s in secular decline. I think there are all kinds of theories that it might be, because it’s all being offset by people buying single copies on their mobile devices. It could simply be, I read one study where a lot of magazine purchases are impulse buys where you’re standing in line at the checkout counter. But, in the old days you’d be sitting there like, should I get a pack of gum, but now you’re sitting there doing this [gestures to phone] …

Rachel: With your phone.

Scott: So you don’t get to make those impulse buys. We are trying, as part of our overall strategy, maybe still care about newsstand but deprecate that a little bit, and invest more in digital subscriptions … and in mobile consumption, everybody knows and we are well aware, I think we just reached 50% of consumption of our online content is through mobile devices, iPhones and tablets. And the other place we’re investing a lot in is video. Video is the one place—I think this is true for a lot of media organizations—where a lot of time we are trying to find enough advertising to support the journalism that we are doing. In video, we are trying to find enough video to support the advertising that would like to come support us. So, over the last few years we went from having one video person to having Kasia [Cieplak-Mayr von Baldegg] run a team of now five or six that’s just fantastic. And they still can’t keep up with demand so I think that’s where a lot of growth will be.

Rachel: Are these original video pieces or are they video supplements to your stories?

Scott: All of the above. It’s some pure video curation, where she’ll partner with other filmmakers and we’ll just put it on our site and then we’ll run advertising before it. More and more, now that she has her own production team, it’s doing things that are, so for our next cover story for instance she just shot a video with two co-authors and that is a complement to the cover story. In other cases, it’s wholly original programming, where they’re doing, in fact, mini-documentaries that they present as …

Rachel: Docs, yeah. There has been a movement to share traffic data with journalists. David Carr just wrote a column about it. And does The Atlantic share this with its staffers, and what’s your take on this?

Scott: It’s not a question of sharing, it’s available to everyone. I think that there is, and again since I’m not on the digital side primarily I’m sort of watching this from some remove, but they are, and I think this is again because Bob Cohn and John Gould are very effective at managing healthy competition, it’s a very collegial group. But, they are aware of whose pieces did what. Compensation is not tied to this, and there’s a recognition too that there are some pieces that don’t do well. Traffic is not the end all, be all. Traffic is very important, but there are certain pieces that are just important to do because they are in the public interest or because they are supporting the brand. That recognition permeates everything.

I do worry that the more transparent and available the data is, there’s a natural, what’s the word, sort of race to the bottom, the lowest common denominator, cat videos that kind of stuff. We try to be smart enough about that, and yes we’re not above doing the pure traffic play. But we realize that for us, we’re not going to be able to compete with BuzzFeed or Upworthy on that because they’re better at it than we are, and they’re more kind of down market, even though BuzzFeed does serious journalism, as well. But, the stuff we have to do has to be Atlantic stuff and that works for us, because there’s an audience that seems to want it.

Rachel: The Atlantic got into some hot water a few years ago for branded content sponsored by the Church of Scientology. Branded content, as we all know, is everywhere. So, why do you think that was so particularly contentious, and what happened there?

Scott: That was sort of a perfect storm of awfulness, for about a day or two. [laughter] But it actually, I think in the end, but again it would have been better if it hadn’t happened, but we responded I think very well, and it was a very good, instructive learning experience for everyone concerned. And to this day I don’t really know where the bad decisions happened. Native advertising is a sort of fraught thing, because on the editorial side, it’s a problem for us if you can’t tell the difference between what’s an ad and what is true editorial content. Obviously the advertisers want for things to be embedded in the stream and look as “native” as they can. I have no problem with that as long as it’s properly labeled.

In that particular instance, there was a combination of it wasn’t completely properly labeled, the fact that it was Scientology, which is sort of a controversial church, and immediately there was this huge reaction. Clearly we had to fix our decision processes at that point because it should have never made its way on to the site.

Coming out of that, what we did, legal counsel, and the business side and the editorial side came up with a set of guidelines for what and how these things need to be labeled, the sorts of things we would accept and that we wouldn’t accept, what we would call it. Since then, we really haven’t had a problem and, also, since then many other people have followed in our direction. You now see The Washington Post, The New Yorker, they’re starting to venture into this territory. So, it was a painful, but useful learning experience. I don’t think, it was not a good thing. I mean for all of us our journalistic credibility is the most important thing we have and if anyone comes away with the impression that we are now simply running propaganda for what people consider a cult, that’s not a good thing.

So, what was I going to say? Oh, excuse me. So, we have a piece in the next issue by a guy at Harvard Business Review named Justin Fox. He’s looking at the launch of all of these new, you’ve got Jeff Bezos is investing all of this money in the Post and you’ve got John Henry investing in the [Boston] Globe. But then, more strikingly you’ve got the [Pierre] Omidyar 250 million dollar investment in his new thing, you’ve got Vox media with Ezra Klein, you’ve got the BuzzFeeds of the world. So, are we on the cusp of this new era where we have these big start-ups that are actually going to become profitable? He has a couple of sobering points. I think one point relates to native advertising. The sobering point is that there was a period—up to a quarter century I guess—where these media companies were making 25 to 50 percent a year profits. That was an anomaly and for most of the century before that and the period after that, journalism as a business is a very marginal, low margin business. The Pulitzers, the Hearsts, up to Bloomberg, they had tons of money from other sources that were not journalism. I have a friend who works at Bloomberg who jokes that it’s a petro state, where the petro is the terminals. It’s great because they can spend, it doesn’t matter.

