RELATED ARTICLE

"Recommended Sites"

- Christopher SimpsonNot too many years ago, I invited the chief intelligence and national security correspondent from one of America’s most prominent newspapers to a conference on news media use of remote sensing tools to cover wars and similar crises. He gruffly replied that it was all baloney (though he used a different word for it) and declined to attend. I was curious and asked him why.

“Remote sensing,” he said, “like using mind waves to read Kremlin mail,” is complete crud. (He used a different term there, as well.)

Today that correspondent tells quite a different story. He encourages his paper to use remote sensing tools such as images gathered by civilian spy satellites, especially for coverage of the World Trade Center disaster and the subsequent war in Afghanistan. Remote sensing from satellites, sometimes known as “earth observation” or as imagery gathered by spy satellites, has nothing whatever to do with ill conceived attempts to use purported psychics for intelligence collection.

Instead, unclassified imagery gathered from space has emerged as a powerful tool for capturing unique photographs and information. Properly analyzed, these images present to broad audiences some of the complex ideas that for decades have been the exclusive preserve of presidents, intelligence agencies, and a handful of scientific specialists. During the past three years alone, almost every major news organization in the world has used these tools to report on natural disasters, war, closed societies, environmental destruction, some types of human rights abuses, refugee flight and relief, scientific discoveries, agriculture and even real estate development.

The increasing popularity and effectiveness of these journalistic tools has raised concerns in some quarters that public images might reveal sensitive information in wartime, most recently in Afghanistan. Since mid-September, federal intelligence and security agencies have organized a sweeping clampdown on almost every type of geographic information available on the Internet, including civilian remote sensing information. Satellite imagery of Afghanistan, surrounding countries, and sensitive installations in the United States were among the first to go. The National Imagery and Mapping Agency—the Defense Department’s lead agency for satellite image collection and analysis—went so far as to attempt to end public distribution of decades-old, widely available Landsat 5 imagery and of topographic maps of the United States that have been commercially available in one form or another for more than 100 years. They did not succeed. Nevertheless, NIMA and other defense agencies have announced a “review” of publicly available U.S. maps in order to eliminate what they assert to be potentially dangerous information.

Procedures for suppressing what is regarded as “sensitive” imagery and geographic information have been a feature of presidential national security directives since the Reagan administration. But never before have these restrictions been implemented so rapidly or on such a wide scale. The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which operates low-resolution weather satellites, posted an image on the Internet on the afternoon of September 11 that showed a long smoke plume drifting from New York City down the east coast of the United States. Moments later, they took it off the net and issued a press statement stating that no weather imagery report at all was available for September 11. When satellite imagery watchers called NOAA on this contradiction, the agency eventually returned the satellite photograph of the smoke plume. NOAA has yet to acknowledge that they suppressed the image in the first place. Unfortunately, since mid-September NOAA’s highly regarded Operational Significant Event Imagery (OSEI) coverage of territories outside the United States has been cut to a small, anemic fraction of its former output, also without acknowledging that there has been any change.

Private satellite companies in the United States have thus far closely cooperated with the government’s effort to block media access to the large majority of current imagery. Lockheed Martin subsidiary Space Imaging Corp., located in Thorton, Colorado operates the Ikonos satellite. It captures images of the earth at about one-meter ground spatial resolution, and that is precise enough to permit experts and even ordinary readers to identify many types of military and civilian operations.

During the first week after September 11, Space Imaging released to the media high-resolution photos of Ground Zero at the collapsed trade towers in Manhattan and at the Pentagon. The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, scores of major publications, and every major television news organization in the world employed these dramatic photographs to analyze, document and explain what had taken place during the attacks. Meanwhile, SPOT Image, a French satellite company with a significant share of the U.S. market (www.spot.com), provided somewhat similar 15-meter resolution “images of infamy” it had gathered from more than 400 miles in space.

As dramatic as those photos are, they have since become something of a fig leaf that has obscured more recent, sweeping restrictions on news media use of satellite imaging. Beginning at least as early as October, the Department of Defense (DOD) has moved aggressively to shut down media access to overhead images of the heavy bombing of Afghanistan, except for photos that the DOD presents at its own news conferences. In the process, the DOD appears to have sidestepped its own regulations, some legal experts say, and might have broken the law.

