Let’s take a brief look at the problem with political reporting.

First, I read a story by the Associated Press explaining why the Democratic brand is “toxic” in many largely white rural areas in the United States. It included several incidents of Republicans intimidating their Democratic neighbors into silence but was written as a concerning development for Democratic political fortunes during the midterms, not as though such acts of intimidation are disturbing in a democracy. That story also gave no hint of critical context that the party in power almost always loses a significant number of seats during the midterms — no matter how unified or divided they seem, no matter gas prices, no matter what the final jobs report before the election reveals.

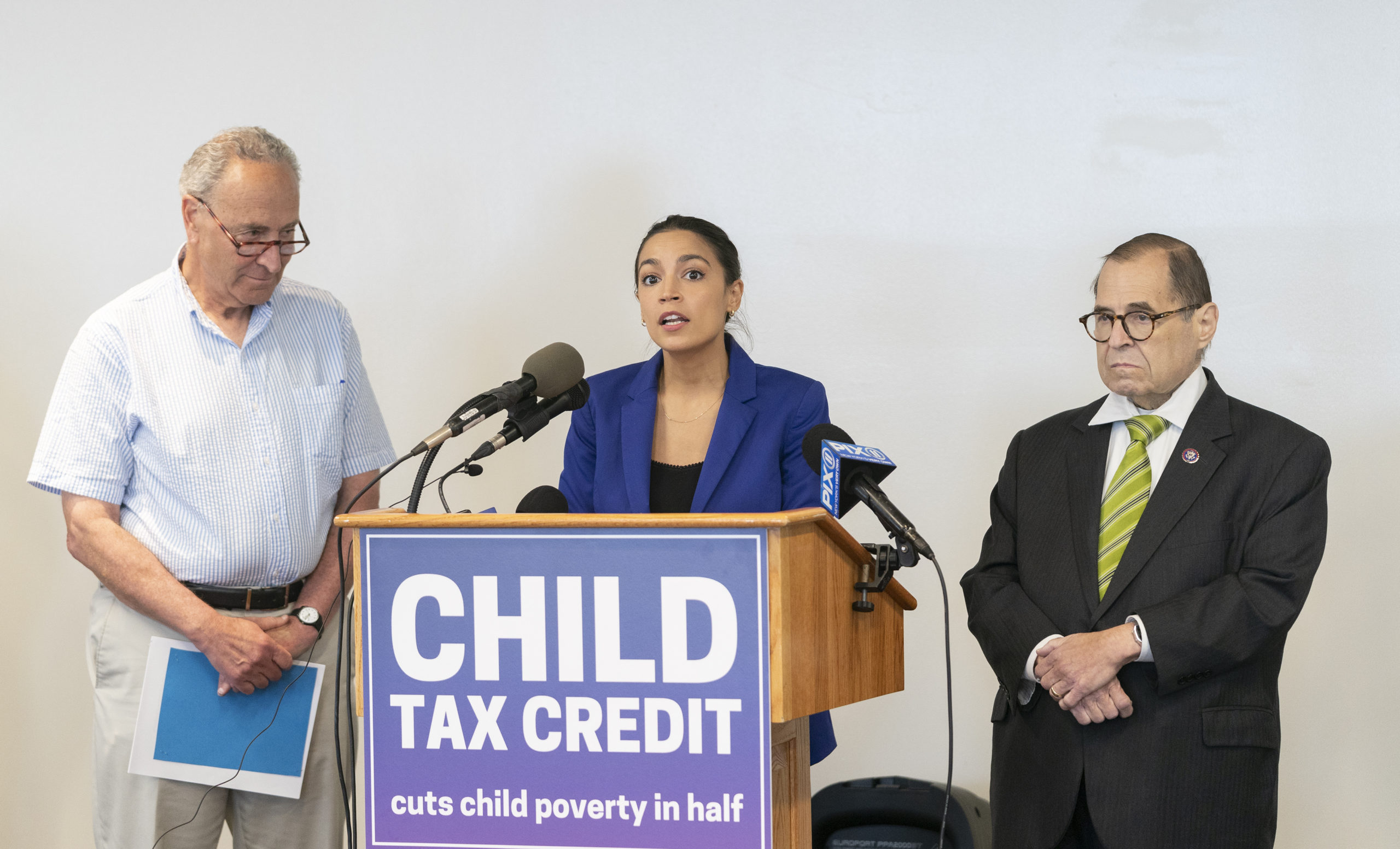

Then, I read an Axios report declaring that the recall of three school board members in San Francisco meant “the hard-left politics” of the so-called Squad “is backfiring big-time on the party in power,” as though Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was responsible for the mismanagement of school closings due to Covid-19 from 3,000 miles away.