But the other point that Justin Fox surfaces in this is he goes back and looks at these old, and in the old days, and again I’m not endorsing this, but you had in fact native advertising in the form of the company which would go up and give cash to a reporter to write a puff piece and that was what subsidized journalism. We now have clearer Chinese walls but this was kind of ’twas ever thus.

Rachel: I want to shift gears for a little bit and talk about your book. I write about workplace issues and my colleagues and I have written a number of stories on the persistent stigma of mental illness in the workplace. Very few executives, let alone rank-and-file workers, admit publicly to suffering from mental health issues even though statistically many of us experience them, and you obviously wrote about it in this extremely public forum, on the cover of the magazine and also in your book. So what was the reaction among your colleagues, were they aware of your …

Scott: It was interesting, they were not aware. I thought they were more aware. I didn’t really know how aware they were until the book came out and I had people coming into my office saying like, “I had no idea, do you want a hug?” [laughter] which was a little uncomfortable, but nice. And it was funny too because I could never have what, my colleagues basically took what I’d written in the book and then sort of distilled out all the most florid embarrassing personal stuff and put it together in this memoir-ish package and I could never, I mean I could partly ignore it writing the book, for many years I thought it would never get published, it’s embedded in a lot of science and history and I was kind of using my own case study as it were to kind of try to inflect and illuminate these things and in some ways, then they put together this thing where it’s all kind of a full crazy distilled into 15 pages and so in some ways it was like ripping off the Band-Aid because you know I talk in the book about having sort of misgivings about having in fact gone through great lengths to cover up my issues with anxiety for 35 years, I’m now basically putting it all out there and you can’t put it back in. I have to say I didn’t know how this would, what the effect would be on me or on my colleagues. I didn’t want them looking at me any differently or treating me with pity. And I have to say at a very basic level it was like the thing came out and the world didn’t end, and I had lots of colleagues coming up to me saying, “We had no idea,” I had plenty of other colleagues coming up saying actually I have this issue or my mother has this issue and it got to the point where I had people coming from so many different departments I started to think maybe I should start having office hours. [laughter] And it was funny too because in the book you know I’m not better, I’ve sort of come to terms with it and gotten good at managing it but like people seem to want to come to me for some kind of help and I keep having to say I’m not a physician, I can’t prescribe you anything. But something about I guess my admitting to all this stuff provided a sort of consolation or recognition I guess, that made people feel comfortable about coming up and talking about it.

And I honestly didn’t go into writing the book thinking a part of my, as a crusader, like I want to lift the shame and stigma of mental illness. But I have now kind of been co-opted into that cause and I have to say I feel good about that. Just the number of people who’ve written in to say how much this helped them, either because they themselves suffer from these issues or because family members do and it helped them to understand that better has been gratifying and validating. And to your point about in the professional world it’s sort of taboo to talk about this stuff from understandable and maybe sometimes good reasons but you know there’s a group called, it’s based in Seattle, it’s called something like Stability. It’s run by a woman who’s a super successful consulting executive who suffers from bipolar disorder and she’s basically trying to set up this network of professionals who suffer from various forms of mental illness and to provide mentorship for other people coming up to let them know that it is possible to manage these things and that in fact the diseases themselves might come kind of co-presenting with other personality traits that are actually useful in the workplace.

Rachel: I have a bunch more questions but I want to open it up to you guys, in the audience.

Audience member: You talked about branding The Atlantic as a start-up and sort of defining that. Can you identify maybe some things that give your brand the vitality it seems to have? Because journalists are generally very conservative, so operating in this climate of constant innovation, how have you made that happen?

Scott: Good question, and its partly, actually you mention culture; I mean that’s one thing that has become more and more apparent to us. I mean obviously we have to, on the business side people are all, and if you’re an editor you’re thinking what is your editorial strategy and that’s really really important. But we’ve actually come to realize, most strategies, you’re flying blind, you’re making assumptions you’re trying to project based on existing numbers and projecting on how many people are going to have iPads and who’s willing to pay for this or that. So that’s important, our business side people think about that all the time. But we’ve all sort of been thinking what’s most important is our culture and that culture consists of a few different things. Most important for the journalism is editorial values, that we care about excellence, we care about in hiring, you know, we want exceptional talent. We care about all of the journalistic values. But we also care about, and this is something that was imported maybe newly as sort of part of the digital-first era, entrepreneurialism, experimentation, willingness to fail, everyone being aware of what all these changes are really, and we have a number of, once you have a few key people who are very forward looking it tends to be kind of infectious and they are always wanting to be constantly reinventing what we do, even as we are trying to remain true to those core journalistic values, and sometimes those run into tension.