The present controversy about public access to satellite imagery began a bit less than a decade ago when the U.S. government drafted elaborate regulations claiming it had the authority to exercise “shutter control” over U.S.-licensed satellites. Executive agencies authorized a procedure they would use to shut down collection of otherwise available imagery when key members of the President’s cabinet agreed that national security, foreign policy, or similar matters might be endangered. Critics contended that the “shutter control” procedures amounted to governmental prior restraint on publishing, a type of censorship that the Supreme Court has long held to be unconstitutional in almost every circumstance.

The Radio-Television News Directors Association said that the first time the procedure was actually used they would challenge its constitutionality in court. Similar objections came from a number of news and publishing organizations and some representatives of the civilian satellite companies themselves. But until October 2001, no clearcut test cases had arisen. Then, as the United States began its bombing campaign in Afghanistan, the DOD signed contracts with Space Imaging to purchase exclusive rights to all of the company’s imagery collected anywhere near Afghanistan.

These tactics, known as “preclusive buying,” have been a feature of U.S. economic warfare since at least World War I. Earlier preclusive buying efforts sought to choke off shipments of tungsten and other strategic minerals to Nazi Germany, for example. This time, though, the object has been to shut down U.S. news media access to information about the war in Afghanistan, the flight of refugees, and the widening crisis in West Asia.

Today, the Defense Department and Space Imaging contend that this preclusive buying is a simple contract matter. “This was a solid business transaction that brought great value to the [U.S.] government,” said the company’s Washington representative, Mark Brender. “Nothing more; nothing less.” But critics contend that the Department of Defense has used the contracts as a device to avoid their own regulations and thus sidestep the legal challenge that would almost certainly follow. “This contract is a way of disguised censorship aimed at preventing the media from doing their monitoring job,” contended Reporters sans Frontières (Reporters Without Borders) executive director Robert Menard. The Guardian (U.K.) characterized the deal as “spending millions of dollars to prevent Western media from seeing pictures of the effects of bombing in Afghanistan.” Ernest Miller, writing in Yale University’s LawMeme electronic newsletter, concluded that preclusive buying should be understood as “shutter control by means other than those enumerated in the current regulations,” that has added new regulatory and constitutional law issues to the existing controversy over the regulations themselves.

Perhaps most disturbingly, Guardian correspondent Duncan Campbell reported that the decision to buy rights to all satellite imagery appears to have been made on October 10, then backdated by a week or more. The date is significant, he contended, because the agreement took place soon after news organizations attempted to purchase high-resolution images of Daruta, Afghanistan, to follow up on reports that bombing raids had killed a large number of civilians at that settlement. (The DOD has stated that the raids at Daruta hit nearby Taliban training camps. The dispute over the civilian deaths has yet to be resolved.)

Meanwhile, Spot Image has also declined to make the most of its current take of imagery available to news organizations. Industry insiders contend that all Spot imagery of Western Asia gathered since September 11 has gone to the French government, where it is said to facilitate French horse-trading of intelligence concerning terrorism with U.S. intelligence agencies. For the moment, at least, the ostensibly civilian Spot satellites are operating in tandem with France’s military Helios spy satellites, which have a very similar design to Spot’s birds and use much of the same command and control infrastructure.

Neither Space Imaging nor Spot have been willing to say much to the news media. There have been some interesting exceptions, however. At SpaceImaging, the company thus far has made public only one before-and-after image collected over Afghanistan. It illustrates a precision airstrike that effectively destroyed an Afghan airfield near Kandahar without damaging nearby homes. The images and the analysis that accompanied them were presented to news organizations as the product of an independent information company. In reality, the released image was calculated to be a “big wet kiss,” as a satellite industry insider put it, for the U.S. war effort. (It was also cleared by the DOD prior to release.)

For the moment, the only source of current, civilian, high-resolution imagery from Afghanistan appears to be a remarkable corporate hybrid whose lineage exemplifies the world of post-cold war intelligence. ImageSat International—formerly known as West Indian Space Inc.—is a partnership of the state-owned Israeli Aircraft Industries (IAI), a U.S. software company, and a second major Israeli defense contractor. The company operates out of Cyprus and from tax havens in the Caribbean and launches its birds from Siberia aboard leased Russian rockets. The 2.5-meter to three-meter resolution Eros 1-A satellite is officially a civilian “earth resources observation” tool. A closer look reveals this remote sensing satellite is designed to specs closely modeled on Israel’s highly secret Ofeq-3 spy satellites, which are also built by IAI. The new company sells imagery worldwide about two weeks after it is gathered at www.westindianspace.com or www.imagesatintl.com.