That came on the heels of a piece by Washington Post reporter Philip Bump that tried to defend the media’s intense focus on Hillary Clinton’s private server compared to coverage of news that Donald Trump routinely destroyed documents and took 15 boxes of classified materials upon his exit from the White House. Bump spends 17 paragraphs justifying the coverage of Clinton before dismissing the lack of coverage of Trump as a function of reporters only having one week with the story, neglecting to mention the editorial decisions that kept one story on the front page for months while the other has been buried deep in the double-digit page count of the A section.

In between those stories, I came across this report from the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University: “3.7 million more children in poverty in Jan 2022 without monthly Child Tax Credit.”

Almost 4 million poor children were thrust back into poverty nearly overnight because of the political decisions of our elected leaders. But those reading the Axios piece about top Democrats lamenting the influence of The Squad would have had to look elsewhere to know that it was The Squad, among other “far-left” Democrats, who had pushed through a policy earlier in 2021 that had raised nearly 4 million kids out of poverty. The piece could have mentioned how supposedly “far-left” policies affected everyday Americans even if they don’t make life easier for Democrats at the polls.

Similarly, those reading the Associated Press story about the Democratic brand being “toxic” in rural America would have had to look elsewhere for the knowledge that rural Americans have been among the primary beneficiaries of policies advocated by The Squad and opposed by “moderates” such as Joe Manchin — who reportedly believes the extended child tax credit could lead to government dependence, or worse — and nearly every Republican in Congress. But they would know well that political operatives believe chants of “defund the police” are supposedly the reason rural white-working class voters have been flocking to the Republican Party.

There’s little to no nuance, just seemingly clear-headed analysis about the political fortunes of one of America’s two major political parties. This kind of framing has been repeated for years. Many political pundits and reporters wrote or spoke about “Obamacare” primarily through the horse-race lens, often neglecting to explain to Americans that the policy was literally saving and improving countless lives every year.

Far too often, the effect a policy has on everyday Americans takes a backseat in our reporting, even when the policy does great good for the most vulnerable among us. And I’ve seen it take hold in our coverage of threats to our democracy. We seem afraid of clearly telling our audiences that our democracy might be in real trouble and who is largely responsible for that. Instead, we equate anti-democratic threats that burst into the open on Jan. 6, 2021 and have metastasized since with efforts to defend democracy against them.

Though we don’t like admitting as much, our coverage decisions affect electoral outcomes and are affected by what we expect to happen, creating a kind of circular reasoning that keeps us trapped in a horse-race mindset that blinds us to more complex, more important realities. For a variety of reasons — aggressive voter restriction efforts and the shame they feel for needing government “handouts” among them — many of the most vulnerable among us don’t vote often, if at all. That’s why political strategists and others trying to cobble together governing coalitions aren’t likely to elevate their voices.

Still, policies such as the extended child tax credit help immensely when they are signed into law, and it hurts just as much when those policies are allowed to expire. These citizens don’t burn up their representatives’ phone lines, don’t write letters to the editor, don’t place political signs in their front yards. They suffer in silence as politicians — and reporters — flock to those most likely to show up at the polls or a political rally or social justice protest. And it shows in our coverage.

Nearly four million children were thrust back into poverty essentially overnight. A policy that showed immediate promise and effectiveness — a policy championed by The Squad — was allowed to vanish. A policy that likely helped lower the opioid death rate. We noted it and moved on. We focused our attention on the fates of little-known politicians on a school board in San Francisco while millions of poor children have a literal lifeline yanked away — because they won’t make the difference in whether Democrats hold onto power nine months from now or Republicans retake Congress.