Actually I’ve never really thought about this before, but for a while we moved into, as many journalistic companies did, into doing slideshows, because people like to read them and they generate a lot of traffic, because you have to click through them. And then there’s wisdom, John Gould and that kind of people realized it’s kind of cheap traffic. And we will still sometimes do them, but it’s not us in some way. So what’s us? So we start doing more things that are sort of data driven, where you have a piece that’s really just a bunch of charts, so its this kind of constant willingness to experiment, and now we have data all the time to see what is working and what isn’t, being really aware of that as people on the business side and as journalists, you know, what are people reading and what aren’t they. Partly it is having to do things, be very resourceful in how you do things because you don’t have tons of investment renewal as opposed to if you have Pierre Omidyar giving you 250 million dollars or Ezra Klein, there’s only … We try to do things on the cheap to see if they work, and if they work then we can justify investing more money in them. So it’s really a cultural thing, being willing to be rapid adopters and rapid dropping of things that aren’t working. And that’s also where having the magazine continuing to be more or less the magazine it always has been provides a kind of balance so if we’re trying to do something that ends up seeming kind of goofy online or a failed experiment, well the next issue of the magazine still comes and we’re still doing that sort of serious journalism even as we’re also experimenting within the magazine, changing what we do. It’s kind of a mindset of always be experimenting.

Audience member: I wanted to ask about the big cover story, now it’s "The Overprotected Kid," and in my day "The Organization Kid," that was my freshman year of college everyone was …

Scott: You were one of those kids.

Audience member: Yeah I was at Princeton too.

Scott: So you really were one of those kids [laughter].

Audience member: So I was just wondering about your process for finding those stories and also what does the cover story look like in the digital age, is it just like the homepage story for a week, or I mean you mentioned that that discipline of actually creating the physical magazine does lead to certain habits and processes and how does that, what does that look like if there wasn’t the print part?

Scott: That’s a really interesting question because, in response to the first question, we realize that the cover story is the most important thing we do in the magazine because it drives newsstand sales which aren’t necessarily the most important, but it drives mindshare, and people remember “The Organization Kid,” or “Why Women Can’t Have It All” or going back there’s the “Broken Windows.” The most important thing we can do is you know, we need almost to come to three or four, we’d love to do it 10 times a year, but if we can have three or four cover stories that everyone is talking about it expands the visibility of the brand, it’s good for our readership, it’s really really important. The challenge is we only have—we come out 10 times a year, and we have a limited amount of funds. Tina Brown, I read about the Tina Brown New Yorker era, this sounds like a fabulous luxury to me but also a huge management challenge, they would literally double assign, for every issue they would assign two times the number of stories, which means as an editor that’s great because you can pick only the best and the rest get killed and of course then you get a bunch of unhappy writers and that is in fact what happened. The funny thing about the cover is that, we do lavish more, collectively more, editorial brain power goes into trying to figure out what the cover should be, trying to think about how to present it, the editing, the fact checking, the design, but, and this is where there’s a weird vestigial thing even as we’ve moved into the digital age, still a lot of what drives attention to a cover story is whether you get broadcast media, NPR, or the morning shows. Again this is almost like a vestigial thing from a previous age, like the producers of “Meet the Press” or “Good Morning America” or “Morning Joe” or what have you, “Colbert,” they still like, what’s on the cover matters to them more. We’ve thought about this you know what if we did take the radical step of not having a cover story, would they suddenly be like wait what’s the cover story? Do we say well it’s this thing that we’re featuring on our homepage? I think at some point they’ll adapt to that, but at this point really the mere fact of being on the cover means that producers who book our writers on shows, it means something to them. Again, that’s probably a lagging indicator, left over from some old version of the journalistic system, but it matters a lot in that way.

There’s no science, I wish there were, for how you come up with cover stories, I mean it’s the constant trawling for the kind of story that is going to generate conversation. But we’re also looking at over the course of a year you want to have a diversity of stories. So you’re getting important foreign policy stories, as well as parenting stories, as well as domestic public policy stories, as well as sometimes narratives that have some kind of significance. And there’s a temptation too to trawl, or a fear that we’re going to be seen to be trawling, some people would have accused us that the Anne-Marie Slaughter piece was trawling. I would say it absolutely wasn’t, it was a very original piece. But there’s a temptation to go back to that well, you know we did so well and we know people want to read about it, so what’s the next version of that? And we’ll sometimes steer away from pieces that seem like we’re going off into that. You’re thinking about both the big picture of what the other run of stories in a given year are, but also what is going to drive traffic, what people are going to care about, what’s going to do well on newsstands, and what’s going to advance the public interest and the national conversation obviously.

Tim Rogers: I wonder if you could talk a little about if there is a similarity between writing for the cover and writing for clicks, I mean to a certain extent it seems like they’re both a bit manufactured because you’re going after a specific audience. And are either of these two limitations to sort of journalism that you would do in a vacuum or in a perfect universe or something?

Scott: Good question. I mean, not really. There are differences, and it’s funny too because there are cover stories which are 15,000 words that go totally viral and then there’s a 40-word post with pictures that also goes totally viral, very different processes by which those come together and obviously the structural complexities of that cover story are different. Clearly, we can now see if we publish a 15,000-word story, and people are reading it online, we can see when they’re bailing out, we can see how far into a story they get, and it’s kind of what you’d expect that the spinach-y stuff, they’ll bail out earlier, and so there’s a temptation to be like juggling plates and juggling flaming torches because people will lose their attention. With narrative pieces its easier, you get a really taut narrative, they’ll read that. I don’t think it’s compromised the journalism, I think at all places, newspapers, this is I guess the great tragedy of what Craigslist and the Internet did to newspapers, it was always the case that far more people were buying the newspaper for the sports pages and the comics and the classifieds and that was subsidizing the Baghdad bureau and the metro bureau and now that’s become disaggregated. We’re mindful of that and there are times I’m sure where, I mean we were in a vacuum when we were producing these stories 15 years ago, and every editor has in his or her head, how is this going to play online, and I think that could have a corrosive effect but it has an effect on how you think about you’re printing the story. I argue that’s a good thing though because we just have much more information about what readers are willing to consume and how long a piece they want to read. And it’s the balance too between are we giving readers what we think they should read? Yes. But do we also have to meet them somewhere in the middle and know what they’re willing to read and what their patience for certain kinds of pieces are? Yes and we know much more about that than we did 15 years ago where all you would get was over the course of the year you’d get a little bit of subscription data and you could tell how things did on newsstands.