Controversy still erupts from time to time over interpretation of some imagery, or over these satellites’ potential threat to national security or personal privacy. But so far, at least, no serious abuses of these tools by media organizations have come to light. When high-quality imagery has been publicly available, disagreements over its interpretation have proven to be high-tech versions of healthy, democratic discussion in which society’s best approximation of truth emerges through a clash of ideas. The Institute for Science and International Security’s recent book, “Solving the North Korean Nuclear Puzzle,” provides an example. Imagery and information concerning North Korea’s missile and nuclear weapons programs is quite sensitive by any measure. Nevertheless, the informed public analysis and debate about Korea that has been spurred by imagery from civilian remote sensing satellites has led to more effective monitoring of arms limitation agreements and—at least so far—more effective means to cope with the arms race in Asia.

Today’s battle over access to current, accurate satellite imagery from Afghanistan is new in many ways, of course. Yet in a certain sense it remains similar to public debates over earlier newsgathering technologies in wartime such as television, radio and—not really so long ago—the telegraph. Media organizations have long preferred to attribute positive effects of open information to their responsible handling of news. The armed forces, on the other hand, have often traced that result at least in part to military efforts to shut down unwanted news reports before they begin.

It seems clear that spy satellite tools—regarded by some as neutral news sources—have already adapted quite easily to modern public relations. And, like it or not, the fact that today’s debate about war coverage focuses on information collected by satellites is a sure sign that this new information tool has come of age.

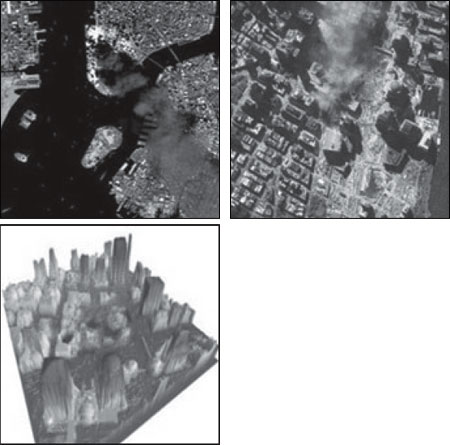

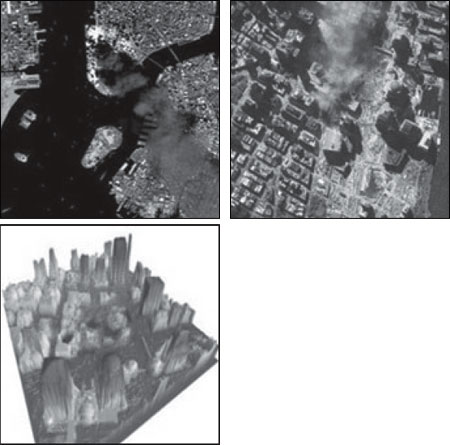

Imagery for news and analysis: At top left, a Spot Image satellite photo of Ground Zero captured on September 11, less than three hours after the towers’ collapse. The thermal infrared band identifies fierce fires (in white in this picture) at the base of the smoke plumes. Ground spatial resolution of the image—that is, the size of an object represented by a single pixel—is about 15 meters. At top right, a one-meter resolution Ikonos satellite image of the same area taken on September 15. Debris and emergency vehicles are clearly visible. This image was collected by an observation satellite some 423 miles in space traveling at about 17,500 mph. At bottom, this LIDAR image extrusion prepared by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) permits precise three-dimensional location of elevator shafts, stairwells and broken support structures at the destroyed World Trade Center. When merged with other satellite data, the final color 3-D image provides approximately 30 meter resolution. Image credits: (top left) Spot Image/CNES, (top right) Space Imaging, (bottom) NOAA.

