Where Are the Women?"—last year's cover story on the decline of women in senior journalism roles—did not lack for sources. Women were overwhelmingly willing to talk candidly about their careers and frustrations and eager to wrestle publicly with questions of gender bias in our newsrooms. Typical was this observation from longtime editor and journalism school dean Geneva Overholser: "Newsrooms are allergic to cultural conversations like this, but they really are essential. Folks have to quit thinking of diversity as a wearisome duty and start understanding it as a key to success."

There was another cultural conversation we thought essential to journalism, but it has been more difficult. Talking about race and newsrooms proves complicated, even for people laboring on diversity issues. When senior editor Jan Gardner enlisted industry leaders on diversity for help identifying contributors for this issue, some said they were struggling to find journalists willing to talk openly. One cited a fear among minority journalists of damaging their relationships with their editors. Another was turned down by five journalists, some of whom were worried about job security in the face of recession layoffs that thinned the ranks of minority journalists.

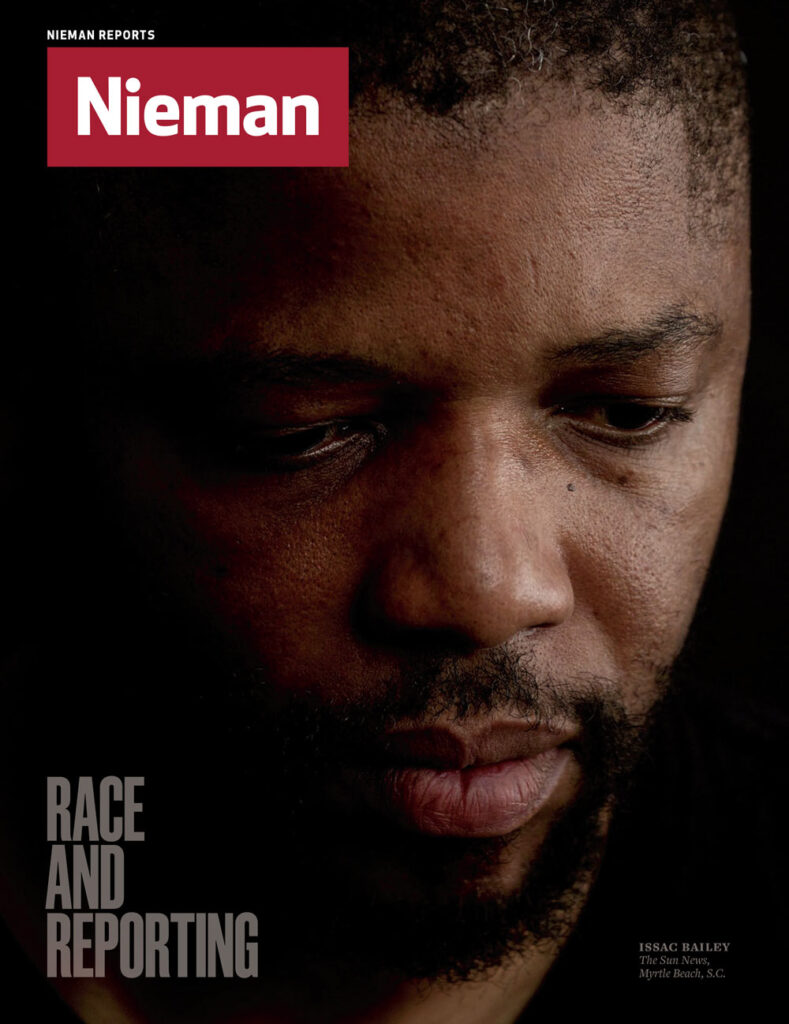

Given the perceived risks, we are especially grateful to those who wrote and spoke candidly for this issue, most importantly Issac Bailey, columnist and senior writer for The Sun News in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Issac was a 2014 Nieman Fellow and in our year together, other fellows and Nieman staff came to know him as a courageous voice on domestic social issues and a powerful narrator of his own story. Still, I was not expecting the e-mail that arrived early spring, accompanied by a brief note: “When you get time, take a look at this rough draft I’ve been working on.”

The essay I opened was a sharply observed account of a black man reporting in the age of Obama. “The shift in environment from pre- to post-Obama wasn’t subtle,” Issac wrote. “The messages I began receiving from readers went almost overnight from respectfully, if bitingly, confrontational … to overtly racist and demeaning.”

Even before Issac followed up with a request to “let me know of places that might be interested in things like this,” the answer was clear: Nieman Reports, where his essay is our cover story.

I asked Issac why many journalists, whose job is speaking truth to power, still struggle with a vocabulary for talking about race. “I’ve been thinking about this for a while now, silently frustrated, but decided to finally do it after having an uncomfortable discussion with someone I respect a great deal and realized that even that person’s view of my work in the Obama era had changed,” Issac wrote me.

Why do journalists who speak truth to power still struggle with a vocabulary for talking about race?

Issac recalled a Poynter workshop on race where Keith Woods, now NPR’s vice president for diversity, cautioned against the “failures and festivals” approach characterizing much race coverage. “On an issue as complicated and important as race, soul-searching by journalists is imperative, the kind of soul-searching an arm’s length approach simply doesn’t allow,” Issac observed. “I’m not talking about debates about affirmative action or who you eat dinner or lunch with; I’m talking about something much deeper, which is scary, and risky.”

White managers, he added, faced a different challenge. “They’ve seen what happens when a white person takes the risk to speak openly and honestly about this issue …. The response is often hostile, with little or no nuance and tends to shut conversations down. That’s one of the reasons I’ve publicly defended the likes of Bill O’Reilly, Don Imus, and Rush Limbaugh in print, not because I agree with them or think they are insightful on this issue—I don’t—but because I want there to be space for us to be able to publicly unpack this stuff together.”

Issac landed where many of the women from last year’s Nieman Reports did: eager to lead on the issue, but not alone. “For the record: I believe managers, particularly white managers, have a duty to deal with this publicly, in all its messy complexity, despite the risk. Those with the most power,” he wrote, “have the most responsibility.”