Audience member: You mentioned the constant willingness to experiment, could you give us like two examples, maybe one that turned out to be successful, another maybe not so successful that you have been doing in the past like two years?

Scott: Sure, one experiment which its too soon to tell whether it’s successful or not, is we launched a product over a year ago now called The Atlantic Weekly which is meant to again try to find readers where they live. We talked about the lean forward experience when you’re at work and you’re reading things on your desktop, or you’re on your iPhone while you’re standing in line, you’re reading things quickly you’re skimming you’re scanning you’re not necessarily wanting to lean back and read longform pieces that are 8,000 words. And we can tell also, we can even tell what time people are reading different things, so we know like at lunch time there’s a huge spike because people are sitting there at their desk reading, we get more traffic during the work day when people are at work and they should be working but of course they’re browsing. But then at night like after dinner you’ll see that more people are reading on their devices, and they’re probably like lying on the couch. And we developed this product called The Atlantic Weekly again with very little resources to start out which was trying to basically cull from everything we were doing on TheAtlantic.com in a given week, designing it in a better way, sort of applying a little bit more editing love to it, and then presenting it in a way where you could download it, you could subscribe or you could download it any given week and it’s sort of an experiment. We now have in the order of tens of thousands of subscribers, it’s not a huge number, we’d like to make it bigger. It sort of remains to be seen whether, we’re kind of poised between do we invest a lot more in it and try to grow it or at some point to we decide its not good enough and we shut it down. I think the likelihood is we’ll go toward the former. So that’s where it’s an experiment that is still ongoing, and I think it will be a success.

Let me think about other things. This is again, online they’ve discovered that, this is again through experimentation of just daily, pieces of mid-length tend to do more poorly than pieces of really short length, not surprising, or really long length, and that was sort of surprising. And it kind of suggests that there’s an appetite for snack food, stuff you can get really really quickly, the mid-range stuff, 800-word pieces, sort of more of a commodity, you’ve got so many things, so many outlets producing op-eds, things like that, sometimes the mere fact of length, if you publish it online a piece that’s 5,000 words and you give it a special presentation, it’s almost like “oh well this much be something special” and we sort of decided that there must be some sort of intrinsic editorial merit or quality to this that really matters. So that’s another sort of example where trial and error has led us to change, so we now do fewer of those mid-range pieces. I mean there are various other things too, where we’ve done in video, we’re very kind of promiscuous in our willingness to experiment with different kind of partnerships, both because in this kind of hostile strained environment if someone else can bring something to the table, either distribution or content, sometimes we have the content and they have the distribution, sometimes vice versa, we’re very willing to try all those kinds of things, a lot of them don’t work because the audiences don’t match up, but sometimes they can be very effective at generating traffic for everyone.

Alison MacAdam: I have a comment and then a question, the comment is just to tell you that I enjoyed your article while on an airplane, and having a less severe version of some of your flying issues I was only able to enjoy it thanks to my favorite flying drug Dramamine, so, I understood some of what you were experiencing. My question is totally different, which is back to the question of things that are changing in journalism right now. As folks at The Atlantic watch these brand name journalists go off and form their new things, you of course have some people who, I mean you had Andrew Sullivan, you have some people who to a certain degree have that, have a certain brand cachet, what are the conversations that you have about that and the management of Atlantic the brand versus your writers the brand?

Scott: Really good question, that’s another thing we talk about a lot, it’s a screwy analogy but I’m a football fan, so they’re always having to figure out when you’re signing some superstar to a big contract, obviously you want the big superstar to come onto your team because they’re going to do great things, but if it costs an enormous amount of money … I mean football’s different because our people aren’t going to rapidly decline when they hit age 28, but you do have to balance, have some kind of cost discipline in terms of your overall budget and being able to manage. Actually, David Bradley helped drive this, we brought in a bunch of kind of superstar bloggers, Andrew Sullivan being the most prominent, but Ross Douthat who then migrated to the Times, Marc Ambinder, Matt Yglesias, and various others, Ta-Nehisi Coates who’s still around. And we’ve realized that it’s more cost effective, and we do still, we just hired David Frum, who’s kind of a brand name and has joined, Peter Beinart kind of is, we share him with National Journal. So we want a mixture of people who are established brands, they tend to be more expensive. We really want people to exist within The Atlantic brand, they can have their own brand but it needs to be aligned, we all need to be moving in the same direction. The problem we’ve had lately, we’ve gotten very good at, again this is all credited to the folks at the digital side, we’ve hired some sort of 22-, 23-, 24-, 25-year olds, who come in, they’re making a small amount of money, and then they become so good that immediately they become visible to all the other media outlets and then they start getting poached and their salaries get higher and higher, so we try to strike a balance there. This is different from in the early, free-spending David Bradley years. He did go out and we hired great talent like Mark Bowden and William Langewiesche, who was already there, and David Brooks at the time. It led to great journalism. It also led to this unsustainable editorial cost. And I think the fact that Frum is coming—he’ll come to us part-time, we’ll get a big chunk of him. He’s an incredibly productive journalist, so I think he’ll really get great audience and we’ll get a lot out of him.