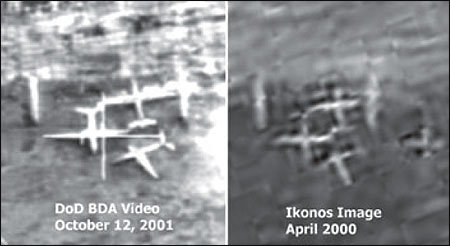

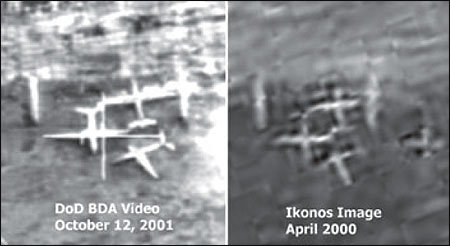

Imagery and Public Relations: At left, a gun camera video image of what appears to be a highly effective air strike on military jets at Kabul airport. The image received heavy television coverage when it was released by the Department of Defense shortly after the beginning of the air war in Afghanistan. At right, an Ikonos satellite image showing that the same planes were in precisely the same position 18 months earlier, demonstrating that the targets were actually "three derelict cargo airplanes," writes analyst Tim Brown of GlobalSecurity.org, who discovered the archive image. U.S. air strikes on these targets during the first 72 hours of the air war had little military value, he contends, except for the "strong media and visual impact" produced by network news coverage of the vivid imagery. Image credits: (left) Department of Defense, (right) Space Imaging / GlobalSecurity.org.

Christopher Simpson specializes in national security and media literacy issues at the School of Communication at American University in Washington, D.C. He directs the school’s project on Satellite Imagery and the News Media. Simpson spent more than 15 years as a journalist and is author or editor of six books on communication, national security, and human rights.

"Recommended Sites"

- Christopher SimpsonNot too many years ago, I invited the chief intelligence and national security correspondent from one of America’s most prominent newspapers to a conference on news media use of remote sensing tools to cover wars and similar crises. He gruffly replied that it was all baloney (though he used a different word for it) and declined to attend. I was curious and asked him why.

“Remote sensing,” he said, “like using mind waves to read Kremlin mail,” is complete crud. (He used a different term there, as well.)

Today that correspondent tells quite a different story. He encourages his paper to use remote sensing tools such as images gathered by civilian spy satellites, especially for coverage of the World Trade Center disaster and the subsequent war in Afghanistan. Remote sensing from satellites, sometimes known as “earth observation” or as imagery gathered by spy satellites, has nothing whatever to do with ill conceived attempts to use purported psychics for intelligence collection.

Instead, unclassified imagery gathered from space has emerged as a powerful tool for capturing unique photographs and information. Properly analyzed, these images present to broad audiences some of the complex ideas that for decades have been the exclusive preserve of presidents, intelligence agencies, and a handful of scientific specialists. During the past three years alone, almost every major news organization in the world has used these tools to report on natural disasters, war, closed societies, environmental destruction, some types of human rights abuses, refugee flight and relief, scientific discoveries, agriculture and even real estate development.

The increasing popularity and effectiveness of these journalistic tools has raised concerns in some quarters that public images might reveal sensitive information in wartime, most recently in Afghanistan. Since mid-September, federal intelligence and security agencies have organized a sweeping clampdown on almost every type of geographic information available on the Internet, including civilian remote sensing information. Satellite imagery of Afghanistan, surrounding countries, and sensitive installations in the United States were among the first to go. The National Imagery and Mapping Agency—the Defense Department’s lead agency for satellite image collection and analysis—went so far as to attempt to end public distribution of decades-old, widely available Landsat 5 imagery and of topographic maps of the United States that have been commercially available in one form or another for more than 100 years. They did not succeed. Nevertheless, NIMA and other defense agencies have announced a “review” of publicly available U.S. maps in order to eliminate what they assert to be potentially dangerous information.

Procedures for suppressing what is regarded as “sensitive” imagery and geographic information have been a feature of presidential national security directives since the Reagan administration. But never before have these restrictions been implemented so rapidly or on such a wide scale. The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which operates low-resolution weather satellites, posted an image on the Internet on the afternoon of September 11 that showed a long smoke plume drifting from New York City down the east coast of the United States. Moments later, they took it off the net and issued a press statement stating that no weather imagery report at all was available for September 11. When satellite imagery watchers called NOAA on this contradiction, the agency eventually returned the satellite photograph of the smoke plume. NOAA has yet to acknowledge that they suppressed the image in the first place. Unfortunately, since mid-September NOAA’s highly regarded Operational Significant Event Imagery (OSEI) coverage of territories outside the United States has been cut to a small, anemic fraction of its former output, also without acknowledging that there has been any change.

Private satellite companies in the United States have thus far closely cooperated with the government’s effort to block media access to the large majority of current imagery. Lockheed Martin subsidiary Space Imaging Corp., located in Thorton, Colorado operates the Ikonos satellite. It captures images of the earth at about one-meter ground spatial resolution, and that is precise enough to permit experts and even ordinary readers to identify many types of military and civilian operations.

