Nic Garcia’s office, like a lot of journalists’, is packed with artifacts of the craft. There’s a photo of Edward R. Murrow with a cigarette in one hand and a story in the other. Behind Garcia’s chair is a Rocky Mountain News newspaper box. And in a frame on the wall, there’s a notebook — the tall, slim kind with wire ruling at the top that used to cover newsroom desks and vanish all too fast from newspaper supply rooms. Its cover is the same shade of light blue as Air Force One, with gold letters declaring its purpose: “The Visit of President Richard M. Nixon to The People’s Republic of China.”

“Everyone who went to China with Nixon got this notebook,” Garcia says. Pan Am airlines ordered 900 of the books from Stationers Inc. of Richmond, Virginia.

Unfussy, utilitarian, ubiquitous — the reporter’s notebook carried an aura of authenticity. It’s where the raw truth mixed with the unvarnished thoughts of the journalist. The Times, NPR, and myriad other news outlets regularly run essays and analyses under the heading “reporter’s notebook.” It’s the title of a long-running documentary show in the Philippines. And, despite technological advances and dwindling numbers of journalists to use it, the notebooks are still produced, albeit for a market that may tap into nostalgia or aspiration more than reportage.

Stationers didn’t just outfit the traveling White House press corps. In 1972, the company shipped an estimated 30,000 notebooks every month to newsrooms across the country. These books had a brownish-yellow card stock cover with the word “Reporter’s” written in curly letters across the top. Below were lines for contact information, the dates of the notes within, and an address and a phone number to call to order more (Virginians were invited to call collect).

“Anybody who ordered notebooks from Stationers had a story not just about the notebooks, but about the owner, Tom Edwards,” Garcia says. “You would call to order notebooks, and you would end up spending 45 minutes on the call talking to him about journalism and about politics.”

Edwards wasn’t a journalist himself, but the company was an essential part of the trade. The distinctively shaped pads were as much a symbol of journalism as a flashbulb camera or the “press” card in a hatband. “Tom said he loved knowing the first draft of history wasn’t in the newspaper, it was in one of his notebooks,” Garcia says.

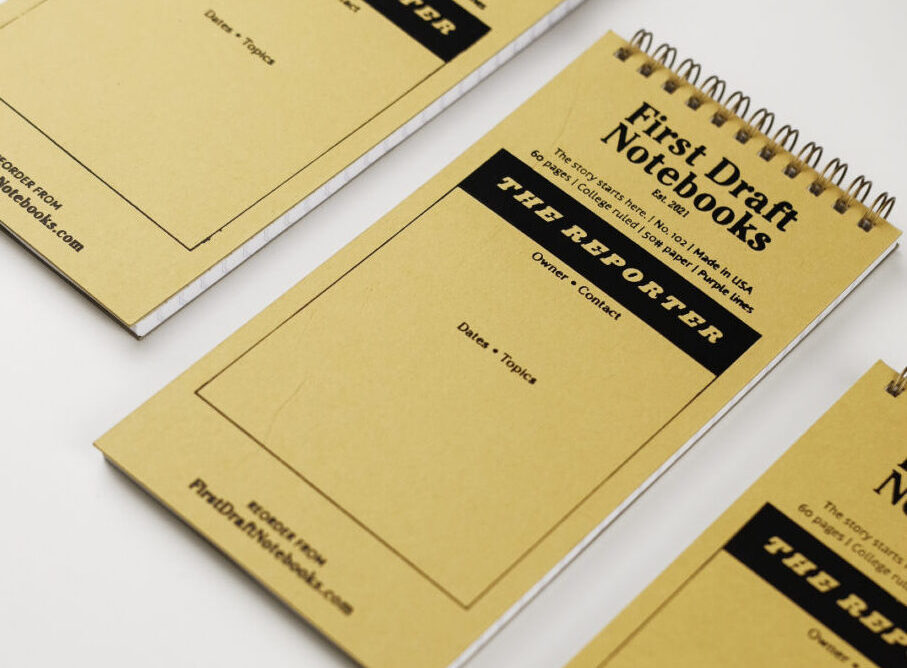

When Garcia called to restock his supply in 2021, he got bad news: Tom Edwards had passed away. Stationers was closing. The idea of shopping somewhere else was out of the question. “There are other versions of the reporters notebooks out there, but Stationers, they just had the best look and feel,” Garcia says. So he decided to make his own. Later that year, he opened for business selling notebooks with wiring at the top, thick goldenrod covers, 60 pages inside, and a name drawn from conversations he’d had with Edwards: First Draft.

Unfortunately, the notebook was becoming like fedoras and flashbulbs, a relic in the new century. Garcia closed First Draft last year, after selling about 5,000 notebooks. When interviews are done over Zoom and practically everyone in the field carries a phone that can do the job of a notebook, tape recorder, and camera, paper is less essential than ever. “Facts are facts, journalists just use fewer notebooks now,” Garcia says. And there are fewer journalists to use the notebooks. First Draft’s three years were years of record layoffs in newsrooms, constant financial instability, and declining trust in the media.