Rachel: Can I just chime in for a second on the issue of costs? Last year there was a very well-publicized exchange between a journalist, Nate Thayer, and an editor at The Atlantic. On his blog he posted a series of e-mails between him and the editor where the editor approached him to basically repurpose an article for The Atlantic but said, “Hey we have no money to pay you, do you still want to do it anyhow?” He wrote, and I quote, “I am a professional journalist who has made my living by writing for 25 years and I’m not in the habit of giving my services for free to for-profit media outlets so they can make money by using my work and efforts by removing my ability to pay my bills and feed my children.” And this generated a huge amount of publicity and James Bennet, the editor in chief, posted an apology. And I’m just curious, what’s your take on this? You alluded to the fact that there are very tricky digital economics.

Scott: Well that was—coming not that long on the heels after the Scientology [laughter], that was another fun one too … And you know, granting that Thayer had a point, unfortunately he sort of took it out on one of our editors who was acting in good faith. But we, nowadays, by and large pay something for just about everything. There are exceptions where something. sometimes book excerpts, will be taken because they are looking for book promotion and they know that the piece in The Atlantic is worth something. But we try now, and I think do, pay for everything unless sometimes it’s a politician and they can’t be paid or what have you. But the economics are still skewed. This is where we would love to get to a point where digital advertising—because we are now breaking even but we’re not flush—tries to sustain an enterprise where we can publish lots of great journalism both by our staff, and we rely much more heavily on staffers than we did before, but also on freelancers. And again speaking not just about my larger concern—this has been true for a couple of years or I guess more than a couple of years, since the invention of Internet journalism basically—is that it’s never been easy to make a living as a freelance journalist. It’s so much harder now because prices have been driven so down because there are so many outlets. Now on the one hand there are so many more places you can publish if you’re trying to start out, it’s much easier to build up a clip file, you can build your brand, but the pay rates are so low, that it’s not an ecosystem. Again this is not unique to The Atlantic. We pay a lot more than some places, which don’t pay anything at all. But if you’re a freelance journalist, that’s not an ecosystem, given the existing pay rates out there, where you can make a full-time living very easily, and that’s the reality that someone like Nate Thayer is dealing with and it’s got to be incredibly frustrating.

Rachel: That’s why I’ve never gone freelance right?

Scott: Exactly [laughter]. Now this is where if we can get through to whatever the business model that will sustain us all, it would be good for the journalistic enterprises and the writers who sustain them with their journalism, we’ll be in a much better place.

Ravi Nessman: So building on that, it seems like you described almost two different products. You have the magazine where you have very limited space, you’re incredibly discriminating about what you’re going to publish, you pay quite competitive, very nice rates to people who are relatively famous and well known in their field. And then you have the Internet which is this gaping maw demanding to be fed and to draw traffic where you don’t have the luxury, the ability, the want, whatever, to pay those kinds of rates, to pay in some cases anything like Nate said. But also you’re in a period of transition, where at some point in the next five to million years the magazine’s going to migrate over towards the Internet. How do you see being able to keep the integrity of the magazine as it comes on the Internet? And I think one thing I find very interesting is that when you go to the website, the magazine is still differentiated, you’ll flip to the next article and it’ll say “in the magazine” like, “This one’s a little bit better made than the one that you just clicked on.”

Scott: Although there’s not actually that much difference. Because some people say the opposite, that you can’t when you end up on a given page, if you were coming in through a side door, a tweet or a social media link. We recently have introduced what we call our enhanced story template, which we put most of our magazine feature stories into, but also some of our more ambitious native Web pieces into it. The idea is to signal, “Ok this is not just any other story, something that was done in 15 minutes, this is serious.” But still it’s sometimes hard to tell. You could show up in a magazine feature and not know the difference.

You’ve asked kind of the million-dollar question which is, and I think its doable, but if you sort of imagine that suddenly the magazine, with its production schedule and the sort of forcing factors that come with that—one is you have more time, but also deadlines, but also a limited amount of space. All this forces decisions and a process and everything goes through the fact checking and the copyediting. If suddenly that apparatus, because the print magazine doesn’t exist, disappears, then what do you have? Is it like you have the enterprise team within the newspaper and it’s like they’re doing the longer form pieces and everyone else is just covering their beats and just doing things on a daily basis? I don’t know. That’s kind of an open question. We don’t seem to be close to having to confront it imminently. But it’s something we think about. So I don’t know what the answer is other than that we would probably try to designate—I will say too that there’s been kind of a convergence, now a lot of the front of the book, the magazine, is produced by our Web staff. They’re very very good and they do smart, sort of ideas-y journalism. And they have, on average, you know for a long time we were kind of experimenting with what to do, we were publishing all kinds of stuff and there was always some kind of quality control but there was a high degree of variability and our best stuff was very very good and our weakest stuff was, I think at any website that published a lot of stuff, not so good. I think that over time, through the work of our dual editors, the quality of our best stuff has only gotten better and the quality of the weakest stuff has gotten much much better. It’s sort of striking. I think that’s probably reflected in our traffic—that we figured out sort of what an Atlantic quality piece is, and that’s true even if it’s not something that you can lavish the full kind of magazine treatment to, but it’s something we have to figure out. Or not, I mean maybe the way the world goes is the expectation becomes everything is just cheaper to produce things more quickly and people want to read it and we can do pretty good stuff and we lose the fact checking apparatus and we lose the copy desk. I don’t foresee that happening any time soon. I think it would be kind of tragic if we were to lose that, but it’s not unimaginable down the road.