During the first week after September 11, Space Imaging released to the media high-resolution photos of Ground Zero at the collapsed trade towers in Manhattan and at the Pentagon. The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, scores of major publications, and every major television news organization in the world employed these dramatic photographs to analyze, document and explain what had taken place during the attacks. Meanwhile, SPOT Image, a French satellite company with a significant share of the U.S. market (www.spot.com), provided somewhat similar 15-meter resolution “images of infamy” it had gathered from more than 400 miles in space.

As dramatic as those photos are, they have since become something of a fig leaf that has obscured more recent, sweeping restrictions on news media use of satellite imaging. Beginning at least as early as October, the Department of Defense (DOD) has moved aggressively to shut down media access to overhead images of the heavy bombing of Afghanistan, except for photos that the DOD presents at its own news conferences. In the process, the DOD appears to have sidestepped its own regulations, some legal experts say, and might have broken the law.

The present controversy about public access to satellite imagery began a bit less than a decade ago when the U.S. government drafted elaborate regulations claiming it had the authority to exercise “shutter control” over U.S.-licensed satellites. Executive agencies authorized a procedure they would use to shut down collection of otherwise available imagery when key members of the President’s cabinet agreed that national security, foreign policy, or similar matters might be endangered. Critics contended that the “shutter control” procedures amounted to governmental prior restraint on publishing, a type of censorship that the Supreme Court has long held to be unconstitutional in almost every circumstance.

The Radio-Television News Directors Association said that the first time the procedure was actually used they would challenge its constitutionality in court. Similar objections came from a number of news and publishing organizations and some representatives of the civilian satellite companies themselves. But until October 2001, no clearcut test cases had arisen. Then, as the United States began its bombing campaign in Afghanistan, the DOD signed contracts with Space Imaging to purchase exclusive rights to all of the company’s imagery collected anywhere near Afghanistan.

These tactics, known as “preclusive buying,” have been a feature of U.S. economic warfare since at least World War I. Earlier preclusive buying efforts sought to choke off shipments of tungsten and other strategic minerals to Nazi Germany, for example. This time, though, the object has been to shut down U.S. news media access to information about the war in Afghanistan, the flight of refugees, and the widening crisis in West Asia.

Today, the Defense Department and Space Imaging contend that this preclusive buying is a simple contract matter. “This was a solid business transaction that brought great value to the [U.S.] government,” said the company’s Washington representative, Mark Brender. “Nothing more; nothing less.” But critics contend that the Department of Defense has used the contracts as a device to avoid their own regulations and thus sidestep the legal challenge that would almost certainly follow. “This contract is a way of disguised censorship aimed at preventing the media from doing their monitoring job,” contended Reporters sans Frontières (Reporters Without Borders) executive director Robert Menard. The Guardian (U.K.) characterized the deal as “spending millions of dollars to prevent Western media from seeing pictures of the effects of bombing in Afghanistan.” Ernest Miller, writing in Yale University’s LawMeme electronic newsletter, concluded that preclusive buying should be understood as “shutter control by means other than those enumerated in the current regulations,” that has added new regulatory and constitutional law issues to the existing controversy over the regulations themselves.

Perhaps most disturbingly, Guardian correspondent Duncan Campbell reported that the decision to buy rights to all satellite imagery appears to have been made on October 10, then backdated by a week or more. The date is significant, he contended, because the agreement took place soon after news organizations attempted to purchase high-resolution images of Daruta, Afghanistan, to follow up on reports that bombing raids had killed a large number of civilians at that settlement. (The DOD has stated that the raids at Daruta hit nearby Taliban training camps. The dispute over the civilian deaths has yet to be resolved.)

Meanwhile, Spot Image has also declined to make the most of its current take of imagery available to news organizations. Industry insiders contend that all Spot imagery of Western Asia gathered since September 11 has gone to the French government, where it is said to facilitate French horse-trading of intelligence concerning terrorism with U.S. intelligence agencies. For the moment, at least, the ostensibly civilian Spot satellites are operating in tandem with France’s military Helios spy satellites, which have a very similar design to Spot’s birds and use much of the same command and control infrastructure.