Slow sales aren’t why Garcia closed First Draft; no good reporter is in it just for the money. Garcia closed because he couldn’t keep making the notebooks. The mill that made paper for First Draft’s covers closed and Garcia couldn’t find the same color, quality, and price from another supplier in the U.S. “It didn't make sense to me if I couldn't make a product I loved,” he says. The last First Draft order went out in December. It’s the type of metaphor a reporter might jot down as they think through a story: Newspapers, and now paper itself, are in short supply.

From the spelling of “lede” to the reason for putting “-30-” to indicate the end of stories, journalism is full of traditions whose origins aren’t as well-documented as we’d like them to be before committing them to print.

One story of the notebook says Landon Edwards, Tom’s father and founder of Stationers Inc., developed it in the 1940s, modeling it after a military notebook he saw in Britain. Further south, Claude Sitton of The New York Times was known for cutting stenographer’s pads in half to make pocket-sized notebooks while covering the civil rights movement. Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff credit Sitton with the notebooks in their book “The Race Beat,” praising the pads as ideally discreet for reporting in dangerous places (Sitton reportedly never sat with his back to the door of a restaurant).

The design has other benefits — it’s narrow enough to hold in one hand and thick enough that the writer doesn’t need a desk. By the middle of the 1960s, a handful of companies made reporter’s notebooks in various sizes, but always pocketable and top-bound.

Ask a fellow journalist about the notebook and you’re likely to hear a story of how they got their first one, and how it was a rite of entry into the profession. You may also get an earful about how to properly use it. The natural inclination is to write from top to bottom, but many reporters alternate — writing top-to-bottom on the front of pages, then flipping the notebook over and writing with the wires down on the back of pages, which leads to all the writing being right-side-up when the notebook is open flat on the table next to your typewriter (or laptop). This is how Garcia uses them, and it’s how I have for years, ever since I saw a reporter I admired doing it.

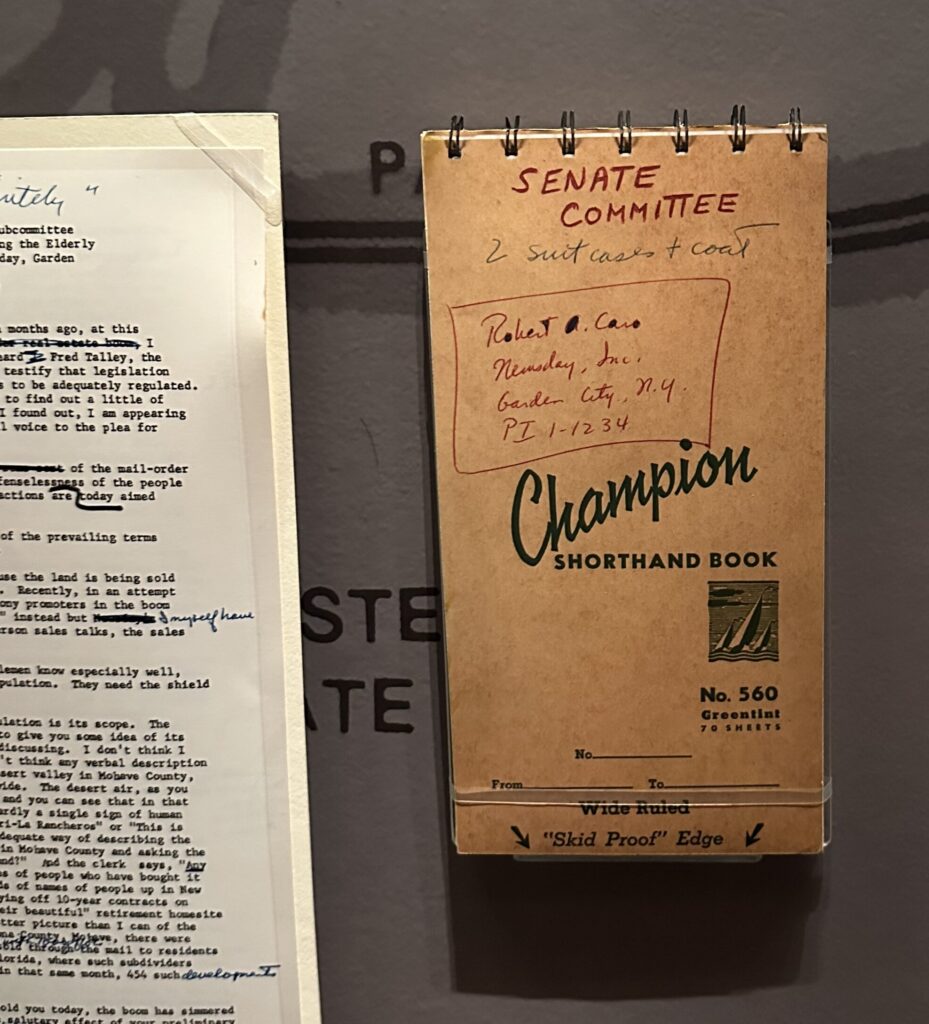

Garcia “couldn’t begin to guess” how many Stationers notebooks he’s gone through. I’ve hauled boxes of them between newsrooms, states, and continents. A stash of old, full notebooks is a measure of a career. It’s material for an unwritten memoir. Notes might be taken as evidence in court cases. On rare occasions, they end up in museums — the New York Historical Society features some of Robert Caro’s Champion-brand model 560 notebooks, which are called “shorthand books” but have the shape of the classic reporter’s model.