Jeff Young: Yeah I was curious, events came up, it sounds like they’re something that are pretty successful for you all right now. I wondered what are editors’ role, the editorial folks’ role, in putting on those events in general or what’s the philosophy there?

Scott: It’s evolving, in part because the woman who has been running it for a long time has just moved on to take another job, so we’re actually looking for a new president. I mean, basically, what we really are moving towards—for a long time events was kind of an autonomous unit and they were very very successful at putting on events that would attract both an audience and sponsors. And they were good events. We have this big partnership with Aspen, where we do the Aspen Ideas Festival, or with Bloomberg we did this big thing called CityLab last year in New York. We are trying now to make a concerted effort to, and editors have been consulted, we are often the moderators, we’re sometimes the panelists, but it was kind of done with a separate editorial group under Events. We’re now trying to bring events under our overall Atlantic umbrella with an eye towards making sure that they’re even more interesting than they have been, that they really fall within The Atlantic brand, that they appeal to a broad range of people who might want to show up rather than just kind of a narrow wonky group. We’re very good at putting on these wonky events. We will continue to do those, but what are ones that are more cultural, more along the lines of what The New Yorker Festival does? So it’s very much a work in progress, but the way the new structure’s going to work, really it’s the way the structure works now too but James Bennet, who’s the editor in chief, has answering to him the events editor, and I think there’s going to be a lot more stuff coming from both the digital editorial team and the magazine editorial team—actually coming up with, “Hey I think we should do an event on this,” and then going to the events team and working with them to put something on. For a long time that was our fastest growing, in terms of just revenue and profit growth. It was such a big, there was so much demand for it. Everyone has realized that now and that’s basically gotten very very crowded. You’ve got, even just in Washington where we do a lot of our events, you’ve got Bloomberg and The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal. So it’s a little bit trickier, the way forward there.

Audience member: You mentioned video and how the magazine is getting more involved with video, and as somebody who does make a living as a freelance journalist I’m always curious about what areas they’re looking for in the market. Are you looking for people that have video skills and other kinds of more digital skills than you traditionally have in the past? Or do you really want to sort of do that stuff on your own and have people specialize in different aspects of the story?

Scott: I would say both. Now that we have a video team, we can take someone who is really an old-school print journalist and supplement that with our video team. That said, we love it if somebody is also a photojournalist or has some video experience and can capture, it kind of depends on the piece, but whether it’s just interview footage or scenes from Tahrir Square, we’re interested in all that. This seems to be the trend in journalism with Nate Silver and Ezra Klein, everyone’s looking for people that can do data manipulation in their journalism and so are we.

Audience member: Have you figured out how to pay for it, how you want to pay for it?

Scott: What do you mean?

Audience member: Well if you’re working with one of your freelance contributors for instance and they have those kinds of abilities do you sort of do it as a lump sum or …

Scott: Yeah it varies on a case-by-case basis. One of the things that appeals to us is if we can get kind of a volume, for a package discount, we’ll pay you a little bit less than we would for just your prose and a little bit less than we would for just your video but in aggregate you’re getting more because you’re doing one-stop shopping [laughs]. It works out well for everyone.

Hasit Shah: What’s your relationship with Quartz and is there any rivalry between the two brands?

Scott: They are a sister publication in that they are under the Atlantic Media Corporation. It’s pretty wholly separate, we will sometimes, especially as they were starting out, we would share content, both directions, more that we would take occasional Quartz pieces and run them on our business site as a way of generating—it’s content for us and generating traffic for them. They have now grown into their own and the one area where they are—I mean, they are successful across the board—one area where they have sort of demonstrated to us at The Atlantic where there is growth potential is that they are very successfully generating an international audience. They consciously were devised to be mobile optimized and international and they have succeeded on both of those counts. We try to draw lessons from that. In terms of, “is there rivalry?” the short answer is no and in fact in a couple of weeks—we try to cross pollinate and share best practices across, and since they’re in New York we don’t, we do have some editorial staff there but most of our editorial staff is in Washington—but so Zach Seward who is I think deputy editor there—

Rachel: He used to work here.

Scott: Oh that’s right. So he’s going to give a presentation on what makes things go crazy viral on the Internet and so we’ll try to learn that from him. There was a brief period, I don’t know if I should say this, in the early growth phases—I mean everyone is very bullish on Quartz and I think it will be very good for the company and for The Atlantic, because if it’s starting to become very profitable that’s good for the company and good for us. I think there was a brief period when they were starting, we were sharing resources for a while, our publisher was also publisher of Quartz. I think that led to divided attention that wasn’t the most optimal way and I think that led to some hiccups, but you know Kevin Delaney and Jay Lauf who are the publisher and editor in chief of Quartz and kind of co-present there are both fantastic guys, really really driven and Kevin came from The [Wall Street] Journal.