First, I read a story by the Associated Press explaining why the Democratic brand is “toxic” in many largely white rural areas in the United States. It included several incidents of Republicans intimidating their Democratic neighbors into silence but was written as a concerning development for Democratic political fortunes during the midterms, not as though such acts of intimidation are disturbing in a democracy. That story also gave no hint of critical context that the party in power almost always loses a significant number of seats during the midterms — no matter how unified or divided they seem, no matter gas prices, no matter what the final jobs report before the election reveals.

Then, I read an Axios report declaring that the recall of three school board members in San Francisco meant “the hard-left politics” of the so-called Squad “is backfiring big-time on the party in power,” as though Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was responsible for the mismanagement of school closings due to Covid-19 from 3,000 miles away.

That came on the heels of a piece by Washington Post reporter Philip Bump that tried to defend the media’s intense focus on Hillary Clinton’s private server compared to coverage of news that Donald Trump routinely destroyed documents and took 15 boxes of classified materials upon his exit from the White House. Bump spends 17 paragraphs justifying the coverage of Clinton before dismissing the lack of coverage of Trump as a function of reporters only having one week with the story, neglecting to mention the editorial decisions that kept one story on the front page for months while the other has been buried deep in the double-digit page count of the A section.

In between those stories, I came across this report from the Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University: “3.7 million more children in poverty in Jan 2022 without monthly Child Tax Credit.”

Almost 4 million poor children were thrust back into poverty nearly overnight because of the political decisions of our elected leaders. But those reading the Axios piece about top Democrats lamenting the influence of The Squad would have had to look elsewhere to know that it was The Squad, among other “far-left” Democrats, who had pushed through a policy earlier in 2021 that had raised nearly 4 million kids out of poverty. The piece could have mentioned how supposedly “far-left” policies affected everyday Americans even if they don’t make life easier for Democrats at the polls.

Similarly, those reading the Associated Press story about the Democratic brand being “toxic” in rural America would have had to look elsewhere for the knowledge that rural Americans have been among the primary beneficiaries of policies advocated by The Squad and opposed by “moderates” such as Joe Manchin — who reportedly believes the extended child tax credit could lead to government dependence, or worse — and nearly every Republican in Congress. But they would know well that political operatives believe chants of “defund the police” are supposedly the reason rural white-working class voters have been flocking to the Republican Party.

There’s little to no nuance, just seemingly clear-headed analysis about the political fortunes of one of America’s two major political parties. This kind of framing has been repeated for years. Many political pundits and reporters wrote or spoke about “Obamacare” primarily through the horse-race lens, often neglecting to explain to Americans that the policy was literally saving and improving countless lives every year.

Far too often, the effect a policy has on everyday Americans takes a backseat in our reporting, even when the policy does great good for the most vulnerable among us. And I’ve seen it take hold in our coverage of threats to our democracy. We seem afraid of clearly telling our audiences that our democracy might be in real trouble and who is largely responsible for that. Instead, we equate anti-democratic threats that burst into the open on Jan. 6, 2021 and have metastasized since with efforts to defend democracy against them.

Though we don’t like admitting as much, our coverage decisions affect electoral outcomes and are affected by what we expect to happen, creating a kind of circular reasoning that keeps us trapped in a horse-race mindset that blinds us to more complex, more important realities. For a variety of reasons — aggressive voter restriction efforts and the shame they feel for needing government “handouts” among them — many of the most vulnerable among us don’t vote often, if at all. That’s why political strategists and others trying to cobble together governing coalitions aren’t likely to elevate their voices.

Still, policies such as the extended child tax credit help immensely when they are signed into law, and it hurts just as much when those policies are allowed to expire. These citizens don’t burn up their representatives’ phone lines, don’t write letters to the editor, don’t place political signs in their front yards. They suffer in silence as politicians — and reporters — flock to those most likely to show up at the polls or a political rally or social justice protest. And it shows in our coverage.

Nearly four million children were thrust back into poverty essentially overnight. A policy that showed immediate promise and effectiveness — a policy championed by The Squad — was allowed to vanish. A policy that likely helped lower the opioid death rate. We noted it and moved on. We focused our attention on the fates of little-known politicians on a school board in San Francisco while millions of poor children have a literal lifeline yanked away — because they won’t make the difference in whether Democrats hold onto power nine months from now or Republicans retake Congress.