Neither Space Imaging nor Spot have been willing to say much to the news media. There have been some interesting exceptions, however. At SpaceImaging, the company thus far has made public only one before-and-after image collected over Afghanistan. It illustrates a precision airstrike that effectively destroyed an Afghan airfield near Kandahar without damaging nearby homes. The images and the analysis that accompanied them were presented to news organizations as the product of an independent information company. In reality, the released image was calculated to be a “big wet kiss,” as a satellite industry insider put it, for the U.S. war effort. (It was also cleared by the DOD prior to release.)

For the moment, the only source of current, civilian, high-resolution imagery from Afghanistan appears to be a remarkable corporate hybrid whose lineage exemplifies the world of post-cold war intelligence. ImageSat International—formerly known as West Indian Space Inc.—is a partnership of the state-owned Israeli Aircraft Industries (IAI), a U.S. software company, and a second major Israeli defense contractor. The company operates out of Cyprus and from tax havens in the Caribbean and launches its birds from Siberia aboard leased Russian rockets. The 2.5-meter to three-meter resolution Eros 1-A satellite is officially a civilian “earth resources observation” tool. A closer look reveals this remote sensing satellite is designed to specs closely modeled on Israel’s highly secret Ofeq-3 spy satellites, which are also built by IAI. The new company sells imagery worldwide about two weeks after it is gathered at www.westindianspace.com or www.imagesatintl.com.

Controversy still erupts from time to time over interpretation of some imagery, or over these satellites’ potential threat to national security or personal privacy. But so far, at least, no serious abuses of these tools by media organizations have come to light. When high-quality imagery has been publicly available, disagreements over its interpretation have proven to be high-tech versions of healthy, democratic discussion in which society’s best approximation of truth emerges through a clash of ideas. The Institute for Science and International Security’s recent book, “Solving the North Korean Nuclear Puzzle,” provides an example. Imagery and information concerning North Korea’s missile and nuclear weapons programs is quite sensitive by any measure. Nevertheless, the informed public analysis and debate about Korea that has been spurred by imagery from civilian remote sensing satellites has led to more effective monitoring of arms limitation agreements and—at least so far—more effective means to cope with the arms race in Asia.

Today’s battle over access to current, accurate satellite imagery from Afghanistan is new in many ways, of course. Yet in a certain sense it remains similar to public debates over earlier newsgathering technologies in wartime such as television, radio and—not really so long ago—the telegraph. Media organizations have long preferred to attribute positive effects of open information to their responsible handling of news. The armed forces, on the other hand, have often traced that result at least in part to military efforts to shut down unwanted news reports before they begin.

It seems clear that spy satellite tools—regarded by some as neutral news sources—have already adapted quite easily to modern public relations. And, like it or not, the fact that today’s debate about war coverage focuses on information collected by satellites is a sure sign that this new information tool has come of age.

Imagery for news and analysis: At top left, a Spot Image satellite photo of Ground Zero captured on September 11, less than three hours after the towers’ collapse. The thermal infrared band identifies fierce fires (in white in this picture) at the base of the smoke plumes. Ground spatial resolution of the image—that is, the size of an object represented by a single pixel—is about 15 meters. At top right, a one-meter resolution Ikonos satellite image of the same area taken on September 15. Debris and emergency vehicles are clearly visible. This image was collected by an observation satellite some 423 miles in space traveling at about 17,500 mph. At bottom, this LIDAR image extrusion prepared by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) permits precise three-dimensional location of elevator shafts, stairwells and broken support structures at the destroyed World Trade Center. When merged with other satellite data, the final color 3-D image provides approximately 30 meter resolution. Image credits: (top left) Spot Image/CNES, (top right) Space Imaging, (bottom) NOAA.

Imagery and Public Relations: At left, a gun camera video image of what appears to be a highly effective air strike on military jets at Kabul airport. The image received heavy television coverage when it was released by the Department of Defense shortly after the beginning of the air war in Afghanistan. At right, an Ikonos satellite image showing that the same planes were in precisely the same position 18 months earlier, demonstrating that the targets were actually "three derelict cargo airplanes," writes analyst Tim Brown of GlobalSecurity.org, who discovered the archive image. U.S. air strikes on these targets during the first 72 hours of the air war had little military value, he contends, except for the "strong media and visual impact" produced by network news coverage of the vivid imagery. Image credits: (left) Department of Defense, (right) Space Imaging / GlobalSecurity.org.

Christopher Simpson specializes in national security and media literacy issues at the School of Communication at American University in Washington, D.C. He directs the school’s project on Satellite Imagery and the News Media. Simpson spent more than 15 years as a journalist and is author or editor of six books on communication, national security, and human rights.