Rachel: He was my boss actually

Scott: So you can dispute this but he’s fantastic. So no, we have a very collegial relationship with them.

Rachel Actually I have a related question to Hasit’s about expansion. The Atlantic has built a bunch of new sites and verticals: Atlantic Cities, The Wire, Atlantic Sexes. What’s the thinking in doing these verticals and how do you decide what area to …

Scott: Well that gets back to your question about experimentation. We try to grow organically at TheAtlantic.com by building up these verticals and just doing things that bring in more traffic and there are some things—so we launched The Wire, which is differentiated, and we actually recently changed it from The Atlantic Wire to The Wire. This is interesting: When we took The Atlantic out of the name, traffic plummeted, because it changed how Google ranked us. We’ve now gotten it back up to where it was but it took six months. But the idea here is that both in terms of, for consumers—what they do is very different from what TheAtlantic.com does, it’s much more quick paced, like if you want a quick take on the news. There’s not a lot of original reporting, there’s some but it gives you everything succinctly with a little bit of voice and sometimes some, not snark like Gawker, but some edge, and it’s a great way—I’ve talked to foreign journalists who say when they are trying to figure out how to do their broadcast in Colombia they’ll just read The Wire and like these are all the stories. And they’re covering the coverage too, so they’re telling you this is what The Washington Post is saying, The New York Times, this is what’s in the gossip pages. So that’s an experiment of launching a sub-brand that we think will prove to be successful. Atlantic Cities, which sort of emanated from again this sort of thinking that there is an audience of urban planners and just people who like cities. We’re trying to expand it now out of sort of wonky urban policy stuff into also lifestyle and restaurants to eat at and that kind of thing. We saw this as a kind of smart advertising play with better, different, but we’re never sure. We’re always debating, like, is this better housed as a vertical within TheAtlantic.com or should it be hived out. I can’t remember what the first one, we have Business, Politics, Global, Technology, The Sexes, Education, and a lot of it is driven by, ideally it’s driven by two things and they dovetail, the editorial interest of the editors, I mean education was one that was fairly recent. We’ve been sort of lobbying to do this, we knew our readers like stuff on education, it’s an important topic, it’s very much in our wheelhouse and we were making the case and finally our publisher was like actually we’re starting to get a lot of interest in education advertising and sure enough, and I think these things are sort of cyclical, and now all of these corporations are interested in demonstrating their interest in STEM stuff. And so that site has done very very well both in terms of traffic and in terms of monetizing it. The Sexes came out of, we’ve published enough of these things from Anne-Marie Slaughter’s to Kate Bolick’s piece to you guys’ll see on our next cover story—

Rachel: Can you say what it is?

Scott: It’s a piece by Katty Kay and Claire Shipman who are two very prominent TV journalists and it’s called “Closing the Confidence Gap,” and it’s basically, they have these fascinating findings about how, two things: one is that men have more confidence than, men have too much confidence on average, women have too little. And they sort of look into why this is, literally are there biological, hormonal neuro-scientific explanations for this or are they purely cultural? But the more interesting part is that in the workplace and this will surprise no one but it’s still fascinating to have these studies that demonstrate this, confidence matters more than competence and in fact at some point you’ll reach a point where the competence is so low and the confidence is so high that it won’t—but I think we can all think of people who, they say things with great confidence, and if you actually go back and look, they were wrong a lot of the time. But anyway they’ve marshaled all these fascinating studies to show that if people just say things with authority people will listen to them more often and they will gravitate towards them as leaders even if they’re less competent than quieter more competent people. So anyway Sexes came about that way. Another example, we launched the China Channel thinking that this would be again both a very popular site with readers and would succeed with advertisers, ultimately it didn’t generate either the traffic nor the revenue we wanted so kept it alive but we folded it into Global.