Someone doesn’t need to be a reporter to use a reporter’s notebook any more than they need to be a stenographer to use a steno pad or a judge to use legal paper.

“It’s just a useful size for anyone,” says Bryan Bedell, a designer with Field Notes, one of a handful of notebook companies that have become cool in the digital age. Field Notes developed its own take on a reporter’s notebook in partnership with the journalist John Dickerson. It began as a limited edition in 2015, but the company never stopped making it. Bedell doesn’t think most of the buyers are journalists, though. “Maybe there's an aspirational aspect of people who want to be journalists, or who want to look like journalists.”

Aspiration sells. The company Moleskine has long cited Hemingway in its marketing, suggesting the only thing between you and the Great American Novel is the right pad of paper. And Moleskine is just one of the higher-end brands that has moved into reporter’s notebooks (its models start around $14). There’s also a model from luxury pencil company Blackwing ($12 for two), and Baltimore-based Write Notepads ($12 each, but they have 120 pages). When most work is done on screens, a nice notebook is a luxury, or even a status symbol in meeting rooms.

“I would imagine, like most things, the market will continue towards luxury items versus bare necessity,” Bedell says.

There are lower-priced reporter’s notebooks on the market. One of the last legacy makers of the books is Portage, which began in the 1950s as the supply division for Knight Ridder newspapers and sells reporter’s notebooks for $20 a dozen. Like the newspapers Knight Ridder bought and sold, Portage has changed hands a few times. “When we took it over eight years ago, you know, reporter’s notebooks were probably half of our sales,” says Jeff Briggs, Portage’s co-owner.

Briggs says Portage still does a brisk trade in reporter’s notebooks, though he couldn’t provide specific numbers on sales. What’s changed, he says, is who buys them. It used to be that most of the sales were bulk orders to newsrooms. Now, it’s individuals buying packs online for themselves. Portage has expanded in the last few years, but not through reporter’s notebooks. The company now sells pads for specific purposes — police reports, doctors’ notes, diet tracking, and even keeping appointments for businesses. These are all increasingly electronic professions, but the notebooks sell well.

“People like paper,” Briggs says. “They like something tangible.”

The benefits of writing on paper are clear. Studies have found that taking notes by hand helps the writer remember. And no matter how ubiquitous electronic technology might be, it’s never foolproof. “I tell all of my reporters: ‘Oh my God, do not trust a recording,’” Garcia says. “At the very least, write down one good quote. Write down one good quote so you know you have that in case Apple Intelligence fails.”

Portage’s costs are lower than First Draft’s partly because of how they’re made. Even before Briggs bought the company, the notebooks were made overseas. Briggs says making them in the U.S. would mean charging four times as much, and that’s if he could find a factory to do it. ”We actually did try to move to a U.S.-based manufacturer,” he says. “They basically just want to be contract manufacturing for large companies, for example, making the private label products for CVS or Rite Aid or something like that. They're not interested in a smaller, niche brand.”

“We're really having a hard time with paper,” Bedell says. “Paper manufacturers, even going back a couple decades, have been merging into fewer and fewer bigger companies and reducing their line.”

Besides his specifications on size, look, and quality, Garcia wanted his notebooks to be both made in the U.S. and sold at a price that fit a journalist’s salary (or that wouldn’t make administrators buying supplies for newsrooms balk). “Reporters have too much to worry about than just having a crappy notebook. If you can't pay them what they deserve, at least give them a decent notebook,” he says. “I was far too altruistic in this venture, but it was important.”

Garcia sold 10-packs of the classic reporter’s notebook for $30 (a slightly shorter model costs $28 a pack). His father, a professional business coach, told him this was too low. “I said, ‘I don't plan on making a million dollars,’ and he said, ‘Well, now you never will,’” he says. “Okay. Thanks, Dad.”

Garcia considered upping his digital marketing to sell a few more notebooks, but “you have to be up on all of the trends, and frankly, I just never had the sort of time or capital to really break into making the viral videos,” he says.

The parallels just keep piling up. A need to go viral, corporate consolidation, a few large owners controlling the industry, pressure to fit into a specific form and style to ensure profits — a reporter is all too familiar with these trends, even if they don’t use a notebook anymore. But Garcia isn’t one to rely on an easy cliche. Rather than dwell on the past, he wants to learn from it. He mentions Sitton’s notebook, how it was a technological innovation that helped his reporting. “Technology has to keep advancing, and we might have reached a point where we have much better operating software to tell stories that matter,” he says. “As long as there's good journalism and we have tools to do that, that's what matters most.”