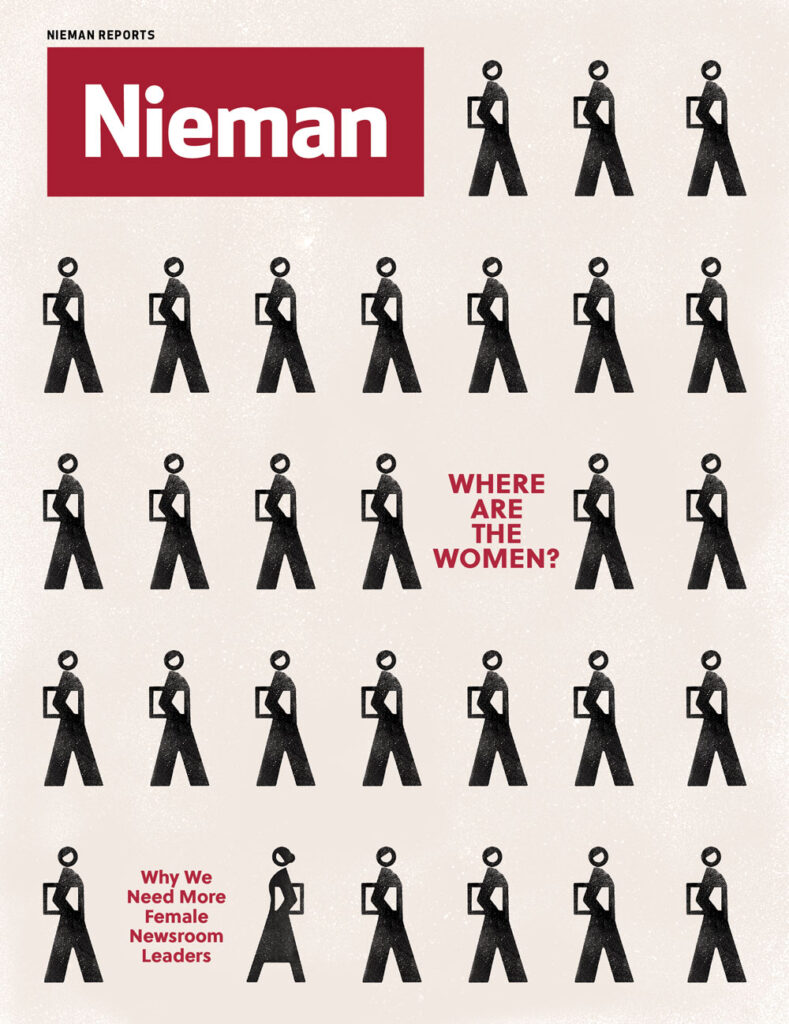

Ann Marie Lipinski: There’s been a lot of discussion in recent months about gender divide in news organizations, both on the traditional front with byline counts, and there’s another Poynter study out today that ranks public newspapers by female and male byline counts, but also on the start-up end with new digital expressions drawing largely from a male population, in some cases entirely so, in recent months. And I’m wondering if that’s something you think about as a senior manager and, in 2014, what are the roots of that?

Scott: We do think about that. I don’t have any insight into the start-ups, other than maybe techies tend to be more male, but I really don’t know anything about that personally. Every year we get dinged along with our peers, in VIDA reports about bylines. I will say when the next one comes out, we will be doing better. What I’ve tried to do, and this was never the foremost priority, but of the senior editors that I’ve hired in the last year and a half, they’re all women. In each case, I can sincerely say they were the best candidate for the job. They’ve all worked out terrifically. But, I think that doing that starts to, because we all have our networks and writers, this isn’t true across the board, but on average I think the typical female editor has somewhat more female writers in her Rolodex than the typical male editor does. And I think that having more senior female editors in the editorial management ranks has been good for us, both culturally and in terms of the product.

But the reality is, to some degree we can exert change on the world, but if you take the world as we receive it, the reality is, I’m making this number up, but it’s not crazy wrong, the number of submissions we get probably skews eight to one, male to female.

Rachel: From outside.

Scott: From outside. For every submission from a woman, we get eight from a man. Which may suggest that, my theory is that, actually Katty Kay and Claire Shipman talk about this, that men are much more willing to bloviate about things they don’t know anything about. [laughter] There’s kind of like a pundit gene or something, where they feel like they have something to say.

We have a similar issue with, which is in some ways more acute across the industry, racial diversity. We happen to have one of the best African-American journalists writing today, Ta-Nehisi Coates, but also we have three people of color in the entire organization. There’s a whole host of reasons why that is, and we have for some years done aggressive outreach to try to rectify that. But it matters not just in terms of equal opportunity and justice, but in terms of the perspective that you bring to different stories.

I don’t know if that’s a very satisfying answer, but we do think about it. It is improving, but we’re still confronted with this eight to one ratio. We can change that by actively seeking out more. If you look, I’m just thinking off the top of my head now, what was our December cover, our last two cover stories were by women. There’s also the problem of sometime, well, why are all of your female byline cover stories about women’s issues? And yes, we’re guilty of that. Again, not by design, but it tends to turn out that way. We should have more—our Pakistan story should be bylined by women.

Rachel: Or men should write the family story.

Scott: And we have done that. Stephen Marche has written actually a follow-up/rebuttal where he basically says exactly that, one of the reasons for publishing is that we do need more men writing about those kinds of issues. So, it’s a work in progress.

Rachel: What’s your readership?

Scott: I don’t know the numbers offhand. It is historically skewed more heavily male. Somewhat predictably, since we’ve published more articles of interest to women, the gap has narrowed. I never thought that made much of a difference on the business side and one time I was talking to a publisher and he was like, “You need to pick one or the other. Because when you’re going out selling to a watch company, you have to tell them are you selling men’s watches or are you selling women’s watches.” Which never occurred to me. It’s never been a principal concern of ours.

Rachel: Are there any other questions?

Audience member: So you’re one of the few people who came from The Atlantic in Boston to The Atlantic in Washington. Has being in a different city changed the way you look at stories?

Scott: It’s funny, I used to think about this a lot and it’s sort of receded now. It’s probably like the boiling frog syndrome. [laughter]

When we moved to D.C. and the headquarters there, we got a lot of criticism that “Oh you’re going to become all wonky, all “inside the Beltway,” much more narrowly focused. The reality is, partly when David Bradley bought the company, that was more his interests. Actually in the years up to when we moved, there was a continual migration in that direction, we were doing many more meat-and-potatoes public policy stories. Once we actually got to Washington, we actually made a concerted effort to expand our gambit and do much more cultural pieces, expand our literary coverage. People took the occasion of our having been based in Washington, but in fact that was the point at which we were starting to do a much broader and more diverse array.